Anything can happen now that we've slid over this bridge…anything at all.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1925)

Don't ask me why, but people seem to want to come to a mob place. Maybe it's the excitement of mingling with mobsters.

—Vincent “Fat Vinnie” Teresa, My Life in the Mafia (1973)

Thirty-year-old Frank Sinatra walked off stage after 2:00 a.m. to the whistles of adoring patrons under the papier-mâché palm trees of the Copacabana in midtown Manhattan. Sinatra had flown in from Hollywood, where he'd been filming It Happened in Brooklyn, to make a surprise appearance beside comedian Phil Silvers (who later played Sergeant Bilko on The Phil Silvers Show). In the audience were Broadway singer Ethel Merman, Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright Sidney Kingsley, actress Paula Stone, and restaurateur Toots Shor. Gliding among them were the “Copa Girls,” the nineteen-year-old ingénues whose long legs and demure smiles became club trademarks under the talented management of Monte Prosser.1

Presiding over the Copa behind the scenes was its hidden owner, Frank Costello. Mr. Costello was the bootlegger turned businessman, the street gangster who became a political fixer—and the secret acting boss of the Mafia's Luciano Family. Or as his nickname said, he was the “Prime Minister of the Underworld.”2

Nighthawks who stepped out on the town for jazz on 54th Street, or drinks at a nightclub in the Village, or a prizefight at Madison Square Garden were at some point enjoying a mob-run production. Gangsters had an outsized influence over Manhattan's nightlife. They kept the doors open and the booze flowing. Mobsters, or glamorized versions of them, became part of the nightly allure. This chapter is a tour through the mob nightlife.

THE LINGERING HANGOVER OF PROHIBITION

The Mafia's influence over Manhattan's nightlife was due to the lingering aftereffects of Prohibition. The mix was one part cultural and one part legal.

Repeal ended the ban on alcohol, but not gangsters in the liquor business. Between 1920 and 1933, speakeasies were the only place where drink and music could be enjoyed together. The Jewish and Italian gangsters who ran them loved the nightly entertainment business. So when Prohibition ended, many former bootleggers and speakeasy operators slid over to newly legal bars and nightclubs.3 “Nightclubs are big business for mob guys. They pick them because they like to cabaret, themselves,” recalled Vincent “Fat Vinnie” Teresa. “It's also a place to go where you'll find women, loads of women, and you get a chance to be in the limelight.”4

Although section one of the Twenty-First Amendment famously provided that Prohibition “is hereby repealed,” lawmakers wary of returning to the wide-open saloon also inserted section two, which gave the states virtually unlimited power to regulate booze.5 In 1934, New York's State Liquor Authority (NYSLA), began issuing a dizzying array of regulations over bars and nightclubs. The NYSLA could revoke a liquor license—a death sentence for nightspots—for anything from “improperly marked taps” to “undesirables permitted to congregate.”6 What's more, such violations could be reported by any beat cop on the street.

This bred venality in the nightclub business. As the Knapp Commission on police corruption found: “Selling liquor by the drink is governed by a complex system of state and local laws, infractions of which can lead to criminal penalties, as well as suspension or loss of license.” As a result, liquor “licensees are highly vulnerable to police shakedowns.”7 Mobsters were often the ones keeping the cops at bay.

JAZZ CLUBS ON 52ND STREET

For New Yorkers wanting to hear the new music coming out of New Orleans during Prohibition, speakeasies were the place to go. Gangsters became an inseparable part of the jazz scene. At the Cotton Club in Harlem, Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway created the music of the Harlem Renaissance. Its owner was the bootlegger Owney “The Killer” Madden, and its patrons included mafiosi like Joe Valachi. This was not unusual. As a New York jazzman said, “no popular speakeasy seemed devoid of hoodlum associations, backing or control, regardless of whether a top performer's name like Club Durant or Club Richman appeared on it.” In Chicago, Al Capone, a jazz enthusiast, controlled the top clubs. “To our amazement Capone would come over to the bandstand every few minutes or so and give each member of the band a twenty-dollar bill and then return to his table beaming and smoking fat cigars,” recalled Teddy Wilson.8

Many bootleggers and speakeasy operators shifted over to legitimate clubs after Repeal. The bootlegger and jazz enthusiast Joe Helblock opened Onyx on West 52nd Street, a platform for Charlie “Bird” Parker and Dizzy Gillespie as they were inventing modern bebop. Sherman Billingsley, an ex-convict who worked for the Detroit mob, first opened The Stork Club as a speakeasy with underworld partners, including for a time Frank Costello. The Stork Club on East 53rd Street became a fashionable nightspot where celebrities like Lucille Ball and Damon Runyon mixed with wiseguys like Sonny Franzese.9

Although mob clubs offered essential venues, they were tough, treacherous places for musicians. “Around New York and Chicago ‘The Boys’ pretty much told you where you were going to work. The union didn't say nothin’,” said jazz bassist Pops Foster. “The working conditions were horrible, really,” recounted pianist George Shearing. When jazzman Mezz Mezzrow was going through heroin withdrawal, his nightmares were of the mobsters: “Legs Diamond and Babyface Coll and Dutch Schultz and Scarface and Louis the Wop, along with a gang of other mugs I couldn't quite recognize but still their murderous leers were sort of familiar, had been chasing me all over the Milky Way,” dreamed Mezzrow. Louis Armstrong spent his early career dodging mobsters until he hired Joe Glaser (a man who once worked for Capone) to be his manager. Glaser “saved me from the gangsters,” said Satchmo.10

6-1: Times Square, 1933. Even after repeal of Prohibition in 1933, the mob had an outsized influence on Manhattan's nightlife. (Photo by Samuel H. Gottscho, courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Gottscho-Schleisner Collection)

THE COPACABANA, 10 EAST 60TH STREET

The Copacabana at 10 East 60th Street was the center of the mob nightlife in Manhattan. On any night, there was “someone from each family in there,” confirmed a mafioso. Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano and Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno kept a regular table with boxing mobsters Frankie Carbo and Frank Palermo. In they'd strut in silk suits, ridiculing waiters, then making up for it with big tips. When they wanted to talk business, wiseguys paid the wait captain to keep nearby tables unoccupied.11

Mobsters were part of the Copa's electric atmosphere. Hollywood actors, judges, and New York Yankees would literally bump into mafiosi like Joseph “Joe Stretch” Stracci or Frank “Frankie Brown” Bongiorno. They became part of the allure of the Manhattan nightlife. “A well-known gangster was respected as much as any movie star or politician,” said actor George Raft. To most night owls, who never saw the barrel end of their guns, they were no more threatening than underworld characters from The Great Gatsby.12

Frank Sinatra had great times with the boys at the Copa. He had been looking up to them since his childhood in Hoboken, New Jersey, where young Francis grew up a skinny, lonely only child in the same neighborhood as Angelo “Gyp” DeCarlo, a caporegime in the Mafia. On his way up the nightclub circuit, Sinatra became pals with Willie Moretti, a vicious enforcer for Frank Costello.13

Sinatra's mob connections were first exposed in February 1947 when a newspaper revealed that he had given a special performance in Havana, Cuba, for a gathering of Lucky Luciano with other mobsters. Then, in August 1951, bandleader Tommy Dorsey told the American Mercury that when Sinatra was trying to get out of his band contract, Dorsey was intimidated into signing a release of Sinatra after being visited by three toughs who said “sign or else.” Notwithstanding the bad publicity, Sinatra continued to socialize and do business with mafiosi. In 1962, Sinatra invested $50,000 in the Berkshire Downs horse track, which witnesses testified was secretly owned by the Patriarca Family. In 1963, the Nevada Gaming Control Board pulled his gaming license for hosting Sam Giancana at Sinatra's Cal-Neva Lodge.14

6–2: Singer Frank Sinatra talking with boxer Rocky Graziano at the Copa, 1946. (© Bettmann/CORBIS)

While denying his mob connections publicly, behind closed doors the Chairman of the Board was something of a want-to-be mobster who socialized with mafiosi throughout his adult life. “Sinatra's always talking about the mob guys he knows. Who gives a damn, especially if you're a mob guy yourself?” said Vinnie Teresa. He was drawn to the life. “Frank Sinatra loved gangsters, or at least the world they lived in,” observed George Jacobs, his longtime valet. But he was no gangster himself. “Dad was interested in the wise guys because they were so different from him,” explained his daughter. The skinny kid from Hoboken with the tough-guy persona was imitating life.15

PROFESSIONAL BOXING

Professional boxing was always a controversial sport on the edge of the law. Congress actually outlawed the interstate transportation of fight films between 1912 and 1939. The New York legislature did not fully legalize decision prizefights until 1920, believing they promoted gambling. Gamblers hovered around boxing gyms to get tip-offs—or worse, a deal to fix a fight—from boxers. The gambling stakes grew after the advent of nationally televised boxing matches. Mobsters lived in the same rough world as pugilists and were naturally drawn to them, too.16

The New York State Athletic Commission (NYSAC) was the nominal regulator of the sport. It had dismal beginnings. In 1925, promoter Tex Rickard was forced to hand over 25 percent of the gross receipts of the fight between Jack Dempsey and Luis Firpo to William J. McCormack, licensing commissioner of the NYSAC, “for his permission to let the fight go on.”17 Mostly, the NYSAC was just ineffectual. It was difficult to prove a gangster's hidden interest in a fighter. Even when the NYSAC issued a suspension, promoters crossed state lines to find another sanctioning body.18

“The Combination”

The Cosa Nostra moved into prizefighting in the 1930s principally behind Paolo “Frankie” Carbo and his partner Frank “Blinky” Palermo. Carbo was born on the Lower East Side in 1904 to respectable parents who found themselves with an incorrigible child and sent him away to a Catholic protectory. The nuns could not stop young Carbo's thirst for the criminal life: the police would arrest him twenty different times for charges ranging from juvenile delinquency to murder. In 1924, when he was twenty years old, Carbo killed a taxicab driver in the Bronx. He went on the lam for four years before pleading guilty to manslaughter in 1928.19

6–3: Frankie Carbo, ca. 1928. Carbo was a de facto boxing commissioner due to his influence over managers and fighters. (Used by permission of the John Binder Collection)

After getting out of Sing Sing, Carbo was looking for new enterprises, and he was drawn to the fight game. In the early 1930s, he started hanging around the famed Stillman's Gym on 55th Street and 8th Avenue in midtown Manhattan.20 The mafioso was enthusiastic and knowledgeable about boxing, charming everyone from lowly pug fighters to top promoters. “I like boxing. I don't know other business,” he told confidants. Still, Carbo was foremost a solider in the Lucchese Family. His business consisted of taking hidden interests in boxers, bookmaking bets on fights, and then fixing those fights.21

Carbo's partner was Frank “Blinky” Palermo of Philadelphia. They were a feared pair. “Blinky” was a bug-eyed, gravel-voiced, strutting rooster of a man with ties to Philly's Jewish gangsters. Carbo was the shadowy power broker they called “Mr. Gray.” Both loved boxing and making money off boxing. They and their associates came to be known as “The Combination,” the underworld's commissioners of boxing.22

They captured professional boxing using tactics not unlike those the Mafia used elsewhere: they targeted fragile producers (individual boxers), gained control over key geographic spaces (Madison Square Garden), and used coercive industry associations to keep everyone in line (the Boxing Managers Guild and the International Boxing Club).

Fragile Fighters

The boxer, for all his athletic strength, had a glass jaw in the mob system. Most came from working class backgrounds, with little education and few prospects outside the ring. And they could not get into the ring unless they fought by the mob's rules. “You want to know why they control boxing? It's poor, hungry people,” said former welterweight champion Don Jordan of the mob's influence. “In each state there's another syndicate person waiting to see you.”23

Fighters could only get professional matches through mobbed-up managers. When the young Rocco Barbella (the future “Rocky Graziano”) started showing promise, neighborhood gangsters sent him his first professional manager, Eddie Coco. “You better do what Eddie says. He's an important guy and he's going to get you some matches,” they told him. Coco changed Barbella's name, arranged his first pro matches, and told him when to “carry” an overmatched opponent. “No fighter can get anywhere without us,” mob guys warned a young Jake LaMotta. “Carbo had the middleweight division sewed up,” recalled the fighter Marty Pomerantz. “They made sure there was a huge amount of betting. ‘Don't knock this guy out. Knock that guy out. Maybe you don't have to win this.’ All of that went on.”24

Prizefighters who refused to carry a weaker opponent, or take dives, could be shut out from future matches. “The implication is that if you don't do certain things, you're not going to get certain fights,” explained Danny Kapilow, a boxer in the 1940s. “You were almost blackballed at that time.” It is sometimes forgotten that Jake La Motta took his infamous dive against Billy Fox (managed by Palermo) to get a title shot for the middleweight crown.25

Boxers knew even worse things could happen. “With Steve [Belloise], there came a time in the ’40s that he started to talk around the gym about the fighters’ organizing,” recounted Kapilow. “Somebody quickly put a piece in his ear. That was the end of that. They're not going to talk about it.” As former heavyweight champion Joe Louis testified in retirement, “Fighters have been taken advantage of by the underworld. A lot of managers, even a lot of promoters, get backing from outside world, outside people, who are gangsters and hoodlums.” Louis, who ended up broke himself, could have been speaking from personal experience.26

Madison Square Garden, Eighth Avenue and 50th Street

For boxers, the apex was a fight at the old Madison Square Garden, in operation from 1925 through 1968. The cavernous arena in Hell's Kitchen could seat eighteen thousand spectators, all seemingly atop the ring. The Garden was described as “the center, the pivot of boxing” in America.27

Carbo gained access to the Garden through the legendary promoter Michael “Uncle Mike” Jacobs of the Twentieth Century Sporting Club. In the 1930s, Jacobs skillfully promoted a young Joe Louis, the first African-American heavyweight champion to gain a nationwide following. He parlayed the Brown Bomber's popularity into an exclusive lease of the Garden.28

The problem with success was that Jacobs suddenly needed lots of boxers to fill matches at the Garden. Carbo had scores of fighters in his pocket. Soon, the Lucchese Family soldier would be dictating fight cards on the nation's premier boxing stage.29

The Boxing Managers Guild

Carbo and Palermo maintained power through their influence over the managers. When most managers made less than $1,000 a year (less than $8,000 a year in present dollars), Carbo was known for doling out cash to struggling managers for food or rent. Managers became so ingratiated that when they found their newest fighter, “Mr. Gray” came calling for favors. Carbo and Palermo's influence extended to every corner of the fight game. Outside New York and Philadelphia, they had collusive arrangements with managers in the Midwest boxing centers of Chicago, Detroit, Toledo, and Youngstown, Ohio.30

Their power was enhanced by the Boxing Managers Guild. This shadowy front operated on subtle extortion and hidden interests. Out-of-state boxing managers were forced to “cut in” the guild before they could even hope to get a fight in New York. Television contracts for fights were decided behind closed doors by the guild, which favored fighters in which Carbo and Palermo held interests. An investigation later found that the guild “engaged in monopolistic practices” and “abrogated to itself the conduct and regulation of boxing in New York.”31

When economic coercion was insufficient, Carbo and Palermo drew on past talents. After the boxing promoter Ray Arcel staged Saturday fights without Carbo's permission, he was assaulted with a steel pipe in front of Boston Garden. Subsequently, four bombs ripped through the Boston house of Arcel's business associate Sam Silverman. “The threat of the same for anyone else even thinking about not cooperating with Carbo & Co. was enough to bring the entire sport into line,” recalled trainer Angelo Dundee.32

December 1946, Stillman's Gymnasium on Eighth Avenue

The stench of sweat permeated the dressing room at Stillman's Gymnasium, where up-and-coming boxers trained. “How you feel Rocky? Like to make a good deal on this fight?” offered the gambler. The boxer Rocky Graziano was in training for his match against “Cowboy” Reuben Shank at Madison Square Garden on December 27, 1946. The gambler reappeared a few days later. “Don't forget that that deal is still on. You'll make a hundred grand,” he said to Graziano.33

After the District Attorney's office went public with the bribe offer, Graziano tried to backpedal from his original account, claiming he thought the offer was “a joke.” Still, the entire situation reeked. Graziano's manager was Eddie Coco, a caporegime in the Lucchese Family (who in 1953 killed a car wash owner over a bill). The knockout artist Graziano was a 4-to-1 favorite over the journeyman Shank, but a gambling syndicate was reportedly placing huge bets on Shank. Suddenly, on Christmas Eve, two days before the match, Graziano pulled out of the fight claiming a back ailment.34

The District Attorney's office believed Graziano knew gangsters had already bet heavily on Shank, and he was worried about crossing them if he did not take a dive. The New York State Athletic Commission (NYSAC) temporarily revoked Graziano's license for failing to report the bribe offer. The 1946 bribe debacle portended an era of scandal in boxing that ultimately brought down Carbo and Palermo.35

The Downfall of the International Boxing Club

The most audacious monopoly in boxing was initiated not by gangsters, but by prestigious businessmen. Truman K. Gibson Jr. was a prominent Chicago lawyer and civil rights leader who had helped heavyweight champion Joe Louis with his tax problems. In 1949, Gibson approached James Norris and Arthur Wirtz, who controlled the Chicago Stadium, the Detroit Olympia Arena, and the St. Louis Arena, and proposed that they create a dominant boxing promotion company: the International Boxing Club (IBC). They first struck a deal with the aging Joe Louis: in exchange for shares in the IBC, Louis would secure exclusive fight contracts for the IBC with the four leading contenders and then give up his heavyweight title. In the euphemisms of monopoly, it was proposed that they all “work together now and keep the events for our building and not create a competitive situation that would be harmful to all.”36

The only problem was that they had left Carbo out of the scheme. Gibson explains what happened next. “In New York the first fight that we tried to stage, the Graziano-La Motta fight, suddenly was called off because Graziano developed an illness and we had a picket line around Madison Square Garden,” Gibson recounted. They knew instantly who was behind it. “T]he organization of managers…the Carbo friendship with managers over the years,” cited Gibson. Cosa Nostra was threatening the IBC's ability to fill its fight cards. “I was having a great deal of guild trouble,” James Norris concurred. So they decided “to live with” the underworld. They put Carbo's very pretty, if very unqualified, girlfriend Viola Masters on their payroll and funneled “goodwill” payments to him through business fronts.37

As the 1950s went on, and rumors of fixed fights threatened to destroy the sport, government officials were pressured to go after Carbo, Palermo, and their business associates. First, in July 1958, the Manhattan District Attorney's Office brought misdemeanor charges against Carbo for his unlicensed management of fighters. In the middle of trial, he pled guilty.38

To break up the IBC, the Justice Department brought a federal civil action against the IBC for violating the Sherman Antitrust Act. In January 1959, the United States Supreme Court affirmed the trial court's judgment, holding that the IBC was a monopoly. The trial court had found that the IBC had used its power to promote 93 percent of all the championship fights in all divisions.39

Then, in September 1959, the United States Attorney for Los Angeles brought federal criminal charges against Carbo and Palermo, Truman K. Gibson Jr., and mafiosi Louis Dragna and mob associate Joe Sica for using extortion “to obtain a monopoly in professional boxing.” Promoter Jackie Leonard testified that Carbo and Palermo were dictating his fight cards in Los Angeles and trying to muscle in on the earnings of welterweight champion Don Jordan. When Leonard resisted, Joe Sica told him “the same thing could happen to me that happened to Ray Arcel.” Shortly after, Leonard was assaulted outside his garage. The jury convicted the defendants, and the judge sentenced Carbo and Palermo to twenty-five years in prison.40

Their glorious nights at the Copa were done.

OUTLAWING GAY LIFE IN THE 1930s

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the mob nightlife was the Mafia's ownership of gay bars and nightclubs. The Mafia specialized in illegal markets, which is what gay bars became in Gotham. The historian George Chauncey has shown that gay life was remarkably visible from the 1890s until it was forced underground in the 1930s. New York State's liquor laws barred “disorderly” premises, which the NYSLA interpreted as serving drinks to gays and lesbians, and the City of New York barred the employment of homosexuals. The NYSLA and NYPD closed hundreds of gay bars in the 1930s and ’40s. Using this threat, vice police shook down bars “which catered heavily to…homosexuals soliciting partners,” according to the Knapp Commission on police corruption.41

Wiseguys muscled in on the vulnerable owners of gay establishments with protection rackets and skimming operations. “Even if you came in [and] tried to open a gay bar, you would be contacted by the Family, and be informed it was a closed shop,” explained a bartender. Cosa Nostra then had the cash and clout to keep open gay bars in which it held hidden interests.42

Though it seems unthinkable today, there were also cultural reasons for the Mafia's association with gay bars. Chauncey has documented the presence of many finocchio (“fairies”) among working-class, southern Italian men in the early 1900s; Italian bachelors would get serviced by finocchio without thinking themselves gay. During Prohibition, gangsters ran the speakeasies with “coarse” entertainment like Dutch Schultz's Club Abbey on West 54th Street, featuring Jean Malin's “pansy act” show.43

Even in its formative decades, the Cosa Nostra had some members who engaged in forms of same-sex acts or transgender dressing. According to FBI informants, David Petillo “in his early teens was reputed to be a ‘fairy,’” and “dressed as a woman” to disguise himself while executing hits. (Petillo was convicted with Charles Luciano for compulsory prostitution in 1936). Similarly, Charles Gagliodotto reportedly wore dresses and carried his gun in a purse so often he was known in the Genovese Family as the “fag hit-man.” Later, the wiseguy operator of the Stonewall Inn, whose father was a prominent mafioso, had male lovers. Mobster Joseph “Crazy Joey” Gallo talked about how “normal, natural and unremarkable” homosexuality was in prison. Gallo held interests in gay bars including the Purple Onion and Washington Square.44

Gay Nightclubs in the 1930s and ’40s

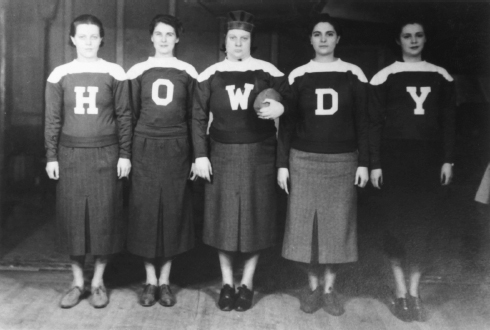

Vito Genovese's crews in Greenwich Village held the most interests in gay establishments in Manhattan going back to the 1930s. Genovese associate Steve Franse ran the Howdy Club at 47 West 3rd Street in Greenwich Village, the first nightclub catering to lesbians after they were outlawed by the NYSLA. It featured Blackie Dennis, a male impersonator, who dressed in tuxedoes and wore slicked-back short hair. “She was the best looking and most popular singer in the whole Village,” remembered a club regular. The club even did promotional photographs with women dressed in football gear. During the Second World War, sailors docked in New York went to the Howdy Club, some meeting other homosexuals in public for the first time.45

6–4: Promotional photograph for the Howdy Club, ca. 1935. Steve Franse ran the Howdy Club under Vito Genovese's Mafia crew in Greenwich Village. (Used by permission of the Lesbian Herstory Archives)

In 1943, the mob opened Tony Pastor's Downtown, which billed itself as “One of New York's Most Colorful Nite-Clubs.” Lesbians at the bar would send over drinks to attractive girls, and there were Sunday cocktail dances for women. The manager of Tony Pastor's Downtown was Joseph Cataldo. Behind the scenes, Joseph “Joe the Wop” Cataldo was a longtime mafioso under the Genoveses.46

Even the Cosa Nostra's power had its limits when the public's enmity toward “degenerates” required a crackdown. In 1944, the NYSLA suspended the license of the Howdy Club for presenting shows by Leon La Verdi, who “exhibited feminine characteristics which would appeal to any male homosexual.” Steve Franse argued that “La Verdi had been doing the same act for about 10 years without complaint.” It did not work, and the Howdy Club closed permanently. That same year, Joe Cataldo was found guilty of “permitting Lesbians to loiter on the premises,” resulting in the suspension of Tony Pastor's license. However, Tony Pastor's managed to reopen and remain in business until 1967, when the NYSLA revoked its liquor license for permitting “homosexuals, degenerates and undesirables to be on the license premises.”47

The 181 Club, 181 2nd Avenue

“The most famous fag joint in town,” screamed tabloid journalists pressuring officials to shutter its doors.48 Patrons and employees of the 181 Club saw their place differently. “It was like the homosexual Copacabana,” said Bertie, a tuxedoed waiter. As she described it,

it was a lovely club. Wedgwood walls, white and blue. It had a nice stage. They had the cream of the crop, as far as female impersonators. They weren't just drag queens. These were guys that had talent behind their costumes. The costumes were lavish and wonderful. They had borzoi…with rhinestone collars.49

“All the butches worked at this club as waiters and ‘Chorus Boys,’” a regular recalled. Buddy Kent performed there as Fred Astaire, with black tails, a top hat, and a cane. “It was showbiz, and very, very glamorous,” Kent recounted proudly. The audiences were a mix of gawking straight couples, closeted gays and lesbians, “and racketeers.”50

The Mafia kept open the doors of the 181 Club. Vito Genovese was once its hidden owner, and its manager was Steve Franse. Even during the height of the crackdown on gay life in New York, the 181 Club survived and prospered from 1945 to 1953. “The cops were paid off,” explained Buddy Kent.51

Mob-Owned Gay Bars in the 1950s

Franse ran the 181 Club from 1945 until 1953, when he moved it to 82 East 4th Street and renamed it Club 82. It became the most popular drag spot in the 1950s. Greta Garbo and Judy Garland were among the celebrities who attended shows at Club 82. Terry Noel, a female impersonator, did three shows a night, six nights a week, not getting off until 4:00 a.m. Noel said “the club owners had a certain influence over the vice cops, if you get my drift, and we were in less danger from them than the owners when it came to leaving in drag.”52

On June 19, 1953, Steve Franse left Club 82 at 4:30 a.m. to meet up with Pat Pagano and Fiore Siano. They wanted to see Joe Valachi's new restaurant in the Bronx. Valachi gave them a tour of his place, ending up in the kitchen. “That's when it happens,” Valachi describes:

Pat grabs [Franse] from behind—he has got him in an armlock—and the other guy, Fiore, raps him in the mouth and belly…. I'm standing guard by the kitchen door when Pat lets go and Steve drops to the floor. He is on his back, and he is out. They wrap this chain around his neck. He starts to move once, so Pat puts his foot on his neck to keep him there. It only took a few minutes.

Vito Genovese ordered the murder of Franse. Vito's wife Anna Genovese had sued Vito for maintenance and, to the shock of everyone, tried to identify his underworld assets. Anna was involved in nightclubs with Franse, and Vito blamed him for not keeping a lid on her.53

After Franse, Genovese caporegime Anthony “Tony Bender” Strollo took over the Genovese nightclubs in the Village. After Strollo disappeared in 1962, Tommy Eboli took over the family's bars and nightclubs in the Village. Later in the ’60s, Matthew “Matty the Horse” Ianniello, another Genovese caporegime, took interests in gay bars and pornographic bookstores in Times Square.54

Other mafiosi controlled gay bars elsewhere in New York. Edward “Eddie Toy” DeCurtis of the Gambino Family held interests in gay establishments on Long Island. In the 1960s, DeCurtis was convicted of allowing “lewd, indecent and disorderly homosexual activities” at his Magic Touch restaurant on Long Island. Anthony “Fat Tony” Rabito of the Bonanno Family “controlled a bunch of fag bars” in New York. And Salvatore “Solly Burns” Granello reportedly held hidden interests in gay bars on the East Side of Manhattan.55

Mafia Management of Gay Bars

With little competition, Mafia-run bars could charge high prices for lousy amenities. Most were hidden away on side streets, their windows painted dark, and they peddled watered-down, bootleg liquor supplied by mafiosi. “We would…take [brand label] bottles, and pour whatever swill we could get into it,” recounted Chuck Shaheen, a bartender at mob-run gay bars. Even at the glamorous 181 Club, the overpriced drinks were dismal. “The drinks were all watered, God knew what they were,” remembered a patron.56

The toxic arrangement with the police wrought indignities. To appease hostile neighbors, the police staged raids periodically. White lights would blink on when a raid was happening. Humiliated patrons stood in the harsh light of a dank basement before being hauled off in a paddy wagon. “If they took you in, it was usually for ‘disturbing the peace’ or ‘impersonating’ somebody of the opposite sex,” said Buddy Kent shaking her head.57

Starting in the 1950s, the Mattachine Society, the first gay-rights organization in New York, began criticizing the vice police and the Mafia itself. “The Mafia has been in the business for years,” charged Mattachine leader Richard Leitsch in 1967, “primarily because the legal setup has been such as to discourage legitimate business from operating [gay] bars.” Frustration with the mob system of bars culminated in a revolt that now symbolizes the gay rights movement.58

The Stonewall Inn, 53 Christopher Street

If the 181 Club was the gay Copacabana, then the Stonewall Inn was the dive bar. The Stonewall had no running water behind the bar, so its bartenders just dipped used glasses in a basin of dirty water, refilled the glasses, and served other customers. The toilets routinely overflowed, leaving the bathroom soaked. Like the 181 Club though, the Stonewall was operated by members and associates of the Genovese Family. Chuck Shaheen, who opened the Stonewall with its mob owners, said that Matthew “Matty the Horse” Ianniello was “the real boss, the real big boss.” Its bouncer Ed “The Skull” Murphy confirmed that Cosa Nostra made $1200 monthly payoffs to the NYPD's sixth precinct in exchange for letting the Stonewall operate without a liquor license, and tipping off its managers to planned raids.59

On June 28, 1969, that arrangement was disrupted by a raid executed by an honest vice cop. The historian David Carter has shown that Seymour Pine, the newly appointed commander of the local vice squad, was really after its mob owners for other crimes. “We weren't concerned about gays. We were concerned about the Mafia,” Pine maintained. This is supported by contemporaneous news accounts: “Police also believe the club was operated by Mafia connected owners,” reported the New York Daily News.60

This time, the drag queens fought back. “You already got the payoff, here's some more!” screamed Ray “Sylvia Lee” Rivera throwing pennies at the police. “Why do we have to pay the Mafia all this kind of money to drink in a lousy fuckin’ bar?” protested Rivera. “It wasn't my fault that the bars where I could meet other gay people were run by organized crime,” thought Morty Manford, a Columbia student who was at the Stonewall that night. By that Sunday, June 29, protestors handed out leaflets attacking “the Mafia monopoly.”61

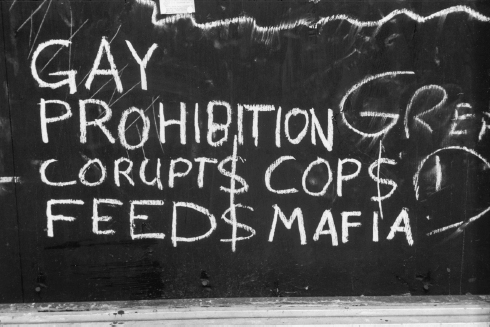

During the riots, someone wrote this graffiti on the Stonewall Inn's boarded-up windows:

GAY

PROHIBITION

CORUPT$ COP$

FEED$ MAFIA

And that informal haiku says it all.

6–5: Graffiti on Stonewall Inn, 1969. The outlawing of homosexuality meant that the Mafia controlled many of the gay and lesbian bars in New York City. (Photo by Fred W. McDarrah, used by permission of Getty Images)