Use of the camel beginning around the first century C.E. helped promote Saharan and trans-Saharan trade. (Library of Congress)

The world’s largest desert, which today encompasses more than 3.5 million square miles, is bounded by the Atlas Mountains and the Mediterranean in the north and the Sahel steppe in the south, and stretches from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea.

Trade both within and across the Sahara has existed since prehistoric times, when the Sahara was considerably less dry, to the present. Pastoralism dates from at least 5000 B.C.E., with organized agricultural settlements beginning to emerge about 4000 B.C.E. By the second millennium B.C.E., long-distance trade had developed to such an extent that Mauritanian copper made its way to the Bronze Era civilizations on the Mediterranean coast. The still-ongoing tendency toward desiccation and the expansion of the desert may be dated from about 2500 B.C.E. In the time of Herodotus, it was still possible to traverse the desert by horse and chariot. Some of the most spectacular crossings include the famous pilgrimage in 1324 of the Mali emperor Mansa Musa to Mecca along with 15,000 followers and the invasion of Songhay by Ahmad al-Mansur ÷’s Moroccan army in 1590–1591, with 4,000 soldiers using over 9,000 pack animals and dragging along a number of cannons.

The gradual desiccation and growth of the Sahara between 5000 B.C.E. and 500 B.C.E. did not hinder further trade contacts either between Saharan settlements or between these settlements and the larger world. Part of the reason has to do with the introduction of camels by the Romans during the first centuries C.E., which remained vastly more efficient than horses for desert travel. The indigenous species long extinct, camels were reintroduced in the first century and were first mentioned in written records in 46 C.E. Because of camels’ efficiency in carrying weight, wheeled vehicles were abandoned in many places. The use of camels spread from southern Arabia both to the north and south of the desert from Somaliland. Their customary use extended as far south as the line running from the estuary of the Senegal to the confluence of the White and Blue Niles. On the camel journeys, nomadic Sanhaja groups traditionally provided guides and escorts for the caravans.

By the first millennium, the Phoenicians had established a string of city-states to mediate trade with desert peoples, which were in turn overtaken by the Carthaginians. In 450 B.C.E., the Greek historian Herodotus described the complex relationships among the Carthaginians, the nomadic pastoralists, and the sedentary farmers in the oasis settlements of Saharan North Africa—relationships that apparently stretched across the Fezzan of modern-day Libya and Tunisia. These ties connected into a much larger trading empire that included southern Spain, Sicily, Sardinia, Cornwall, Brittany, and the entire North African coast. Commodities that Carthaginian merchants carried from the desert trade included dye, leather hides, wool, ostrich feathers, ivory, wood, slaves, and gold.

The Romans probably used the fabled Garamantian Road, the most important overland caravan route at the time, to cross the Sahara into Aïr in the first century C.E. The reasons behind these forays remain a mystery, but they were probably a mixture of military opportunism and the need for slaves. Roman trade goods, including glass, jewelry, and Roman coins, found at a mountain oasis settlement in the southern Sahara dating from at least the fourth century C.E. suggest the extent of trans-Saharan trade.

Use of the camel beginning around the first century C.E. helped promote Saharan and trans-Saharan trade. (Library of Congress)

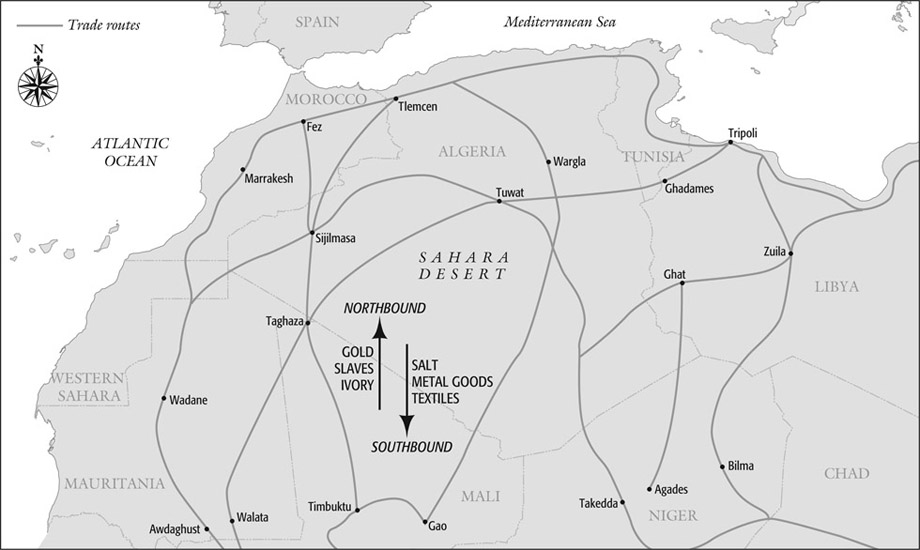

The main routes of the trans-Saharan commerce started from the southern Maghreb towns of Marrakesh, Sijilmasa, Tuwat, Wargla, and Ghadames, which were all linked to ports like Tunis or Tripoli, where swifter naval transport was available toward the East. Through the oases of Murzuk, Ghat, Bilma, and Taghaza, caravans reached their Sudan destinations at Tadmekka, Timbuktu, Awdaghust, Kumbi Sale, Kano, or Kukawa. Trade, however, flowed not just along the shortest North-South axes, but the East-West links toward Egypt and Asia also played an important role. In fact, a continuous eastward shift of the Sudanic centers is discernible. Central Sudanic states, like Wadai, Dar Fur, and Borno, partly owed their growing importance to the lively traffic of pilgrims.

The most important development in Saharan trade aside from use of the camel was the gradual introduction of Islam, first to North Africa and then across the Sahara, between the seventh and eleventh centuries. Early Muslim traders established far-flung networks of fellow Muslim agents across the desert and in sub-Saharan Africa in the centuries before larger-scale conversions to Islam. Islam provided a basic shared cultural framework that governed everything from personal behavior to contractual agreements and taxes. This common reference point made trade easier and made Islam attractive to African rulers and other elites. Conversion to Islam provided not only social differentiation but also access to education, favorable trade terms, and access to credit.

By circa 900 C.E., the North African city of Sijilmasa imported significant amounts of gold directly from the kingdoms of Ghana and Wangara. The trade route along the way to Ghana passed through regions where salt was plentiful. While Ghana was rich in gold, it lacked salt. As salt was brought to Ghana in exchange for gold, a gold-salt trade was established. This lucrative trade was controlled by the Almoravids in the north and Ghana in the south.

Saharan Trade, 1000 C.E. With the introduction of camels in the early centuries of the common era, it became possible for large trading caravans to cross the inhospitable wasteland of the Sahara between population centers in West and North Africa. Traders heading north carried gold, ivory, and slaves; commodities moving southward included textiles and metalware. Salt was frequently traded and used as a form of exchange. (Mark Stein Studios)

Most of the Muslim world remained relatively unaware of the gold wealth of sub-Saharan Africa, however, until the Mali emperor Mansa Musa spent so much gold on his pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 that worldwide gold prices remained depressed for years after his trip to the Holy Cities (Jerusalem and Medina). The Songhay empire that succeeded the Mali empire drew much of its ultimate power from controlling the sale of gold and slaves across the desert through the major entrepôts of Djenne, Gao, and Timbuktu. Evidence from travelers and commercial records suggests that the trade between Europe, the Maghreb, and sub-Saharan Africa became both large in volume and complex in the sixteenth century. This trade grew to such importance that in 1592 the Sa’adian sultan sent an expeditionary army across the Sa hara to take Timbuktu from the waning Songhay state, securing the increasingly important supplies of gold and slaves. The volume of exported gold has been estimated at one ton of gold per year during the Middle Ages. The inflow of precious metal greatly bolstered the political positions of the Maghreb states, on the one hand, and was crucial for European economies, on the other. Until the modern era, Europe remained on the periphery of the world economic system. A trade imbalance with Asia drained gold resources, which were in permanent shortage until the opening up of American supplies and Russia’s eastern expansion. The guinea coins of Britain indicate the origin of gold commonly used.

Consolidation of the long-distance trade system and regular communications are connected to the rise of medieval empires on both ends. The Almoravid empire even managed to take control of the entire area between Morocco and Ghana by 1055, including the major desert-edge nodes of trade. While economic dominance was clearly an important motivation, the fundamentalist Islamic regime also had an influence on commerce by abolishing all but the Koranic forms of taxation. Another more lasting legacy of the polity was the large quantity of gold dinars minted in Andalusia, unparalleled since Roman times. The necessary gold originated from the mines of Bambuk, the even larger goldfields of Bure, and Upper Volta, while the Akan forests were exploited at a later date. In the upper Niger region, Awdaghust and Kumbi Saleh were prosperous urban centers in the Ghana kingdom during the tenth and eleventh centuries, while Djenne, Timbuktu, and Gao emerged as important centers of commerce and culture in the Mali empire during the fourteenth century. Timbuktu was the most important distribution center of Saharan salt from a chain of slave-worked mines in Awlil, Taghaza, Taodeni, Bilma, as well as of Akan gold and kola nuts. While more obscure, the gold of the Kaduna valley and the town of Zaria also attracted the attention of the south’s specialized merchants, who were associated mostly with networks of trade diasporas, such as the Dyula, Djahanke, or the Hausa. Central Sudan has also seen periodic interference from Egypt. During the nineteenth century, nonindigenous so-called Khartoumers established a network of fortified trading depots in the region and invited massive mercenary armies that eventually overran, first, Darfur and, then, Borno. Their brief, but influential, presence came to an end with the establishment of the Mahdist theocracy.

Widespread desiccation along the most important trans-Saharan routes between 1600 and 1850 worked to shift production and distribution networks and rearrange social order, identity, and political alliances. After an initial period of crisis, both local and long-distance trade recovered and perhaps even exceeded their previous levels in some areas of the Sahara. One important factor in the recovery was the emergence of Sufi orders that took a strong interest in economic activities in addition to their more traditional concern for Islam and mysticism. These new Sufi orders provided access to important social networks, mediation, credit, and law enforcement that the social and environmental crises of the 1600s had largely eroded and helped stimulate economic activity.

Although nineteenth- and early twentieth-century colonial adventures did not directly interrupt either trans-Saharan or local trade, colonialism did manage to shift consumption patterns and indirectly changed which goods people produced as well as the trade networks that carried these goods between markets. Less gold went north, but the demand for slaves actually increased during the first decades of the twentieth century. The increasing ease of obtaining European firearms not only facilitated slave raids, but also caused increasing political instability and gradually raised transaction costs—particularly in terms of protection and mediation.

Life for most desert dwellers has changed little since the decline of colonialism in the 1950s and 1960s. Whereas multinational companies have discovered rich deposits of oil, natural gas, and other minerals in Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria, locals have generally not benefited from the growing international trade. Trans-Saharan caravans no longer ply the desert. But regional caravans are still crucial parts of local economies, carrying products between Saharan villages and especially between oases and desert-edge towns.

By the twentieth century, approximately 10 million slaves had crossed the Sahara, a number comparable to the Atlantic transports’ moderate estimate of 12 million. In the Mediterranean as in the New World, African slaves played an important role in the shaping of economies and societies. It appears that the Saharan trade involved a higher number of women and children, so the demographic impact of the two diasporas was different. The slave trade contributed to the prosperity of the Sudanic centers, although it is no longer seems tenable that slave raiding was the most important economic factor or social organizing principle in the rise of these powerful kingdoms.

The ancient trade across the Sahara remained important until the early twentieth century. The historical evidence does not support saying that the ocean ports conducted the bulk of Africa’s trade. In fact, the nineteenth century saw some of the most dynamic periods of growth in overland long-distance commerce, including that in the Sahara. Many projects for the construction of railways and hardtop roads crossing the desert from the colonial period were abandoned, and the only tangible results of the ambitious development plans seem to be the small airports of the oases still used by pilgrims on the hajj. The present-day overland routes between North and West Africa also still largely follow the traditional patterns.

Gábor Berczeli and David Gutelius

See also: Arabs; Berbers; Caravans; Dyula; European-African Trade; Gold; Mediterranean Sea; Oases; Salt; Slavery; Songhay Empire.

Allen, J.A., ed. The Sahara: Ecological Change and Early Economic History. Boulder: Westview, 1983.

Baier, Stephen. An Economic History of Central Niger. Oxford: Clarendon, 1980.

Boahen, Adu. Britain, the Sahara, and the Western Sudan, 1788– 1861. Oxford: Clarendon, 1961.

Cordell, Dennis. Dar al-Kuti and the Last Years of the Trans-Saharan Slave Trade. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Curtin, Philip D. Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Isichei, Elizabeth. A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Webb, James L.A. Desert Frontier: Ecological and Economic Change along the Western Sahel, 1600–1850. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995.