Scandinavian raiders, traders, mercenaries, and colonists renowned for their clinker-built, sail-powered ships.

The Vikings were instrumental in unifying several long-existing regional trading zones in western Eurasia by connecting northern Europe with Byzantium, the Islamic caliphate, and Central Asia by way of European Russia, thereby creating a cross-continental system that moved northern goods in exchange for silver.

Viking expansion was largely due to their ships, which performed equally well on seas and rivers, a European-wide climactic optimum, population growth in Scandinavia and the resulting demand for arable land, as well as the consolidation of petty chiefdoms within Scandinavia that helped to concentrate groups of warriors and traders eager for adventure and profit. But two coinciding phenomena catalyzed Viking expansion. In the Anglo-Saxon and Carolingian kingdoms of northwest Europe, Vikings found burgeoning commerce as well as rich monasteries to raid and ransoms to extract. In the East, the Vikings found recently pacified routes by way of Khazaria to the Muslim caliphate, which in the second half of the late eighth century minted unprecedented quantities of silver coins, or dirhams.

In the seventh and eighth centuries, the Frisians dominated the steadily expanding trade in the North Sea. Viking encroachment on this trade is clearly shown by new developments within Scandinavia, such as the growth of market/production centers (Ribe and Hedeby in Denmark, Kaupang in Norway, and Birka in Sweden), merchants’ graves containing imported goods, and fortifications. By the eleventh century, these commercial connections helped introduce local coinage, centralized kingship, and Christianity into Scandinavia. The Vikings also placed a Dane on the throne of England, colonized Iceland and Greenland, and helped found what would become a 700-year dynasty, the house of Riurik, in Russia.

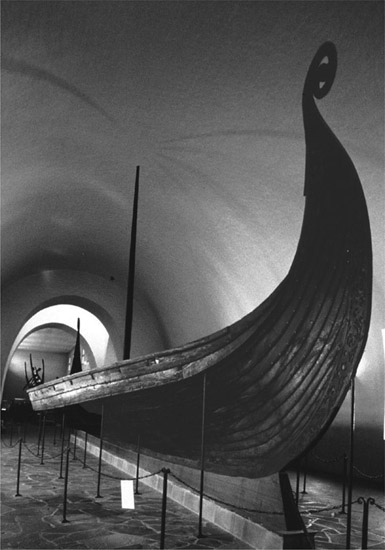

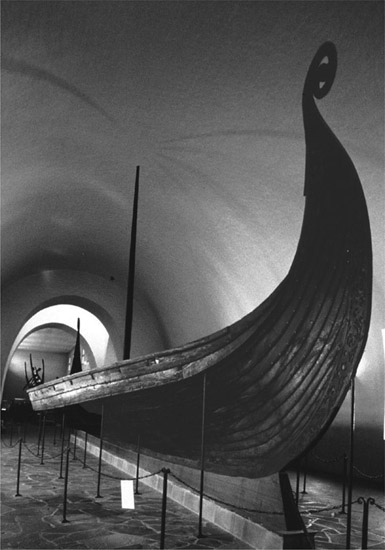

The Vikings were instrumental in unifying several long-existing regional trading zones. Viking expansion was largely supported by their ships, which performed equally well on seas and rivers. Pictured here is a sixteen-seater, an early ninth-century C.E. Oseberg Viking ship. (The Art Archive/Viking Ship Museum Oslo/Dagli Orti [A])

At the height of the Viking age, the commercial network extended as far west as Greenland, as far north as the White Sea, and as far east as Byzantium and the middle Volga River, where goods were exchanged using intermediaries with Central Asia. The Vikings’ primary motivation was to obtain silver, which was the standard medium of exchange. Using portable bronze folding scales, merchants assessed the price of goods and then cut the silver to desired amounts. In the early Viking age, vast quantities of silver flowed from the Muslim caliphate across European Russia to the Baltic. In exchange, merchants brought amber from the southern Baltic, swords from the Rheinland, furs, honey, and wax from the northern forests, ivory from the Arctic, and slaves from the Slavic regions. Along with silver, traders brought from the East glass beads and raw glass, silks, spices, and semiprecious stones. All these items were lightweight and easily transportable. Luxury items were traded further throughout northern Europe for soapstone (Norway), wine and swords (Carolingian empire), and lead (British Isles).

By the early eleventh century, the flow of silver changed directions, ceasing altogether from the East, which was replaced by west European sources. Scandinavian trade reoriented itself toward western Europe. But contact with the East continued in the following centuries. Luxury goods from the East, by way of European Russia, continued to flow into northern Europe.

Heidi Sherman

See also: Amber; Dirhams; Khazar Empire; Wine.

Bibliography

Clarke, Helen, and Björn Ambrosiani. Towns in the Viking Age. London: Leicester University Press, 1991.

Sawyer, Peter, ed. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.