Then I would have been sorry for the dear Lord. The theory is correct.

Albert Einstein, 1919

ON 14 JUNE 1360 a cycle of 71 solar eclipses, now known as saros series 136, began when the Moon’s penumbra barely touched the southern polar region. Modern computations of the paths of the other 70 eclipse tracks across the globe tell us that the last in this series will just graze the north polar region on 30 July 2622. Near the midpoint of this 1,262-year cycle, on 29 May 1919, the 32nd eclipse in the series cast its shadow across the tropics.

On that day the Moon’s shadow touched the Earth just west of South America and moved across Peru, Bolivia and Brazil to the Atlantic Ocean. Continuing its journey over the southern part of Africa, the shadow finally disappeared at sunset in the Indian Ocean. Just before reaching the west coast of Africa, the shadow had traversed the small island of Principe. Waiting there, with a powerful telescope and a large-format camera, was the English astronomer Arthur Eddington, ready to photograph the stars behind the eclipsed Sun. Several thousand kilometres away in his Berlin study, the German physicist Albert Einstein patiently awaited the results.

It is hard to imagine two scientists more different than Eddington and Einstein. Yet they were destined to collaborate in solving one of the greatest puzzles of the universe.

Einstein (1879–1955) was the son of a Swiss German businessman who worked hard to provide the best possible education for his offspring. But Albert loathed Switzerland’s rigid system of schooling. He attended a Catholic elementary school and then a Gymnasium (high school). He was no model pupil, arguing with his teachers and showing little respect for them or their teaching. He completed his undergraduate degree at the Technische Hochschule (Technical High School) in Zurich, helped through his examination by his well-organised friend Marcel Grossman. Einstein day-dreamed and read the latest publications in physics journals while Grossman took careful notes. Einstein said of this period that cramming for his examinations had such a deterring effect on him that for an entire year afterwards he found it distasteful to consider any scientific problem. The year after receiving his degree, he applied everywhere for a job. As a problem student, the young and disappointed scientist found he could not obtain an academic position.

Finally, on 23 June 1902, Einstein started work at the Swiss Patent Office in Berne as probationary Technical Expert, Third Class, on the modest salary of 3,500 francs per year. He quickly became adept at the work, and was happy to be free of the hostile academic world that had brought him repeated heartache. In his spare time he could work quietly and with growing excitement on developing his revolutionary ideas. In this unlikely conservatory, his genius matured.

In 1905, at the age of twenty-six, Einstein was already contributing papers to scientific journals. That year he had four papers published in the Annalen der Physik, the prestigious German physics journal. The third paper, the most interesting to Einstein, was entitled ‘On the electrodynamics of moving bodies’, a subject that has since become known as the special theory of relativity. In this paper Einstein solved most of the problems that still remained in classical physics, but to do so he had to change for ever the way we think of time and space. He drastically modified the underlying assumptions of the Newtonian universe.

Einstein had his own way of investigating the puzzles he found in the physical universe. He would ask himself ‘What if …’ type questions. The hypothetical situations he imagined could never be realised in practice but were consistent with the laws of physics. He called these gedanken or ‘thought’ experiments, carried out in a kind of laboratory of the mind. For the special theory of relativity of 1905, he asked how two different observers would experience or record a sudden bolt of lightning in the sky. One observer he imagined to be in a moving train, while the second observer was at rest on a platform as the moving train passed by.

Part of the Sun is drawn to scale on the inside front cover of this hook. The separation between the Moon and Earth would be 54.6 mm. The Earth and the Moon and their separation are shown to scale. The Earth’s diameter is 1.83 mm to scale, and the Moon’s diameter is 0.5 mm. Why page? Because we need nearly the entire extent of this book, from the inside front cover to page, to represent on this scale the distance from the Sun to the Earth. This is with all the pages opened out like an accordion, double-sided. At this distance the image of the Sun viewed from the Earth shrinks to 0.5 mm, and is just small enough to be obstructed by the image of the Moon, which is also 0.5 mm across on this scale.

Applying strict logic and consistency in this thought experiment, Einstein insisted that there should be symmetry in the laws of physics for both observers. He believed that with uniform motion it should not matter which observer is considered to be at rest and which is considered to be moving. The laws of physics as experienced by the two observers had to be equivalent. For example, it makes no difference if the observer on the platform is imagined to be moving towards a stationary train, rather than the observer in the moving train moving towards the observer on the platform: the results of any measurement should be the same. Einstein’s only postulate was that the speed of light was a constant, that both observers would measure light to be travelling at the same speed, regardless of which of them is considered to be moving and which is at rest.

Einstein found that if he accepted these arguments he would have to abandon the concept of absolute time, thought of as a clock ticking away somewhere at the centre of the universe. He would also have to dispose of the concept of absolute space, a grid of fixed coordinates spread out through the universe. He concluded that his two observers would see each other’s clocks ticking at different rates, and find each other’s measuring rules to be of different lengths. A characteristic time for each of the two observers, the moving and the stationary, needed to be added to the usual three space dimensions to completely specify the condition (the ‘state’) of a system. This became known as the fourth dimension. These ideas opened up a fissure in the framework of Newtonian physics which could be repaired only by redefining the nature of space and time.

Arthur Eddington (1882–1944), born into a devout Quaker family at Kendal in the foothills of England’s beautiful Lake District, was three years younger than Einstein. As a dutiful son of a successful schoolmaster, he was a model student, almost the antithesis of his German colleague. Yet he had the same obsessive fascination with the physical universe. With determination and careful guidance through all the hoop-jumping of the English educational system, Eddington made it to Cambridge at the age of twenty, entering Trinity College in the autumn of 1902. He finished the three-year Tripos course in mathematics and physics at Cambridge in just two years, and when the results were declared his name headed the list. Never before had a second-year man won such a distinction.

After lecturing for a year at Cambridge, Eddington was offered the post of Chief Assistant at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, and his career as an astronomer began. He immediately contributed important work on contemporary problems in astronomy, particularly on the motion of stars and the structure of the universe. In 1914 he returned to Cambridge as Plumian Professor of Astronomy. By this time Eddington knew of Einstein’s published work on special relativity, but was not aware of the German’s struggle to generalise the conclusions of the 1905 paper to non-uniform motion.

Einstein had what one might call artistic objections to his own theory of special relativity. In this theory he had considered a train moving uniformly past a stationary observer. From this he was able to show that there is no difference between the observer in the moving train and the observer on the platform in terms of the measured observations. Now he asked what would happen if the train was accelerating. Why should uniform motion be special? How much more satisfying it would be if all motion, uniform or not, were relative. The laws of physics would then be the same in any frame of reference.

But the facts were clearly against him. The observer in an accelerating train will not experience his surroundings in the same way as a stationary observer. We all know this, and do not need to study Newton to be convinced of it. In a smoothly moving train we feel no sense of motion other than the vibration of the carriage. But if the train accelerates, it causes a lurch which we feel at once.

To bring gravity into the picture, imagine, instead of the train, a lift going to the top of a tall building. In a lift moving at uniform speed we detect no evidence of motion other than the vibration of the lifting gear. But at the start and finish of the journey we feel an odd sensation in the stomach caused by the acceleration and deceleration of the lift. Einstein decided to try another gedanken experiment to examine accelerated motion, when the speed is changing. This led to another kind of equivalence.

Figure 7.1. The principle of equivalence I: The acceleration A is equivalent to the gravitational pull G for a passenger in a windowless lift.

Imagine a passenger lift set adrift in space far from other gravitational bodies. Its occupants would feel no ‘weight’. An apple ‘dropped’ by someone in the lift would not fall to the floor but would remain suspended at the point where it was released. This weightlessness is familiar from images of astronauts in a free-falling space capsule in orbit around the Earth. Now, imagine accelerating the lift in a direction that the occupants would call ‘up’ at a rate that increases its speed by 9.8 metres per second in each second. This is the magnitude of the acceleration caused by gravity as measured at the surface of the Earth. The floor will accelerate up and hit the apple.

We may ask at this point, ‘The lift is accelerated relative to what?’ Einstein stated in the special theory that it is not possible to measure the absolute speed of a single object, only its speed relative to something else. Although the speed cannot be detected, its acceleration or the increase of the speed, 9.8 metres per second every second, can be. For example, it gives the occupants of the lift the sensation of ‘weight’, for they are pushed to the floor. This change can be felt in the same way as the lurch in the accelerated train.

Now, if a planet exactly like the Earth is moved past the same lift with its occupants, they experience exactly the same sensation as they did in the upwardly accelerating lift in outer space. They feel weight, and the apple hits the floor. The passengers might wish to distinguish the upwardly accelerating lift from the pull of the moving planet, but they cannot. If there are no windows in the lift, there is no experiment they can do by which they can tell one effect from the other, the acceleration up or the gravitational pull down.

Einstein said simply that the two effects are equivalent, and that differences in a body’s reaction to acceleration, called inertia, and its reaction to gravity, called gravitation, are artificial. He announced his principal of equivalence in 1911 and immediately applied it to a variety of problems. He already knew how to calculate the effect of acceleration on various phenomena, even when gravitation would not have been expected to produce any effect. Now he could replace gravitation by acceleration and look for the effects.

Figure 7.2. The principle of equivalence II: A light beam bends in the gravitational field G of the planet which is equivalent to acceleration A.

The first problem to which he applied his new principle was determining the path of a beam of light. To examine this we need to return to the lift in outer space. If a laser beam is fired from one side of the lift to the other when the lift is in uniform motion, the path of the laser beam will be a straight line. This is because the laser is moving at the same speed as the lift. To an observer inside the lift, it will hit the opposite side at the height from which it was fired.

However, a laser beam fired from one side to the other in a lift which is accelerating upwards will appear to an observer in the lift to follow a curved path, and to strike the opposite side below the height from which the laser was fired. Since the principle of equivalence states that the effects of acceleration and gravitation are the same, a gravitational field must also cause a light beam to bend. This was new and unexpected. Einstein had found a new equivalence for accelerated motion.

Einstein, who is usually thought of as a completely theoretical creature of mathematics and geometry, suggested shortly after announcing the principle of equivalence that an experiment carried out during a total eclipse of the Sun would test the idea of the gravitational deflection of light. ‘As the fixed stars in the parts of the sky near the Sun are visible during total eclipses of the Sun, the consequence of the theory may be compared with experiment,’ he stated.

The principle of equivalence was a key part but nevertheless a small part of the elaborate theory of general relativity. With help from Marcel Grossman, who was expert in just the branch of mathematics which he needed, Einstein formulated a final set of equations which fulfilled his aesthetic criterion that the laws of physics will be the same for uniform or accelerated motion. He found that the concept of a force of gravity was no longer necessary. Newton’s gravitation was replaced by Einstein’s curved space.

Now confident that he had the correct equations, Einstein immediately applied them to the unusual orbital motion of the planet closest to the Sun, Mercury. Newton’s theory had been unable to explain the marked drift of the perihelion point of Mercury’s orbit around the Sun. All the planets perturb one another through their gravitational pulls. One effect of this is that their elliptical orbits are themselves rotating, so that a planet’s perihelion – the point at which it is closest to the Sun – moves a little further around the Sun at each orbit. In Mercury’s case, this advance of the perihelion was greater than could be explained by Newtonian gravitation. Einstein’s new theory predicted exactly the difference between the observed drift and the drift predicted from Newtonian theory. He showed that where gravity is weaker, for example at points in the Solar System farther from the Sun than Mercury’s orbit, the new theory reduced to the Newtonian formulation. This must be true, since Newton’s theory had been successfully confirmed by all calculations based on gravitation for over three hundred years, except in the case of the advance of Mercury’s perihelion.

Finally, Einstein calculated the angle through which a light beam would bend if it just grazed the edge of the Sun. The general relativity theory predicted a displacement of 1.75 seconds of arc. This was exactly twice the value calculated using Newton’s mechanics applied to light considered as a stream of particles. This may seem a very small angle (there are 3,600 seconds of arc in one degree), but it could be measured quite accurately with a good telescope. Einstein knew this and suggested that a precise photographic study of the eclipsed Sun could decide between his own theory of gravitation and that of Isaac Newton.

Einstein announced the final results in a fifty-page paper published in the Annalen der Physik in 1916, describing his new theory, which he called general relativity. As soon as the theory was announced, a colleague of Einstein’s, Erwin Freundlich of the Potsdam Observatory near Berlin, examined photographs of past eclipses, but they were inconclusive. Astronomers at the Lick Observatory in the USA tried to photograph the solar eclipse of 8 June 1918 but were defeated by cloudy skies. When the First World War ended with the armistice of November 1918, the idea was taken up by the British.

Einstein’s plan was simple and practical. First, the date of the next total solar eclipse to occur after the war had to be looked up. Then a large telescope and high-resolution camera had to be transported to a location on the path of totality and set up to photograph the eclipsed Sun. At the moment of second contact, when the Moon completely covers the Sun for the first time, stars would appear around the Sun in the darkened sky. Light from these stars, having travelled vast distances for tens, hundreds or even thousands of years, would pass near the outer rim of the eclipsed Sun, enter the camera and record images on the photographic plate. If Einstein was right, these beams would be bent by the curvature of space near the Sun caused by the Sun’s strong gravitational field, and would be deviated along a new path before reaching the camera on Earth. To detect the shift in the apparent position of the stars, it would be necessary to compare the photographs of the displaced positions with photographs of the same field of stars taken when the Sun was in a different position and the starlight would not be deviated.

Figure 7.3. Measurement of the bending of starlight during a solar eclipse. The observer on Earth (Eddington) sees the star at the edge of the eclipsed Sun. The star is actually behind the Sun.

It goes without saying that for this experiment to succeed, the sky had to be clear, the resolution of the camera had to be high enough to produce sharply focused star images on the photographic plates, and there had to be sufficiently bright stars visible in the vicinity of the eclipsed Sun. Clearly, there is not much that experimenters could do about the vagaries of the weather. But they could make certain that the camera was up to the task, and they could also select an eclipse that took place against a bright star field. This last requirement could be a problem because there are only on average two eclipses each year.

Given the rarity of a total solar eclipse and the scarcity of bright stars along the Sun’s annual path, astronomers might expect to wait years for a suitable opportunity. But this was not to be so. If astronomers had a free choice of the optimum star field behind the Sun for such an eclipse photo-experiment, they would probably choose the day of the year when the Sun, in its journey through the constellations of the zodiac, is positioned in the middle of the bright star cluster in Taurus called the Hyades. The Sun is in the Hyades on 29 May each year. Imagine the enthusiasm when it was realised that the next total solar eclipse, the first since the end of the war, would fall on 29 May 1919. Furthermore, this particular eclipse was to be 6 minutes and 50 seconds in duration, close to the theoretical maximum.

It is not surprising that while the war was still in progress, Sir Frank Dyson (1868–1939), the Astronomer Royal, had seized the opportunity for testing Einstein’s theory which this particularly favourable eclipse would afford. He obtained a Government grant of £1,000 and naturally turned to Eddington, a long-standing member of the Royal Observatory staff, for help with planning the expedition.

Eddington, as Secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society during the war years, had maintained a constant communication with cosmologist Willem de Sitter in neutral Holland. De Sitter had sent Eddington copies of all Einstein’s papers on the developing theory, even before they were published. Eddington had become translator and popular expositor of the difficult general relativity theory for English readers. He seemed destined to play an important role in the drama of the eclipse test.

It has generally been understood that, as the leading proponent of Einstein’s new theory and one of the world’s top astronomers, Eddington was the driving force behind the eclipse expedition. But this is not true. For one thing, he had no doubt that Einstein’s theory was correct, and did not feel that it was necessary to confirm the predictions with such a difficult experiment as photographing a solar eclipse. But he was drawn into the project by Dyson, and a rather fortuitous set of circumstances resulting from his pacifist beliefs.

For a properly planned eclipse expedition, preparations would have to begin about two years beforehand. Although Dyson did have his small grant, it was impossible to ask any instrument-maker for help when the war effort had first call on resources. And there were other complications as well. Eddington, an able-bodied thirty-four-year-old male, was subject to the call-up. But as a devout Quaker, it was well known that he would claim deferment as a conscientious objector and end up peeling potatoes in a camp in northern England with other pacifists.

The Cambridge big shots argued effectively with the authorities that it was not in the country’s best interests to have such a distinguished scientist as Eddington serve in the army. They no doubt used the sad case of the brilliant young crystallographer Henry Mosely, killed at Gallipoli, to convince them. Finally, Eddington received a letter of deferment from the Home Office. All he had to do was sign and return it. But the bloody-minded Eddington insisted on adding a postscript saying that if he was not deferred in the present instance, he would claim it anyway as a conscientious objector.

Much to the frustration of the Cambridge crowd, the Home Office reacted angrily to Eddington’s response, and prepared to pack him off with the other pacifists. But Dyson, as Astronomer Royal, intervened directly. In the end, Eddington was deferred with a stipulation that if the war should end before May 1919, he should undertake to lead an eclipse expedition to verify Einstein’s theory. Clearly, Dyson’s influence had been felt!

A joint committee of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society, headed by the Astronomer Royal, was set up to organise the project. They planned two separate expeditions: one to Sobral, Brazil and the other to the island of Principe off the coast of West Africa. As the war ended, Eddington admitted to Dyson that he had an intense spiritual feeling about the expedition. He chose to go to Principe and was given permission to take with him the high-quality lens of the Oxford astrographic telescope. He sailed in early March for Lisbon.

Eddington arrived on Principe in good time. For weeks he fussed with the telescope’s mounting, which apparently was acting erratically. He knew that the images of the displaced stars would have to be photographed very carefully during the eclipse. A high degree of accuracy would be necessary to differentiate between Einstein’s prediction of the displacement of starlight at the edge of the Sun of 1.75 seconds of arc and that based on Newton’s theory of half that value, 0.875 seconds of arc. He built a special observing hut and eliminated all possible sources of vibration in the support of the telescope. Finally, there was nothing to do but wait for the new Moon’s path to cross the Sun’s on the ecliptic.

From 10 May onwards rain fell every day. On the fateful 29th, as the moment for the eclipse approached, the Sun was completely obscured by clouds. The despairing Eddington, praying for a miracle, pointed his telescope at the Sun and removed the shield covering the photographic plate. As the eclipse began he removed the lens cap from the telescope and took several photographs of a dark cloudy sky. As the 400 seconds of totality ticked by, Eddington could see no stars in the view. Then, suddenly, the miracle. The clouds began to evaporate and a few stars became visible for just a moment. He quickly exposed a fresh plate before the Sun appeared again from behind the Moon’s shadow.

From his own notebook, Eddington’s personal account of the expedition reveals his frustration on the day of the eclipse:

We got our first sight of Principe in the morning of April 23 and soon found we were in clover, everyone anxious to give every help we needed. About May 16 we had no difficulty in getting the check photographs on three different nights. I had a good deal of work measuring these. On May 29 a tremendous rainstorm came on. The rain stopped about noon and about 1.30, when the partial phase was well advanced, we began to get a glimpse of the Sun. We had to carry out our programme of photographs in faith. I did not see the eclipse, being too busy changing plates, except for one glance to make sure it had begun and another half-way through to see how much cloud there was. We took 16 photographs. They are all good of the Sun, showing a very remarkable prominence; but the cloud has interfered with the star images. The last six photographs show a few images which I hope will give us what we need.

He developed the plates and found star images on only one of them. Eagerly, he made tentative micrometer measurements of the displacement of several stars. To his delight he found an average displacement angle of 1.61 seconds of arc. This value favoured Einstein’s new theory over Newton’s. As Eddington put it a few days later in his journal:

June 3. I developed the photographs, 2 each night for 6 nights after the eclipse, and I spent the whole day measuring. The cloudy weather upset my plans and I had to treat the measures in a different way from what I intended, consequently I have not been able to make any preliminary announcement of the result. But the one plate that I measured gave a result agreeing with Einstein.

Eddington never forgot that day, and on one occasion in later years he referred to it as the ‘greatest moment of his life’. Upon returning to England, the eclipse photographs were analysed very carefully before the results were communicated. By September rumours had reached Einstein that the eclipse results were favourable. Even though the war was now over, Eddington was still communicating via his colleague de Sitter in Holland. On 22 September Einstein received a telegram from his friend, the respected Dutch physicist Hendrik Lorentz, that Eddington had found the full deflection of the starlight in agreement with general relativity. The nearly unbelieving son immediately sent a postcard to his ailing mother in Switzerland: ‘Dear Mother, Good news today. H. A. Lorentz has wired me that the British expedition has actually proved the light deflection near the Sun.’ It would appear from this message that Einstein was slightly uncertain how the eclipse result would turn out. This may have been true. But he was never uncertain about the theory itself, as is clear by an incident from this period which would be recounted in the common rooms of physics and astronomy departments the world over.

A student of Einstein’s at the University of Berlin in 1919, Ilse Rosenthal-Schneider, told how one day when she was studying with him, he suddenly interrupted the discussion and reached for a telegram that was on the window sill. He handed it to her with the words, ‘Here, this will perhaps interest you.’ It was the cable from Eddington with the results of the eclipse measurements. After she expressed her joy that the results coincided with his calculations, he said, quite unmoved, ‘But I knew that the theory is correct.’ She then asked Einstein how he would have felt if there had been no confirmation of his prediction. He replied, ‘Then I would have been sorry for the dear Lord, because the theory is correct.’

Figure 7.4. The results of the British eclipse expedition, 29 May 1919. Note that the line drawn through experimental measurements is much closer to Einstein’s theory than to Newton’s. (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Vol. 220, 1919)

Einstein replied shortly afterwards to his English colleague, addressing him ‘Lieber Herr Eddington!’ The first paragraph of the letter reads (in translation):

Above all I should like to congratulate you on the success of your difficult expedition. Considering the great interest you have taken in the theory of relativity even in earlier days I think I can assume that we are indebted primarily to your initiative for the fact that these expeditions could take place. I am amazed at the interest which my English colleagues have taken in the theory in spite of its difficulty.

But the news was still unofficial. On 6 November 1919, a historic joint meeting of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society was held in London. In 1703, more than two centuries earlier, Newton had been elected President of the Royal Society, and annually thereafter he had been re-elected till his death. Now, in 1919, he was vividly present in the minds of the assembled scientists. His portrait, in its place of honour on the wall, dominated the scene. Yet though he faced the audience, it seemed as though his eyes were turned sharply to the right as the Astronomer Royal officially announced that ‘the results of the expedition can leave little doubt that a deflection of light takes place in the neighbourhood of the Sun and that it is of the amount demanded by Einstein’s general theory of relativity’.

At the conclusion of the meeting, J. J. Thomson, discoverer of the electron, Nobel laureate and President of the Royal Society, publicly hailed Einstein’s work as ‘one of the greatest – perhaps the greatest – of achievements in the history of human thought’. The drama of the occasion was undoubtedly heightened by the war that had just ended. A new theory of the universe, the brain-child of a German Jew working in Berlin, had been confirmed by an English Quaker on a small African island.

Figure 7.5. Einstein, the maker of a new universe, arrives in New York City in 1922.

Brown Brothers Agency, PA

The poignancy of these events was heightened a few days later by the Armistice celebrations in the streets of London, which recalled the euphoria that had greeted the end of the war a year before. The validation of Einstein’s theory by the confirmation of the predicted deflection of starlight had taken place under circumstances of high drama. At a time when nations were war-weary and heartsick, the bent rays of starlight had brightened a world in shadow, revealing a unity of humankind that transcended war. The deflected starlight had dazzled the public. But fate had played an unexpected trick – suddenly Einstein was world-famous. This essentially simple man, a cloistered seeker of cosmic beauty, was now an international icon, the focus of universal adoration.

Einstein’s elevation to something approaching sainthood started with headlines in the London Times. An article headed ‘The Fabric of the Universe’ explaining the Eddington expedition and its purpose, concluded that ‘It is confidently believed by the greatest experts that enough has been done to overthrow the certainty of ages and to require a new philosophy, one that will sweep away nearly all that has been hitherto accepted as the axiomatic basis of physical thought.’

The Times was not the only major newspaper to trumpet the general theory and Eddington’s eclipse expedition. The New York Times of Sunday, 9 November 1919, carried a three-column article under the headline ‘Eclipse Showed Gravity Variation: Hailed as Epoch-Making’. After describing the expedition, the article stated, ‘The evidence in favor of the gravitational bending of light was overwhelming, and there was a decidedly stronger case for the Einstein shift than for the Newtonian one.’ It went on to quote J. J. Thomson’s assessment of the experimental verification: ‘It is not a discovery of an outlying island, but of a whole continent of new scientific ideas of the greatest importance to some of the most fundamental questions connected with physics.’

Perhaps Eddington himself should be allowed the last word. An anecdote, which for many years was thought to be apocryphal, was confirmed by the physicist and Nobel laureate Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar in a memorial lecture on Eddington several years ago. The story was told to Chandrasekhar by Eddington himself. The story goes that as the November 1919 joint meeting of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society was breaking up, a reporter came up to Eddington and asked, ‘Professor Eddington, I hear that you are one of only three persons in the world who understand general relativity.’ Eddington, somewhat bemused, scratched his head. ‘Don’t be modest, Eddington,’ the reporter said. The unassuming professor replied, ‘Oh no, on the contrary, I am trying to think who the third person is.’

At the end of the second millennium it is now accepted that from this masterwork of Einstein’s have sprung all our modern ideas about cosmology. This includes the Big Bang theory, the expanding universe and stellar evolution. Discoveries of pulsars, quasars and black holes have eliminated all theories of gravitation save one, general relativity. Only now, as modern astrophysics probes deeper and deeper into space, are we coming to accept that we do indeed inhabit a curved universe, the one described by Einstein.

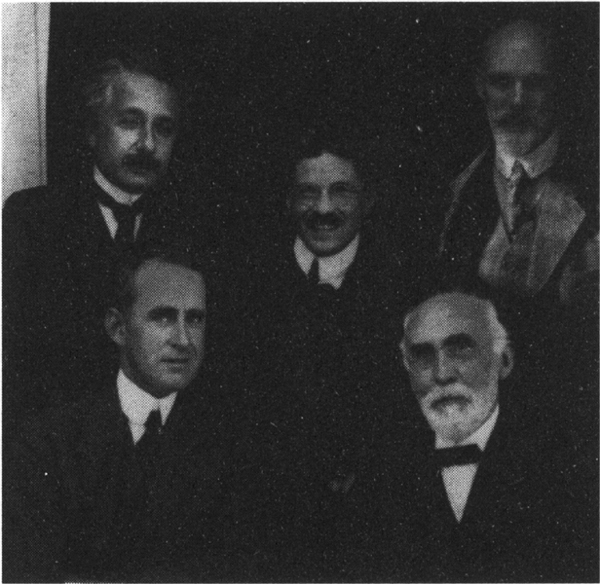

Figure 7.6. Eddington and Einstein meet for the first time, in Leiden in 1923 (clockwise: Einstein, Paul Ehrenfest, Willem de Sitter, Hendrik Lorentz and Eddington).

Akademisch Historisch Museum, Leiden

As solar eclipses continue through the twenty-first century and beyond, this story will be retold again and again. Certainly British scientists should never forget the pacifist Cambridge professor who, instead of peeling potatoes in May 1919, photographed the 32nd solar eclipse in saros cycle 136 from the island of Principe, and changed the world of physics and astronomy for ever.