A popular trade item through the centuries, salt comes in various forms that together have over 14,000 current uses.

Sodium chloride, one member of this class of chemical compounds of which sodium is the base, has historically been used to preserve fish and meat, prepare cheese, and make butter, as well as maintain the health of humans, horses, and livestock. Others, including natron and saltpeter, have been used for mummification, manufacture of gunpowder, disinfectant, dyeing textiles, tanning leather, fertilizing agricultural fields, and making soap.

Demand for salt established the earliest trade routes on almost every continent: the cities of Jeri cho and Timbuktu were founded as salt trading centers hundreds of years ago. Credited with discovering natron, the Egyptians never became great exporters of salt, but they did develop a substantial trade in salted products. In around 2800 B.C.E., they began trading salt fish to the Phoenicians for cedar, glass, and purple dye. The Phoenicians in turn traded the Egyptian fish as well as North African salt and became one of the great economic powers of their day.

The Romans, who used great amounts of salt as a preservative, obtained most of it through conquest instead of trade. When Christianity took hold, its Lenten diet banned the consumption of meat during certain periods and created economic booms for those cities that could supply salt to preserve fish. In 1281, realizing that trading salt earned more money than making it, the Venetian government aimed to become the dominant commercial force in the Mediterranean by paying merchants a subsidy on salt. Venetian merchants then typically used these salt profits to send ships to India to purchase spices for sale in western Europe at low prices that undercut the competition. This salt-based trade led to the War of Chioggia (1378–1380) with Genoa, Venice’s chief competitor. The Genoese lost the conflict, and Venice remained the dominant Mediterranean trading center.

Northern states had an abundance of fish but lacked the salt needed to preserve their catches. They had to trade to sustain their economies, but salt was often laced with ashes, thus making the tricky process of correctly salting fish even more of a challenge. To ensure the quality of goods, the Hanseatic League was organized in Germany. The Hanseatics bought salt from many sources to supply the north and, since they supplied an essential ingredient, soon came to control the northern economies. The Danes fought a brief war with the Hanseatics in 1360 to regain economic power, but were defeated. The British and Dutch eventually developed enough clout to overwhelm the cartel.

For centuries, the British obtained most of their salt from their principal enemy, France. Concerned about this dependence, Elizabeth I guaranteed state-controlled markets to develop a salt industry in Northumberland, a region with significant amounts of coal to fuel the fires that would evaporate brine to produce salt. Unfortunately, British saltworks could not provide the sea salt needed for British fisheries, and no other type of salt was believed suitable to preserve cod. For the British, the solution to a lack of salt was to acquire the commodity through war or diplomacy from places that produced it. In the sixteenth century, Portugal had some of the best salt in Europe but needed protection from frequent attacks on its fishing fleet. Agreeing to trade salt for naval protection, Portugal permitted English ships to fill their holds with sea salt at the Cape Verde Islands. Salt became valuable enough to generate the profits necessary to justify paying an entire ship’s crew for several months labor. Salt was heavy, and the cost of transporting it always represented a substantial portion of the selling price.

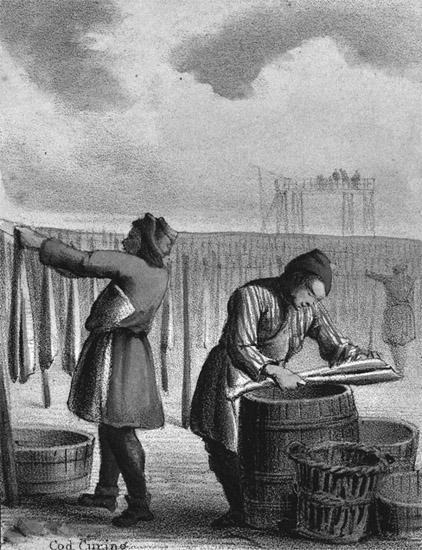

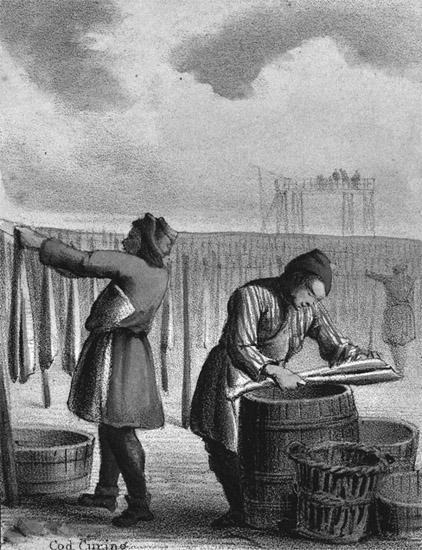

Because of its importance to the human diet and its use as a food preservative, salt has been one of the most universally traded commodities in human history. Shown here are men curing cod with salt in the mid-nineteenth century. (© Science Museum, London/Topham-HIP/The Image Works)

Through their salt trade, the British also came to play a supporting role in the slave trade. Most British rock salt came from Cheshire, which gained access to markets through canals that led to the port of Liverpool. Ships leaving Liverpool for America employed salt as ballast, then picked up cotton and other imports for use in British industry. Ships heading to Africa to collect slaves also used Cheshire salt as outbound cargo. Much British salt went to Ireland to preserve salmon, herring, pork, and beef. Then the Irish shipped their beef to slave colonies in the Caribbean as a cheap and durable source of protein.

America and the Salt Trade

In America, salt was needed for fish exports and furs. As a strong believer in mercantilism, Britain did not permit its American colonies to trade with other nations, but the rich American waters produced more salt cod than the British could sell. Rather than suffer financially to benefit mother England, Americans smuggled salt cod around the Atlantic. Settlers found additional profits by trading with Native Americans for pelts that would be salted for preservation and then sold on the lucrative European market. After achieving independence, the United States remained limited in the salt trade by its poor transportation network. To solve the shipping problem and expand the salt industry, legislators from Syracuse, a salt-producing town in New York, proposed the Erie Canal as an inexpensive route for bulk shipment of salt to New York City. As Americans moved farther from the coasts, they still preferred to trade for salt, rather than develop saltworks. Until the twentieth century, salt remained the leading cargo carried to North America from the Caribbean, mostly from the southern Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos.

The British also forced Indians to become dependent on salt imports, and this heavy-handed action ultimately prompted Mohandas Gandhi to start an independence movement. Since ancient times, India had a thriving salt industry, but the British decided to benefit the Cheshire salt makers by allowing them to take over the Indian market. As a result, the smuggling of illegally produced Indian salt became widespread. To stop this illicit trade, the British government imposed harsh penalties, including jail sentences, on smugglers and anyone who indirectly aided them. In 1930, Gandhi walked to the sea and broke the law by collecting handfuls of salt. Arrested for salt making, he ultimately forced the British to change their trade policy to allow individuals to produce salt for home use.

In the twentieth century, modern geology revealed that salt deposits exist in most places on the earth. No longer a rare item, salt lost its trade allure.

Caryn E. Neumann

See also: Cities; Food and Diet; Gandhi, Mohandas; Genoa; Hanseatic League; Mercantilism; Phoenicia; Slavery; Transportation and Trade; Venice.

Bibliography

Adshead, S.A.M. Salt and Civilization. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

Eskew, Garnett Laidlaw. Salt: The Fifth Element. Chicago: Ferguson, 1948.

Kurlansky, Mark. Salt: A World History. New York: Walker, 2002.

Nenquin, Jacques. Salt: A Study in Economic Prehistory. Bruges: De Temple, 1961.