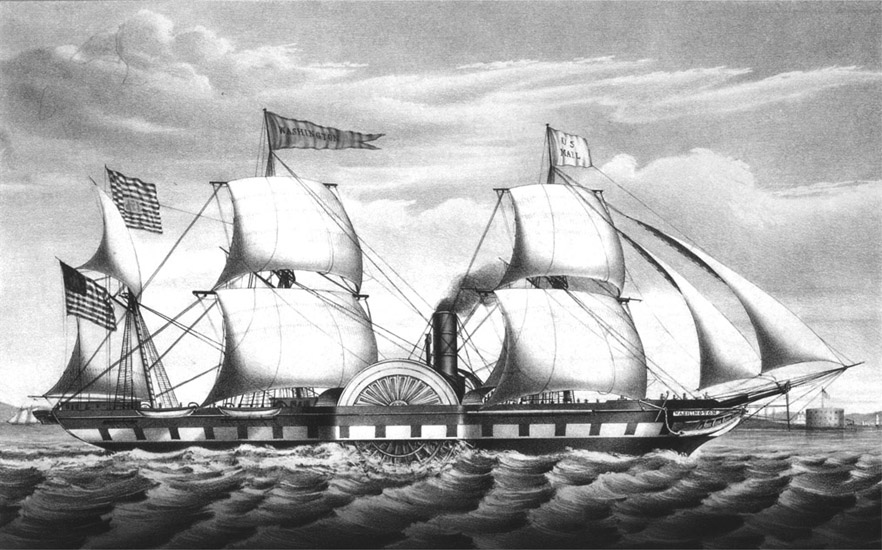

The steamship transformed international trade by allowing for faster and more predictable river and ocean transport. Shown here is the U.S. steamship Washington. (Library of Congress)

A new form of ship, which, after it came into wide use by the mid-1800s, revolutionized much of the transportation on which world trade was based.

The application of steam power to water transportation greatly improved long-distance transportation around the globe. Although steamships were eventually eclipsed as the primary vessels for oceanic and long river transport, they were a critical factor in beginning the creation of a global economy in the mid-nineteenth century.

The steamship transformed international trade by allowing for faster and more predictable river and ocean transport. Shown here is the U.S. steamship Washington. (Library of Congress)

Steamships saw their first commercial use in short-distance river trade within countries in the early 1800s. The high seas and lack of fuel en route precluded their use for transoceanic voyages until the late 1830s. By 1840, as these and other technical problems were overcome, regular steamship service was established between the United States

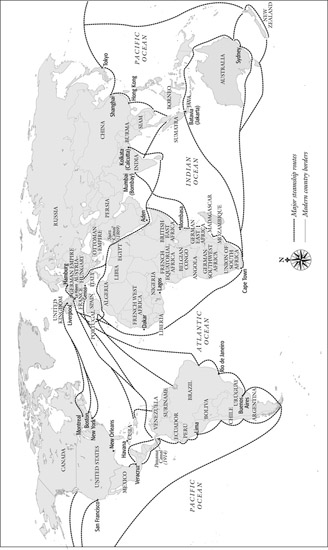

Steamship Routes, 1900 While the invention of the ocean-going steamship in the nineteenth century did not change trade routes significantly, it vastly expanded the volume of commodities traded. From the end of the American Civil War to the beginning of World War I, world trade grew from an estimated $8 to $39 billion. (Mark Stein Studios)

and Britain and the groundwork was being laid for such service between Britain and India.

Regular oceanic steamship service drastically changed world trade. Steamships, not dependent on fickle winds, could be faster and more reliable than sailing ships. This allowed much more predictable schedules for passenger, cargo, and mail transportation. There was a limit to the size and speed of sailing ships. Theoretically, steamships had no such limits. The freeing of long-distance water transportation from the limitations of sailing vessels made it much easier to increase the volume of world trade and give it the same level of reliability and punctuality that land trade within individual countries had.

Not surprisingly, steam engines began to power military vessels at about the same time they did commercial ones. Steam-powered gunboats were instrumental in Western imperialism in the nineteenth century. They gave Western warships a decisive advantage in speed, maneuverability, size, and firepower against non-Western wind- and manpowered navies, as Britain demonstrated with devastating effect in the Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1858) against China. The need for coaling stations influenced the geography of nineteenth-century Western expansion. Coastal areas and coal-rich regions were of utmost importance, so much so that Western powers often sought control over them early and directly when expanding their overseas empires. One of the most famous examples of this was the attempt by the American navy to force Japan to end its opposition to involvement in the world economy during the 1850s, a time when new American steamships were looking for fueling sources in the North Pacific.

In the early twentieth century, steamships were starting to be seen as antiquated. Although they were reliable in terms of speed and travel time, steamships were still unreliable in terms of safety. There were horrific and catastrophic mechanical accidents, like the boiler explosion that destroyed the USS Maine in 1898. By the 1920s, a new, more stable type of engine, the diesel-powered internal combustion engine, was replacing the steam engine as the favored motor for ocean transport. The new diesel ships carried cargo on the same routes pioneered by their steam-powered predecessors. However, petroleum, their base fuel source, would steer world trade and international conflict to regions often little touched in the age of steam.

David Price

See also: British Empire.

Headrick, Daniel. Tentacles of Progress. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

———. Tools of Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981.

Singer, Charles, et al., eds. A History of Technology. Oxford: Clarendon, 1978.