My Tradition outlaws narcotics. It had always been understood that ‘men of honor’ don't deal in narcotics.

—Joseph Bonanno, A Man of Honor (1983)

Salvatore Lucania knew an opportunity when he saw one. He lined his pockets with heroin and morphine, and set out to work the Lower East Side. It was spring 1916. America had just declared its first war on drugs. When doctors stopped writing prescriptions for heroin, addicts filled the streets, desperate for new suppliers. Lucania would later say that he knew what “them kind of addicts looked like.” Approaching junkies, he “told them I had some.” After a string of deals, Lucania was arrested on East 14th Street for peddling to “a dope fiend.” He was convicted and spent six months in the reformatory. But prison did not reform him. In June 1923, Lucania sold heroin to an informant for federal narcotics agents. To save himself, he tipped off the agents to a trunk of narcotics at 163 Mulberry Street in Little Italy.1

Lucania spent the next decade scheming his way through Prohibition. He soon traded the streets for a suite at the Waldorf-Astoria, where he ran his operations as “Charles Ross.” But “Charles Ross” would become better known as Mafia boss Charles “Lucky” Luciano.2

Luciano's drug record did not slow his rise to the top. Even when he was a boss, Luciano kept narcotics traffickers among his closest associates. This has been all but forgotten. Today, Luciano is lionized as the purported architect of the Cosa Nostra. Time named Luciano as one of its “100 Persons of the Century.” When Luciano's drug record is discussed at all, it is usually dismissed as a youthful indiscretion, or as a sign of his disrespect for Mafia tradition.3 It is never considered a reflection of the Mafia itself.

The first question for this chapter then is: How has the Mafia obscured its role in America's drug trade? The chapter examines the Mafia mythology on drugs. The second, bigger question is: What was its actual relationship to the narcotics trade? The chapter uses facts to peel back the myths.4

THE DRUGS SCENE FROM THE GODFATHER

It is one of the most evocative scenes from The Godfather. The dons from around the country are assembled around a dark table. They have come to resolve whether the Mafia will enter the drug trade. The younger dons push the aging Don Vito Corleone of New York (played by the great Marlon Brando) to give his approval. He warns them against it:

I believe this drug business—is gonna destroy us in the years to come. I mean, it's not like gambling or liquor—even women—which is something that most people want nowadays, and is, ah, forbidden to them by the pezzonovante of the Church. Even the police departments that've helped us in the past with gambling and other things are gonna refuse to help us when it comes to narcotics.

The traditional Don Corleone, however, is outnumbered by his greedier colleagues. Don Zaluchi of Detroit rises to present the pro-drug rationale:

I also don't believe in drugs. For years I paid my people extra so they wouldn't do that kind of business. Somebody comes to them and says, “I have powders; if you put up three, four thousand dollar investment—we can make fifty thousand distributing.” So they can't resist.

Zaluchi proposes a compromise:

I want to control it as a business, to keep it respectable….

BAM! [slamming his hand on the table]:

I don't want it near schools—I don't want it sold to children! That's an infamia. In my city, we would keep the traffic in the dark people—the colored. They're animals anyway, so let them lose their souls.

Don Barzini of Brooklyn sums up their resolution, “Traffic in drugs will be permitted, but controlled.” In the end, though, Don Corleone prevails by killing his greedy, racist rivals.5

This iconic scene from the 1972 masterpiece planted indelible images. When a young Sammy “The Bull” Gravano saw it, it reflected his ideal beliefs in the Cosa Nostra. “It was basically the way I saw the life. Where there was some honor. Like when Don Corleone, Marlon Brando, says about the drugs, sure, he owned these people, but he would lose them with that,” said Gravano.6 Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola were drawing on Mafia mythology on drugs when they created this scene. The three major myths are crystalized in it.

The Myth of a Traditional Ban

The Mafia first denied having anything to do with drugs as a matter of tradition. Its members may have been bootleggers and bookies, but not dope pushers. In The Godfather, this myth is embodied in the character of Don Corleone, the traditional mafioso who stands against drugs. We can call this the myth of a traditional ban.

Mafiosi have long declared that they stayed out of drugs. In his bestselling autobiography A Man of Honor, Mafia boss Joseph Bonanno asserted, “My Tradition outlaws narcotics. It had always been understood that ‘men of honor’ don't deal in narcotics.” Bonanno claimed that he “did not tolerate any dealings in prostitution or narcotics.”7 When Frank Costello was under investigation in 1946, he held a press conference and declared, “I detest the narcotic racket and anyone connected with it. To my mind there is no one lower than a person dealing in it. It is low and filthy-trading on human misery.” Similarly, when Thomas Lucchese testified before the New York State Crime Commission in 1952, he “reserved his real indignation” for drug traffickers. “Any man who got a family should die before he goes into any of that kind of business,” Lucchese insisted.8

The Myth of Generational Decline

As the drug convictions mounted, the families tried to blame it all on low-level, young button men. In The Godfather, this myth is articulated by Don Zaluchi, who laments that his soldiers were succumbing to drug money. We can call this the myth of generational decline.

Joe Bonanno argued that “the lure of high profits had tempted some underlings to freelance in the narcotics trade.” He suggested this was due to a generational decline. “It reflected how much ground our Traditional values had lost,” said Bonanno. His son, Bill Bonanno, echoed his father's sentiments, saying, “The ultimate prospect of big profits far outweighed the lingering attraction of old traditions—at least in the minds of newer leaders who were coming up through the Families.”9 Angelo Lonardo, a former underboss in Cleveland, struck similar themes in his testimony before a Senate Committee in 1988:

It has changed since I first joined in the 1940s, and, especially, in the last few years with the growth of narcotics. Greed is causing younger members to go into narcotics without the knowledge of the Families. These younger members lack the discipline and respect that made “This Thing” as strong as it once was.

When asked about the timing of this shift, Lonardo pinned it on “the late sixties or seventies.” Ironically, Lonardo himself was a convicted narcotics trafficker.10

The Myth of Control

Others have rationalized away the Mafia's involvement in narcotics by suggesting that at least the mob controlled the drug trade as a business. This myth is articulated by Don Zaluchi (“I want to control it as a business, to keep it respectable”), and Don Barzini (“Traffic in drugs will be permitted, but controlled”). The image of a grand conclave of the Mafia deciding the future of the drug trade suggests omnipotent power. We can call this the myth of control.

Writers have portrayed the entire drug trade as being controlled by a few, all-powerful mafiosi. In Martin Gosch and Richard Hammer's fictionalized “memoirs” of Lucky Luciano, The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano, Luciano purportedly makes an offer to the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) to “shut off the supply to America.”11 Joe Bonanno blamed the police's foiling of the Mafia's 1957 conference in Apalachin, New York, for stymieing a mob ban on narcotics. “If the 1957 meeting had gone according to plan there no doubt would have been a reaffirmation of our Tradition's opposition to narcotics,” claimed Bonanno.12 As we will see, politicians have contributed to this myth by blaming the entire drug trade on a single person or mob conclave.

THE HISTORICAL RECORD OF THE MAFIA AND DRUGS

Almost nothing about the Mafia mythology on drugs is true. There was no longstanding “tradition” against drug dealing. Mafiosi were involved in illegal narcotics almost from the beginning. Nor was the trafficking confined to younger, low-level underlings. And contrary to the myth of control, the drug trade was messy and haphazard. Ultimately, the Mafia flooded New York City and the country with narcotics. This is how they did it.

When Narcotics Were Legal, 1890–1914

When Leroy Street needed a fix, he went to the pharmacist on Avenue B who sold him heroin manufactured by Bayer of Germany. Bayer's heroin was so pure that Leroy had to dilute it with milk sugar before injecting it into his vein. “There was one drugstore that gave us Christmas presents,” Street remembered. “It was really something: a brand-new, shining hypodermic needle with a little ribbon around it and a little card, ‘Merry Christmas.’”13

New York City was an addict's paradise; drugs were cheap, easy, and everywhere. Without state or federal restrictions on heroin or cocaine, many “medicines” were little more than bottles of opiates. Coca-Cola put cocaine in its soda until 1903. And it was all legal.14

Narcotics were, in fact, legal throughout most of the Mafia's early existence. As a British official observed, through World War I “the supply of drugs for purposes of abuse…was in most countries not actually illegal.”15 The New York State legislature did not enact its first laws against cocaine and heroin trafficking until 1913–1914, and the US Congress did not do so until the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914. Even then, the importation of heroin into the United States was not banned completely until 1924.16 Meanwhile, Italy did not pass its first narcotics law until 1923, a weak law with a maximum penalty of six months.17

The Mafia could not have had a longstanding “tradition” against illegal narcotics trafficking because there was no such thing. When Joe Bonanno waxes on that “it had always been understood that ‘men of honor’ don't deal in narcotics,” we have to wonder whether his memories were clouded by nostalgia or intentional misdirection. Bonanno was eighteen years old before narcotics were made illegal in his native Italy. Bayer was lawfully supplying the world with heroin. So if there was some virgin era when the Mafia eschewed drug dealing, it was practically meaningless. We should dispense with the myth of tradition.

THE DAWN OF THE DRUG PROHIBITION, 1915–1939

Drug prohibition made New York City the center of the transatlantic drug trade. Enormous amounts of narcotics flowed through the Port of New York in the 1920s and ’30s. Smugglers didn't move kilos; they moved tons. Around Christmas 1928, a ton of narcotics was found in packing cases labeled as brushes. In April 1931, agents confiscated three tons of narcotics from a liner docked on the Chelsea piers. The Elias and George Eliopoulos brothers reputedly only sold narcotics in lots of a hundred kilos or more.18

Although traffickers of every ethnicity engaged in the drug trade, Jewish gangsters initially led the trade in New York. Arnold Rothstein was the most significant trafficker in the 1920s, though he probably never touched an ounce of heroin himself. After Rothstein was shot in the Park Central Hotel in 1928, investigators found in his safe deposit boxes the financial records of his drug smuggling. (True to myth, Rothstein's widow claimed her husband's attitude to narcotics was “one of repugnance.”)19 His deputies Irving Sobel and Yasha Katzenberg had organized new smuggling routes from Europe and Southeast Asia. The racketeer Louis “Lepke” Buchalter meanwhile had a morphine plant in the Bronx.20

Italian drug syndicates followed closely behind the Jewish traffickers. In the 1910s, the New York Kehillah, a Jewish community organization, hired a private investigator to report on criminal activities. When the historian Alan Block analyzed the reports on drug trafficking, he found that after Jews (31 percent), the Italians were the second largest ethnic group in the cocaine trade (8 percent), and they were the only other group that formed drug syndicates. Jews and Italians often worked in combinations in a market that was “fragmented, kaleidoscopic and sprawling.”21

The emergence of Italian drug syndicates is confirmed by other sources as well. Prosecutions of the Brooklyn-based Camorra (mainland Italy's counterpart to the Sicilian Mafia) revealed that the Camorristas were heavily involved in cocaine dealing in the 1910s.22 A 1917 report on drug trafficking found that “‘Little Italy,’ in east Harlem, is perhaps as large a market as any.” Leroy Street, the addict who lived through the dawn of the drug war, confirms an early Italian presence: “The Italians were involved in the beginning,” he recalled.23

Italian syndicates gradually surpassed Jewish gangsters as the dominant wholesalers in the 1930s. Both dealers and users witnessed this trend. “I was pushed out by the Italians about ’38, ’39, before the war,” remembered Charlie, an independent Italian-American dealer. “Before that—the Jews had the drugs.” Jack, a street dealer, saw Italian traffickers grow in influence in the ’30s. “But it wasn't overnight you know…infiltration was gradual,” said Jack. For Eddie, “Harlem was the main place. I'd buy from guys in the street. They were Italian, all Italian—the ones I knew anyhow,” he remembered. African-American dealers also report a takeover by Italian syndicates in the ’30s. “Who really controlled it was the bigger people on the East Side, the Sicilians…in the twenties the Jewish people had it,” recalled Curtis, a black dealer in Harlem. As a seller named Mel recounted, “When I started dealing I had Chinese and Jewish connections; later I had Italian connections.” Said Mel, “The transitions…all started between ’35 up until ’40 something, then the Italians got ahold to it.”24

At the international smuggling level, Italian traffickers had established drug contacts throughout the Mediterranean by the 1930s. During this time, the State Department collected “Name Files of Suspected Narcotics Traffickers” on smugglers from around the world. Approximately 11 percent of the name files (65 of the 563 files) were of Italian Americans or Italian nationals.25 They include known Mafia traffickers such as Vincenzo Di Stefano, who in 1935 was convicted for smuggling nineteen kilos of gum opium he bought in Paris aboard the steamship Conte Grande. Mariano Marsalisi, a fifty-something Sicily-born mafioso and businessman, spent much of the 1930s traveling between his residences in Istanbul, Paris, and East Harlem. Marsalisi bought trunks of narcotics all over the Mediterranean for shipment back to New York. In the mid-1930s, his partners Luigi Alabiso and Frank Caruso were convicted on smuggling charges; Marsalisi himself was convicted in 1942.26

The newly formed Federal Bureau of Narcotics (hereafter “FBN”) began tracking the Mafia as it grew in influence in the 1930s. FBN agent Max Roder and George White conducted surveillance in Italian East Harlem and Little Italy along Mulberry Street, tracking mafiosi like Eugene Tramaglino and Joe Marone.27 White and Elmer Gentry later oversaw nationwide investigations of Lucchese Family traffickers.28 The FBN's binder of “major violators of the narcotics laws now operating in New York City” reflects this trend as well. In its February 15, 1940, binder, out of a total of 193 major violators, 84 were Italian (44 percent), and 83 (43 percent) were Jewish.29 Along with labor racketeering, drug trafficking was the Mafia's second new source of revenues in the 1930s.

Prominent mafiosi began getting picked up on narcotics violations in the 1930s as well. Steve Armone, a Gambino Family captain who engaged in “large scale narcotics smuggling and wholesale distribution for many years,” was convicted on narcotics charges in 1937.30 John Ormento, the Lucchese Family's top narcotics man, was first convicted in 1937. Lucky Luciano never stopped consorting with narcotics traffickers: two of Luciano's codefendants in his 1936 prostitution-ring trial were Thomas “The Bull” Pennochio, a notorious drug trafficker on Mott Street whose wife also pled guilty to selling heroin in 1938, and Ralph Liquori, who was convicted on narcotics charges in 1938. Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo, the future boss of the Lucchese Family, got his name for “ducking” convictions on thirteen arrests. Nevertheless, “Tony Ducks” was finally convicted on a state narcotics charge in 1941.31 Drug records did not impede their ascents in the Cosa Nostra.

Joey Rao was innovating another kind of drug smuggling at Welfare Island Penitentiary. The thirty-two-year-old head of the “Italian mob” ran the prison from his luxurious cell, where he donned silk clothes, ate lobster, and smoked cigars. He could stop fights just by walking into the ward. Rao's power derived from his fierce reputation and his “dope racket.” When the Department of Corrections raided Welfare Island in January 1934, it discovered that Rao was running “a systematic traffic in narcotics within the walls.” There were so many addicted inmates that they had to be segregated in the prison hospital.32

5–1: Steve Armone, 1942. Armone, a caporegime in the Mangano/Anastasia Family, was a convicted narcotics trafficker. (Used by permission of the NYC Municipal Archives)

Nicolo Gentile epitomizes the Mafia's hypocrisy on drugs. Born in Sicily in 1885, he entered the “honorable society” as a young man. Gentile became a fixer for Mafia leaders, developing contacts from Kansas City to Pittsburgh to New York. In his memoirs Vita di Capomafia (“Life of a Mafia Boss”), Gentile waxes eloquent about how the Mafia “claims for itself the right to defend honor, the weak, and to command respect for human justice through its affiliated members.”33

So, naturally, Gentile became a drug trafficker. In 1937, Gentile conspired with Charles “Big Nose” La Gaipa to organize one of the largest narcotics distribution rings in America. Gentile used his connections to “organize all the drug trafficking groups and to assemble them in a syndicate, in order to have the distribution monopoly in our hands.” The ring involved more than seventy smugglers and dealers who imported narcotics from Europe to New York City, and then distributed them in Southern states. Financing, underworld reputations, connections to European suppliers—these were advantages enjoyed by the Cosa Nostra. The ring was doing a multimillion dollar business when it was busted. After Gentile was indicted, he skipped bail and slipped onto a ship to Italy.34

THE DISRUPTION OF WAR, 1939–1945

The Second World War cut off the United States from opium sources in Southwest Asia and Southeast Asia, causing severe shortages of narcotics in New York City. Purity levels plunged. “I couldn't deal during the war. I lost my connections. Everybody did,” recalled Jack.35

The Cosa Nostra adapted by looking south for new sources. Although Mexican poppies produced weaker opiates, they would do in a shortage. Mafiosi from East Harlem contacted Helmuth Hartman, a trafficker with connections to Central America. In June 1940, Frank Livorsi, Dominick “The Gap” Petrilli, and Salvatore “Tom Mix” Santoro drove to a remote Texas town to sit down with Hartman: “The boys now have enough money to buy all the narcotics you can find in Mexico. Do a good job for us,” Livorsi told Hartman. They then drove to other towns along the border, striking deals with Mexican traffickers. To oversee the deals, Santoro and Petrilli regularly made road trips to Mexico in their Buick Coupe, and later even flew into Mexico City on Eastern Air Lines.36

Eventually, they and other mafiosi from East Harlem established a reliable drug route whereby curriers smuggled Mexican opium gum into the country through Arizona and California, then across the country to New York City, where chemists in clandestine laboratories processed the opium into heroin. The rings sold the heroin at the wholesale level to dealers for up to $600 an ounce.37

THE POSTWAR RESURGENCE IN DRUGS, 1946–1957

When the sea lanes reopened, narcotics washed over the city. Between 1946 and 1950, New York's addiction rates spiked by 36 percent. By 1957, the US Attorney was calling New York “the illicit narcotics capital of the nation.”38 The Mafia was supplying the heroin.

The Cosa Nostra's traffickers were now the dominant wholesalers due to their superior heroin. “After 1950, I switched over to the Italians in East Harlem because I got better quality stuff, and the prices were better,” recalled Arthur, a dealer.39 The mob's supply was indeed better: the heroin seized in the French Connection case was about 95 percent pure—an extraordinary level. A FBN report in 1949 found that heroin seized at its source in New York City was about 92 percent pure compared to the national average of 55 percent.40

Another sign of the Mafia's market power was its ability to dilute or “cut” its pure heroin while simultaneously raising prices. “When the Jews gave up, I don't know what happened. When the wops come…they kept raising the price,” said Abe D., a Jewish dealer. “It was a beautiful thing when the Chinese and the Jews had it. But when the Italians had it—bah!—they messed it all up,” said Mel. “They started diluting it to a weaker state.” A longtime user concurred: “The Italians stepped on the H much more than the Jews, and they charged more money. It happened before the war,” recounted Al.41

The Mafia's superior supply was due to its overseas connections in the underworld. Members of the Cosa Nostra enjoyed close ties to the premier smugglers of the time: the Corsican crime families. Corsica is a large island situated between France and Italy with a long tradition of banditry. From their base in the port city of Marseilles, the Corsicans had extensive connections with smugglers throughout the Mediterranean. Though French citizens, Corsicans spoke an Italian dialect and were culturally similar to Sicilians.42 The Sicilian cosca and the Corsican crime families were cousins in crime, and they had built up decades of mutual trust. In 1934, the FBN found “a well-organized ring of narcotic traffickers and smugglers in Marseille, most of whom are of Corsican origin,” shipping large quantities of narcotics to Italian smugglers in New York.43

When the war ended, mafiosi revived their prewar contacts with the Corsicans. Upwards of 80 percent of the heroin smuggled into the United States originated in the rich opium fields and port cities of Turkey and Lebanon, where the Corsican smugglers held sway. “The Italian domination really set in with the old French connection, when the predominance of heroin came from Turkey, Lebanon through Italy to Marseilles, following World War II,” explained Ralph Salerno of the New York Police Department's intelligence unit. “Who had the bona fides to sit down with these six Corsican families? Only the Italians, and a few Jews who lingered in the field,” said Salerno.44

Black gangsters by comparison could not establish direct connections to suppliers. The State Department files on international traffickers record no Africans or African Americans.45 “I don't believe there was a black man who could bring into the United States from the outside two kilos of heroin up to 1960,” said Salerno. “You could have had forty million dollars, and if you were a black man, you couldn't even get to sit down with that Corsican.”46 It was not until the 1970s that Frank Lucas, frustrated by the Mafia's dominance, became the first black trafficker to establish a connection to heroin suppliers in Southeast Asia.47

Mafia traffickers further benefitted from belonging to the strongest organized crime syndicates in the underworld. Large-scale, international drug trafficking was a logistical nightmare. A customs officer explained the essential role of organized crime:

You need someone in Europe, you need couriers, you need financing people, you need somebody that knows something about traveling, how to get United States documentation, who the buyers would be in the United States. Only this can be known by someone, and not by some clown who decides all of a sudden to do it in some European capital…. It requires a lot of people, a lot of effort, and it is criminal, so it is organized.48

As FBN agent Maurice Helbrant explained, “Touch dope and you will run into other branches of organized crime. Touch organized crime and sooner or later you will run into dope.”49

THE 107TH STREET MOB

Mafiosi sheltered their wholesaling and distribution operations in Italian East Harlem. These densely populated streets were impenetrable to outsiders. “Since everyone knew everyone else, a narcotics agent found it impossible to maintain surveillance in this neighborhood,” said FBN agent Charles Siragusa. “Life on the narrow sidestreets would come to a standstill. Every eye would fix on the agent.”50

Law enforcement dubbed the Lucchese Family's traffickers the “107th Street Mob.”51 Mafiosi financed, manufactured, and moved heroin through Italian East Harlem. It became an industry cluster for narcotics similar to alcohol wholesaling on the Curb Exchange during Prohibition. Although various Mafia drug traffickers operated in East Harlem, the Luccheses clearly lead the postwar resurgence in drugs. In spring 1947, Charles “Little Bullets” Albero and Joseph “Pip the Blind” Gagliano were convicted of running “an East Harlem narcotics peddling combine said to be the biggest in the East.”52 They were quickly replaced by other Lucchese traffickers.

5–2: John “Big John” Ormento (center) and Nicholas “Big Nose” Tolentino (in glasses) being booked in 1958. The New York Mafia's drug traffickers dominated heroin wholesaling in the United States starting in the mid-1930s. (Used by permission of the Associated Press)

On the surface, John Ormento looked like any other American success story. Born in East Harlem, he rose from his humble origins to live in the fashionable section of Lido Beach on Long Island. By night, Mr. Ormento frequented the Copacabana, his 240-pound frame draped in finely tailored suits. But by day, “Big John” Ormento ran narcotics operations from East 107th Street with his smuggling partner Salvatore “Tom Mix” Santoro. The FBN accurately identified Ormento as a “top figure in the NYC underworld” who knew many “narcotic sources in Mexico, Canada and Europe.”53 By the age of forty, he had three separate convictions under the Harrison Act. Nevertheless, Ormento was a longtime caporegime in the Lucchese Family, and he attended the 1957 Apalachin conference of top mobsters.54

THE DRUG DISTRIBUTION NETWORK

The Cosa Nostra's influence was magnified by New York's pivotal spot in the wholesaling network. As drug historian Eric Schneider explains, “New York served as the central place that established the hierarchical structures of the market, with virtually the entire country as its hinterland and other cities serving as its regional or local distribution centers.”55

Mafia traffickers in New York City financed, diluted, and wholesaled drugs nationwide. Dealers from Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, DC, traveled to New York to buy drugs. In 1924, federal agents discovered that Cincinnati peddlers were getting their narcotics from New York wholesalers. New York mafiosi became the primary suppliers for Chicago, which in turn supplied smaller Midwestern cities. In one major case, traffickers smuggled heroin into New York, cut the heroin in clandestine laboratories, and then redistributed kilo packages to Chicago, Cleveland, Las Vegas, and Los Angeles.56

For the vast market of addicts in New York City, Mafia wholesalers relied on local gangsters for retail street distribution. “The black people handled the largest quantity of drugs after it left the big connections, when it came to the country,” explained Curtis, a black dealer with Sicilian suppliers.57 “The Italians were the ones who brought the dope in, but they didn't have the connects to peddle it,” remembered Bumpy Johnson's widow.58 “The lowest level the Italians would get to was when they sold a quarter kilo to a black—he's the only guy that can successfully sell it in Harlem,” agrees Salerno.59 This move away from retail street distribution and toward wholesaling insulated the Mafia. “The key figures in the Italian heroin establishment never touched heroin,” confirmed David Durk, a narcotics officer.60

The Cosa Nostra established links to major African-American gangsters like Nat Pettigrew and Freddie Parsons to distribute heroin to dealers in black neighborhoods. The FBN discovered that George Anderson “was one of the chief links between the negro dealers in Harlem and the Italian wholesalers in the upper east side of New York City.” Herbert Drumgold bought narcotics “in large quantities from Italian dealers in the Upper East Side of New York City” to resell “to dealers, who in turn sell direct to addicts.”61

Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson oversaw much of the retail heroin distribution in Harlem. “Anyone living in Harlem knew the name Bumpy Johnson. He was a boss,” recalled Frank Lucas.62 Johnson cultivated a façade as a businessman, churchgoer, and benefactor. Behind the scenes, he collected kickbacks from dealers and financed drug operations. Convicted three times on narcotics charges, he helped inundate Harlem with drugs supplied by the Cosa Nostra.63

Once drugs reached the streets, the Mafia had no real control over who bought them. The postwar heroin spike devastated poor teenagers in black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods. “Every time I went uptown, somebody else was hooked, somebody else was strung out,” remembered Claude Browne. “Drugs were killing just about everybody off in one way or another.”64 Low said the addicts were increasingly “Spanish boys in the eighteen, nineteen bracket. I used to see them turning into bums, being all dirty.”65 Piri Thomas grew up on 104th Street (blocks from the mob's trafficking center), and he mainlined heroin as a teenager. “It becomes your whole life once you allow it to sink its white teeth in your blood stream,” Thomas said.66

The Mafia cultivated an image for shielding Italian neighborhoods from drug pushing. “During the 1950s on Mulberry Street, in the lower part of Manhattan, the Italian gangsters’ image was ‘We keep the drug pushers out of the neighborhood.’ And they did,” said Salerno. “But it wouldn't stop them from selling a kilo of heroin to someone, as long as they knew he wasn't going to try to trickle it back into their neighborhood.”67

The notion that the Mafia could build moats around Italian neighborhoods proved illusory. Salvatore Mondello, who grew up in East Harlem during the 1930s and ’40s, recalls:

Some of my friends tried reefers. The racketeers never distributed reefers on the street. It would have been dangerous to sell that stuff on their home turf. Their honest neighbors would have strongly disapproved. But reefers, I imagine, could be bought elsewhere. Some of my friends could have bought them on other streets in East Harlem.68

Though less prevalent, some inner-city Italian youths got hooked on heroin from East Harlem. Dom Abruzzi started snorting heroin “because it was so cheap—a dollar and a half apiece to split a three-dollar bag—and everybody was getting so high and seemed so happy.”69 Eddie became addicted from breathing in the dust from a Mafia cutting operation where he worked. East Harlem was slowly undermined by drugs smuggled into the country by the Mafia.70

IN SEARCH OF A GRAND CONSPIRACY

Politicians and writers have searched for a single, grand conspiracy to explain the entire drug trade. In the 1950s, FBN Commissioner Harry Anslinger and his deputy Charles Siragusa claimed that Luciano was secretly the “the kingpin” of all the narcotics traffic between “the United States and Italy.”71 However, when the drug historians Kathryn Meyer and Terry Parssinen reviewed the FBN's massive surveillance records on Luciano in Italy, they found no evidence that the aging Luciano controlled the transatlantic trade. In my examination of Anslinger's personal papers, I found no prized document showing Luciano pulling the strings of the drug trade from Italy.72

Others have seized on a meeting at the Hotel et des Palmes in Palermo, Sicily, in October 1957. The FBI had long known about this meeting of a dozen Sicilian and America mafiosi, including Joe Bonanno and Carmine Galante. FBI director Louis Freeh later speculated that the meeting was held to enlist the Sicilian Mafia in the drug trade.73 In her 1990 book Octopus: How the Long Reach of the Sicilian Mafia Controls the Global Narcotics Trade, the journalist Claire Sterling saw in this meeting the organization of the entire drug trade:

Although there is no firsthand evidence of what went on at the four-day summit itself, what followed over the next thirty years has made the substance clear. Authorities on both sides of the Atlantic are persuaded by now that the American delegation asked the Sicilians to take over the import and distribution of heroin in the United States, and the Sicilians agreed.74

This has been recycled endlessly, most recently by the writer Gil Reavill who cites Sterling's story even while admitting it is a “largely unsourced account.”75

But there was firsthand evidence of what went on at the 1957 gathering. Tomasso Buscetta was one of the dozen mafioso at the Hotel et des Palmes. Buscetta later became a pentito (penitent witness) after his sons were killed, and he was the key witness in the “Pizza Connection” heroin prosecution of the 1980s. Buscetta never testified that the 1957 gathering was a “summit” to plan a direct Sicily-to-America heroin connection. No such connection was established for another two decades. Wiseguys do not have twenty-year drug plans.76

These writers miss the point. No single cabal could predetermine the entire drug trade. There was conspiracy in the drug trade. But it was not a single grand conspiracy by a few, omnipotent men. Rather, the drug trade involved many small conspiracies, composed of fluid coalitions of mafiosi who put together schemes as the opportunities arose.

MAFIA DRUG OPERATIONS

Joseph Orsini treated countries like his mistresses. A native Corsican, he was convicted of collaborating with the Nazis, and fled France for the United States. In January 1949, he met Salvatore “Sally Shields” Shillitani, a member of the Lucchese Family, and proposed they go into business together. Orsini brought in his Corsican drug contacts; Shillitani brought in his fellow mafiosi. All the partners invested money in a fund to finance their operations. The ring met in restaurants, hotel rooms, a construction company office—even on Ellis Island, as Orsini awaited deportation to Argentina for immigration violations.77

To get heroin to New York, the ring constantly adapted. One of the Corsicans had a connection for opium in Yugoslavia. He shipped the opium to Marseilles, where it was converted into morphine then shipped to Paris to be processed into heroin. The ring then sent Americans with automobiles on “vacations” to Paris, where the cars were loaded up with heroin in hidden caches and shipped back to the United States. The ring was hardly flawless. Investors squabbled over deliveries. The automobile scheme was shut down when too many cars were returning empty. One disastrous day, French police seized a three-hundred-kilo shipment from a boat docked in Marseilles. But because the ring's “merchandise” was so perfect, it still made profits from the kilos that made it to New York.78

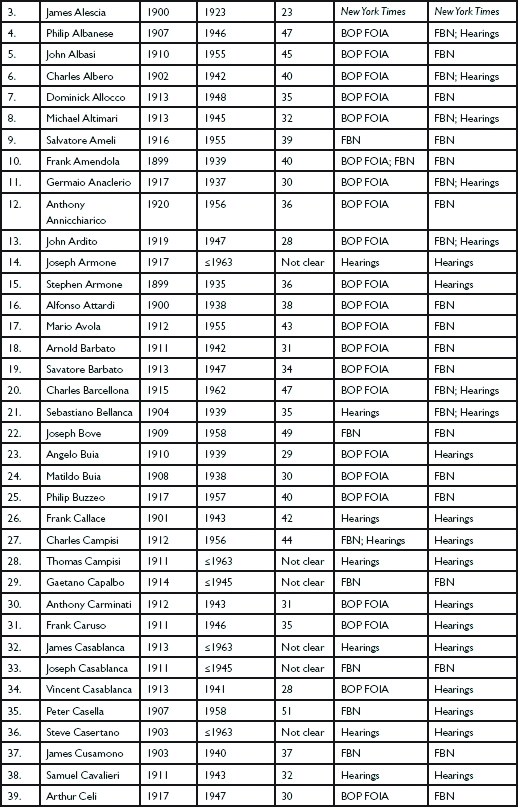

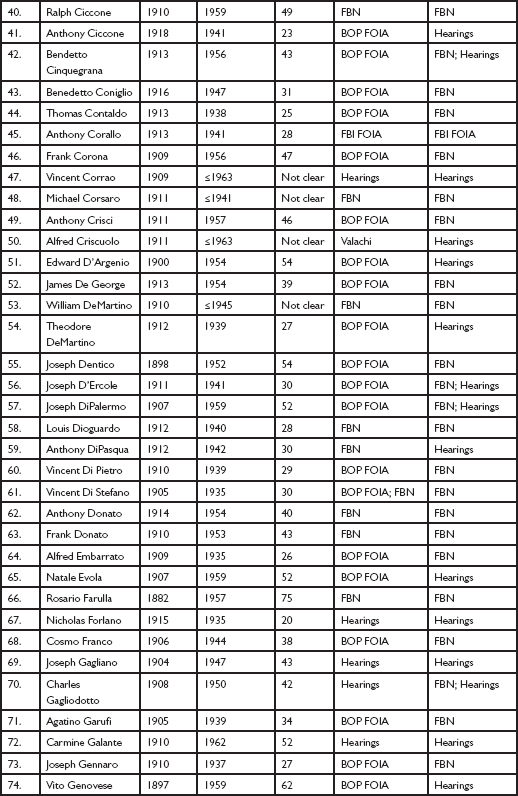

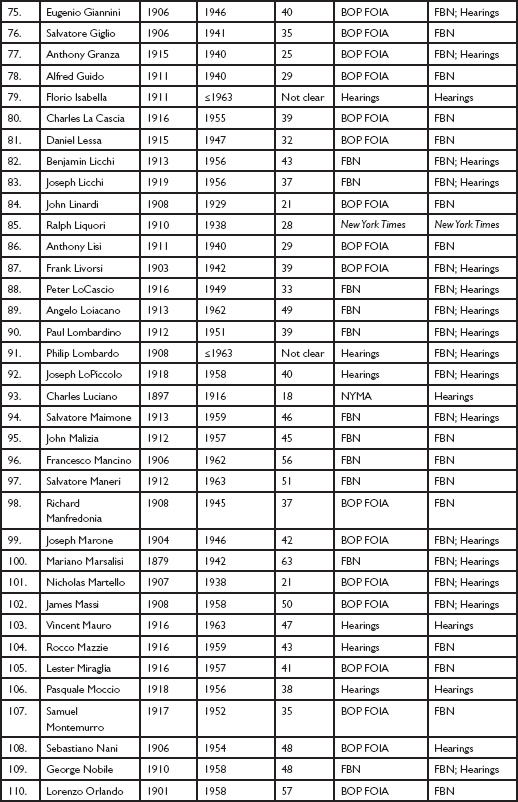

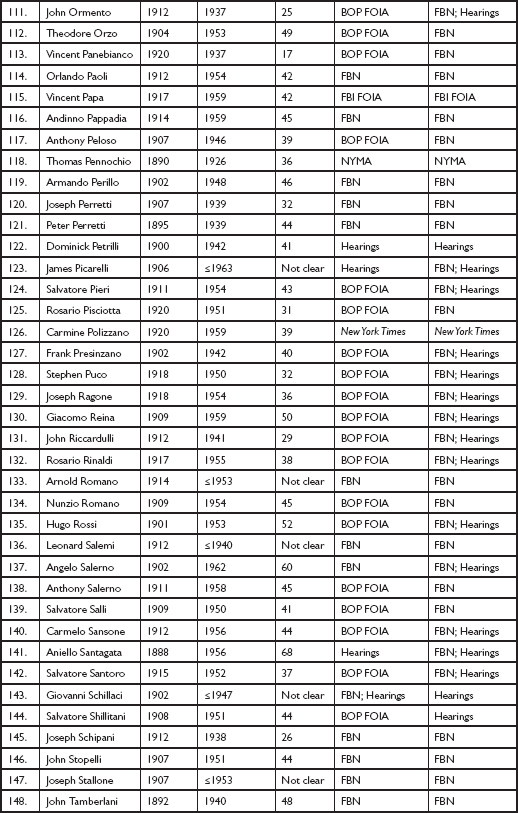

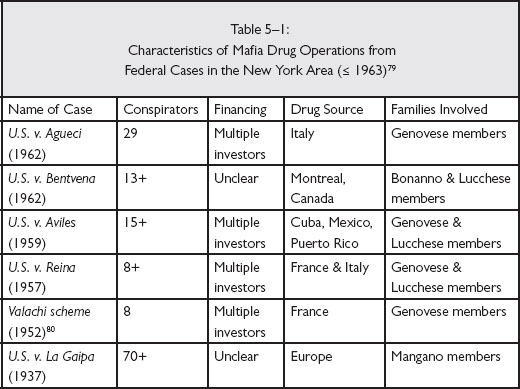

The Orsini-Shillitani ring was fairly typical of Mafia drug rings. Table 5–1 summarizes characteristics of Mafia drug operations for which we have good information. First, the drug rings involved many different coconspirators. Second, they were financed by several mafiosi pooling their money. Third, the drug rings were opportunistic. Traffickers crossed Mafia family lines, bought from whatever source was available, and smuggled in the drugs by any means necessary.

THE FRENCH (CANADIAN) CONNECTION

When viewed against this background, the famous “French Connection” case of the early 1960s looks less the mark of something new and more like any other Mafia drug operation. The case was immortalized by William Friedkin's 1971 Academy Award–winning film The French Connection starring Gene Hackman. The reporter who wrote the book on which the film was based trumpeted the case as “The World's Most Crucial Narcotics Investigation.”81 It wasn't.

In reality, the scheme was a small, family affair involving Pasquale “Patsy” Fuca, his brother Joe, and his father Tony. Patsy's uncle was Angelo “Little Angie” Tuminaro, a trafficker for the Lucchese Family. With their Corsican partners, they refined Turkish opium into heroin in Marseilles. They concealed the heroin in the undercarriage of a 1960 Buick Invicta owned by a Parisian television host, who shipped his car to Montreal, Canada. After smuggling the packages across the border, they stashed the ninety-seven pounds of heroin in cellars around New York.82

The case might have been called the French-Canadian Connection to reflect the Mafia's latest adaptation to the drug war. The Canadian Mafia long had its own drug trade. Canadian boss Rocco Perri's associates were into narcotics trafficking as early as the 1920s.83 When customs enforcement increased on the New York waterfront in the late 1950s and the 1960s, the wiseguys looked north for new drug routes. “When the heat was being put on New York [traffickers would] swing through French Canada because of all the [Montreal] air traffic,” explained Ralph Salerno.84 This gave rise to mob traffickers like Frank and Joseph Controni of Montreal, and Albert and Vito Agueci of Toronto, who smuggled drugs through Canada to New York City.85

NARCOTICS CONVICTIONS OF MAFIOSI, 1916–1963

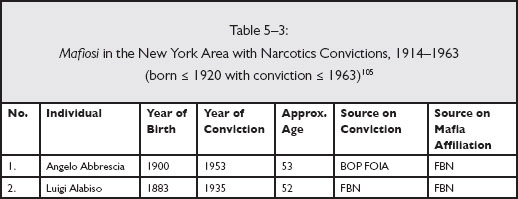

The Mafia's entrenchment in the narcotics trade is also reflected in conviction rates. Table 5–3 below shows mafiosi from the New York metropolitan area convicted on drug charges. To address the myth of generational decline, the table is limited to mafiosi who were both born by 1920 and convicted by 1963. This places them in the same generation as the leading purveyors of this myth, Joe Bonanno (born 1905) and Angelo Lonardo (born 1911). The pre-1963 time limitation counters the perception that Mafia trafficking only began with the French Connection case, or as Lonardo put it “the late sixties or seventies.”

As the table shows, more than 150 mafiosi in the New York area alone were convicted on narcotics violations by 1963. Given that Joe Valachi testified there were about two thousand active and twenty-five hundred inactive members in the New York area, this meant that one in thirty-three mafiosi were convicted traffickers. This is astounding given how weak narcotics enforcement was at the time. As late as 1950, the NYPD's narcotics squad had 18 officers; in 1965, the FBN had only 433 employees nationwide. Many mob traffickers evaded the law. Valachi estimated that about “75 tops, maybe 100” in the 450-man Genovese Family were into narcotics—about one in six.86

MAFIA LEADERS INVOLVED IN DRUGS

Contrary to myth, drug trafficking was not confined to low-level mobsters. Table 5–2 below shows that all five families had high-ranking leaders with early narcotics convictions:

| Table 5–2: Known Leaders of the New York Families with Narcotics Convictions (≤ 1963) | ||

| Individual (earliest narcotics conviction) | Top Position Obtained | Family |

| Charles “Lucky” Luciano (1916) | Boss | Genovese |

| Dominick “Quiet Dom” Cirillo (1953) | Boss | Genovese |

| Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno (1958) | Boss | Genovese |

| Vito Genovese (1959) | Boss | Genovese |

| Vincent “The Chin” Gigante (1959) | Boss | Genovese |

| Natale “Diamond Joe” Evola (1959) | Boss | Bonanno |

| Carmine “Lilo” Galante (1962) | Boss | Bonanno |

| Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo (1941) | Boss | Lucchese |

| Salvatore “Tom Mix” Santoro (1952) | Underboss | Lucchese |

| Stephen Armone (1935) | Caporegime | Gambino |

| Joseph “Joe Piney” Armone (≤1963) | Caporegime | Gambino |

| Joseph “Jo Jo” Manfredi (1952) | Caporegime | Gambino |

| Rocco Mazzie (1959) | Caporegime | Gambino |

| John “Big John” Ormento (1937) | Caporegime | Lucchese |

| Nicholas “Jiggs” Forlano (1935) | Caporegime | Magliocco |

The bosses profited from narcotics behind the scenes, too. Nicolo Gentile's boss Vincent Mangano approved of Gentile's drug trafficking scheme in exchange for a split of the profits.87 Joe Valachi recalls a highly revealing conversation he once had with his boss, Vito Genovese:

He said to me, “Did you ever deal in junk?”

I said, “Yes.”

He said, “You know you ain't supposed to fool with it.”

Vito looked at me and said, “Well, don't do it again.”

“Okay,” I said.

Of course, I don't pay any attention to this. This is how Vito was.88

This veiled conversation shows how easily a mob boss could look the other way.

Joe Bonanno's pontifications on drugs are undermined by some damning facts as well. Bonanno portrays his “hero” Salvatore Maranzano as the quintessential “Man of Honor.” Yet as we saw earlier, Maranzano had a convicted drug trafficker in James Alescia as a partner at his Park Avenue office. Bonanno offers no explanation for Maranzano and Alescia.89

“I did not tolerate any dealings in prostitution or narcotics,” Bonanno claimed when he was boss. But in 1959, Carmine “Lilo” Galante, a caporegime in the Bonanno Family, was arrested and later convicted for smuggling heroin through the Montreal airport and into New York City.90 Not only was Galante left untouched, but he later became acting boss of the Bonanno Family.91 Joe Bonanno conveniently omits any mention of Galante in his autobiography Man of Honor. Bill Bonanno tries to shore up his father's omission in Bill's own 1991 autobiography Bound by Honor. Bill admits that Galante was a trafficker, but claims his father had no forewarning:

My father was heartbroken by this, although unwilling to do anything about it. There was a standing death sentence for anyone who openly defied an ironclad rule of the Family—such as the one against dealing drugs.

“Leave him alone; doesn't matter now,” my father told me and those in the administration of the Family.

Bill Bonanno claims that he “would have struck out in retaliation” against Galante. However, in a 1979 New York Times article, Bill Bonanno is quoted as saying that Carmine Galante “was like an uncle,” and that Bill was a “godfather to one of [Galante's] children.”92

Then there is Natale “Joe Diamond” Evola. Natale Evola was an usher at Joe Bonanno's wedding, and the Bonannos lionize Evola as one of the “boys of the first day.” In 1959, however, Evola was convicted for a narcotics conspiracy. Nevertheless, Evola became boss of the Bonanno Family in the 1970s, and the Bonannos say nothing of his drug record.93 The facts, it seems, would have gotten in the way of a good myth.

POLICE CORRUPTION

Don Corleone was wrong about the police refusing to help, too. The FBN, in fact, was borne out of a corruption scandal in its predecessor agency, the old Narcotics Bureau. In 1930, a grand jury in New York charged narcotics agents with rampant misconduct and falsification of cases under its commissioner Levi Nutt. But what brought Nutt down were the revelations that his son-in-law took a loan from Arnold Rothstein, the biggest narcotics trafficker in the country, and that Nutt's own son represented Rothstein in a tax-evasion proceeding.94

The FBN's New York office became a den of corruption. When rookie agent Jack Kelly joined the New York office in the early 1950s, he was warned to “try to find someone honest or at least honest when they are working with you.” FBN agent Tom Tripodi saw agents routinely take money in raids; they called it “‘making a bobo’ (a bonus).” Corrupt agents rationalized this by saying they were just taking “Mob money. Drug money.”95

The FBN was a paragon of virtue compared to the narcotics units of the NYPD. “I won't say that every New York City police officer was dishonest, but finding one who wasn't was an exception,” said Kelly.96 In 1951, a Brooklyn grand jury found that “from top to bottom of the plainclothes division,” the police had formed “criminal combines” with narcotics peddlers. The Knapp Commission later singled out corruption in the narcotics units as the most serious problem facing the NYPD.97

Corruption insulated traffickers on multiple levels. “The New York Police Department charged me two thousand dollars a month in order to operate between 110th Street and 125th Street,” said Arthur. “I couldn't get busted in there. I was on the pad.” The Cosa Nostra neutralized high-level investigations, too. If narcotics agents uncovered a mafioso during an investigation, the target would disappear, and the agents would be sent off on a wild goose chase by a senior officer on the take. When Frank Serpico joined the plainclothes division, he was told he could arrest blacks and Puerto Rican dealers, but “the Italians, of course, are different. They're on top, they run the show, and they're very reliable, and they can do whatever they want.” In 1969, nearly the entire seventy-six member elite Special Investigation Unit (SIU) of the NYPD was transferred out on corruption charges.98

The low point was the mob's theft of the heroin seized in the French Connection case. The NYPD had stored the ninety-seven pounds of heroin they had seized in the case in the NYPD's Property Clerk's Office. Then eighty-one pounds of it, with a street value of $10 million, disappeared. The mastermind was Vincent “Vinnie Papa” Papa of the Lucchese Family. After the debacle, NYPD commissioner Patrick Murphy concluded that “the single most dangerous feature of organized crime syndicates was their ability to corrupt or co-opt local law enforcement.”99

MAFIA EDICTS AGAINST DRUGS

There is one grain of truth in the mythology. Some Mafia leaders did issue bans on drugs. According to Joe Valachi, in 1948, Frank Costello, boss of the Luciano Family “ordered its membership to stay out of dope.” The next edict was issued in 1957 when “all families were notified—no narcotics.” This ban was largely ignored, too.100 Wiretaps of the DeCavalcante Family in New Jersey record their amazement at all the drug dealing: “Half these guys are handling junk. Now there's a [Mafia] law out that they can't touch it.”101

Still others tried issuing “no-drugs” orders in their families. Mob boss Paul Castellano barred narcotics under penalty of death, yet Castellano's own consigliere had a son who dealt. Lucchese Family caporegime Paul Vario outlawed dealing in his crew after his boss Carmine Tramunti was convicted on drug charges. It did not matter. Vario could not stop his own crew from dealing.102 The ineffectiveness of these bans shows that “the godfathers” were not omnipotent.

There were human factors at work, too. Hypocrisy was part of the mobster life. Vito Genovese's veiled conversation with Joe Valachi shows how the bosses looked the other way. Bill Bonanno likewise suggests willful ignorance. He admits that “the Family's Administration…received envelopes of cash from time to time in exchange for keeping quiet. No one asked questions about where this money came from or how it was earned.”103

Some mafiosi were in denial, too. In the 1930s, public opinion turned strongly against drug sellers as middle-class users devolved into street addicts. No one was lower than the “dope fiend” except the “junk dealer.” Even hardened mafiosi had trouble admitting they were into narcotics. Although Joe Valachi readily recounted murders he committed, he sheepishly downplayed his drug dealing, claiming he only sold “small amounts to get back on my feet.” In fact, the FBN had been tracking Valachi's drug trafficking since the 1940s, and it obtained multiple convictions of him. Meanwhile, Nicolo Gentile tried to blame his involvement with narcotics trafficking on woman problems and business debts.104

It seems even wiseguys could feel shame. Just not enough to stop taking their cut.