The process of filtering cellulose fibers—found in plant cells, most often today from wood— suspended in water (pulp), which are then formed into sheets and dried (paper).

Lightweight, flexible, sturdy, and inexpensive, paper is one of the most important inventions of human civilization, although the perceived environmental impacts of its industrialized production have drawn criticism in recent decades.

The invention of paper lagged far behind the invention of writing. Sumerians created the first writing system in the fourth millennium B.C.E.; known as cuneiform, it consists of the marks of a wedge-shaped stylus pressed into a clay tablet. Egyptians used various character sets on papyrus and stone in the following millennia, while ancient Greeks and Hebrews used wax-covered stone and wooden tablets. Writing in China dates to the second millennium B.C.E., when bamboo strips and woven silk were used. But by the second or first centuries B.C.E., papermaking—using a process that, in its fundamentals, has little changed in 2,000 years—was well known there. The first Chinese paper was made of bark and refuse hemp and linen rags mixed into a watery slurry and allowed to dry in sheets.

From China, paper also spread eastward to Korea through trade and other cultural contact, likely by the third century, and then to Japan, perhaps by the fourth century. Papermakers in China gradually reduced or eliminated their use of refuse cloth and turned almost exclusively to raw natural fibers, such as hemp, rattan, bamboo, and mulberry. Paper also spread westward along trade routes, and, by the eighth century, it reached central Asia, where Muslim papermakers developed techniques utilizing refuse rag fibers. Trade and conquest by Muslims are alone responsible for the introduction of paper to Europe by the eleventh century, first in Islamic Spain. Indeed, the word for today’s standard unit of paper—”ream”—is derived from the Spanish resma, which in turn comes from the Arabic rizma (bundle), the primary form in which paper was traded throughout Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Italy was also an early adopter of papermaking techniques acquired through cultural and political ties with Arab-Islamic northern Africa: paper first appeared in Sicily before the twelfth century.

Europeans were slow to abandon their use of parchment—animal skins prepared for writing on—and papyrus, but Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of movable type in the fifteenth century made demand for paper explode. The print run of his Bible, the first ever printed, is revealing: it is believed to have included 35 copies on parchment and 165 on paper. As papermaking spread northward, pulp and paper production in Europe became dominated by mills making paper that, unlike Chinese paper made for brushes, could withstand the physical stresses of mechanized printing. By the early seventeenth century, Antwerp and Cologne had become major centers for the international trade in paper, with Amsterdam soon to rise to similar importance.

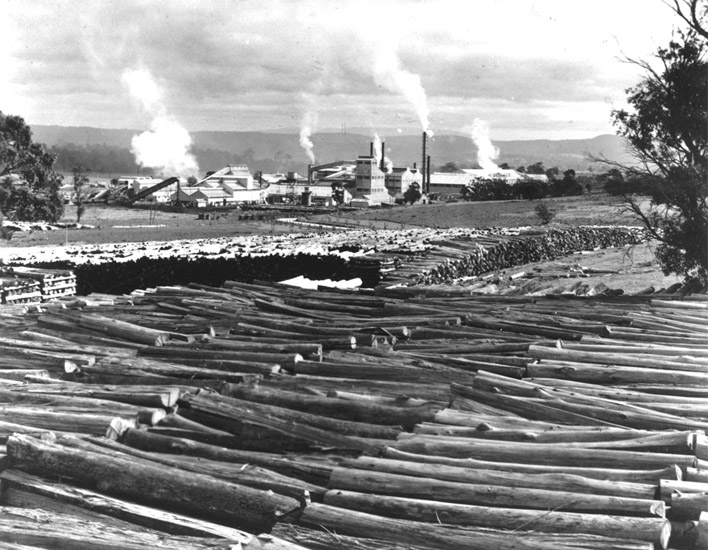

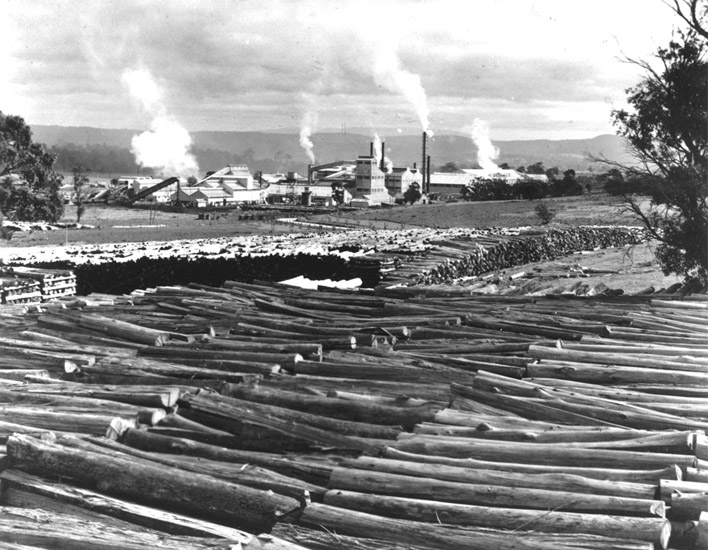

First developed by the ancient Chinese, paper became a key manufactured trading commodity in modern times, requiring vast supplies of wood pulp. Shown here are pulp logs awaiting shipment in Victoria, Australia, in the early 1940s. (Library of Congress)

From the early eighteenth century onward, pulp and paper production became increasingly industrialized. By 1700, the so-called Hollander beater was invented in the Netherlands: it used a wheel outfitted with metal blades that cut water-logged rags to produce pulp more efficiently than older stamping mechanisms, which crushed rags with wooden hammers. The first papermaking machine was invented in the late 1790s in France by Nicholas-Louis Robert; patented in England in 1801, Robert sold the patent in part to the London stationers Henry and Sealy Fourdrinier, who perfected his design. Capable of producing large continuous sheets in huge volumes, the paper-makers like it today are still called Fourdrinier machines.

But the European paper industry was plagued by shortages of raw materials for pulp that dated almost to the first introduction of paper to Europe. These shortages only became more intense in the nineteenth century, when expanded literacy increased print production. Experiments with materials more plentiful than rags began as early as the 1720s and included, over the next hundred years, books printed from pulped pinecones, grass, straw, corn husks, and thistles. Inexpensive ground-wood pulp came into broad use by the 1840s, although the resulting paper was brittle, off-white, and short lived. Subsequent advances in the chemical treatment of wood pulp in America and England improved the quality of paper while keeping costs low, but this treatment has often been blamed for environmental pollution. By the later nineteenth century, paper was used to make everything from boxes to shirts to tables.

Today, over 99 percent of all paper is made from wood pulp. Industrial pulp and paper production remains a multibillion-dollar, multibillionton industry. In 2000, the United States was the world leader in pulp production, at just over 30 percent of the market, although in world paper and paperboard production it (at 26.4 percent) was topped by Europe (30.9) and China (29.6). In 2001, paper manufacturing in the United States reached over $14 billion in exports and over $18 billion in imports.

J.E. Luebering

See also: Alphabet, Aramaic; Alphabet, Cyrillic; Alphabet, Greek; Alphabet, Latin; Alphabet, Phoenician.

Bibliography

Bloom, Jonathan M. Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

Hunter, Dard. Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft. New York: Dover, 1978.

Kouris, Michael, ed. Dictionary of Paper. Atlanta: TAPPI, 1996.