A personal or formal institutionalized system of beliefs that pertain to the existence of and obligations to a deity.

Religion, as a system of cross-cultural communication, has always been connected to commerce. The connections between the two realms have existed throughout history at changing levels of intensity and with varying dynamics. These links have intrigued both policy makers and those who are active in the realms of religious and academic research. The relationships challenge the scholar with theoretical and practical questions. Should economic activity be subject to religious ethics and morals? What is the attitude toward the accumulation of wealth? What is the role of tradesmen in the expansion of religion?

These problems also relate to the variance between religious and cultural traditions. Since Max Weber’s study on Protestantism appeared, and even before, the issue of the correlation between Protestantism and capitalism in content has been debated. This study sparked a series of inquiries on the economic and political differences between Catholic and Protestant countries and between Christian and non-Christian societies. According to this commentary, the “spirit” of Protestantism was conducive to capitalism. Other religious traditions and the historical activity of religious organizations have raised other questions about the relationship between economic institutions and religious ones.

Religion as a Construction of Social Reality

The influence of religion on economic and social life originates, in part, from the role religion plays as a means of cultural communication and as a construction mechanism of social reality. Religion constructs the consciousness and the worldview of the members of a society. In other words, it defines the worldview and the values, which affect social conduct. Therefore, religion is central to our understanding of the differences between societies in matters of trade and economic activity.

Another important role of religion, which derives from its role in constructing the individual and collective worldview, is as a unifying system of shared values and meaning. The religious institutions provide the framework for the socialization on the society based on these shared values, including with respect to economic activity.

This influence on adherents’ worldview and on the inherent societal paradigms also affects the attitude toward trade. Religious values favoring trade and accumulation of wealth are spread in society through the education system (formal and informal), the legal codes, and other direct and indirect ways.

The role of religion in society and in commerce could also be explained by its function as a mechanism for explaining the uncertain and unknown. Trade, by definition, is also concerned with the ambiguity of the future and with risk and uncertainty. In this respect, it might not be surprising that contacts between trade and religion existed throughout history and that the two promoted each other in cross-cultural encounters.

Religious Values, Business Values, and the Rise of Capitalism

Religion was affected and shaped by economic and political development, and trade (or economic development in general) was influenced by religion, both as an inherent part of collective behavior and as a set of norms. Adam Smith, Thomas Robert Malthus, and others have stressed the role of religious values in economic growth.

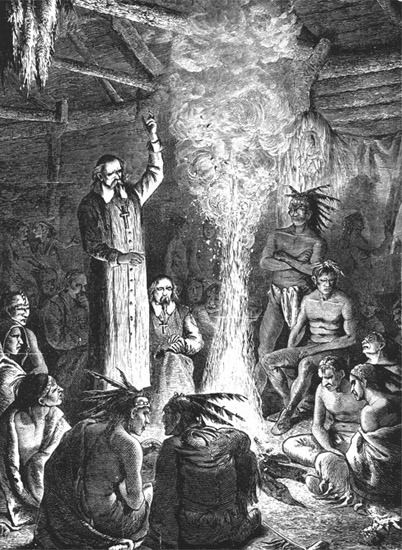

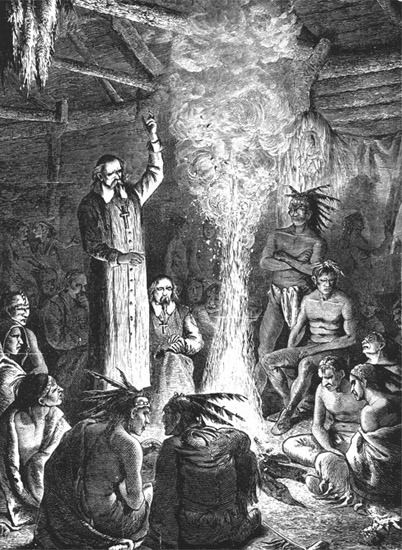

Many religious cultures could be interpreted as both advancing trade and discouraging it. In the case of the Jesuits—shown here preaching to Native Americans—they preached the idea of salvation through work. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

Religious indoctrination is specifically effective in making the work ethic a call and duty of believers. This is especially apparent in Protestantism. Values such as hard work, diligence, material ambition, thrift, and the place and importance of such things as property rights and commitment-to-honor contracts are hailed in their doctrine as contributing to economic development. Religion and religious authorities, therefore, play a vital role in shaping economic growth.

Max Weber’s prominent study The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism is perhaps the most significant contribution to the discussion on the impact of religion on economics. The study has stimulated much research and debate on its conclusions and explanations.

Weber intended to explain why some influential phenomena took place in the West (North America and western Europe) rather than in other places in the world. The economic conditions in South America and southern Europe, which were (and still are) predominantly Catholic, were contrasted with those of the Protestant countries of northern Europe and North America.

Weber explained the relative development of the West with reference to several unique features of Western civilization in the modern period, such as the specific forms of science, art, education, and organizational and political structures (bureaucracy). All these features share a common attribute: they are based on the concept of rationality. Capitalism, another important force that arises in Western civilization, is also based on rationalism, according to Weber. This does not imply that the human passion to accumulate and possess is a new or Western phenomenon. However, unlike other economic forms, capitalism is based on rational ideas of free work, the separation of enterprise from the household, and the establishment of accounting as the foundation of business.

Weber then sought the roots of rationality, which determined the course of economic development of Western civilization. He concluded that the rise of rationality depends not only on the usage of technique and law but also on the ability of people to think rationally and to base their way of life on rationality. Since religious forces define our worldview and ethics of living, they also determine the development of capitalist economic thought. Protestantism, Weber concluded, is the key to the development of Western societies.

Several core dogmas of Protestantism (especially Calvinism) contribute to the Weberian theory. At the center of Protestant theology is the doctrine of the “glory of God,” which means that every human action should somehow contribute to the glory of God. The way for one to glorify God is through one’s “calling,” which could be identified as the second pillar of the Protestant ethic. Weber viewed this as a foundation of the thesis that Protestant theology and ethics lead to capitalism. Martin Luther emphasized that each occupation—teacher, farmer, ruler, or soldier— should be used to glorify God. Thus, anyone who carries out his job faithfully and helps his neighbor is glorifying God. Carrying out the job faithfully means an ethical stress on the value of hard work. Work, along these lines, is not only the best prophylactic against a sensual, immoral life but also a “calling” to glorify God.

Another significant principle is that of predestination. Each person is predestined to become either a believer or a nonbeliever. While the believers and faithful to God are predestined to achieve heavenly salvation, the nonbelievers are not predestined to be doomed to hell; it is, rather, their choice not to become faithful that destines them to be condemned. Lutheran theology stresses this particular facet as a comforting, socializing, and conforming element in its doctrine. Calvinism is different in that it holds that people cannot evade their destiny.

The social consequences of the adoption of these two elements, combined, could be a strong sense of individualism inserted through religious values. Since an individual’s salvation is independent of his or her social connections, no one can change the destiny of another; only the individual can change his or her commitment to glorify God. Given that the way to glorify God is to be engaged in hard work, hard work is the only way to promote the possibility of salvation. Thus, a life of stern, hard work is the key to salvation. Spending time on nonessential activities, for example, on leisure activities and idle chatter, is to be avoided. Time should be devoted to work, which is glorifying God, and to necessary activities (eating and sleeping). Weber called this “ascetic Protestantism.”

Those who adhere to ascetic Protestantism perceive the consequences of hard work and thrift as economic success. Those who are economically successful are those who have worked harder and demonstrated thrift. They thus bring more glory to God, fulfill their calling, and consequently are guaranteed heavenly salvation. Those who accumulate wealth should not use it for leisure, individual pleasure, or early retirement from their work (their calling), because these actions show contempt for God, rather than deifying and venerating Him. Donating money to philanthropic causes is also disapproved of more often than not, since the poor, if they received charity, might be distracted from fulfilling their calling and working to glorify the name of God. Since profits cannot be used for personal pleasure or for giving up work, the only alternative is to invest the profits toward the growth of production. This creates an infinite cycle of investment and profit, which is consistent with the logic of capitalism. Hence, this is the link between capitalism and Protestantism. However, this does not imply that Calvinism was a vital element in the growth of capitalism or that the two are bonded in every aspect of Protestant attitude.

Similarly, one can point to other obstacles to economic development in other religious traditions. Hinduism, for instance, with antimaterialist values and a caste system, can be thought of as a central element in Indian culture that is opposed to economic growth, while Buddhism eulogizes the mendicant monk who travels light and remains free of economic concerns to engage in a life of contemplation. The New Testament of the Bible itself says, “Blessed are the poor, for they shall inherit the earth.” Many in the West perceive Islam as an obstacle to free-market economic forces. The fact that classical Islam sees no separation between religious and state policies adds to this perception. According to Weberian theory, Confucianism contributed to the low level of economic development in China. Since Weber wrote his book, however, some other cultural explanations have actually come to acknowledge Confucianism as a major contributing factor in the economic growth of Chinese communities outside China.

Weber’s cultural explanations raise several conceptual problems. First, it could be that other values, not religious ones, had the most impact on individual choices regarding business and consumption and, as a consequence, on the development of capitalism. Issues such as the need to sustain one’s immediate environment (family, kin, tribe, or country) might play a more vital role in the formation of capitalism. Religion, as also maintained by Weber, only reinforced the development of capitalism.

As with every religion, one could find elements in Calvinism that are unsympathetic toward the accumulation of wealth and toward a free-market economy and that could have been counterproductive to the development of capitalism. This distrust of wealth and discouragement of accumulating wealth could be demonstrated in several Calvinist teachings. Substantial differences between Calvin’s teachings and those of his followers were pointed out in several post-Weberian studies. Calvin himself was antagonistic toward the amassing of capital and was wary of economic success. A distinction between Calvin and some of his followers and interpreters, who linked prosperity and heavenly election, could therefore be drawn. According to these studies, only later Calvinism understood economic success as an emblem of righteousness and rationalized economic success.

As demonstrated earlier with the example of Confucianism, many religious cultures could be interpreted as both advancing trade and discouraging it. First, regarding Catholicism, it has been found that many Catholic organizations acted in the same manner as the Protestant ones and held the same values of salvation through work. An example might be the involvement of Franciscans and Jesuits in missionary work and the position of some of the missionary activities on the value of work as Christianizing the “savages” in the Americas and Africa and assisting in their salvation.

It could also be said that Islam, as a religion of merchants, is particularly attentive to their needs. Other religious traditions also have ambiguous, contradictory, and sometimes ambivalent positions toward trade and wealth. While parts of the doctrine stress communal and spiritual values (that might be thought of as contradictory to economic development), other elements in the same religion might stress the importance of commerce and of the merchant in the world and create favorable conditions for trade in the religious values settings. Moreover, the same religious dogma is interpreted differently in different periods or different regions.

In the medieval period, some Catholic ports in Italy were the most advanced centers of trade; some “Protestant” areas were highly influenced by Catholic “values.” In other words, Weber’s work also stimulated a lively debate on both the role of religion in economics and its impact on commerce and economic policies. For that reason, several alternative explanations to the links between religion and trade should also be considered.

Religions and Political-Economic Institutions

Links between religious institutions and political-economic institutions, and the impact religion has on individuals’ worldview, values, and actions, could be an alternative organizational explanation to the dynamics between religion and trade. Religious institutions sometimes endorse a certain economic policy, which they prefer to others for various reasons. The endorsement of a certain policy could mean, in practice, legitimacy for a certain regime (or regime type) and mobilization (through the religious institutions) of the believers to support or oppose a variety of policies.

The advent of Protestantism, referred to by the Weberian argument, reflects the diminishing of institutional control by the Catholic Church. The same loss of control, which brought about availability of opportunities in the religious realm, inspired experimentation in new philosophy (Enlightenment), new political ideas (political revolutions and civil wars), and new economic development (age of discovery and imperialist expansionism). Several variables affected the development of both capitalism and Protestantism. The organization of the Protestant churches is more compatible with decentralized economics and politics, with the expansion of trade, and with pluralist forms of organization. Moreover, as in the case of Islam, Protestantism might have attracted the merchants, who viewed the religion as promoting their interests and as providing them more opportunities than other denominations.

Some studies describe the “development” of religions as correlating with the economic development of societies. In other words, the explanation could be found not only in the specific religious tradition but also in its place on an imaginary “development” scale. Hunter-gatherer societies, which are usually not organized in permanent settlements, and nomadic societies tend to have different religious formations than those of agricultural and urban societies.

Islam and Christianity, for example, were founded and followed by people engaged in urban professions. Both of these religions have strong worldviews, firm religious ethics and desired conduct, and norms of institutional behavior in reference to political-economic issues.

Many animistic religions are less concerned with the complexities of urban and transcultural political economy, since they are connected with a localized culture, with its regional settings (i.e., prominent geographical features), and with less complex structures of government and trade. Judaism, which is a dynamic religion that has developed its social and ethic structure over time, evolved from a religion of nomadic shepherds, who traded mainly in livestock, to one of urban dwellers. During the same period, currency replaced barter exchange, trades became professionalized and specialized, and (almost) everything became a commodity.

As a side effect of this complexity, tradesmen are also favored members of religious organizations. Any religious group, principally as it begins to organize, institutionalize, and become more complex, needs resources in order to function. This is when the involvement of the group in economic affairs begins, whether or not that is its original motive. The need for funds might be satisfied when the church obtains a tithe from its devotees. The organization is then reliant on the more well-to-do members for the majority of the contributions. When a member becomes richer, he is not stigmatized, but praised for the product of his work. Those businessmen who donate money are essential for the support of the religion, as the Buddhist example demonstrates.

Most religions founded in the modern era, such as the Baha’i Faith, consider slave trade (and other sorts of trade, such as the trade in arms, prostitution, or drugs) illicit. Religions that devel oped in societies where slaves were part of the social structure regarded slave trade as legitimate until a change in norms occurred. Nowadays, slave trade is banned by most mass religious movements.

Different economic and political theories have had different ideas about the matter and about connections that should exist between religion and trade. Without the separation of church and state, interests of the religious institutions are usually united with those of the state, and these interests and ethics are incorporated in the business world. In classical Islam, for example, there was no distinction between religious and political authority. However, because the interests of Caesar, the secular regime, and God, the spiritual authority, were different, tensions between the two institutions on questions of desired economic policies, trade conduct, and financial institutions emerged.

These tensions intensify in regimes that are perceived by the religious authorities as hostile or anticlerical. The religious authorities might institute alternative organizations that challenge the political authority and aim to undermine its influence and legitimacy.

In communist countries, the church and the regimes are antagonistic and the economy is supposed to be controlled by the state. However, since the church provides an alternate source of authority in many communist countries, the authority of the regime, also over the economy, is undermined. The most significant example of the power of religious institutions is Poland, where the Catholic Church was the main alternative to the regime and played a central part in undermining the totalitarian regime and in supporting an independent trade union, Solidarnosc (Solidarity). In other communist countries, the church was less significant, but also played a part in democratization and transformation to a market economy.

Marxism, as a social and political interpretation of the world, rejects religion as a conceptual element, even in its post-Enlightenment, separated-from-the-state, form. Karl Marx said religion is the opiate of the masses. However, his analysis of the relationship between religion and political economy does not incorporate that famous metaphor. According to Marx, religion is a mechanism produced by society and the state to divert the attention of those oppressed by the system from their miseries, “Religious suffering is at one and the same time the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world and the soul of soulless conditions.”

Religion, in Marxist theory, provides logic about the world around us and makes sense of the injustice and domination. Indeed, many religious traditions attempt to explain societal systems, which are neither equal nor “just” in the Marxist view. Classical Hinduism, for example, explained the nonegalitarian caste system as part of a holistic worldview. Some Protestant groups explained poverty as a heavenly “punishment,” while during some periods Catholicism explained the same phenomenon as leading to divine grace.

Many religious systems provide justification, and encouragement, for the accumulation of wealth and for trade. Therefore, religion is a “false” system of meaning. It provides the believer with a false consciousness and with the false hope of salvation that turns the perception of oppression upside down. The believer, therefore, either has not “found himself” yet or has “already lost himself again.” The fight against religion is the struggle against the inversion of the consciousness to achieve “real” happiness, not one that is derived from the illusions of religion.

At the organizational level, religion and trade were also sometimes unified in their interests. Religion and trade were forces that brought about intercultural communication between Asian and Western (European) people. The mission of the imperialists, for example, bound religion (or the mission to convert the “savages”) with trade (or the need to exploit those same savages to yield profit).

Correspondingly, it has also been found that increased involvement of religious authorities in politics can hinder economic development. As mentioned before, several studies have been conducted on the way in which different religious traditions affect economic performance and attitude in a society.

For example, a negative correlation has been found between the level of church attendance and economic growth. Yet, it has been found in other cases that progress in trade and industry acts positively in response to some religious traditions. Specifically this could mean that the greater the power of the religious institutions (if attendance depends on this power), the lower the chance of a high rate of economic growth.

The link between religion and political economy is also significant in religion’s support for preserving the current social order. Religion serves as the basis of conservative politics, which represents a preference for the existing order of society and an opposition to all efforts to bring about essential or fundamental changes. According to some economic theories, the existing economy and its related inequalities are well justified. Religion and the religious leadership give legitimacy to the existing social order, in which some are more fortunate than others in the accumulation of wealth, some have higher status by merit of birth (aristocracy), and some inherit the fortunes of their parents.

This support for stability rather than change, for conservatism rather than reform, also affects religion’s attitude toward trade. Tradesmen fear that reform might label their commerce illicit and create political instabilities that would cause rapid change of trade partners. However, this support of the religious institutions for conservative economics, although usually favorable for the merchants, could also hinder tradesmen’s causes, for example, if state control over some potentially profitable market were removed or new markets opened up.

This attitude of religious institutions, in conjunction with the fact that most religious doctrines are ambivalent on the question of the accumulation of wealth, was a major contributing element to the creation of religious sects. Dissatisfaction with the “pragmatic” attitude of religious institutions encourages the creation of sects. Many studies find that most followers of sects and new religious groups were those who were not successful in accumulating wealth and who were looking for an alternate system, one that upheld “true riches,” which would be achieved at salvation and not prioritized according to the “corrupt” accumulation of wealth in this world. The followers who came from the underprivileged and alienated strata were likely to identify those things they were deprived of as evil or, at the very least, as insignificant and disagreeable. The rejection of those unfavorable earthly values and commodities would bring about “true” salvation, in the form of the second coming of a messiah and a better life in paradise (this is especially evident in some sects of Hinduism, which attracted the poor and underprivileged, promising them a better life in the hereafter). It should be mentioned, however, that recent studies find that many of those who join new religious groups belong to the middle classes, rather than the lower classes, and are not necessarily those who are economically or culturally marginalized.

Religion as a Regulator of Trade

The links between religious institutions and regimes have influenced the regulations regarding trade and the attitude of different polities toward trade and commerce. Religions reflect the political economy of their society also in relation to trade norms, which change over time. These interactions and dynamics between religion and trade also show that trade and religious policies influenced each other.

Each religion mentioned so far has established a set of norms regarding trade. These might represent societal attempts either to establish moral divisions between moneymaking and religious piousness or to reconcile them. In most religions, for example, there are some goods or trades that are banned. These might include trade in human beings (slavery), in prostitution, in drugs and alcohol, in types of food (such as nonkosher commodities in Orthodox Judaism), and in weapons. Some religions and traditions also limit trade at specific times (e.g., the Jewish prohibition on work and trade on Saturdays) or for specific individuals. The treatment of commodities, especially slaves and livestock, is also regulated by religious codes. The abuse, mistreatment, or over-employment of slaves (and livestock) is outlawed in the biblical codes.

Several trades or economic methods are also outlawed in religious codes. In medieval Christianity and Islam, for example, usury (the lending of money at inordinately high rates of interest) was forbidden. Thus, trades such as money-lending became identified with the religious minorities in Muslim and Christian countries, namely, the Jews. Modern Islam developed the concept of Islamic banks, whose arrangements do not contravene the ban on usury, yet allow modern banking to proceed. Similarly, Catholicism and Protestantism found ways to allow banking without usury.

The issue of usury could be essential to the encouragement of investments. The issue of investor protection is treated differently by various religious codes, and it influences the systems of protection and encouragement available to investors. In a Weberian attitude, it could be claimed that Catholic and Protestant countries have developed different mechanisms to deal with debt and lending. While the creditor is more protected in the Protestant system, the investor might find a better climate in the Catholic system.

Individual Religiosity and Trade in the Modern Period

The diminishing power of religious institutions in the modern period, as influenced by the Enlightenment and the separation of church and state in many Western countries, created the perception that with secularization the influence of religion over trade and its links with trade have also weakened. However, the impact of religion on the individual is less affected by the decreasing power of institutionalized religion. Trade, which is conducted by individuals but subjected to institutional regulations, continues to be affected by religion. First, at the normative level, religion still affects the worldview and values of the individuals who engage in commerce. Individual religiosity also affects a person’s position regarding current economic trends, such as liberalization and globalization, which are widely opposed by religious groups. Individual religiosity still expresses itself in the commercial activity of religious organizations. Some of these organizations have adopted modern marketing techniques such as using modern and global media and modern consumerist methods to attract new believers to their religions.

Another way in which religion and economics are tied are the linkages between religious activity and trade in religious objects, especially during pilgrimages and religious festivals. The trade in Christmas paraphernalia reaches to trillions of dollars each year. In the United States alone, each adult spends close to $1,200 each year (on average) on holiday-related shopping. Similarly, the number of sheep sold to Saudi Arabia in each hajj month constitutes an important portion of sheep consumption in the Muslim world.

Other profits include travel expenses for pilgrimages, specialized food (e.g., kosher food and especially wine and matzo for the Jewish holiday of Passover, when as much as 40 percent of annual kosher food sales take place), icons, amulets, sacrifices, books, and many other items of commerce that are linked to traditions and religions.

Individual religiosity and commerce are also connected in the regulations that many modern states impose on the relationship between the business world and religious activity. Most human rights and national revolutions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries advanced a prohibition on discrimination on the basis of individual religiosity. Religious organizations are also regulated by the state. In the United States, as well as many other countries, religious activities are not supposed to yield profits, and churches are considered nonprofit organizations.

Tamar Gablinger

See also: Buddhism; Christianity; Hinduism; Islam; Judaism.

Bibliography

Armstrong, Karen. A History of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. New York: Knopf, 1994.

Barro, Robert J., and Rachel M. McCleary. Religion and Political Economy in an International Panel. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, no. 8931, Cambridge, MA, May 2002.

Berger, Peter L., and Thomas Luckmann. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Garden City, NY: Anchor, 1966.

Bourdieu, Pierre, and James S. Coleman, eds. Social Theory for a Changing Society. Boulder: Westview, 1991.

Fieldhouse, D.K. The West and the Third World: Trade, Colonization, Dependence and Development. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

Fones-Wolf, Ken. “Religion and Trade Union Politics in the U.S., 1880–1920.” International Labor and Working Class History 34 (1988): 39–55.

Hamilton, Malcolm. Sociology of Religion. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Jeremy, David J. Religion, Wealth and Trade in Modern Britain. New York: Routledge, 1998.

Johnstone, R.L. Religion in Society: A Sociology of Religion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1998.

Raines, John, ed. Marx on Religion. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002.

Robertson, Roland. Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture. London: Sage, 1992.

———. Religion and Global Order. New York: Paragon House, 1991

Smith, Christian. Disruptive Religion: The Force of Faith in Social Movement Activism. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Tawney, R.H. Religion and the Rise of Capitalism. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1926.

Viner, Jacob. Religious Thought and Economic Society. Durham: Duke University Press, 1978.

Vries, Barend A. de. Champions of the Poor: The Economic Consequences of Judeo-Christian Values. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1998.

Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. New York: Scribner’s, 1958.