The Volcano.

—Joe Bonanno on New York in the 1950s, A Man of Honor (1983)

They had been hunting Frank Costello at night. On the evening of Tuesday, April 30, 1957, Costello, the boss of the Luciano Family, was out on the town with his pals Anthony “Little Augie Pisano” Carfano and Frank Erickson. That same night, a police detective was conducting surveillance at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in an unrelated matter when he recognized Costello walking into the hotel bar.

The detective then spotted something else: two other men were surreptitiously trailing Costello's party. The lawman decided to keep an eye on them. When Costello left the Waldorf Astoria to stroll around midtown Manhattan, the two suspicious men were following him again from a distance. The police detective did not have enough to go on though, so he filed the observation away in his memory. Within days, the detective would learn the full implications of what he had seen.1

In the spring of 1957, the New York Mafia was fat, prosperous, and growing. The Mafia families controlled key union officials and held influence over businessmen in major industries. They were the top crime syndicates in Gotham, and they were the dominant heroin traffickers in America.

By Thanksgiving 1957, the Cosa Nostra would be in disarray. Internal conflicts would erupt into the public at a level unseen since 1931. Two Mafia bosses would be violently deposed, an underboss murdered while grocery shopping, and the wiseguys exposed to new scrutiny. Nineteen fifty-seven was to be the mob's annus horribilis.

Drawing on previously unpublished sources, this chapter re-creates the Mafia assassinations of 1957 and explores the underlying causes of the conflict. The unraveling of the mob leadership in the fifties revealed flaws present since the origins of the modern Mafia.

THE HUNTING OF A MOB BOSS: FRANK COSTELLO AND VITO GENOVESE

The men hunting Frank Costello were sent by his own underboss, Vito Genovese. He was a treacherous man to have as an underboss. He had little hesitation about arranging the deaths of mafiosi he had known for decades. Genovese soldier Joe Valachi testified before Congress that he executed hits on Steve Franse and Eugene Giannini on the direct orders of Vito Genovese. Genovese tried justifying his role in the 1951 murder of Willie Moretti, the longtime underboss of the Luciano Family, who the Commission thought was talking too openly about the Mafia. “It was supposedly a mercy killing because he was sick,” Valachi recounted. “Genovese told me ‘The Lord have mercy on his soul, he's losing his mind.’”2

Vito Genovese could make deals with anyone—and then promptly double-cross them. Take Genovese's machinations with Fascist Italy during the Second World War. Genovese plied Fascist officials with enormous cash tributes amounting to $250,000. He even received a personal decoration from the dictator Benito Mussolini. After the Axis powers fell, Genovese weaseled his way into the confidences of the United States Army occupation authorities. He promptly betrayed their trust by becoming a black marketeer of diverted American gasoline supplies.3

Because of Genovese's ruthlessness, stories arose whenever people died around him. For example, rumors swirled when Genovese married Anna Vernotico on March 30, 1932, only two weeks after her first husband Gerard Vernotico was found murdered. “Associates believed Vito had her husband strangled to death so that he could marry her,” writes Selwyn Raab in his book Five Families. Left out of the story is that a New York court had already granted Anna's petition for a divorce in January 1932, which was due to become a final judgment ninety days later in April 1932. Genovese would have been risking a murder charge to save a few weeks. In fact, Genovese was not a suspect in the case. Rather, the police believed that Gerard Vernotico, a gangster with a lengthy record, was killed by other racketeers.4

Genovese has also been blamed for the death of Pete LaTempa, a witness in the homicide case against Genovese for the 1934 murder of Ferdinand Boccia. LaTempa died from a drug overdose while in protective custody on January 15, 1945. “The city medical examiner reported that the pills LaTempa swallowed were not the prescribed drugs and contained enough poison to ‘kill eight horses,’” asserts Raab. This is not accurate. The toxicology report found prescription barbiturates in his system. Investigators discovered that LaTempa had received a prescription (from a doctor with the district attorney's office) for Seconal—a barbiturate. Moreover, LaTempa had previously attempted suicide by hanging on December 6, 1944. Based on this evidence, the district attorney ruled LaTempa's death a suicide. In short, Vito Genovese's record is sordid enough without repeating demonstrably inaccurate stories.5

Vito Genovese moved on Costello in the spring of 1957 after sensing the boss's vulnerability. The sixty-six-year-old Frank Costello had grown tired of the mob's street operations. Costello once boasted of knowing “the better people and nothing but the better. I know some of the biggest utility men, some of the biggest businessmen in the country.”6 The “better people” apparently did not include the caporegimes in his mob syndicate, with whom Costello had weak relations.7

The mob boss was having personal problems as well. He had suffered through recurring bouts with throat cancer, which turned his voice gravely. In the late 1940s (long before The Sopranos invented a mob boss in therapy), Frank Costello was seeing a psychiatrist in Manhattan.8 His disastrous testimony before the Kefauver Committee in March 1951, televised to a national audience, made him a target of law enforcement. In 1954, Costello was convicted of federal income tax evasion. His lawyers would spend years trying to overturn his conviction while he was out on bail.9

9–1: Frank Costello, testifying before the Kefauver Committee, 1951. (Photo by Al Aumuller, courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, New York World-Telegram and Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection)

11:00 p.m., Thursday, May 2, 1957, 115 Central Park West, Manhattan: The Attempt on Frank Costello

On the evening of Thursday, May 2, 1957, Frank and his wife Loretta went to see friends at the elegant L'Aiglon Restaurant. The dinner party included Mr. and Mrs. Al Miniaci, president of Paramount Vending, with whom Costello did business; Mr. and Mrs. Generose Pope, the publisher of Il Progresso, the Italian-language newspaper of which Costello was a longtime backer; and William Kennedy, owner of a modeling agency. After dinner, the group strolled down East 55th Street to the Monsignore Restaurant, where they met up with Frank Bonfiglio, a Brooklyn businessman who Costello had known for decades.10

Despite his good spirits, Costello's legal problems were weighing on him. He placed a call at about 10:45 p.m. to a Philadelphia lawyer. Frank returned to the table to apologize for having to leave early; he would be taking an 11:00 p.m. telephone call at home from his Washington attorney. His wife Loretta wanted to stay. So Costello left with Mr. Kennedy in a taxicab bound for the Upper West Side.11

At about 10:55 p.m., the taxicab arrives at Costello's upscale co-op apartment complex overlooking Central Park. The boss gets out of the cab and walks into the building's lobby. Then, a black Cadillac pulls up behind the parked cab. A hulking thug gets out of the Cadillac and rushes into the lobby.12

“This is for you Frank!” he shouts. Costello reacts, turning toward the shout. In a split second, a freakish bullet grazes the skin beneath Costello's right ear, furrows under the hair of his scalp, and exits, smashing into the marble wall of the foyer. Feeling a sting and the blood pouring down his neck, Costello staggers to the leather couch in the lobby. “Somebody tried to get me,” Frank cries. The doorman and William Kennedy then took him to Roosevelt Hospital.13

Don Vito Rallies the Caporegimes

The gunman's macho shout may have saved Costello's life. The doctors who treated his wound at the hospital concluded that Costello had turned his head at the very last moment. So instead of the bullet shattering his skull, Costello walked away with a flesh wound.14

According to underworld sources, the gunman who botched the assassination was twenty-nine-year-old Vincent “The Chin” Gigante, a husky former boxer who had become a mob soldier for Genovese. “The Chin wasted a whole month practicing,” mocked Joe Valachi, a fellow hit man for Genovese.15 The NYPD believed that Thomas Eboli, a caporegime close to Genovese, was driving the getaway car. Tommy Eboli's company put up $76,000 ($500,000 in 2013 dollars) as collateral for Gigante's bail.16

Rather than trying to deny he was behind it, Vito Genovese proceeded to stage a coup d’état in the Luciano Family. The rank and file had little affection for their absentee boss. For all of Costello's ease around New York's power brokers, Genovese better understood that the real power in the mob was in its street crews. So while Costello was out hobnobbing with celebrities and politicians, Genovese was building loyalty among the caporegimes.

Genovese tested that loyalty in the days following the botched attempt. “Vito called a meeting of all his lieutenants to condone his attempt on Costello's life,” describes an FBI report. “All of the lieutenants showed up at the meeting except Augie Pisano.”17 It was an impressive show of strength. “After the Costello shooting, his Family rallied around Genovese,” confirms Joe Bonanno. Genovese then made his move: “Don Vito” proclaimed himself boss of the Luciano Family and named Gerardo “Gerry” Catena as his underboss.18

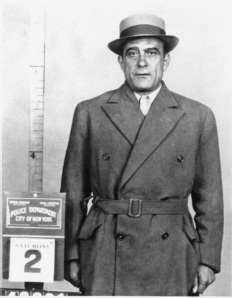

9–2: Vito Genovese, ca. 1934. (Courtesy of the New York Police Department)

Genovese and his soldiers braced for retaliation. The man they feared the most was Albert “The Executioner” Anastasia, who was furious about the attempt on his longtime ally Costello. Anastasia polled the Commission to see if it would remain neutral if he went after Genovese. The Commission's members warned Anastasia that they would oppose him if he turned it into a wider conflict. They persuaded him to stand down.19

The Trial of Vincent Gigante

Frank Costello had had enough of the mob life. He was already preoccupied with his own legal and health problems. Waging a prolonged fight against Genovese was unpalatable. He decided to retire as boss.20

Although police detectives believed that Costello had seen the gunman's face, he was completely unhelpful to their investigation. Costello insisted that he never had “an enemy in the world.” In response, a detective quipped, “Whoever this guy was, he had a very strange way of showing his friendship.”21

The following year, in May 1958, Vincent “The Chin” Gigante went on trial for the attempted murder of Frank Costello. Gigante's criminal defense attorney Maurice Edelbaum exploited Costello's unwillingness to identify the shooter:

“Do you know any reason why this man should seek your life?” Edelbaum asked.

“None whatsoever,” replied Costello.

….

“Tell us the truth,” Edelbaum demanded in theatrical fashion. “Who shot you?”

“I'll ask you who shot me,” Costello replied with a sly smile. “I don't know. I saw no one at all.”

The victim had rendered himself useless as a witness.22 That left the building doorman as the sole eyewitness to identify Gigante. Unfortunately, the star witness was completely blind in one eye and impaired in the other. Edelman destroyed the doorman's testimony on cross-examination.23

Shortly before midnight, the jury returned its verdict: not guilty. Loud applause broke out in the gallery; the defendant's wife Olympia and four children burst into tears.24 When the cheering stopped, Gigante was released by the court. The Chin walked over to Frank Costello, who was sitting in the back of the gallery. “Thanks, Frank,” said Gigante.25

The Luciano Family was not the only one of the original five families wracked with strife during the 1950s. Even more severe problems were stirring in the old Mangano Family.

MOB PATRICIDE: VINCENT MANGANO AND ALBERT ANASTASIA

By 1951, Albert Anastasia had been the underboss to the Mangano Family for twenty years. The young Umberto Anastasio had come up under the tutelage of Vincent and Philip Mangano. Albert the Executioner was their enforcer on the waterfront, and he was underboss to their mob family. Albert once said that Vince Mangano was “like a father to him.”26

After decades as their underboss though, resentments had arisen. Anastasia's ambitions were frustrated by the long tenure of the Mangano brothers. He was having a difficult time masking his contempt for Vince Mangano. “He always keeps surprises in store,” Anastasia sarcastically told a guest of his boss. For his part, Mangano was distrustful of Anastasia's close alliance with Frank Costello. “Mangano and Anastasia were at a stage where they feared one another,” recalled mob boss Joe Bonanno.27

Vincent Mangano went missing in early spring 1951. Then, on April 19, 1951, the bullet-riddled corpse of his brother Philip Mangano turned up in a marsh in Brooklyn. The police sought to question Anastasia and his associates about the gangland-style hit. But nobody was talking to the police. The homicide of Phil Mangano was never solved. Vince Mangano's body was never even found.28

The Commission wanted to know what happened to Vince Mangano. He was after all one of the original charter members. The Commission summoned Anastasia to a meeting. “He neither denied nor admitted rumors that he was behind Vincent's disappearance,” recalled Joe Bonanno, a Commission member. “However, he said he had proof that Mangano had been plotting to kill him” and that “if someone was out to kill him, then he had the right to protect himself.” His ally Frank Costello, as boss of the Luciano Family, backed up Anastasia's version of events before the Commission. Their message was clear enough. The Commission was not about to challenge them.29

Vince Mangano had never been pure in these matters anyway. In April 1931, Mangano betrayed his boss Joe Masseria by joining Salvatore Maranzano. Then, after Maranzano's assassination in September 1931, Mangano became boss of the Brooklyn waterfront by pushing aside Frank “Cheech” Scalise.30 It was not exactly a pristine rise to power.

The flaw was present in the Mafia since the very beginning. The Mafia families were well-structured to allow their members to make money. The Commission provided a forum to arbitrate ordinary disputes and preserve general standards for the Cosa Nostra. But the Mafia, like other crime syndicates, really had no peaceful means to resolve severe conflicts among its top leaders. They could not call the police or bring a civil action in court. Rather, they took matters into their own hands. Take the case of Anastasia's underboss Frank Scalise.

THE UP-AND-DOWN LIFE OF FRANK “CHEECH” SCALISE

After a lifetime in the mob, Frank “Cheech” Scalise had reason to be cynical.

He had once been a boss. Back in 1930, Scalise was one of the first to answer Salvatore Maranzano's calls for a revolt against Joe Masseria. As reward, Maranzano offered Scalise the opportunity to become a boss on “the condition that he would eliminate [Vincent] Mangano at the first opportunity.” Scalise took the deal to become boss.31

Then, Scalise delayed the hit. Growing impatient, Maranzano demanded to know why Mangano was still alive. Scalise tried to explain that he was unable to develop “any pretext to kill [Mangano] in order to justify his action with his countrymen.” The boss of bosses was extremely unhappy with Scalise.32

Fearing that Maranzano would send killers after him, Scalise spilled the beans about the murder scheme to Mangano's allies. This further fueled the conspiracy against Maranzano. As we saw, Charles Luciano's hit men killed Salvatore Maranzano in his Park Avenue office on September 10, 1931. Although Scalise probably saved his own life by revealing the scheme, he was not going to be a boss anymore. “Scalise's star fell. Scalise had been too close a supporter of Maranzano,” explained Bonanno. Scalise was demoted from boss and replaced by Vince Mangano. Scalise had gone from boss to has-been in a few months.33

Frank Scalise as Underboss: Franchising the Mob

It took twenty years for Scalise to claw his way back. Ironically, he returned over the dead body of Vince Mangano. Albert Anastasia made Scalise his new underboss in 1951. The mob's rackets were booming at the time. Crooks all over New York wanted in on the Cosa Nostra.

By 1956, Scalise decided it was his turn to cash in on his position as underboss. “Frank Scalise was accused, which was true, of commercializing this Cosa Nostra,” Joe Valachi explained. Scalise used his authority as underboss to sell memberships in the Mafia for cash payments. “It was rumored amongst us boys that he received about 40,000” dollars from each payee to become a soldier, recounted Valachi. Selling mob memberships was resented by the existing wiseguys. “We were all stunned when the word got out,” said Valachi. “In the old days a man had to prove himself to get it.”34

Scalise's actions offended not only their pride, but also their power and money. Albert Anastasia reportedly felt threatened by all the new men that Scalise was turning into soldiers. All these newly minted soldiers were beholden to Scalise. They might someday be used in a revolt against Anastasia.35 In addition, Scalise's rapid sale of mob memberships probably reduced the value of existing mob memberships. Although the soldiers would never put it in raw economic terms, as we saw earlier, much like a guild system or a franchise, “made men” could make more money by excluding others from the rackets.36 Lots of wiseguys wanted Scalise to be stopped.

Monday Afternoon, June 17, 1957, Produce Store, Arthur Avenue, The Bronx: Punishing Frank Scalise

Frank Scalise was always drawn to the Belmont/Arthur Avenue neighborhood, the Little Italy of the central Bronx. Unlike the Cosa Nostra, the residents there lived up to their Italian customs. Frank's brother Jack Scalise still ran a candy store in the neighborhood. Even after Frank moved out to City Island, on the water, he drove to the Italian shops along Arthur Avenue.37

On Monday afternoon, June 17, 1957, Frank Scalise was grocery shopping at a produce store on Arthur Avenue. He bought some fresh peaches and lettuce for ninety cents. As Scalise was stuffing the change back into his pocket, a pair of men brushed past the grocery proprietor. Before anyone knew what was happening, the gunmen took aim at Scalise and fired shots into his cheek, the side of his neck, and his larynx. He fell down dead atop his scattered change. The gunmen ran to a black sedan out front. A couple weeks later, Frank Scalise's other brother Joseph went missing and was presumed dead.38

Unlike after the attempt on Costello, Albert Anastasia did not bother going to the Commission to avenge the shooting of his underboss Scalise. After all, Anastasia had personally approved it. Carlo Gambino, a low-profile caporegime originally from Palermo, Sicily, was promptly named as his underboss. Despite the elimination of the despised Scalise, tensions were still growing in the Anastasia Family.39

THE LIFE OF A MOB BOSS: ANASTASIA'S DUAL FAMILIES

The NYPD's files on Albert Anastasia are stored at the New York Municipal Archives in Manhattan. Barely touched fifty years later, the files paint a rich portrait of Anastasia's life in the mid-1950s. What comes across in the files is how Anastasia compartmentalized his life. There was the Anastasia family of the New Jersey suburbs. Then there was the Anastasia Family of the New York underworld. Though he tried to keep his dual lives separate, they were never that far apart.

After the Second World War, Anastasia moved his wife and children to suburban Fort Lee, New Jersey. Anastasia bought a spacious Spanish-style house for $75,000 (about $650,000 in 2013 dollars) on the bluffs overlooking the Hudson River. It was surrounded by a steel perimeter fence and guarded by a pair of Doberman Pinschers. Fort Lee was a well-heeled New Jersey suburb with something of a mob enclave. Around the block was his mobster friend Joe Adonis. Anastasia soldiers Ernesto Barese, Paul Bonadio, and Sebastiano Bellanca had also moved to the neighborhood.40

9–3: House of Albert Anastasia on the bluffs overlooking the Hudson River in Fort Lee, New Jersey, 1957. (Photo from the New York Daily News Archive, used by permission of Getty Images)

Given Anastasia's obscene violence, it is often forgotten that he had a home life. He carried pictures of his wife and children in his wallet, and he phoned them whenever he was coming home late. On May 12, 1957, only ten days after the attempt on Costello, Anastasia went ahead with a christening ceremony of his new baby girl at the Essex House Hotel off Central Park, just a few blocks from the site of the Costello shooting. Albert had his brother Father Salvatore Anastasio perform the christening before hundreds of guests. That fall, his son Albert Anastasio Jr. entered his first year of law school at New York Law School.41

When asked about his work, Albert Sr., as well as members of his family, would point to his garment factory. “He is in the dress business in Pa.,” his son would say. Anastasia indeed owned a garment factory 130 miles away in Hazelton, Pennsylvania. It was a nonunion factory in the heart of coal country in the Wyoming Valley, a region rife with mob influence. The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union struggled to organize the workers in the face of a depressed economy and intimidation by mafiosi like Russell Bufalino and Tommy Lucchese. Anastasia let his underlings run his factory and keep out the union organizers.42

Anastasia spent most of his days across the Hudson River in New York City. What he did in the city was often a mystery to his family. As his son later said, his father “was not the type of man that was asked about his personal business.”43

ANASTASIA'S GAMBLING PROBLEM

In 1957, Anastasia was spending a lot of his time in New York wagering on sports. Anastasia had a gambling problem.

“Albert was losing heavy at the track, he was there every day, and he was abusing people worse than ever on account of that,” Joe Valachi recalled.44 Police investigators later discovered that Anastasia had fallen four months behind on the mortgage payments on his house in 1957. This despite the fact Anastasia was carrying around ample cash from his income from his garment factory and underworld sources.45

Anastasia's gambling was enabled by his sidekick Anthony “Cappy” Coppola. They met when Coppola was making a delivery for his family's business and hit it off immediately. Although the press dubbed Anthony Coppola his “bodyguard,” that is an overstatement. Coppola was Anastasia's driver and errand boy, personal bookie, and goodtime pal. Mostly, Albert and Cappy bet on the ponies during the day and spent nights out in Manhattan. “Cappie is a clown and a bookie,” described an ex-boxer who knew them from the racetrack.46 Another mafiosi deep into gambling recalled how Anastasia and Cappy were always asking for his opinions on sports bets. Whenever the telegraphed results of sporting events came in, they would be promptly relayed to Cappy's hotel room. “Invariably, [Albert] was in the room,” the mafiosi remembered.47

ANASTASIA'S ENCROACHMENTS

Anastasia's steep gambling losses may have had bigger consequences for the mob. Although Anastasia had always been an avaricious boss, he began acting more aggressively in his dealings with the other New York families.

According to multiple sources, Albert Anastasia began encroaching on the interests of others in 1956 and 1957. For example, Anastasia tried speaking to Vito Genovese and even Frank Costello about some internal matters in their mob syndicate. “We will take care of our family, you take care of yours,” he was told brusquely.48

Anastasia was eyeing the casino business in Cuba, too. This was the territory of Tampa Bay boss Santo Trafficante and his gaming partner Joe Silesi. One night over dinner with Joe Silesi in New York, Anastasia brought up Trafficante's bid for gambling concessions at the new Havana Hilton in Cuba. “I understand you’[ve] got a chance to get the Hilton casino,” asked Anastasia, who wanted a piece of the action. This surprised Silesi. Although he knew others were interested in the Havana Hilton, Silesi never guessed that the New York boss was among them. Anastasia later brought this up directly with Trafficante. “I hear you've got an application in for the Hilton,” Anastasia pried. “It looks like a big thing.”49

Meanwhile, the soldiers were still unhappy that Anastasia had let Scalise bring in so many new members into their ranks. There were rumors that Anastasia had taken a cut of Scalise's fee for new members. Anastasia was increasingly abusive to some of his own men, too. “Albert Anastasia was doing so much wrong and it was up to his family to act,” said Joe Valachi, recalling the view of the wiseguys.50

News of Anastasia's overreaching spread through the Mafia. In New England, members of the Patriarca Family began worrying that their old ally Anastasia might turn on them. Vinnie Teresa of Boston recalls that they “were afraid he wanted to take over the whole mob, become the boss of bosses.” An FBI informant close to the mob in Cuba said that “the very size of his organization posed a control threat to the Mafia itself,” which feared “an eventual bitter struggle for power” if Anastasia's family kept expanding. Another source based in Los Angeles said the Commission felt Anastasia “was too power-hungry and would be picking off the ‘Bosses’ one by one.”51

If this sounds vaguely familiar, recall how the plots began against Joe Masseria and Salvatore Maranzano. The rebellion of 1928–1931 started as reactions against the boss of bosses abusing his power and interfering with other Mafia families.52 In 1956–57, Anastasia was starting to act like a boss of bosses. Toppling overly powerful bosses seems to have been a natural response of the wiseguys.

A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A MOB BOSS: MONDAY, OCTOBER 21–THURSDAY, OCTOBER 24, 1957

Anastasia regularly kept suites at the luxurious Warwick Hotel and the San Carlos Hotel in Manhattan for himself and his pals and business associates. So when Tampa Bay boss Santo Trafficante flew into town the week of October 21, 1957, Anastasia reserved a suite at the Warwick. Although we do not know if they reached any agreements, Anastasia and Trafficante used the rooms to hash over the casino business in Cuba.53

On Thursday, October 24, Coppola spent the afternoon gambling in a room at the Warwick with Anastasia and Anthony “Little Augie Pisano” Carfano. They poured over horse scratch sheets, placed bets, smoked cigarettes, and waited for news of the winners. It was a rainy Thursday night in New York. Anastasia and Carfano wanted to eat out at a restaurant anyway. Coppola begged off, saying he was tired. After finishing dinner, Anastasia took Coppola's car and drove himself home that night to Fort Lee, New Jersey.54

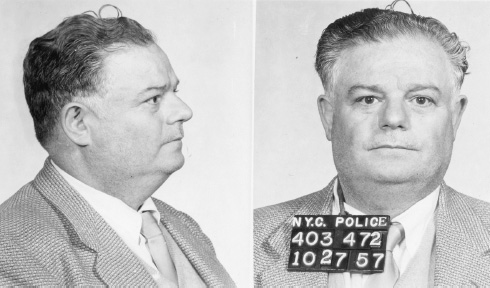

9–4: Anthony “Cappy” Coppola was Anastasia's bookie and goodtime pal in 1957. (Used by permission of the NYC Municipal Archives)

FRIDAY MORNING, OCTOBER 25, 1957, FORT LEE, NEW JERSEY, AND MIDTOWN MANHATTAN

Albert Anastasia woke up in his own bed on Friday morning, October 25, 1957. He saw off his son Albert Jr., the law student, on his way out the door at 7:30 a.m. The mob boss got dressed in a brown suit, white shirt, and tie. He was going to meet up with his caporegime Vincent Squillante, and get a haircut at Arthur Grasso's barbershop at the Park Sheraton.55

At about that same time, Santo Trafficante was checking out hurriedly from the Warwick Hotel. He had an early morning flight. Trafficante would be in Florida by the afternoon.56

Before he left his house in Fort Lee, Anastasia made a phone call to Coppola in his room at the San Carlos Hotel, instructing him to place some bets. “He wanted to place some doubles,” Coppola recalled. Cappy was supposed to meet up with Albert about 11:30 a.m., on the way to place bets at the race track. Anastasia stuffed $1,900 in cash into his pockets (about $15,000 in 2013 dollars), got into Coppola's borrowed car, and drove himself to Manhattan.57

At 9:28 a.m., Anastasia pulled into a rental garage on West 54th Street. It was a brisk fall morning in Manhattan. Anastasia met up with Vincent Squillante, and they walked over to the Park Sheraton Hotel on the corner of West 56th Street and 7th Avenue.58

On the ground floor of the Park Sheraton that same morning was boxing manager Andrew Alberti and his fighter Johnny Busso, who had a room at the hotel. At about 9:15 a.m., they went downstairs to the hotel restaurant for breakfast and mingled in the lobby. Alberti was not supposed to be managing boxers. The New York Athletic Commission had officially banned him from boxing because of his ties with mobsters. Andy Alberti was especially close to Steve Armone and Joseph Biondo of the Anastasia Family.59

10:15 A.M., OCTOBER 25, 1957, BARBERSHOP OF THE PARK SHERATON HOTEL, MANHATTAN

Albert Anastasia's favorite place for a haircut was Arthur Grasso's barbershop at the Park Sheraton. The proprietor ran an old-style barbershop with mirrored walls, chrome-and-baby-blue barber chairs, shoe shines, and skilled Italian barbers. Anastasia went there twice a month for a trim.60

At 10:15 a.m., Anastasia and Squillante walked into the barbershop and hung up their jackets. “Haircut,” Anastasia nodded. The barber escorted Anastasia over to barber chair number four with a corner window. Squillante eased into another chair for a shave.61

The proprietor Arthur Grasso came over to greet Mr. Anastasia. As the barber spread the cloth over Anastasia's white shirt, and the shoeshine polished his brown shoes, Grasso pulled up a stool to catch up with his friend. At about 10:20 a.m., Grasso got up from his stool to check the soap machine. Anastasia let his head hang limply forward so that the barber could clip behind his neck. He was completely relaxed….62

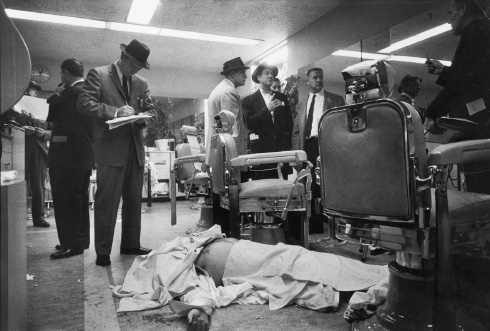

Two men in hats and aviator glasses slipped across the threshold of the barbershop, black gun barrels poking out from their coats. The lead gunman walked briskly up to the rear right side of Anastasia's chair and fired away—BANG BANG BANG! “They went off fast; sounded like firecrackers,” recalled Grasso. Anastasia bolted out of his chair in pain, breaking the chair's foot rest as he lunged toward the mirrors. Rushing up to the left side of the chair, the second gunman emptied his revolver at the wobbling mob boss—BANG BANG BANG BANG! But it was the lead gunman who fired the fatal round: a .38-caliber bullet struck the back of Anastasia's head and lodged in the left side of his brain. Anastasia collapsed between his barber chair and the next chair to the right.63

9–5: Police photo of Anastasia Family associate Andrew Alberti, 1957. (Used by permission of the NYC Municipal Archives)

The assassins made their escape. They tried exiting through the side door, but the door was locked. The lead gunman turned around and backtracked through the main doors. “Nobody move,” warned the second gunman to the barbers crouching down in fear.64 The lead gunman dumped his .38-caliber Colt revolver in the glass vestibule of the hotel before exiting onto the sidewalk of West 55th Street. They scurried down the steps of the nearby subway station and escaped on a departing train. A city worker later found the second gunman's .32-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver in a waste box in the station.65

Back at the barbershop, the employees were in shock. The proprietor Arthur Grasso had literally crawled out of the shop to a ticket office next door. The only person with the presence of mind to try to help Anastasia was a physician who happened to be getting a haircut. Anastasia's upper torso was twisted over, his white shirt splattered in blood, and his face pressed onto the cold floor. The doctor checked for a pulse. Anastasia was gone.66

THE NYPD INVESTIGATION

Police responded to the scene within minutes. Flocks of newspaper reporters descended on the barbershop to cover the daytime murder of a mobster. Anthony “Tough Tony” Anastasio was notified about his brother while at his office at the International Longshoremen's Association in Brooklyn. He sped over to Manhattan. After seeing his brother on the floor, Tony left the barbershop weeping in despair.67

Although the police tried to get clear descriptions of the gunmen, some of the eyewitnesses may have been intimidated by this gangland shooting. The NYPD later conducted polygraph examinations of the barbershop employees. The polygraph examiner found “deception” in the answers of three barbers regarding whether they could positively identify the shooters. The examiner concluded that the barber who was shaving Squillante in chair number four had lied about being unable to identify the shooters because he was in “fear for self & family,” and did not “care who knows he is lying.”68 The police never found evidence that any of them were involved. They were simply too scared to talk.

9–6: Body of Albert Anastasia in hotel barbershop, October 25, 1957. (Photo by George Silk, used by permission of Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

Meanwhile, Anastasia's caporegime Vincent Squillante was nowhere to be found. During the shooting, Squillante had run out of the barbershop with lather dripping off his face. He subsequently refused to cooperate with the NYPD's investigation. According to the NYPD report of his 1958 interrogation, Squillante flatly “refused to answer any questions on the grounds that he might incriminate himself.”69

The police nevertheless put together descriptions of the shooters from the barbershop employees willing to talk. At 4:44 p.m. that afternoon, the NYPD sent out a Teletype message: “HOMICIDE OF ALBERT ANASTASIA, OCT 25, 1957.” The lead gunman was described as a white male around forty years old, 5’8” and 180 pounds, with “sallow complexion.” He was dressed in a grey suit and fedora hat. The second gunman was described as a white male about thirty years old, 5’5” and 150 pounds, with “light complexion” and a “thin black pencil mustache.” He was dressed in a brown suit and hat, and had on dark green aviator glasses. Both suspects spoke American English with no foreign accent.70

THE MOBSTERS BEHIND THE PLOT

There is virtual unanimity in the underworld about who was behind the plot to kill Anastasia. “I believe that Vito Genovese worked hand in hand with [Carlo] Gambino and [Gambino deputy] Joe [Biondo],” said Joe Valachi in his 1963 testimony before Congress. Genovese went so far as to warn Valachi to “stay away from Albert's men.”71 Vincent “Fat Vinnie” Teresa stated that Vito Genovese was the “mastermind of the conspiracy,” and Carlo Gambino was the “inside man” in the plot.72 New York boss Joe Bonanno said that “the indications were that it was men within [Anastasia's] own Family.”73

Vito Genovese and Carlo Gambino had strong motives to kill Anastasia. As long as Anastasia was alive, Genovese had to worry that the volatile Albert would come after him. Eliminating Anastasia would also end any of Frank Costello's lingering notions about returning as boss. For the quietly ambitious Gambino, as the underboss of the Anastasia Family, he would be the logical successor to become the next boss once Albert was gone.74

For a long time, the NYPD focused on Santo Trafficante as a suspect in the plot.75 Trafficante was, after all, meeting with Anastasia in the days leading up to his murder. The Florida boss may have had second thoughts about letting Anastasia get a foothold in Havana. In November 1959, two years after the shooting, the NYPD was requesting that the Tampa Bay police put surveillance on Trafficante. But without the FBI's involvement, the NYPD was never able to question Trafficante in Florida or Cuba. So the investigation of him fizzled.76

THE SUSPECTED SHOOTERS

In contrast to the plotters, the identities of the shooters are still the subject of debate. This section lays out the evidence for the top suspects.

Profaci Family soldier Joseph “Crazy Joe” Gallo told people that he and his brother's crew were the shooters. In a 1963 article for the Saturday Evening Post, a gambler named Sidney Slater said that Joey Gallo had once boasted to him in a bar, “You can just call the five of us the barbershop quintet.”77 In his 1976 tell-all book, Peter “The Greek” Diapoulos, an associate of the Gallo crew, claimed that Vito Genovese and Joseph Profaci “gave that piece of work to our crew, designating Larry and Joey Gallo and Joe Jelly [Joseph Gioielli].”78

There are strong reasons to doubt that the Gallo brothers were the actual shooters. The Gallo crew was part of the Profaci Family. The Gallos had no connections to either Vito Genovese or Carlo Gambino. Moreover, the man they called “Crazy Joe” Gallo was known as an unreliable braggart. In his 1963 article, Sidney Slater acknowledged: “It's even possible Joey was boasting, having his kind of fun.”79 The Gallo brothers were not the type of men that the Profaci Family would lend out to another mob family to execute a high-level assassination. There are more compelling suspects.

In 2001, veteran mob journalist Jerry Capeci first reported that the Anastasia assassination was carried out by a crew selected by Gambino caporegime Joseph Biondo.80 According to Capeci's report, the crew leader was Stephen Armone. He reported that the “primary shooter” was Stephen “Stevie Coogan” Grammauta, a then-forty-year-old heroin trafficker, and that the “second shooter” was Arnold “Witty” Wittenberg, a then-fifty-three-year-old Jewish drug dealer. Capeci cited unidentified “knowledgeable sources on both sides of the law” as the basis for his report. Given Capeci's proven track record and deep sources in the mob and law enforcement, his report must be taken seriously.81

Documentary evidence has since been discovered that corroborates the story that Steve Grammauta was the lead gunman, and that he was acting under the direction of Joseph Biondo. The documents are stored separately in the FBI records in the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, and in the NYPD's files on the Anastasia case in the New York Municipal Archives. There is no indication that the FBI and the NYPD shared these documents at the time.

In an FBI report dated January 3, 1963, a confidential Mafia informant told the FBI that Joseph Biondo and Andrew Alberti helped organize the crew, and that the contract was given to “Steve Grammatula [sic]” whose “nickname is Steve Coogan.” The informant explained that since “Anastasia frequented the barbershop at the Park Sheraton Hotel,” the crew arranged so that “the guns were in the hotel room of Johnny Busso /PH/, a fighter.” (The informant did not assert that Busso knew of the assassination plot, and there is no evidence that Busso was in any way involved). The informant stated that “Grammatula [sic] went to the hotel, got the guns, shot Anastasia, and caught [the] subway and went home.”82 The informant's account is all the more credible because Grammauta was never publicly identified as a suspect, and Alberti's and Busso's presence that morning at the Park Sheraton Hotel was not reported by the newspapers. The informant was therefore not simply repeating what he had read in the papers.83

The NYPD's internal files on the Anastasia investigation confirm that Andrew Alberti and Johnny Busso had a room at the Park Sheraton hotel, and they were in the lobby that morning. According to the NYPD's report on its interrogation of Busso, the boxer recalled how “on the morning of October 25, 1957, he received a phone call in his room from Andrew Alberti,” who then “came up to his room.” They went down for breakfast in the hotel restaurant at “about 9 or 9:15 AM.” Busso said that he “spoke with numerous persons in the lobby of the hotel that morning in question, but does not remember Alberti introducing him to [Anastasia].”84 For his part, Andy Alberti admitted that he ran into Anastasia that morning in the Park Sheraton lobby, and that they had a conversation during which Anastasia “spoke…about Busso's coming fight at the Garden.” Although Alberti claimed he had no information on the murder, he also told the police that “he would not give any information, even if he possessed it, pertaining to this or any other crime.” The police knew they were dealing with a mobster: the report on Alberti notes that his associates “include Joseph and Stephen Armone.”85 In November 1964, Alberti would be killed by a shotgun blast in what the police believed was a gangland murder.86

Steve Grammauta's background and appearance made him a logical suspect as the lead gunman. Grammauta was a low-profile mafioso with close ties to the Armone brothers of the future Gambino Family. He would be convicted with Joseph Armone (the brother of Stephen Armone) for running a heroin ring that they operated between 1956 and 1960. Furthermore, Grammauta fits the description of the first gunman, a “white male around forty-years-old” (Grammauta was forty in October 1957) with a “sallow complexion” (the man nicknamed “Stevie Coogan” had pale skin).87

Based on these sources, we can broadly outline the assassination plot. By the fall of 1957, the grievances against Albert Anastasia have reached a boiling point. Carlo Gambino's trusted lieutenant Joseph Biondo secretly assembles a team to eliminate the boss. Biondo selects his close associate Steve Armone to lead a crew of gunmen. They know that Anastasia gets his hair cut twice a month at the barbershop on the ground floor of the Park Sheraton hotel. So they stash revolvers in the room of one of Andy Alberti's fighters, who stay at the hotel before fights. They confirm that the boss is getting his regular trim on the morning of Friday, October 25, 1957. Steve Grammauta and the second gunman get the revolvers from the hotel room, put on their hats and aviator glasses, and head downstairs. At about 10:20 a.m., they slip across the threshold of the barbershop….88

THE AFTERMATH

“ANASTASIA SLAIN IN A HOTEL HERE,” read the New York Times.89 The murder of Albert Anastasia shook up the underworld. There had not been a public assassination of a New York Mafia boss since the murder of Salvatore Maranzano in September 1931. (Vince Mangano's killing in 1951 was carried out in secret).90

Carlo Gambino and his lieutenants moved swiftly to claim the mantle of leadership. As Joe Bonanno discovered, after Anastasia was killed, the plot's “second phase involved the quick recognition of Carlo Gambino as Anastasia's successor.”91 With the backing of Vito Genovese and Tommy Lucchese, Gambino became the boss of the new Gambino Family. Gambino named Joe Biondo as his underboss as reward for his ruthless service.92

The murder and replacement of Anastasia took place without major opposition. By October 1957, few wiseguys had any desire to avenge Anastasia.93 The ferocity of “The Executioner” shocked even other mobsters, who wondered when they might be his next victim. The murders of Vincent and Philip Mangano, the dumping of Peter Panto in a lime pit, the unpredictable outbursts of rage—it was too much even for his closest associates. “I ate from the same table as Albert and came from the same womb, but I know he killed many men and he deserved to die,” said his brother Anthony Anastasio to FBI agents in a confidential conversation.94

With all the upheaval in New York, the Commission called a national meeting in 1957. The main purposes of the meeting would be to affirm Vito Genovese's accession as boss of the new Genovese Family and to introduce “Gambino to the important men in our world.”95 Don Vito wanted to hold the meeting in Chicago. But Stefano Magaddino of Buffalo persuaded the Commission to hold it at his friend Joseph Barbara's fifty-eight-acre estate in upstate New York. Barbara's place was located outside the factory town of Endicott in a village called Apalachin.96