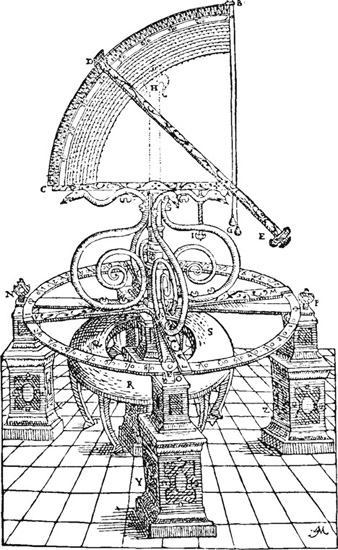

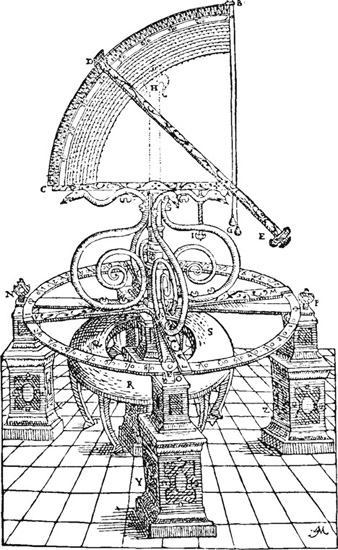

Before the development of the cross-staff, many mariners used a quadrant (pictured here) to determine when a ship was in the latitude of a desired harbor. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

Used by many mariners to determine latitude before they began to use the cross-staff.

Like the cross-staff, which measured the altitude of a celestial body, the quadrant incurred inaccuracies that allowed their users to know only their relative position and not their exact location. Still, such information told a ship’s crew when they were in the latitude of their desired harbor.

Used for centuries by astronomers and architects, the original quadrants were essentially a quarter-circle made of either wood or metal with two pinhole sights through which one delineated degree of latitude in relation to the Sun or another star. Some time before the mid-fifteenth century, the quadrant began to be used at sea by the Portuguese. The earliest sea quadrants often cut out the degree demarcations that coincided with the names of various ports, ensuring that the least-educated mariner could use the instrument. Of course, as sailors became acquainted with geometry, degree gradients soon returned to the quadrant and mathematics became an integral part of navigation. Christopher Columbus is known to have taken a gradient quadrant on his voyages as his 1493 journal reflects. However, with the introduction of the cross-staff, particularly the back staff, the quadrant was superseded.

By the mid-seventeenth century, the Davis Quadrant, a much-improved variant of the back staff, was widely used by mariners. The Davis Quadrant, or for Europeans the English Quadrant, was used like the cross-staff except that one’s back was to the object being observed.

Realizing that inaccuracies were prone to occur, especially in rough weather or in the tropics, mathematicians, navigators, and the Royal Society all became involved in developing a better instrument for finding a meridian altitude needed to determine latitude.

Various quadrants were developed and tested, but the Hadley Quadrant (1734), or more properly octant, revolutionized navigation and remains the basis for most marine instruments today. Like the magnetic compass and Harrison’s Chronometer, the Hadley Quadrant began a similar era in achieving accuracy. Several eminent scientists invented similar instruments, like Isaac Newton and Edmund Halley, but John Hadley gave the first account of it to the Royal Society in May 1731. The instrument was specifically designed to reduce any distracting motions when making an observation of latitude. This allowed mariners to determine their latitude with a precision heretofore unknown. An excellent contemporary description of how to use a Hadley Quadrant can be found in various editions of John Hamilton Moore’s The New Practical Navigator (1800).

The ultimate refinement of the quadrant was effectively completed in 1764 with the creation of the sextant. The sextant was the primary and most accurate marine instrument until the introduction of satellite navigation in the later twentieth century. Until the advent of the sextant, marine instruments were used to observe the meridian altitudes of the Sun or stars to help sailors ascertain their latitude. The sextant, however, was designed to measure lunar distances and, when used in conjunction with lunar tables, made it possible to observe longitude. Until the late nineteenth century, sailors kept both an octant and a sextant to make their separate observations. Gradually, however, it was soon realized that the sextant could perform both observations and the octant fell out of favor.

Before the development of the cross-staff, many mariners used a quadrant (pictured here) to determine when a ship was in the latitude of a desired harbor. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

Maritime instrumentation steadily evolved from the fifteenth century onward as European mariners, and their backers required the ability to more safely traverse the globe. Medieval quadrants soon became too unreliable to be used when the distances became more vast and the missions more vital. Yet the name remained for the instruments that refined the quadrants’ ability to affix the meridian altitude, most notably the Davis Quadrant and the Hadley Quadrant—neither a quarter-circle as their names imply. The development of these instruments was crucial to the age of discovery and empire.

Alistair Maeer

See also: Navigation.

Fisher, Dennis. Latitude Hooks and Asimuth Rings: How to Build and Use 18 Traditional Navigational Tools. Camden, ME: International Marine, 1995.