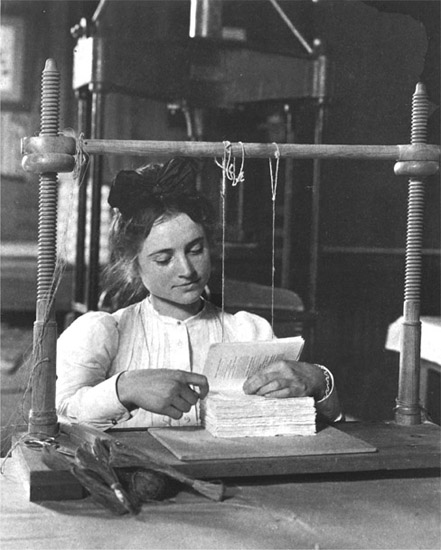

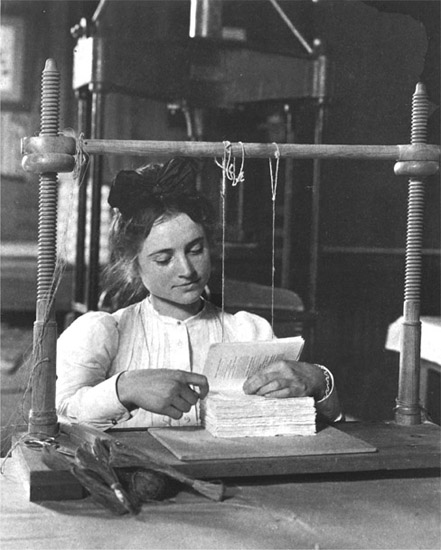

Women have been a major part of the workforce throughout human history. Shown here is a woman engaged in bookbinding in New York State around the turn of the twentieth century. (Library of Congress)

The role of women as active participants in trade and business has a rich and complex history from ancient times to the present day.

From the earliest times, women have endured in trade and in business even as the law envisioned men as primary breadwinners supporting families with their right to work central to maintaining their masculine sense of independence and autonomy. Women were viewed as wives and mothers, whose economic rights were mainly to be supported by a male breadwinner and protected by the state from any harm to or interference in that role by employment.

During ancient and medieval times, women remained in the background but still worked and produced items for trade. In drawings of cave dwellers, there are illustrations of woman making stone utensils, fishing, scraping with antler tools, cleaning animal hides, and foraging for food. In early Greek civilization, citizen-women who worked in trades such as wool and vase painting were respected as entrepreneurs. Female slaves worked in mines, food processing, and textiles. In later centuries, the wives of craftsmen and merchants often sent their babies to wet-nurses soon after giving birth so they could return to work alongside their husbands in the family business. In ancient Gaul, women were allowed to work with men as military combatants, construction workers, judges on tribal councils, and in cattle raising; roles open only to women included goldsmiths, prospecters, and priestesses or forecasters.

An ironic feature of early modern times was that a craftsman could not open a workshop if he was unmarried, but his widow was able to preserve her role as head of the whole workshop. Some women managed to keep their positions in the crafts and guilds, but this professional freedom in the Middle Ages was increasingly reduced as the guild laws began to exclude women from learning their crafts, except in lace making, where women in the sixteenth century retained a dominant position. Barbara Uttmann, the wife of a wealthy Annaberg patrician in Erzgebirge, Germany, introduced lace making in her region around 1560 and established an expanding and profitable industry that employed mostly women. Women were also active in the money trade and in other forms of trading, such as the cloth trade, where Dutch women, especially, appeared in the forefront of these types of businesses.

Women have been a major part of the workforce throughout human history. Shown here is a woman engaged in bookbinding in New York State around the turn of the twentieth century. (Library of Congress)

The Industrial Revolution led to the emergence of the factory system in which workers were brought together in one plant and supplied with tools, machines, and materials with which they worked in return for wages. There were rapid changes in the manufacture of textiles, particularly in England from about 1770 to 1830; this soon shifted to the United States, where the textile trade depended heavily on women and children in the factories. In the 1860s, entire families worked fourteen-hour days in the giant textile mills that lined the New England waterfronts, especially the coast that extended from Rhode Island through Massachusetts and New Hampshire to Maine. Today, the Industrial Revolution National Park in Lowell, Massachusetts, honors the women and children who toiled in these mills, under dangerous conditions, as the finished product of their labor made the New England textile industry a major part of international trade.

Another trade in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that depended on women for its success was bookbinding. Even though machines were invented for sewing books, women were still employed in many companies to sew them by hand, securing the forms to the cords at the back of the book. Women also edited newspapers and served as printers, working mostly as compositors, but they were barred from joining the unions, a situation that finally changed in 1869, when the Typographical Union became the first national union to change its constitution to admit women.

In the nineteenth century, among the few venues that allowed women to display their ingenuity and business skills on more than a local scale were the international expositions, popularly called world’s fairs, which grew out of the medieval trade fairs. At the Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876, there was a Women’s Building that displayed items of art, crafts, and inventions by women; this represented an early achievement in the feminist struggle for suffrage and equal rights. At the Glasgow International Exhibition (1888), there was a Women’s Industries Section that highlighted accomplishments, but it was at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago that women first played a prominent role at a world’s fair with a building that displayed female accomplishments in education, science, and the arts and industry and a World’s Congress of Representative Women that had a total attendance that exceeded 150,000. These culminated in the more condescending name of the Palace of Women’s Work at the Franco-British Exhibition, London (1908); the Women’s World Fair held in Chicago, April 18– 25, 1925, to demonstrate women’s progress in seventy industries and sponsored by Grace Coolidge, the U.S. first lady; and the rather striking historical display in the Women’s Section at the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition, Wellington (1939– 1940), one of the last fairs before World War II.

To make up for manpower lost to the war effort, large numbers of U.S. women, like this riveter, worked in defense factories during World War II. (Library of Congress)

One of the lingering images of World War II is Rosie the Riveter, the propaganda symbol of American women defense workers who put aside family responsibilities to take on the traditionally male stronghold of heavy industrial work, especially in aircraft production, munitions, and shipbuilding, as the range of jobs open to women expanded dramatically. This situation actually existed in other countries as well; early in the war, the British government recognized the need for child-care facilities if married women were to be brought into the workplace. However, segregation by sex was still maintained as women’s jobs were denoted as “assistant” or “helper.” When the war ended, discrimination against women by employers, unions, and the government returned “Rosie” to the domestic spheres of household maintenance and child rearing as male workers returned to these jobs. Many women saw no reason why they should keep a job in peacetime, but others did not wish to relinquish jobs to returning male veterans. By the 1960s, women began to enter skilled trades and professions that had previously been closed to them, such as carpentry and electricity.

On March 29, 1957, the Treaty of Rome, the founding document of the European Economic Community, was signed; women remain primarily affected by Article 119 of the treaty, which establishes “the principle that men and women should receive equal pay for equal work.” The article was not adopted in the interests of fair treatment of women but to prevent unfair competition through the use of cheap female labor. When social concerns became an issue in the 1970s, this article was used as the basis for directives aimed at improving working conditions for women.

One of the first images of women and trade in the New World is from an undated illustration in the collections of the New-York Historical Society that shows Iroquois women at work in a sugar camp; these same women taught the art of making maple sugar to subsequent English, Dutch, and French settlers of the seventeenth century.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, several generations lived under the same roof and everyone worked. Women often served as teachers in early “dame schools” in the mid-seventeenth century that involved more than hearing the lessons of neighborhood children. Many women supervised female jobs, such as teaching a girl apprentice how to spin, and kept busy with household chores, such as plucking a goose and carefully saving the down feathers for a quilt.

During the American Revolution, farm wives, who were helped by other family members, often took their husbands’ place on the farm, while their husbands served in the Continental army and navy. This pattern was repeated during the Civil War, as we learn from the diaries of Mary Boykin Chestnut and other women, from both the North and the South, whose diaries document their activities in taking over traditional male duties while their men were off fighting the war. At the same time, slave women toiled in cotton and woolen mills under white supervisors; turpentine camps and sugar refineries; food- and tobacco-processing plants; rice mills; hemp-manufacturing plants; foundries, where they put ores into crushers and furnaces; salt works; and mines, where they pulled trams. Many also were lumberjacks and ditch diggers. As early as 1800, slave women made up half the diggers on South Carolina’s Santee Canal, helped build the Louisiana levees, and worked on the slave crews that laid track for the southern railroads.

In 1881, the Knights of Labor extended membership to women over the age of sixteen; once this happened, women joined in great numbers. By 1886, there were 192 women’s assemblies, and an additional number of women joined formerly all-male assemblies. Some 50,000 women were members of the knights at its 1886 membership peak, approximately 10 percent of all the organization’s members but barely 2 percent of the more than 2.5 million women aged ten years and up listed in the 1880 census as gainfully employed.

Laws and programs were established by which the state provided entitlements and opportunities to men and women citizens over the course of the twentieth century. This started as early as 1908 when Muller v. Oregon upheld laws limiting women’s hours on the job.

Other high points include the establishment of the Fair Labor Standards Act (1938), social security legislation of the New Deal, the creation and modification of income tax laws regarding marriage, the passage of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the creation of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in the late 1960s.

The Women’s Bureau, part of the U.S. Department of Labor, was established by Congress in 1920 and is the only federal agency mandated to represent the needs of wage-earning women in the public policy process. Since 1920, it has been meeting this mandate by identifying the issues working women care about most and vigorously pioneering research and remedies to address them. For example, the Women’s Bureau investigated and reported on scores of women’s work issues, such as the conditions facing “Negro women in industry” in 1922, “older women as office workers” in the 1950s, contingent workers in the 1980s, and nonstandard-hour child care options in the 1990s (also known as flextime), to name just a few. It regularly publishes fact sheets on the status of women workers as well as resources for addressing workplace concerns.

In late September 2002, fifty of America’s outstanding women business leaders joined their counterparts from Finland, Lithuania, Estonia, and Russia at the Helsinki Women Business Leaders Summit. This summit provided an opportunity for participants to exchange business practices, build management skills, and develop business partnerships among Baltic Rim and American business leaders. Bonnie McElveen-Hunter, the U.S. ambassador to Finland, hosted the summit along with the U.S. embassies in Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Russia and the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Industry in Finland.

The summit featured speeches by President Tarja Talonen of Finland and President Vaira Vike-Freiberga of Latvia. The U.S. Department of State, the government of Finland, and other public and private entities sponsored the summit. In a return exchange, businesswomen from the Baltic region traveled to the United States for meetings with their U.S. colleagues and partner companies on November 11, 2002, to visit and experience firsthand how their counterparts conduct their business management styles, business skills, and the American business perspective. The U.S. visit included a two-day educational component at Georgetown University, with special events scheduled on Capitol Hill, at the White House, and at the State Department.

A week after the summit, the Schlesinger Library of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University and the National Heritage Museum in Lexington, Massachusetts, opened the exhibition “Enterprising Women: 250 Years of American Business,” which reinterprets the history of American women and of American business.

Organized into five historic sections and enhanced by interactive and evocative settings, such as an eighteenth-century print shop, a nineteenth-century dressmaking shop, and a twentieth-century beauty parlor and corporate office, “Enterprising Women” illuminates and personalizes the nation’s transformation from an agricultural and household economy to one influenced by industrialization, the rise of big business, the emergence of consumer culture, and the communications-technology revolution. Along the way, the exhibition highlights the ways in which race, class, ethnicity, geography, generation, and social upheaval infused the experiences of women in business. According to Jane Knowles, the project director for “Enterprising Women” and the acting director of the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, this exhibition is one of the most important research collections in the world on women’s history.

Women represented in this exhibition include:

“Enterprising Women” showcases women’s considerable contributions to the American success story. “Back in the 1920s when president Calvin Coolidge declared that ‘the chief business of the American people is business,’ he was not thinking about women. But women’s business has always been part of America’s business,” states Virginia Drachman, the Arthur Jr. and Lenore Stern Professor of American History at Tufts University, former Radcliffe fellow, and author of the book Enterprising Women: 250 Years of American Business, which accompanies the exhibition. “Whether they inherited or initiated their businesses, whether they marketed to women or to the general public, enterprising women have contributed to the vitality of the nation from its inception to the dawn of the twenty-first century.”

The same opening of borders and ease of communication and travel that have fostered world trade and economic development have also had serious downsides. International trafficking of women and children for forced labor and the sex industry has increased exponentially. Communities that lose out in the face of increased trade and global competition, experiencing economic distress and social breakdown, provide vulnerable and desperate victims to be preyed upon by organized criminal networks. Long a problem in East Asia and Latin America, in more recent times the post-communist societies of Eastern and Central Europe have become a hunting ground for human traffickers in the guise of emigration services, marriage bureaus, or employment agents for households or legitimate businesses.

According to the definition used by the President’s Interagency Council on Women:

Trafficking is all acts involved in the recruitment, abduction, transport, harboring, transfer, sale or receipt of persons; within national or across international borders; through force, coercion, fraud or deception; to place persons in situations of slavery or slavery-like conditions, forced labor or services, such as forced prostitution or sexual services, domestic servitude, bonded sweatshop labor or other debt bondage.

As the growing problem of trafficking in women and children was publicized by journalists and by non-governmental organizations involved in human rights, women’s issues, child welfare, and labor protection, it also became a concern of governments and international organizations. The United Nations drafted a “Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons” as a supplement to the UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. The stated purposes of the protocol are to prevent and to combat trafficking, to facilitate cooperation against trafficking, and to encourage the criminalization of trafficking activity and the protection and repatriation of its victims.

Martin J. Manning

See also: Labor Unions; World War II.

Bianchi, Suzanne M., and Daphne Spain. “Women, Work, and Family in America.” Population Bulletin 51, no. 3 (December 1996): 2–46.

Boulding, Elise. The Underside of History: A View of Women Through Time. Boulder: Westview, 1976.

Bowles, Janet K., ed. “American Feminism: New Issues for a Mature Movement.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 515 (May 1991).

Carson, Thomas, ed. Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History. Detroit: Gale Group, 1999.

Cullen-DuPont, Kathryn. Encyclopedia of Women’s History in America. New York: Facts on File, 1996.

Drachman, Virginia. Enterprising Women: 250 Years of American Business. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Families and Work Institute. Women: The New Providers: Whirlpool Foundation Study. Pt. 1. New York: Foundation, 1995.

Flexner, Eleanor. Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States. Rev. ed. Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 1975.

Frost-Knappman, Elizabeth. The ABC-CLIO Companion to Women’s Progress in America. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 1994.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. In Pursuit of Equity: Women, Men, and the Quest for Economic Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Kramarae, Cheris, and Dale Spender, eds. Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women: Global Women’s Issues and Knowledge. 3 vols. New York: Routledge, 2000.

MacDonald, Anne L. Feminine Ingenuity: Women and Invention in America. New York: Ballantine, 1992.

Spain, Daphne, and Suzanne M. Bianchi. Balancing Act: Motherhood, Marriage, and Employment Among American Women. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1996.

Tierney, Helen, ed. Women’s Studies Encyclopedia. Vol. 3, History, Philosophy, and Religion. Westport: Greenwood, 1989.

Wertheimer, Barbara M. We Were There: The Story of Working Women in America. New York: Pantheon, 1977.

Woodward, C. Vann, ed. Mary Chestnut’s Civil War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Wosk, Julie. Women and the Machine: Representations from the Spinning Wheel to the Electronic Age. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.