Large marine mammals that can weigh as much as forty tons. There are two major groups of whales: the toothed whales (suborder Odontoceti) and the toothless baleen whales (suborder Mysticeti).

Toothed whales range in length from four to sixty feet. They include the beaked and bottlenose whales (family Ziphiidae); the sperm whale, or cachalot (family Physeteridae); the beluga, or white whale; the narwhal (family Monodontidae); the river dolphins (family Platanispidae) of India and South America; and several families better known as ocean dolphins and porpoises. The killer whale and pilot whale are types of dolphin. These whales can catch fast-moving prey, such as fish or squid. They have a single blowhole and a wide throat to accommodate large prey. Many species navigate underwater using echolocation (sonar).

Baleen whales are large species, usually over thirty-three feet long. They are filter feeders, living on shrimplike krill, plankton, and small fish. They lack teeth but have brushlike sheets of a horny material called baleen, or whalebone, edging the roof of the mouth. With these strainers and their enormous tongues, they can separate tons of food from seawater. Baleen whales have narrow throats and paired blowholes.

There are three families of baleen: the right whale family (Balaenidae), including the bowhead, or Greenland whale; the gray whale family (Eschrichtidae), with a single species (Eschrichtius robustus) found in the North Pacific Ocean; and the rorqual family (Balaenopteridae), which includes the humpback whale, the sei whale, the minke whale, the Bryde’s whale, the fin whale (or common rorqual), and the blue whale, which can grow to a length of 100 feet and a weight of 150 tons.

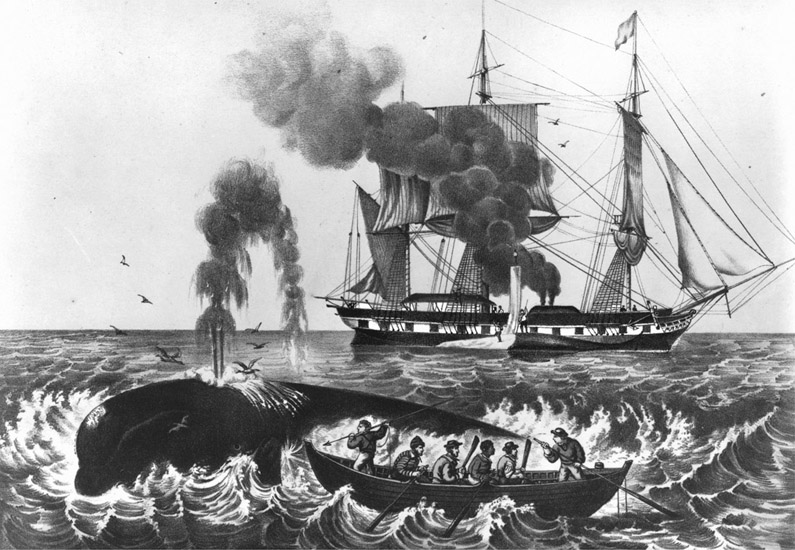

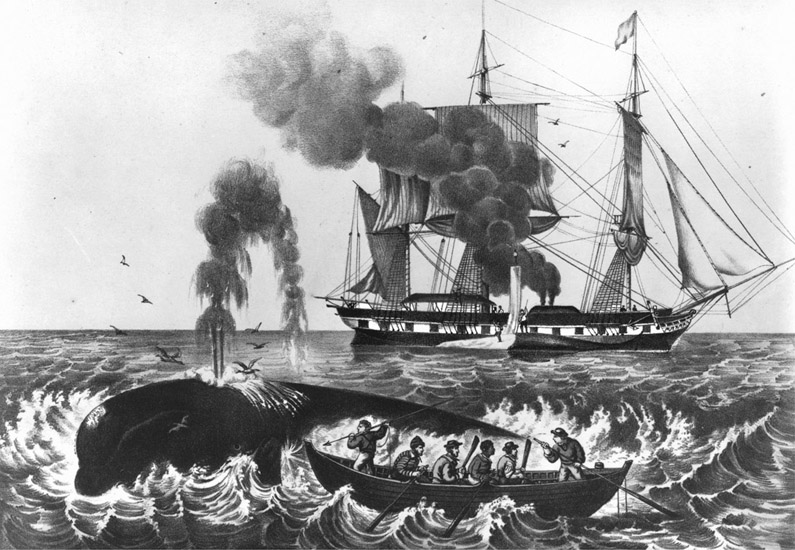

For much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, whales were hunted for commercial uses. The New England states of North America were major whaling areas during the nineteenth century. Provincetown, Massachusetts, was one of the major whaling harbors. The migratory patterns of the whales were followed, so whaling was done in the Artic and Atlantic regions, especially the Caribbean Sea, in depths that were home to a wide variety of cetacean species. During this period, New England whalers therefore sailed the Caribbean waters in search of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) and sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus). When a whale was sighted, a small boat armed with a harpoon was lowered into the water. Sailors would harpoon the whale, and after the whale was killed, it was pulled alongside the bigger craft of around 100 tons and stripped of the blubber, which was then taken on board, “tried out” in large iron pots over a hot fire on deck, and then stored in casts.

Among the products obtained from whales were sperm oil, blubber, ambergris, spermaceti, and baleen. Sperm oil is liquid wax, which comes from the blubber and from a large cavity in the head of the sperm whale. The clear liquid flows easily. It can vary in color from yellow to brownish yellow. Ambergris is a waxlike substance with a peculiar sweet odor that is produced in the intestine of the sperm whale. Because it is much lighter than water, it floats on the seas. When it washes ashore, the masses, usually weighing a couple of ounces, appear to be yellow, gray, black, or variegated. Ambergris is used as a fixative in perfumes. Spermaceti is a solid wax that is extracted from the oil. In addition to being a good lubricant, it was used in making soap. Whale oil was a major fuel before the advent of petroleum. Baleen, because it was tough and flexible, was used for corset stays, umbrella ribs, and clock springs.

Whaling was a risky business. Ships were often lost at sea as a result of hurricanes. For example, the American whaler George Osborn Knowles lost the Arizona in April 1878 and the Ellen Rizpah in August 1887 due to hurricanes. When the Arizona went down, it had on board 300 barrels of sperm oil and 40 barrels of whale oil. Knowles later launched the Carrie D. Knowles, which made sixteen successful voyages between 1887 and 1904 and secured 5,865 barrels of sperm oil before it disappeared as well.

The whale population is slowly increasing after having dipped to near-extinction as a result of overhunting. The rebound has been due largely to the work of the International Whaling Commission (IWC), the body that regulates whaling worldwide. The IWC has made the killing of suckling calves or females accompanied by calves illegal. It has also set quotas for its original fourteen member nations. Under a 1986 moratorium on commercial whaling, whales can be hunted only for the subsistence of indigenous peoples and for scientific research. The indigenous peoples of the Arctic and sub-Arctic, it is acknowledged, relied on sea mammals, especially whales, as the sole source of protein for thousands of years. In some societies today, however, whale is still in high demand and this encourages commercial hunting, something objected to by organizations such as Greenpeace. In Norway and Siberia, whale meat is often used as animal feed. In Asian countries where it is a delicacy, a little over two pounds can cost as much as $600.

Whale hunters harpoon a whale in this nineteenth-century illustration. Wide-scale hunting in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries drove many species of whales to the brink of extinction, leading to an international ban on commercial whaling in the late twentieth century. (Library of Congress)

Most of the six Caribbean countries with a vote in the IWC (Antigua and Barbuda; Belize; Dominica; Saint Kitts and Nevis; Saint Lucia; Saint Vincent and the Grenadines) have sided with Ja pan in support of continued whale hunting in exchange for economic aid. Of these countries, only Saint Vincent and the Grenadines continues whaling. The IWC has agreed on the basis of indigenous customs that harpooners on the Grenadine island of Bequia can catch no more than two humpback whales each year.

Since the decline of whale hunting, whale watching has been growing as a major industry. The industry now earns about $1 billion annually. Close to 9 million people in nearly 90 countries whale watch annually from boats or on land.

Cleve McD. Scott

See also: Oil.

Bibliography

Currie, Stephen. Thar She Blows: American Whaling in the Nineteenth Century. Minneapolis: Lerner, 2001.

Faiella, Graham. Whales. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 2002.