I kept thinking of the mess I was in, and I couldn't help longing for the days when I was just a kid mouthpiece, making lots of money as a shyster in the magistrate's court.

—Mob lawyer J. Richard “Dixie” Davis (1939)

I have in mind that I was originally advised by Rosen that the Mafia or anything like it in character never existed in this country. I have been plagued ever since for having denied its existence.

—FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover (1970)

On the evening of Saturday, December 7, 1929, the Tepecanoe Democratic Club was throwing a dinner in honor of Magistrate Judge Albert H. Vitale at the Roman Gardens restaurant in the Bronx. Al Vitale had been a party hack before being appointed to the city magistrates’ court, which gave him jurisdiction over criminal proceedings. The fifty guests included not only an NYPD detective, criminal defense lawyers, and bail bondsmen, but also mafiosi Daniel Iamascia, Joseph “Joe the Baker” Catania, and his brother James Catania. It was just another evening among cronies in the Tammany Hall legal machine.1

Except on that night, other gangsters decided to crash the party. At 1:30 a.m., seven gunmen marched into the dining room and relieved the fifty guests of $5,000 in cash and jewelry.2 When news of the robbery—and Judge Vitale's sordid guests—hit the papers, the media frenzy forced a bar association inquiry into his links to gangsters. Vitale acknowledged being acquainted with Ciro “The Artichoke King” Terranova, whom he “regarded as a successful business man.” He also admitted receiving a $19,000 “loan” from none other than Arnold Rothstein (over $250,000 in 2013 dollars). In all, Vitale made $165,000 during his four years on the bench (over $2.3 million in 2013 dollars), which he attributed to “fortunate investments.”3

Following a trial on judicial misconduct charges, on March 13, 1930, the State Appellate Division removed Vitale from the bench. Yet Vitale thrived in his career as a private lawyer. During a federal trial in 1931, a witness testified that a gangster had bragged, “Vitale is my friend and can reach any judge in New York, even though he is not on the bench.”4

The Mafia families maintained their power by neutralizing law enforcement in New York. They started with payoffs to crooked cops and judges. When that did not work, mobsters turned to criminal defense lawyers, the so-called mouthpieces for the mob. The Cosa Nostra also flourished because the Federal Bureau of Investigation was on the sidelines during the mob's ascent. A recently discovered handwritten note by J. Edgar Hoover, along with accounts by FBI agents, may finally explain Hoover's position on the Mafia.

CROOKED COPS

As we have seen, the Mafia's first line of defense was corrupt cops. Not every cop was dishonest. But before the Mafia even existed, from the 1890s Lexow Committee hearings to the 1972 Knapp Commission report on police corruption, there was a tradition of bribe taking and extortion by the NYPD.5 The Cosa Nostra attained quasi-immunity from local police. “Wiseguys like Paulie [Vario] have been paying off the cops for so many years they have probably sent more cops’ kids to college than anyone else,” explained Lucchese family associate Henry Hill.6 When narcotics detective Robert Leuci tried to investigate Al “Sonny Red” Indelicato's crew, Leuci's sergeant came by with an ex-federal narcotics agents to warn: “These [Indelicatos] are good people, they've done the right thing before…. You better think about what you're doing.”7

Wiseguys were so entrenched in Gotham that even honest police were largely resigned to them. “During his police career, my father had known his share of mobsters. With his Bronx squad commanded pals, he often went to Joe Cago's [Joe Valachi's] Lido restaurant,” recalled the son of an honest Irish cop. Absent a murder charge, or case requiring inside information, “even honest cops, for the most part, looked the other way.”8 When NYPD detective Frank Serpico tried to break up a numbers shop, a Genovese Family caporegime intervened: “What kind of guy are you? There're other honest cops, but at least they honor the contracts,” said the goodfella.9

CORRUPTION IN THE COURTHOUSES

Even good cases against mobsters could die behind the scenes. In Chicago and Atlantic City, Al Capone and Enoch “Nucky” Johnson built ties to Republican political machines. In New York, the mob's links to labor unions and the Tammany Hall Democratic machine had a strong, if subtle influence on judges and the District Attorney's Office. Mafiosi Vince Mangano and Joe Bonanno had “political clubs” for a reason. “To be behind bars means one thing in his underworld society: You're in because you're stupid and you don't have any influence,” recounted James Horan, an investigator for prosecutors Thomas E. Dewey and Frank Hogan.10 “In those days we were practically immune from prosecution,” confirms Henry Hill. “See, the local politicians needed the rank and file of our unions…[and] we hardly had to worry about the courts, since Paulie [Vario] made judges.”11

The Kings County (Brooklyn) courthouse in South Brooklyn was especially compromised by organized crime. In the 1940s, state special prosecutor John Harlan Amen obtained the removal of a Brooklyn magistrate judge for bribery, and the forced resignation of the District Attorney William Geoghan. (Geoghan's replacement William Dwyer himself fell under suspicion for failing to convict Albert Anastasia).12 The Brooklyn courthouse's corruption continued through the 1960s. “Deals were made, cases sold—that courthouse was a marketplace, not a hall of justice,” said undercover detective Robert Leuci. “A defendant with money had a better than fifty-fifty chance of buying his way out of any kind of case.”13 Leuci built corruption cases for the United States attorney, including a bribery conviction of Edmund Rosner, a prominent defense attorney caught on tape paying cash for secret court documents.14

Even New York's old coroner's office, which employed the medical examiners who investigated causes of death, had corruption problems. “The coroner's office was an important one for a political machine to control. It was a place where a case could be fixed or disposed of early, before public outcry could build up,” explained coroner George LeBrun. A corrupt coroner could botch a case for others to exploit. “Even when a prosecutor went ahead and obtained an indictment, a skillful defense lawyer could make good use of the coroner's verdict in raising a question of reasonable doubt in the minds of a trial jury,” said LeBrun.15

The New York State Joint Legislative Committee on Crime conducted a study of felony arrests of organized crime figures between 1960 and 1970 in the courts around New York City. The study found that 44 percent of indictments against mobsters were dismissed before trial compared to only 11 percent of all indictments. Furthermore, of 536 organized crime figures arrested on felony charges, just 37 were sent to prison—less than 7 percent.16 The rap sheets of mafiosi typically have many charges, but relatively few convictions and little prison time. Before 1959, Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo was charged with felonies eleven different times, but he was convicted only once and spent a total of six months in prison. Alex Di Brizzi was arrested twenty-three times on charges ranging from bookmaking to felony assault, but he got away with fines and suspended sentences through 1958. We will never know how many of these cases were fixed.17

“MOUTHPIECES FOR THE MOB”: CRIMINAL DEFENSE ATTORNEYS

When all else failed, and a major felony was set for trial, mafiosi turned to criminal defense attorneys to talk them out of trouble. The New York bar had had criminal defense specialists since the notorious firm of Howe & Hummel was put on retainer by Frederika “Mother” Mandelbaum, Gotham's biggest fence.18 Starting during Prohibition, gangsters relied more and more on criminal defense lawyers or “mouthpieces,” as the goodfellas called them. These “mouthpieces for the mob” became essential to the New York Mafia.19

The Mob Temptation for Lawyers

Mobsters were unlike most clients. They often led intriguing lives on the edge of infamy. Defense lawyers knew the complications—and temptations—of representing gangsters.

Samuel S. Leibowitz was one of the finest criminal defense lawyers (and later federal judges) of the twentieth century. During Prohibition, he obtained acquittals of Al Capone and Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll among other gangsters. Although Leibowitz made no apologies for providing a zealous defense, he knew the hazards of representing gangsters. “The doctor uses all the skill and scientific knowledge at his command, yet takes every precaution not to become infected by the germs of his patient,” described Leibowitz. He expanded on his colorful analogy:

Figuratively speaking, I made it my business to don a “white gown” to avoid exposure to antisocial germs. The regrettable fact is that a few specialists in this field neglected to distinguish between their professional obligations and their social life and made the mistake of not wearing a “white gown” any of the time. At the end of the legal day's work they hobnobbed on intimate terms with their virulent clients and thus brought disgrace on themselves and dishonor on a noble profession.20

When Washington lawyer Edward Bennett Williams took on Frank Costello as a client, he was fascinated when Costello took him to the Copacabana and introduced him to celebrities and bookmakers. However, Williams learned to keep his mob clients at arm's length. “You need me. I don't need you,” he told them.21 Florida defense attorney Frank Ragano regretted getting too close to clients like mafiosi Carlos Marcello and Santo Trafficante. “My gravest error as a lawyer was merging a professional life with a personal life,” said Ragano. “I gradually began to think like them and to rationalize their aberrant behavior.”22

Mob Lawyers

Other lawyers crossed over the line from professional advocate to partners in crime. J. Richard “Dixie” Davis left a white-shoe law firm in Manhattan for the excitement of representing Harlem numbers runners, whose defenses were paid for by high-level gangsters. Davis was by all accounts an excellent defense attorney. “Davis was a very bright, imaginative, twisted-minded, young man,” said Thomas E. Dewey, who faced him in court. By thirty, Davis had turned himself into a leading defense lawyer and married a Broadway showgirl.23

Then Davis crossed the line between defending his clients in court and helping them run the Harlem numbers lottery. Davis began hanging out with his top client Dutch Schultz, a trigger-happy gangster with links to the Mafia. Late one night, in a cheap hotel room, Davis witnessed Dutch Schultz put a gun into the mouth of one of his underlings…and fire. “I was scared. It is very unhealthy to be an eyewitness to a murder when a man like Schultz is the killer,” said Davis. “I kept thinking the mess I was in, and I couldn't help longing for the days when I was just a kid mouthpiece, making lots of money as a shyster in the magistrate's court.”24

Dewey brought an indictment against Davis to pressure him to testify not only against the gangsters but also against Tammany Hall district leader James “Jimmy” Hines. Hines had been providing protection to the Harlem numbers lottery by telling judges he got appointed to dismiss charges against Schultz's men. “Davis was nothing but an expendable and replaceable young lawyer. They could have found another one of those, but Hines was at the top,” explained Dewey.25 Davis's testimony ultimately helped convict Hines. Though he avoided a long sentence, J. Richard “Dixie” Davis was disbarred in 1937, his legal career over at thirty-two.26

Other attorneys dashed across the line to criminality. Frank DeSimone was literally a mob lawyer. He graduated from the University of Southern California School of Law in 1932, passed the bar, and practiced law in Los Angeles for the next twenty years. In that time, DeSimone quietly rose to become boss of the Los Angeles Mafia family. DeSimone developed contacts with the Lucchese Family of New York, and was called “the lawyer” by informants.27

Criminal defense attorney Robert Cooley became enmeshed in the world of the Chicago Outfit in the 1970s and ’80s. Mobsters called Cooley “the mechanic” for his ability to fix cases. “For the first eleven years of my legal career, almost every day I gave out bribes—and not just to judges,” admitted Robert Cooley. He started socializing with mobsters, too. “Four times, I shared a last meal with a gangster before he went off to his death. Each one was calm and unsuspecting,” Cooley recounted. Sickened by the violence, Cooley became an informant for the government and testified as a witness against dozens of mobsters.28

Defense Lawyer Tactics: Playing the Identity Card

Most criminal defense attorneys did their work within the bounds of the law and were unrepentant about providing a zealous defense. Asked how he could represent accused mobsters, Bobby Simone cites the defense lawyer's creed: “The simple answer—the presumption of innocence owed every criminal defendant and the proposition that no one is guilty until and unless a jury, or in some cases a judge, says so after a fair trial.”29 Others argued that they were defending constitutional rights. “Strike Force attorneys and FBI agents acted like they were doing God's work, and therefore didn't have to play by the rules,” argued Las Vegas mob lawyer (and now mayor) Oscar Goodman. “That's not what the Constitution says, nor is it what the Bill of Rights is about.”30

The defense lawyer's tactics were not always pretty. A favorite tactic of some was playing the ethnic-identity card. Italian immigrants had often been grotesquely attacked as criminals by the press and politicians. The largest mass lynching in American history took place in 1890 in New Orleans when eleven Italians were hung by a mob after their acquittals and mistrials on charges of assassinating police chief David Hennessy. Modern defense lawyers, however, tried to portray hardened, wealthy mafiosi as nothing more than innocent ethnic martyrs. After a meeting of the Mafia was discovered in Apalachin, New York, in November 1957, attorneys for the mob attendees played the ethnic card aggressively.31 During the trial of the Apalachin attendees, the defense made this a central theme. “All these men are Italian. Is that why they are here in this courtroom?” asserted a defense lawyer at trial. “What's on trial here? The Sons of Italy?” another lawyer asked rhetorically.32

Mob front groups used similar tactics. In 1960, a member of an “Italian-American service organization,” identified as “William Bonanno, a wholesale food distributor from Tucson, Ariz.,” condemned the “stereotyping of Italian-Americans as gangsters,” which he said was “causing financial, social and moral damage to the whole Italian-American community.” Bonanno, the “food distributor,” was in fact a gangster who later peddled memoirs romanticizing his life in the Mafia.33

Criminal defense lawyers and mob front groups put the Department of Justice on the defensive with accusations of anti-Italian bias. “In the 1960s and 1970s, after we publicly entered the battle, the FBI was constantly attacked as being anti-Italian because of our efforts to break La Cosa Nostra,” said FBI agent Dennis Griffin. “Defense attorneys attacked me personally with this charge when I was on the witness stand testifying against Mob leaders.”34 Mafia boss Joseph Colombo formed the “Italian-American Civil Rights League” to protest outside the Manhattan office of the FBI. “Mafia, what's the Mafia?” said Colombo. “There is not a Mafia.” Cowed by the protests, Attorney General John Mitchell barred the Department of Justice from using the words “Mafia” and “Cosa Nostra.”35 Not everyone bought it though. State senator John Marchi denounced the Civil Rights League, saying, “Italian-Americans have been had.”36

Defending the Constitution

Other times, the mob's lawyers were defending important constitutional protections. After the media turned Frank Costello into a high-profile target, the police ran nonspecific, twenty-four-hour wiretaps not only on his home telephone, but on all pay phones in restaurants he frequented. Police then transcribed the conversations on the phones, whether Costello was a participant or not. Costello's attorney, Edward Bennett Williams, who read hundreds of these transcripts, explained the Fourth Amendment problems with this. “Husband-and-wife calls were monitored. The tender words of sweethearts were heard by a third ear. In short, hundreds of wholly innocent, law-abiding and unsuspecting citizens were deprived of their right to communicate privately,” recounted Williams. As Costello's attorney, Williams spent years challenging this and other due process issues, culminating in two appearances at the Supreme Court.37

Perhaps the most interesting legal quandary was the 1959 case against the Apalachin attendees. Dozens of high-level mobsters were caught in upstate New York at what we now know was a crucial meeting of the Cosa Nostra. The mafiosi were not there just for a barbeque. But prosecutors could not get any of the wiseguys to flip and testify about the criminal aims of the meeting. Nonetheless, a federal jury convicted them on an attenuated theory of conspiracy. The Court of Appeals reversed on the ground that the government had not met its burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. The Court was troubled by the theory of the case. As one of the judges pointed out, “The indictment did not allege what the November 14, 1957 gathering at Apalachin was about, and the government stated at the beginning of the trial could it could present no evidence of its purpose.”38

Most defense lawyers for the mob were simply asserting guarantees of the United States Constitution, which provides more robust protections and due process rights for the accused than any other written constitution. Mobsters certainly recognized its importance. After he was deported to Italy, Charles Luciano complained about how Italian police once held him for eight days without a formal charge. “It couldn't happen in the good old days in New York. My lawyer woulda had me out on bail inside forty-eight hours. These people don't know what the word bail means,” said Luciano.39

RECORD ON THE MAFIA: LOCAL FAILURE vs. STATE AND FEDERAL SUCCESS

Perhaps the clearest sign of the paralysis of local law enforcement is comparing its weak record to that of state and federal law enforcement. With few exceptions, the most significant and effective crackdowns on early mafiosi were carried out by federal or state officials.

The Morello Family was decimated by the United States Secret Service, not by the NYPD. Al Capone was brought down by the United States Treasury Department's tax unit, not by the Chicago police. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics obtained far more convictions of New York Mafia drug traffickers than the local narcotics unit. The 1957 Apalachin meeting was uncovered by the New York State Police and the Treasury Department's Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Unit.

Even “local” officials who attacked the mob had first built up a political base in federal or state appointments. Before Thomas E. Dewey was elected Manhattan district attorney in 1937, he was the assistant United States attorney who obtained convictions of Waxey Gordon, and a state special prosecutor who convicted racketeers. Likewise, before Rudolph Giuliani became mayor, he oversaw federal prosecutions of the Mafia as the United States attorney for the Southern District of New York.40 This comparison is all the more impressive considering that the premier federal investigative agency was on the sidelines.

DIRECTOR HOOVER'S FBI, 1924–1957: HOOVER'S REFUSAL TO ACKNOWLEDGE THE MAFIA

The Mafia families were fortunate that the Federal Bureau of Investigation was not actually investigating them. For his first thirty-three years as FBI director, between 1924 and 1957, J. Edgar Hoover took few sustained actions against the Mafia. Indeed, Hoover refused to publicly acknowledge its existence.

Conspiracy theories have sprung up claiming Hoover was compromised by organized crime. In his bestseller Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover, Anthony Summers offered lurid stories of J. Edgar Hoover dressed in drag at Washington parties. He claimed that Meyer Lansky blackmailed the director with a photo of him in a dress.41 Summers's primary “witness” was Susan Rosenstiel, who had a conviction for attempted perjury, and who for years had been trying to sell her story for money.42 The story is absurd. Hoover would have been ousted had he been going to Washington parties in drag in the 1950s. Mobsters of that era dismiss the story. “Are you nuts?” said Vincent Alo, a partner of Lansky. “There was never no such picture. If there was, I'd have known about it, being so close to Meyer.”43

The truth about Hoover's reluctance is more complex, but ultimately more fascinating. A recently released FBI document of Hoover himself sheds new light on his beliefs. To understand the document, and Hoover's position on the mob, we need to understand the man and his times.44

Hoover's Overarching Purpose: Rooting out Spies and Subversives

Jay Edgar Hoover's top priority, his raison d’être, had always been rooting out spies and “subversives” from America. As a young special assistant to Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, Hoover enthusiastically planned raids on anarchists during World War I.45 When Hoover was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation in 1924, he professionalized the scandal-ridden agency by reforming hiring and standardizing its procedures. He also expanded intelligence gathering on “subversives” like Socialist writer Theodore Dreiser. In 1929, Bureau agents even ransacked the New York office of the American Civil Liberties Union.46

Hoover was not always chasing ghosts though. During World War II, the FBI captured Nazi spies and saboteurs, and it began tracking secret agents of the Soviet Union. In 1943, the FBI recorded a Soviet diplomat paying a leader of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) to develop intelligence on the Manhattan Project to build the atomic bomb. In 1947, the National Security Agency disclosed to FBI officials that under its “VENONA project,” NSA cryptologists had decoded messages indicating that Soviet espionage had penetrated the United States government.47

During the Cold War, Hoover turned the FBI into more of an internal security ministry than a law enforcement agency. He poured resources into counterintelligence indiscriminately, and he dangerously blurred the line between actual enemies of the state and political dissidents. These remained the FBI's top targets through the 1950s, even after the CPUSA had been decimated.48 Hoover had FBI agents assembling dossiers on teachers. “The bureau was sending raw and confidential file material on the suspected Communist activities of teachers to local school boards throughout the country,” said Attorney General Herbert Brownell, who stopped the practice.49

Hoover's tunnel vision came at a cost to other FBI functions. Even after anticommunists like Robert F. Kennedy and Senator John McClellan had expanded their attention to organized crime and racketeering in the 1950s, Hoover continued to obsess about the remnants of the CPUSA. As late as 1959, the FBI's New York field office had only 10 agents assigned to organized crime compared to over 140 agents pursuing a dwindling population of Communists.50 As a result, the FBI lacked adequate intelligence on the Mafia.

The Rise of the Mafia and the Kefauver Committee

By contrast, Hoover resisted investigating the “hoodlums,” as he called them. Given that the Constitution left most police powers to states and cities, the FBI's role regarding crime was unclear. Hoover declared his opposition to a “national police force” early on, and he lambasted corrupt cities where “the local officer finds the handcuffs on himself instead of on the criminal, because of political influence.”51 His position initially had much support among commentators and Congressmen.52 The Senate was controlled by state-rights politicians or segregationists like Strom Thurmond who disliked federal officers interfering in “local” matters.53

But Hoover was a federalist when it suited him. He exploited high-profile crime issues to increase funding for the FBI. In 1933–34, Hoover seized on the public clamor over Midwest bank robbers John Dillinger and Pretty Boy Floyd to lobby Congress to pass federal laws covering traditionally local crimes like bank robbery, kidnapping, automobile theft, and transportation of stolen property across state lines. According to one civil rights lawyer, “[Hoover] would say one day, ‘We are not a police agency.’ The next day for a bank robbery, kidnapping or auto theft, he would be a police agency. When it came to the Mafia or narcotics, ‘We're not a police agency.’”54 While Hoover was trumpeting questionable statistics about automobiles recoveries by the FBI, the bulk of new agents were assigned to gathering intelligence on subversives.55

As organized crime grew in strength, however, local officials began requesting assistance from the Department of Justice and the FBI.56 In March 1949, the head of the Crime Commission of Greater Miami (a second home to many New York mafiosi) warned that “the influence of the national crime syndicate is so great that where the group has rooted itself, law abiding citizens and officials are silenced either through wholesale corruption or through threats and intimidation.”57 In 1949, an organization of mayors wrote to the new attorney general Howard McGrath, stating, “The matter is too great to be handled by local officials alone, since the organized crime element operates on a national scale across State boundaries.”58 McGrath held a crime conference but did little else. McGrath and Hoover were reluctant to get the FBI involved in what they thought was purely “local” vice crime. However, McGrath and Hoover were largely ignorant of the Mafia families, their cross-country networking, and their substantial effects on interstate commerce.59

Then, in April 1950, Kansas City mobsters Charles Binaggio and Charles “Mad Dog” Gargotta were found murdered in a Democratic Party club. (Binaggio was boss of the Kansas City Mafia with links to the governor). The Kansas City Star identified Binaggio as a “local representative of the national crime syndicate.” The Star called on “J. Howard McGrath and J. Edgar Hoover, head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation…to investigate and ‘break’ this syndicate.”60

These calls fell on deaf ears. On April 17, 1950, Attorney General McGrath testified before a Senate subcommittee that the Justice Department had “no evidence” of “any great national (crime) syndicate of any size.” In response, Senator Homer Capeheart called the statements “surprising.” He said that “either there is or there isn't a nationwide syndicate,” and that “the Attorney General should know about it.”61 McGrath, who'd only been in office eight months, was clearly relying on Hoover's FBI.

So instead, Senator Estes Kefauver seized the issue to secure limited (in retrospect inadequate) funding for Congressional hearings on organized crime in 1950–51. With a small staff of twelve investigators, and no real assistance from the FBI, Kefauver tried to prove the existence of the Mafia in hearings around the country. The Kefauver Committee hearings were a television sensation, with over six hundred witnesses, including such gangsters (and secret mafiosi) as Frank Costello, Carlos Marcello, Willie Moretti, and Paul Ricca.62

But the committee staff was overwhelmed, and they could not get an informant to testify publicly about the Mafia. “The committee found it difficult to obtain reliable data concerning the extent of Mafia operation, the nature of the Mafia organization, and the way it presently operates,” admitted the committee.63 “The committee has diligently, but unsuccessfully, pursued the trail of the Mafia,” wrote the New York Times.64 Nonetheless, as politicians are wont to do, Kefauver exaggerated his findings. For example, he claimed that “the Mafia today actually is a secret international government-within-a-government. It has an international head in Italy—believed by United States authorities to be Charles (Lucky) Luciano.” Although Luciano had been a New York boss, by 1951 he was idling in exile, and he certainly was not the “international head” of a “secret international government-within-a-government.”65

To Hoover, the parade of hoodlums was a distraction from the Communists. It shows in his testimony before the Kefauver Committee on March 26, 1951. That same morning, a federal jury in Manhattan was hearing evidence in the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for conspiracy to commit espionage, which Hoover would dub the “Crime of the Century.”66 In his testimony, Director Hoover never acknowledges the Mafia's existence. While witnesses from the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and the Justice Department repeatedly reference “the Mafia,” Hoover conspicuously avoids the word, instead dismissively referring to “hoodlums.”67 Hoover lectured the senators, saying that local authorities were responsible for hoodlums, while the FBI was responsible for “internal security” against “Communists and subversive forces.”68 In fact, Hoover cited his top priority (national security) in the process of turning down new FBI jurisdiction to go after organized crime:

| Senator Wiley: | Do you think it would help some in this country if your jurisdiction were extended? |

| Mr. Hoover: | I do not. I am very much opposed to any expansion of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. I think it is too big today. We have had to take on additional duties and responsibilities…because of the national security.69 |

Due in part to his own intransigence, Hoover got his way, and Congress passed no new federal laws for the FBI. The Mafia emerged unscathed, again.

Hoover's Disbelief in the Mafia

This brings us to the heart of the matter. Most theories about Hoover's inaction assume that he “must have known” about the Mafia's existence, but that he dissembled because he did not want to pursue it. A recently released FBI document and firsthand accounts by FBI agents point to another reason. Simply put, Hoover genuinely did not believe in the existence of the Mafia.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation had virtually no intelligence on the Mafia families, the largest crime syndicates in the United States, through the late 1950s. FBI Boston field agent Neil Welch remembers his fellow field agents circulating the Federal Bureau of Narcotics's lists of mafiosi because the FBI kept no such information.70 As FBI Chicago field agent William Roemer observed, “Mr. Hoover had no knowledge of organized crime in the United States because except for a ‘special’ such as CAPGA (code name for ‘reactivation of the Capone gang’) in Chicago, which lasted just a few months in 1946, the Bureau had never investigated organized crime.”71 This deprived Hoover of even basic intelligence on the Cosa Nostra. There is no evidence that Hoover knew about the Commission or understood its interstate connections. There is no evidence that Hoover knew of the existence or structure of the five Mafia families of New York. In fact, between 1924 and 1957, the director of the FBI never publicly uttered the word “Mafia” or “La Cosa Nostra.”

The FBI's intelligence failure was exposed by its flat-footed response to news that dozens of mafiosi were caught meeting at Apalachin, New York, on November 14, 1957 (see chapter 10). When a Senate committee asked the FBI for intelligence on the attendees, the FBI had little to provide. “The FBI didn't know anything, really, about these people who were the major gangsters in the United States,” recounted Robert Kennedy, counsel to the Senate committee. “I sent the same request to the Bureau of Narcotics, and they had something on every one of them.”72 In the weeks after Apalachin, FBI officials were still denying the existence of the Mafia. On November 21, 1957, a reporter quoted an “unimpeachable source” within the FBI pooh-poohing the idea of a Mafia, saying “nothing of any substance has ever been shown in this respect, nothing has even come close to doing so.” Remarkably, the source acknowledged that “the FBI never has investigated the Mafia.”73 As late as January 8, 1958, an internal FBI report stated: “No indication that alleged ‘Mafia’ is an actual and existent organization in NY area, but is convenient term used to describe tough Italian hoodlum mobs.”74

FBI officials under Hoover have since come forward to talk about the director's blind spot regarding the Mafia. “‘They're just a bunch of hoodlums,’ Hoover would say. He didn't want to tackle organized crime,” confirms William Sullivan, former third-in-command of the FBI.75 Or as former assistant FBI director Cartha “Deke” DeLoach explained:

His profound contempt for the criminal mind, combined with his enormous faith in the agency he had created, persuaded him that no such complex national criminal organization could exist without him knowing about it. He didn't know it; ergo it did not exist.76

FBI official Oliver “Buck” Revell recalled an extraordinary conversation that he'd had with Director Hoover on February 8, 1971. Hoover was welcoming Revell to his role heading up a new FBI assault on the Cosa Nostra. After some pleasantries, Hoover became reflective on his disbelief in the Mafia's existence. “We didn't have any evidence,” Hoover insisted. “Not until they held that hoodlum conference up in Apalachin, New York, back in ’57.”77

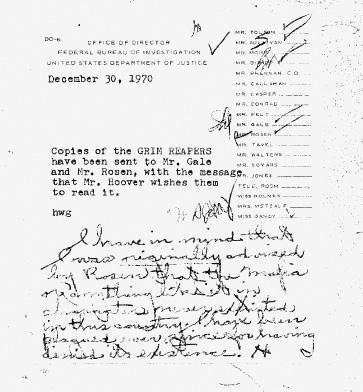

These accounts can now be corroborated by the written words of Hoover himself. On December 30, 1970, Hoover sent an interoffice memorandum to his deputies asking them to read Ed Reid's 1969 book on the mob, The Grim Reapers.78 Hoover handwrote a revealing note at the bottom. The document reads:

December 30, 1970

Copies of the GRIM REAPERS have been sent to Mr. Gale and Mr. Rosen, with the message that Mr. Hoover wishes them to read it.

hwg [Secretary Gandy].

I have in mind that I was originally advised by Rosen that the Mafia or anything like it in character never existed in this country. I have been plagued ever since for having denied its existence. H79

The “Rosen” to which the director referred in his note was Alex Rosen, assistant director of the General Investigative Division for thirty years under Hoover.80 Although Hoover may have been blaming Rosen unfairly, the note gives us a rare glimpse into Hoover's thinking on the Mafia. At some point, Hoover believed that “the Mafia or anything like it in character never existed in this country,” and he therefore “denied its existence.” He regretted his stance, feeling “plagued ever since” for his longstanding position.

Still, how could Hoover have doubted the existence of the Mafia for so long? The Federal Bureau of Investigation should have investigated stories corroborating the existence of the Mafia far more seriously. “It's inexcusable for them to say they couldn't have been using that [intelligence] function to at least be aware of what the hell is going on,” said William Hundley, a top lawyer in the Justice Department.81 Nor is it satisfactory to blame Senator Kefauver's flawed hearings, as some have suggested, for the FBI director's refusal to acknowledge the Mafia. It is preposterous to expect Senate staff to prove a crime syndicate to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Had Hoover used some of the FBI's intelligence function to investigate the Mafia, it might have supplied the Kefauver Committee with the sources it needed. At a minimum, Hoover could have given more informative responses. Take the fine answer of a Bureau of Narcotics agent in 1957 to a Kefauver-inspired question about an international “head of the Mafia”:

| Senator Ives: | I am curious to know where the head of the Mafia is today. What country? Sicily, still? |

| Mr. Pera: | Well, a study of their organization, as it exists, would indicate to us that it is a loose organization, that there is no autocracy in it, that it is composed of a group of individuals who discuss with each other what is mutually beneficial to them and come to agreement on lines of action that is mutually acceptable to them.82 |

8–1: Handwritten note of J. Edgar Hoover, 1971. (Courtesy of the Federal Bureau of Investigation)

Or take J. Edgar Hoover's own later description in January 1962: “No single individual or coalition of racketeers dominates organized crime across the nation. There are, however, loose connections among controlling groups in various areas through family ties, mutual interest, and financial investment.”83 Or in September 1963, when Hoover explained that the Cosa Nostra was “a strong arm of organized crime in America” but that there was other organized crime, too.84

In fairness to Hoover, doubting the Cosa Nostra's existence was not a lunatic position in the 1950s. Before the Apalachin meeting and mob soldier Joe Valachi's public testimony of 1963, before the later flood of Mafia prosecutions (and even after), many people doubted the existence of the Mafia. “Regardless of what anyone else may say on the subject, there is no Sicilian Mafia, or simply ‘Mafia’ in the United States,” declared the historian Giovanni Schiavo on November 16, 1957, days after the Apalachin meeting.85 When FBI witness Joe Valachi testified before a Senate committee in 1963, he was attacked and belittled not only by fellow mafiosi, but by criminologists as well. In a 1969 essay titled “God and the Mafia,” the criminologist Gordon Hawkins mocked Valachi's testimony, claiming that evidence of the Mafia is “on examination to consist of little more than a series of dogmatic assertions.”86 But Valachi was a legitimate mafioso whose testimony was mostly right, and the esteemed criminologist was mostly wrong. Indeed, Valachi's testimony had already been thoroughly corroborated by multiple sources by 1969.87 Simply put, Mafia skeptics could not (or would not) accept that there were secret alliances of “families” dedicated to lives of crime and bound by common rituals and practices that operated in the United States.

But enough about Hoover. Let us look at the events in the Mafia that changed his mind: the events of 1957, the mob's terrible year.