Walking

Taking a group for a walk allows the leader to involve all the group participants in some way, from initial route planning to navigation while outdoors. A ‘walk’ may be a short excursion or a multi-day expedition. The art of good leadership rests on the ability to delegate and co-ordinate, rather than doing; this applies as much to adventure learning instructors entrusting tasks and responsibilities to participants as it does to leaders of a team of workers. This allows the leader to retain oversight of what is happening and to ensure that every task is completed, rather than becoming locked into one element and distracted from their overall responsibilities.

There are different types of land where groups may walk:

- • Urban streets and parks, with clearly defined features and facilities close by.

- • Lowland territory, with well-defined tracks and easily identifiable features, relatively close to public services (roads, telephones).

- • Moorland, heath and hills, which are more remote, carrying therefore greater risks because of the greater inaccessibility, fewer features and distant access to services and facilities.

Problems can occur even when in the middle of a city; in fact, the risks are arguably greater here because the instructor can be fooled into assuming that the close proximity to facilities and services equates to a relatively safer environment. The essential criteria when out walking are founded on common sense:

- • Check frequently that the group is together; with less challenging terrain come greater distractions and more areas where participants may be inclined to walk away on their own.

- • Be aware of individual problems, such as blisters, tiredness, cold and hunger; these can develop into bigger problems if unattended. Participants not used to walking far may not realise they are becoming fatigued or a sore ‘hot spot’ is becoming a blister.

- • Details should be left with someone at a ‘base’ with a landline telephone and they should be informed when the group has returned. It should not be assumed that mobile telephones would work, even in an urban environment, so the safety contact should have an estimated time of return and there should be an agreed process of what to do if they have not heard from the instructor by this time.

- • Be mindful of the environment and property. This applies to the manner in which the participants behave in respect of the members of the public and the environment in which they are out walking but also the potential interaction of members of the public with the group. In the modern world, the threat that unknown strangers can pose to children, young people and vulnerable adults cannot be underestimated and the activity briefing should cover a process for unsolicited encounters, as well as warning participants of the need to keep their possessions safe.

The Countryside Code is a set of rules that apply to all regions of the United Kingdom, although aimed specifically at rural, particularly agricultural, areas. Whatever the environment, the rules can be presented and discussed with participants as a part of heading outdoors; put simply, they are ‘respect, protect and enjoy’:

- • Respect other people: consider how actions affect others, such as the entire group spreading across a footpath so others cannot get by, leave gates and property as they are and follow footpaths.

- • Protect the natural environment: ‘leave nothing but footprints, take nothing but photographs’; once the participants have left there should be no trace of them left behind.

- • Enjoy the outdoors: plan and be prepared for weather changes, follow local signs.

A part of planning is to plan the route that will be followed, which is something that can involve all participants. The first step is to work out the route the group will follow. All areas in which an adventure learning instructor will be operating will be covered by a map, the commonest being an Ordnance Survey map, making route planning an valuable exercise in geography and mathematics as participants work out distance, pacing, timing and direction, as well as the description of the route they will follow.

Scale

A map is a drawing of an area of land to a pre-determined scale, which is the amount by which you would have to enlarge the map to get it as big as the ground it is demonstrating. Every map has a scale printed on the front and you should always check this figure before you start. Although maps may be drawn to any scale, the most commonly operated two scales are known as ‘one to twenty-five thousand’ and ‘one to fifty thousand’:

- • 1:25,000 means 1 centimetre = 250 metres on the ground (or 4 centimetres = 1 kilometre)

- • 1:50,000 means 1 centimetre = 500 metres on the ground (or 2 centimetres = 1 kilometre)

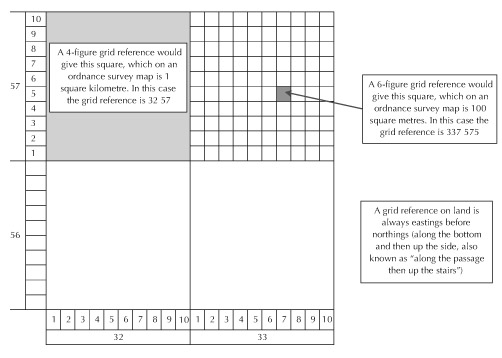

The grid lines on an Ordnance Survey map are called eastings (those going east to west, with the scale along the bottom) and northings (those going north to south with the scale up the side), which are used to locate a place within the square. Each square represents a kilometre and has grid reference, which is found by putting together the numbers of the easting and northing that cross in its bottom left hand corner (four-figure grid reference); the saying to remember it is ‘go along the passage, then up the stairs’. Each square is sub-divided into tenths and a place can be more accurately identified by adding the tenth to the grid reference and pinpointing a location within the square (a six-figure grid reference); further accuracy can be achieved by sub-dividing the tenths further into tenths again (an eight-figure grid reference).

Figure 20

Four- and six-figure grid references

Contour lines

Down the side of a map are the symbols and other useful information to aid in route planning and interpreting the map to the ground. There are lines on a map that show the height of the land, called contour lines; they join together places of the same height and form patterns to show valleys, hills and flat land. The closer together the contour lines appear, the steeper the land on the ground. The numbers that appear on the contour lines show the height above sea level and face uphill (the top of the number is the uphill side). Similarly, the writing on a map is always to the north (the top of the writing is the north side).

Direction

When in the outdoors, direction is found using a map and compass. People happily say that a compass points north but there are in fact three ‘norths’: grid north, true north and magnetic north! Grid north refers to the direction northwards along the grid lines of a map projection and is related to the way in which the spherical earth is represented on a flat piece of paper. True north is the North Pole, the axis on which the earth rotates.

Magnetic north is the place where the earth’s magnetic field points directly downwards. Maps are oriented to grid north, whereas a compass will point to magnetic north. The magnetised needle on the compass aligns with the earth’s magnetic field and is drawn to magnetic north; this north moves very slowly and continually because of the movement of the earth’s magnetic core, so the variation between grid and magnetic north is shown on the side of the map.

When converting from the map to a bearing, the variation is added (‘grid to mag: add’) and when taking a bearing and putting this onto the map, it is subtracted (‘mag to grid: get rid’).

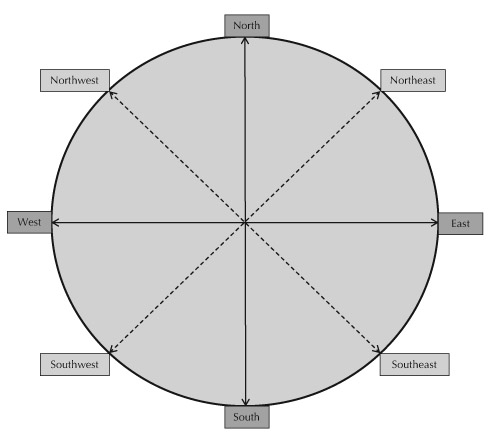

A bearing is simply the angle calculated from one point to another, relative to north. Imagine a circle, with north at the top; there are 360 degrees in a circle, so north would be at zero or 360 degrees. From this point, the cardinal points indicate east (90 degrees), south (180 degrees) and west (270 degrees) and the intercardinal points are the intermediate points that show northeast (45 degrees), southeast (135 degrees), southwest (225 degrees) and northwest (315 degrees).

Figure 21

The cardinal and intercardinal points of a compass

There are three arrows on a land compass:

- • The big arrow on the top is known as the direction-of-travel arrow.

- • The arrow in the middle of the compass with a red end that points north; never follow this arrow, because it only points north!

- • The arrow marked on the dial that matches up with the red and white arrow (the orienting arrow); where this touches the dial indicates the number of degrees (the bearing).

Figure 22

Basic land compass components

When using a compass, make sure it is away from metal or magnetic objects, as this will attract the arrow and distort the reading.

To take a bearing from the map, line up the long edge of the compass between the two points, with the direction-of-travel arrow pointing to the destination. Turn the dial in the middle of the compass so that the parallel north/south orienting lines in the centre are lined up parallel to the grid lines. Finally, read the number of degrees (the bearing) and adjust for magnetic variation. In order to move in the right direction, hold the compass and turn until the magnetic north needle points in the same direction as the orienting arrow; the direction-of-travel arrow is now pointing in the direction to walk.

The compass must be used continually throughout the walk to stay on track; to make navigation easier divide the route into short sections and use landmarks and features as a ‘tick list’ that you can use to confirm you are on route.

To convert a bearing from the ground to the map, point the direction-of-travel arrow at a feature on the ground (a hill, a church spire), line up the orienting arrow with the north arrow and read off the bearing from the direction-of-travel arrow, make the adjustment for magnetic variation and then place the compass on the map with the direction-of-travel arrow pointing at the feature. Line up the parallel orienting lines with the grid lines on the map and your position is somewhere on that line along the side of the compass. By doing this for two or more features, you can triangulate where you are.

Distance

It’s very rare that a route will follow a straight line between two points on the map; roads, rivers and footpaths all have curves and bend around features like woodland, so it can appear tricky to measure the distance travelled. Commercial map measurers are available to buy, but two simple ways of measuring distance are with string or with a piece of paper and the scale marker down the side of the map.

- • Place one end of a length of string on the starting point and carefully follow the route on the map, laying the string along the footpaths and following curves as closely as possible. If the string is longer than the route, the end point can be marked on the string with a pen; if the route is longer than the string, the exercise can be undertaken as many times as necessary and the distances added together to find the total. The straightened piece of string is laid along the scale bar to measure the distance of the route.

- • Using a piece of paper and starting at one corner, pivot the paper so that the edge follows the route, marking every bend and turn on the paper until the end of the route. The piece of paper can be laid against the scale bar to measure the distance of the route.

Timing

Once the participants know the route they intend to follow, they need to work out the time that they expect it to take them. This is obviously not going to be accurate to the minute, but will provide a guide both for the participants and for the safety person, who will contact the emergency services if the group is not back at the time expected. The average walking speed is estimated at 5 kilometres per hour (12 minutes per kilometre), although this will vary according to the group ability, what they are carrying and what they are doing along the way. It takes longer to walk uphill and therefore it is usual to add one minute for every ten metres of height climbed (known as ‘Naismith’s rule’). Contour lines appear at 5-metre intervals on a 1:25,000 scale map and at 10 metres intervals on a 1:50,000 scale map.

Another way of calculating distance travelled is to count paces; mark out a one hundred metre line and have the participants work out their average pace per 100 metres (how many double paces they take to one hundred metres). Then while out on the walk, the young people can see how their pacing compares to the terrain they are traversing.

When transferring the planned route and timings, it is essential to add in any time for rest stops and activities along the way so that a reasonable estimation of the duration for the walk can be calculated and provided to the safety person, as well as to the parents or carers who may be collecting the participants at the end.

While out walking, participants can collect and record a set list of items, they can undertake a survey (for example of people they meet, of flora and fauna) or they can take pictures and make up a photomosaic of an area (which works really well with macrophotography).