The first step in becoming an Excel VBA programmer is to become familiar with the environment in which Excel VBA programming is done. Each of the main Office applications has a programming environment referred to as its Integrated Development Environment (IDE). Microsoft also refers to this programming environment as the Visual Basic Editor.

Our plan in this chapter and Chapter 4 is to describe the major components of the Excel IDE. We realize that you are probably anxious to get to some actual programming, but it is necessary to gain some familiarity with the IDE before you can use it. Nevertheless, you may want to read quickly through this chapter and the next and then refer back to them as needed.

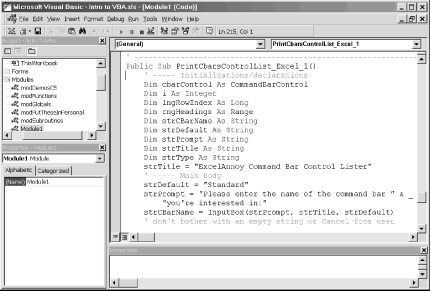

In Office 97, the Word, Excel, and PowerPoint IDEs have the same appearance, shown in Figure 3-1. (Beginning with Office 2000, Microsoft Access also uses this IDE.) To start the Excel IDE, simply choose Visual Basic Editor from the Macros submenu of the Tools menu, or hit Alt-F11.

Let us take a look at some of the components of this IDE.

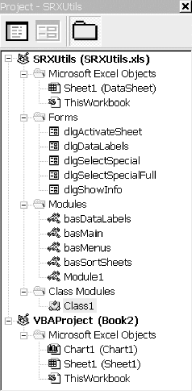

The window in the upper-left corner of the client area (below the toolbar) is called the Project Explorer. Figure 3-2 shows a close-up of this window.

Note that the Project Explorer has a treelike structure, similar to the Windows Explorer's folders pane (the left-hand pane). Each entry in the Project Explorer is called a node . The top nodes, of which there are two in Figure 3-2, represent the currently open Excel VBA projects (hence the name Project Explorer). The view of each project can be expanded or contracted by clicking on the small boxes (just as with Windows Explorer). Note that there is one project for each currently open Excel workbook.

Each project has a name, which the programmer can choose. The default name for a project is VBAProject. The top node for each project is labeled:

ProjectName(WorkbookName)

where ProjectName is the name of the

project and WorkbookName is the name of

the Excel workbook.

At the level immediately below the top (project) level, as Figure 3-2 shows, there are nodes named:

| Microsoft Excel Objects |

| Forms |

| Modules |

| Classes |

Under the Microsoft Excel Objects node, there is a node for each worksheet and chartsheet in the workbook, as well as a special node called ThisWorkbook, which represents the workbook itself. These nodes provide access to the code windows for each of these objects, where we can write our code.

Under the Forms node, there is a node for each form in the project. Forms are also called UserForms or custom dialog boxes. We will discuss UserForms later in this chapter.

Under the Modules node, there is a node for each code module in the project. Code modules are also called standard modules. We will discuss modules later in this chapter.

Under the Classes node, there is a node for each class module in the project. We will discuss classes later in this chapter.

The main purpose of the Project Explorer is to allow us to navigate around the project. Worksheets and UserForms have two components—a visible component (a worksheet or dialog) and a code component. By right-clicking on a worksheet or UserForm node, we can choose to view the object itself or the code component for that object. Standard modules and class modules have only a code component, which we can view by double-clicking on the corresponding node.

Let us take a closer look at the various components of an Excel project.

Under each node in the Project Explorer labeled Microsoft Excel Objects is a node labeled ThisWorkbook. This node represents the project's workbook, along with the code component (also called a code module) that stores event code for the workbook. (We can also place independent procedures in the code component of a workbook module, but these are generally placed in a standard module, discussed later in this chapter.)

Simply put, the purpose of events is to allow the VBA programmer to write code that will execute whenever one of these events fires. Excel recognizes 21 events related to workbooks. We will discuss these events in Chapter 11; you can take a quick peek at this chapter now if you are curious. Some examples:

The Open event, which occurs when the workbook is opened.

The BeforeClose event, which occurs just before the workbook is closed.

The NewSheet event, which occurs when a new worksheet is added to the workbook.

The BeforePrint event, which occurs just before the workbook or anything in it is printed.

Under each Microsoft Excel Objects node in the Project Explorer is a node for each sheet. (A sheet is a worksheet or a chartsheet.) Each sheet node represents a worksheet or chartsheet's visible component, along with the code component (also called a code module) that stores event code for the sheet. We can also place independent procedures in the code component of a sheet module, but these are generally placed in a standard module, discussed next.

Excel recognizes 8 events related to worksheets and 13 events related to chartsheets. We will discuss these events in Chapter 11.

A module, also more clearly referred to as a standard module , is a code module that contains general procedures (functions and subroutines). These procedures may be macros designed to be run by the user, or they may be support programs used by other programs. (Remember our discussion of modular programming.)

Class modules are code modules that contain code related to custom objects. As we will see, the Excel object model has a great many built-in objects (almost 200), such as workbook objects, worksheet objects, chart objects, font objects, and so on. It is also possible to create custom objects and endow them with various properties. To do so, we would place the appropriate code within a class module.

However, since creating custom objects is beyond the scope of this book, we will not be using class modules. (For an introduction to object-oriented programming using VB, allow me to suggest my book, Concepts of Object-Oriented Programming with Visual Basic, published by Springer-Verlag, New York.)

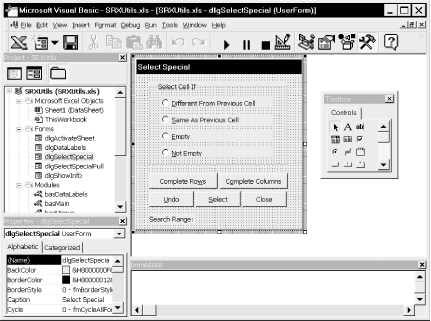

As you no doubt know, Excel contains a great many built-in dialog boxes. It is also possible to create custom dialog boxes, also called forms or UserForms. This is done by creating UserForm objects. Figure 3-3 shows the design environment for the Select Special UserForm that we mentioned in Chapter 1.

The large window on the upper-center in Figure 3-3 contains the custom dialog box (named dlgSelectSpecial) in its design mode. There is a floating Toolbox window on the right that contains icons for various Windows controls.

To place a control on the dialog box, simply click on the icon in the Toolbox and then drag and size a rectangle on the dialog box. This rectangle is replaced by the control of the same size as the rectangle. The properties of the UserForm object or of any controls on the form can be changed by selecting the object and making the changes in the Properties window, which we discuss in the next section.

In addition to the form itself and its controls, a UserForm object

contains code that the VBA programmer writes in support of these

objects. For instance, a command button has a Click event that fires

when the user clicks on the button. If we place such a button on the

form, then we must write the code that is run when the Click event

fires; otherwise, clicking the button does nothing. For instance, the

following is the code for the Close button's Click

event in Figure 3-3. Note that the Name property of

the command button has been set to

cmdClose :

Private Sub cmdClose_Click() Unload Me End Sub

All this code does is unload the form.

Along with event code for a form and its controls, we can also include support procedures within the UserForm object.

Don't worry if all this seems rather vague now. We will devote an entire chapter to creating custom dialog boxes (that is, UserForm objects) later in the book and see several real-life examples throughout the book.