As witness to the importance of the Range object, there are a total of 113 members (properties and methods) throughout the Excel object model that return a Range object. This number drops to 51 if we count only distinct member names, as shown in Table 19-2. (For instance, BottomRightCell is a property of 21 different objects, as is TopLeftCell.)

Table 19-2. Excel Members That Return a Range Object

|

_Default |

End |

Range |

|

ActiveCell |

EntireColumn |

RangeSelection |

|

BottomRightCell |

EntireRow |

RefersToRange |

|

Cells |

Find |

Resize |

|

ChangingCells |

FindNext |

ResultRange |

|

CircularReference |

FindPrevious |

RowDifferences |

|

ColumnDifferences |

GetPivotData |

RowRange |

|

ColumnRange |

Intersect |

Rows |

|

Columns |

Item |

SourceRange |

|

CurrentArray |

LabelRange |

SpecialCells |

|

CurrentRegion |

Location |

TableRange1 |

|

DataBodyRange |

MergeArea |

TableRange2 |

|

DataLabelRange |

Next |

ThisCell |

|

DataRange |

Offset |

TopLeftCell |

|

Dependents |

PageRange |

Union |

|

Destination |

PageRangeCells |

UsedRange |

|

DirectDependents |

Precedents |

VisibleRange |

|

DirectPrecedents |

Previous |

Let us take a look at some of the more prominent ways to define a Range object.

The Range property applies to the Application, Range, and Worksheet objects. Note that:

Application.Range

is equivalent to:

ActiveSheet.Range

When Range is used without qualification within the code module of a worksheet, then it is applied to that sheet. When Range is used without qualification in a code module for a workbook, then it applies to the active worksheet in that workbook.

Thus, for example, if the following code appears in the code module for Sheet2:

Worksheets(1).Activate

Range("D1").Value = "test"then its execution first activates Sheet1, but still places the word "test" in cell D1 of Sheet2. Because this makes code difficult to read, I suggest that you always qualify your use of the Range property.

The Range property has two distinct syntaxes. The first syntax is:

object.Range(Name)

where Name is the name of the range. It

must be an A1-style reference and can include the range operator (a

colon), the intersection operator (a space), or the union operator (a

comma). Any dollar signs in Name are

ignored. We can also use the name of a named range.

To illustrate, here are some examples:

Range("A2")

Range("A2:B3")

Range("A2:F3 A1:D5") ' An intersection

Range("A2:F3, A1:D5") ' A unionOf course, we can use the ConvertFormula method to convert a formula from R1C1 style to A1 style before applying the Range property, as in:

Range(Application.ConvertFormula("R2C5:R6C9", xlR1C1, xlA1))Finally, if TestRange is the name of a range, then

we may write:

Range(Application.Names("TestRange"))or:

Range(Application.Names!TestRange)

to return this range.

The second syntax for the Range property is:

object.Range(Cell1,Cell2)

Here Cell1 is the cell in the upper-left

corner of the range and Cell2 is the cell

in the lower-right corner, as in:

Range("D4", "F8")Alternatively, Cell1 and

Cell2 can be Range objects that represent

a row or column. For instance, the following returns the Range object

that represents the second and third rows of the active sheet:

Range(Rows(2), Rows(3))

It is important to note that when the Range property is applied to a

Range object, all references are relative to the upper-left corner

cell in that range. For instance, if rng

represents the second column in the active sheet, then:

rng.Range("A2")is the second cell in that column, and not cell A2 of the worksheet. Also, the expression:

rng.Range("B2")represents the (absolute) cell C2, because this cell is in the second

column and second row from cell B1 (which is the upper-left cell

in the range rng ).

The Excel object model does not have an official Cells collection nor

a Cell object. Nevertheless, the cells property acts as though it

returns such a collection as a Range object. For instance, the

following code returns 8:

Range("A1:B4").Cells.CountIncidentally, Cells.Count returns

16,777,216

=

256

*

65536.

The Cells property applies to the Application, Range, and Worksheet objects (and is global). When applied to the Worksheet object, it returns the Range object that represents all of the cells on the worksheet. Moreover, the following are equivalent:

Cells Application.Cells ActiveSheet.Cells

When applied to a Range object, the Cells property simply returns the same object, and hence does nothing.

The syntax:

Cells(i,j)

returns the Range object representing the cell at row

i and column j.

Thus, for instance:

Cells(1,1)

is equivalent to:

Range("A1")One advantage of the Cells property over the Range method is that the Cells property can accept integer variables. For instance, the following code searches the first 100 rows of column 4 for the first cell containing the word "test." If such a cell is found, it is selected. If not, a message is displayed:

Dim r As Long

For r = 1 To 100

If Cells(r, 4).Value = "test" Then

Cells(r, 4).Select

Exit For

End If

Next

If r = 101 then MsgBox "No such cell."It is also possible to combine the Range and Cells properties in a useful way. For example, consider the following code:

Dim r As Long

Dim rng As Range

With ActiveSheet

For r = 1 To 100

If Cells(r, r).Value <> "" Then

Set rng = .Range(.Cells(1, 1), .Cells(r, r))

Exit For

End If

Next

End With

rng.SelectThis code searches the diagonal cells (cells with the same row and

column number) until it finds a nonempty cell. It then sets

rng to refer to the range consisting of the

rectangle whose upper-left corner is cell A1 and whose lower-right

corner is the cell found in this search.

The Excel object model does not have an official Columns or Rows collection. However, the Columns property does return a collection of Range objects, each of which represents a column. Thus:

ActiveSheet.Columns(i)

is the Range object that refers to the ith

column of the active worksheet (and is a collection of the cells in

that column). Similarly:

ActiveSheet.Rows(i)

refers to the ith row of the active

worksheet.

The Columns and Rows properties can also be used with a Range object.

Perhaps the simplest way to think of rng.Columns

is as the collection of all columns in the worksheet

reindexed so that column 1 is the leftmost

column that intersects the range rng. To

support this statement, consider the following code, whose results

are shown in Figure 19-1:

Dim i As Integer

Dim rng As Range

Set rng = Range("D1:E1, G1:I1")

rng.Select

MsgBox "First column in range is " & rng.Column ' Displays 4

MsgBox "Column count is " & rng.Columns.Count ' Displays 2

For i = -(rng.Column - 2) To rng.Columns.Count + 1

rng.Columns(i).Cells(1, 1).Value = i

NextNote that the range rng is selected in

Figure 19-1 (and includes cell D1). The Column

property of a Range object returns the leftmost column that

intersects the range. (Similarly, the Row property returns the

topmost row that intersects the range.) Hence, the first message box

will display the number 4.

Now, from the point of view of rng,

Columns(1) is column number 4 of the worksheet

(column D). Hence, Columns(0) is column number 3

of the worksheet (column C) which, incidentally, is not part of

rng. Indeed, the first column of the

worksheet is column number

-(rng.Column - 2)

which is precisely why we started the For loop at

this value.

Next, observe that:

rng.Columns.Count

is equal to 2 (which is the number displayed by the second message

box). This is a bit unexpected. However, for some reason, Microsoft

designed the Count property of r

ng

.Columns to return the number of

columns that intersect only the leftmost area in

the range, which is area D1:E1. (We will discuss areas a bit later.)

Finally, note that:

rng.Columns(3)

is column F, which does not intersect the range at all.

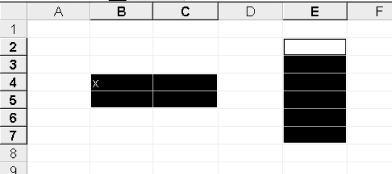

As another illustration, consider the range selected in Figure 19-2. This range is the union B4:C5, E2:E7.

The code:

Dim rng As Range

Set rng = Range("B4:C5, E2:E7")

MsgBox rng.Columns(1).Cells(1, 1).Valuedisplays a message box containing the x shown in

cell B4 in Figure 19-2 because the indexes in the

Cells property are taken relative to the upper cell in the leftmost

area in the range.

Note that we can use either integers or characters (in quotes) to denote a column, as in:

Columns(5)

and:

Columns("E")We can also write, for instance:

Columns("A:D")to denote columns A through D. Similarly, we can denote multiple rows as in:

Rows("1:3")Since a syntax such as:

Columns("C:D", "G:H")does not work, the Union method is often useful in connection with the Columns and Rows methods. For instance, the code:

Dim rng As Range Set rng = Union(Rows(3), Rows(5), Rows(7)) rng.Select

selects the third, fifth, and seventh rows of the worksheet containing this code or of the active worksheet if this code is in a workbook or standard code module.

The Offset property is used to return a range that is offset from a given range by a certain number of rows and/or columns. The syntax is:

RangeObject.Offset(RowOffset,ColumnOffset)

where RowOffset is the number of rows and

ColumnOffset is the number of columns by

which the range is to be offset. Note that both of these parameters

are optional with default value 0, and both can be either positive,

negative, or 0.

For instance, the following code searches the first 100 cells to the immediate right of cell D2 for an empty cell (if you tire of the message boxes, simply press Ctrl-Break to halt macro execution):

Dim rng As Range

Dim i As Integer

Set rng = Range("D2")

For i = 1 To 100

If rng.Offset(0, i).Value = "" Then

MsgBox "Found empty cell at offset " & i & " from cell D2"

End If

Next