5

THE MATING GAME

Crossbreeding from Day One

As for those genealogies which you have recounted to us . . . they are no better than the tales of children.

PLATO, TIMAEUS

The glut of inconsistencies and unsolved mysteries in the evolutionary family tree simply vanishes with an understanding of crossbreeding, one of the oldest habits of mankind. It is because man is and has always been a mixer that we so regularly find a striking combination of primitive and advanced traits in hominids. These mosaics are screaming hybridization, Homo hybridis, Homo cohabitensis. But are paleontologists listening?

We are all a complete mixture.

BRYAN SYKES, THE SEVEN DAUGHTERS OF EVE

Students and scholars alike are forever struggling with the relationship between the different fossil men. Well, that’s the right word. They had relationship, relations. Unthinkable? Not really. The hybridized “ascent of man”—which easily replaces the theory of evolution—is the other shoe about to drop on the scientific world.

Man is perhaps the most promiscuous animal . . . in the matter of indiscriminate interbreeding.

EARNEST HOOTON, UP FROM THE APE

IS NEANDERTHAL OUR ANCESTOR?

C. Loring Brace, representing America’s “pro-Neanderthal” school, and the Smithsonian’s Ales Hrdlicka, seized on Israel’s Mt. Carmel evidence to establish Neanderthal as forerunner of Homo sapiens. Other American scientists such as Franz Weidenreich and Milford Wolpoff also believed this to be so. Their European counterparts would have none of it. Neanderthal was merely some irrelevant distant cousin, for traces of mods earlier than Neanderthal came into existence, instantly disqualifying him as an ancestor.

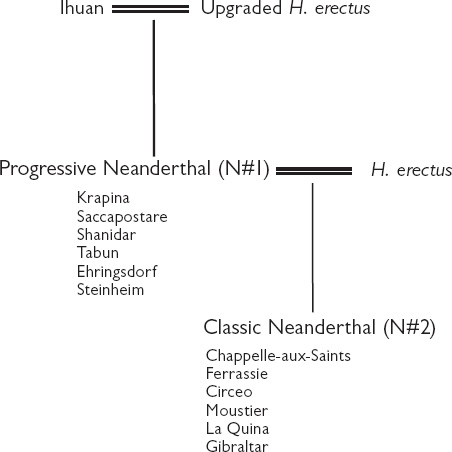

Earnest Hooton also pointed out that the time line was much too brief: How could “he have changed thus rapidly into modern man . . . in so brief a space of time”? Besides, Neanderthal’s brain was too large to be a phylogenetic link between low-order hominids and modern man—“a less credible miracle,” Hooton thought, “than the changing of water into wine.” Rather “radical race mixture [would be] . . . exactly the sort of phenomena that are shown in the skeletal series from the caves of Skuhl and Tabun in Palestine.”1 Hooton thought only the progressive Neanderthals stood a chance of evolving to moderns. (Two Neanderthal types have been discovered: a more robust specimen with a brutal continuous torus or visor called classic Neanderthal, which I call Neanderthal 2 [N#2], and a somewhat more refined, progressive type, which I designate Neanderthal 1 [N#1]. The more gracile Neanderthal 1 should, according to evolution, follow Neanderthal 2, but it actually came before.)

Wilfrid E. Le Gros Clark, for his part, thought the skeletal differences and “pattern of growth” in classic Neanderthals represented an isolated group not in the Homo line. Swiss workers (after making skull comparisons), concluded that Neanderthals belong to a separate species and did not give rise to living Europeans. More recently (2008) Germany-based geneticists, despite finding “no difference between Neanderthals and modern humans,” proceeded to argue that “Neanderthals were a separate species.”2

Mod traits have been found in Ethiopia before Neanderthals vanished from Europe and Asia. Neanderthal could not possibly have evolved into H. sapiens, as seen also at Dordogne, where a Cro-Magnon skeleton was found just above Neanderthal ones—a few thousand years is not enough time. Elsewhere in France mods at Combe Capelle and Mentone were again much too close in time to Neanderthals to have evolved from them: just as 35 kyr St. Cesaire Neanderthals could not have evolved in 3,000 years to 32 kyr Cro-Magnons.

The same situation applies to Grimaldi Man whose existence “in close association with the much more primitive Neanderthal form shows that Homo neanderthalensis could not be the ancestor of Homo sapiens, since both species were contemporary.”3 All told there is no real transition in Europe from Neanderthal to Cro-Magnon, the latter appearing not by evolution but quite suddenly.

Neanderthal, others argued, was too specialized to become anything else, no less modern man; and how could he be the ancestor of us all if his bones were basically confined to southern Europe (and adjacent western Asia)? Or if “fully modern men . . . lived in sub-Saharan Africa, Australia, and other areas of the world while the Neanderthals still inhabited Europe.”4 And he could not be our ancestor, if only because H. sapiens replaced or absorbed him in Europe rather than evolved from him (see chapter 12).

Even Thomas Henry Huxley, who would have loved to, could not see Neanderthal as an ancestor, because he was too much like us; though according to others, such as England’s Chris Stringer, Neanderthal was too different from us (especially in skull shape) to be our ancestor. (Go figure.)

But a way out of these difficulties was found—just create a common ancestor (out of thin air). Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck research team in Leipzig, declared: “We shared a common ancestor with the Neanderthal” before diverging from them, and evolving apart. But Neanderthal is simply, very simply, a retrobred race resulting from Ihuan (Cro-Magnon) “indiscretions.” He is not “pre-modern,” but actually post-modern, offspring of the back-breeding Cro-Magnons. Neanderthal owes his existence, not to any separating or splitting, but to a coming together of Ihuan and Druk. Marcellin Boule came very close to the truth when he suggested that Neanderthal “was a degenerate species.”

Let’s start with Neanderthal’s cohabitations and work our way back to the “affairs” of earlier times.

KISSING COUSINS: HIGHLIGHTS OF NEANDERTHAL DISCOVERIES

| 1829 | About two years before the young naturalist Charles Darwin sets sail on HMS Beagle, the very first Neanderthal skull is found in a cave in Belgium, that of a child. Within twenty years, further remains of a proto-Neanderthal woman and child are uncovered in Gibraltar, followed a few years later (in 1856) by the Dusseldorf/Feldhofer find, the German Neander Valley famously lending its name to the specimen christened Homo neanderthalensis in 1864. The limbs of this creature were bowed, the nose large, the brow bulging. Some saw it as merely a pathological modern, otherwise no different (except for robustness) than the rest of the human race. Indeed, that is his classification today: Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. |

| 1908 | With the discovery and examination of France’s La Chapelle-aux-Saints skull, French paleontologist Boule indignantly removes Neanderthal from the human family. The head, he thought, had too much in common with the chimpanzee—its cranium long and low, its brow prodigious. The “structural inferiority” of the toothless specimen too much offended his Gallic pride to be classed with men—despite an awesome brain of 1,625 cc, well over the modern average! The obvious answer, that a dose of Cro-Magnon (Ihuan) genes supplied the large brain, was not considered. At Shanidar, Iraq, Neanderthal’s cranial capacity was again well over 1,600 cc, outstripping our own, today’s average somewhere around 1,400. |

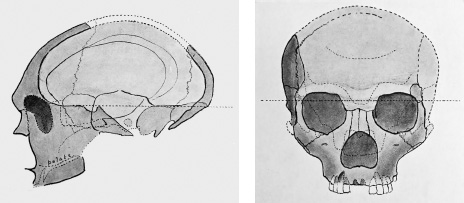

Figure 5.1. Two views of Gibraltar Man’s skull.

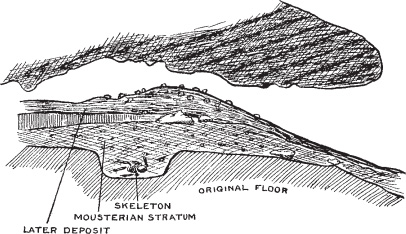

Figure 5.2. La Chapelle-aux-Saints skeleton and strata.

Figure 5.3. Marcellin Boule (1861–1942). To Boule, the idea of Neanderthal as our forerunner was “absurd.”

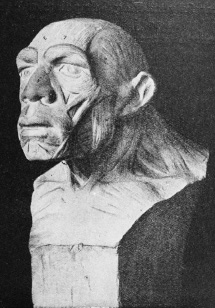

Figure 5.4. Neanderthal reconstruction, published by Marcellin Boule.

Figure 5.5. This reconstruction, published in L’Illustration in 1909, based on the work of Marcellin Boule certainly exaggerated the animalistic appearance of Neanderthal.

Figure 5.6. A more civilized portrait of Neanderthal from Illustrated London News, 1910.

| 1911 | To Arthur Keith, there was no reason to suppose that if Neanderthal and Homo sapiens mated, “they would not produce fertile offspring.”5 | |

| 1931 | Hooton stated simply, concerning Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon: “They surely bred.” | |

| 1937 | Back to France, where the Fontéchevade specimen is discovered, a Neanderthal evidently of the Mousterian period. However, the layer beneath held skull fragments of a more modern type, with lighter build and milder browridge; this at last was “the earliest Frenchman.” Yet the reversed sequence toppled the smooth evolutionary paradigm of gradual improvement over time. (See appendix E on reversals.) | |

| 1950 | Howells declares in Mankind So Far that “the Neanderthal brain was most positively and definitely not smaller than our own; and this is a rather bitter pill: it appears to have been perhaps a little larger.” | |

| 1955 | Le Gros Clark, esteemed Oxford professor of anatomy, in his book The Antecedents of Man tries to settle the mounting dilemma of reversals. To resolve the difficulty between Neanderthal 1 and 2, Le Gros Clark reasoned that the later Neanderthal 2 must have been isolated for a long time (due to climate conditions), which led to the differentiation. The older Neanderthal 1, mainly outside Europe, had a fairly well-developed forehead (absent in 2) and less massive jaws. The skull approximated that of H. sapiens, and the limb bones were also quite modern, being lighter and straighter than Neanderthal 2. In this case, Le Gros Clark astutely derived this man from an H. sapiens type with regressive changes in the skull, which he actually attributed to retrobreeding with a lower type. | |

| 1970s | Something called the spectrum hypotheses, introduced in this decade, admits much more interaction (sexual mixing) between different groups than we previously thought; indeed, the concept anticipates today’s theorists who are talking more and more of “gene exchanges,” though guardedly, catching up with Louis Leakey who, decades ago, had asked outright: “Is it not possible that they are all the result of crossbreeding between Homo sapiens and Homo erectus?”6 |

Figure 5.7. Author’s conception of crosses that produced the two different kinds of Neanderthals.

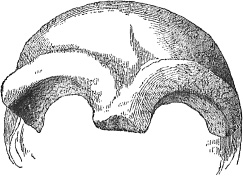

Figure 5.8. Torus. How can we call this brow “apelike” when orangutan is an ape, and it does not have a prominent torus; neither did some robust Au, such as Kromdraai, perhaps due to an admixture of AMH (Ihin) genes.

| 1986 | A twelve-year dig at Vindija Cave, Croatia, now completed, reveals that these Croat Neanderthals had sophisticated tools. Their skeletal structure was also a bit more delicate and modern than expected, which paleontologist Jacov Radovcic and others interpreted correctly as the result of interbreeding between Neanderthals and mods. Sure, many individuals had the ferocious browridge, sloping forehead, and powerful jaw of classic Neanderthal, but others had refined faces, cranial vaults, and limbs (matching similar finds in Italy). These Vindija people were dubbed “modernized Neanderthals”—a lovely euphemism for serious fraternizing. Normally Neanderthals among themselves look very much alike, though at Vindija there was considerable variation. How could this be explained? Further muddying the picture, the earliest mods at this location have numerous Neanderthal traits. | |

| 1988 | “The status of Neanderthals has changed more times than the mini-skirt has gone in and out of fashion,” quipped Roger Lewin in his 1988 book In the Age of Mankind. And now, on the slopes of Mt. Carmel, Israel, a mixed burial (studied actually since the 1930s) resurfaces to shake the family tree. Not too different from the Croatian sequence, Israel’s Qafzeh Cave revealed an early H. sapiens mixed in with others who looked considerably less modern. These Palestinian caves confirmed the coexistence of H. sapiens and Neanderthals. And with every variety of intergradation, crossbreeding (“signs of hybridization”7 at Skhul and Qafzeh) came into view. | |

| The fusion of types found in these Israeli caves (Tabun, Skhul, and Qafzeh) shows modern and Neanderthal traits freely admixed. Most have the trademark (heavy) torus, but variability of features is extensive, many specimens markedly modern in cranial vault, occiput, face size, and limbs. Yet those who posited the hybridization of these two different races are now silenced by a semantic ploy—labeling them Neanderthaloid, and arguing for a “transitional” stage of evolution. | ||

| Transitional? For goodness sake, these people were all living together! The fact, moreover, that the AMHs at Qafzeh were using Neanderthal tools makes us suspect that the main result of these crossings was retrogressive, that is, the back breeding of AMH-Ihuans into Neanderthal stock (which thereby inherited the Ihuan big brains). But to make them look “transitional,” paleontologists adjusted the date from the third interglacial to fourth; using C14, Tabun was dated 60 kyr and Skhul 35 kyr, making the Skhul population intermediate (transitional between Neanderthal and mod), thus “eliminate[ing] all need for theories involving hybridization, with their attendant difficulties.”8 Despite these maneuvers, Ashley Montagu saw here a clear “intermixture between a modernlike form and Neanderthal. . . . The Mount Carmel population was the product of that intermixture. There is every reason to believe that similar intermixture (hybridization) occurred between populations throughout the long prehistory of man.”9 [e.a.] | ||

| Making matters worse for the evolutionist, at Mt. Carmel, as in France in 1937, H. sapiens was older than Neanderthal. Indeed, a similar out sequence was observed at Steinheim, Swanscombe, Ehringsdorf, Krapina, and other sites, where the more gracile Neanderthal (Neanderthal 1) preceded the more extreme, “chimpanzee-like” one (Neanderthal 2). | ||

| 1992 | Speaking of chimpanzees, in his book released this year, The Third Chimpanzee, Jared Diamond confidently declares (despite Carmel and Vindija), “No skeletons that could reasonably be considered Neanderthal-Cro-Magnon hybrids are known.” Yet that same year, fossils in Spain (Atapuerca) prove to be a farrago of H. erectus, Neanderthal, and H. sapiens traits! “There could have been a big party of different hominids living in Europe together,” offers archaeologist Clive Gamble.10 And now there is further evidence from other parts of Europe that Neanderthal and early mods (Cro-Magnon) partied together: at Mladec, Czechoslovakia; Steinheim, Germany; and Muierii, Romania. | |

| 1996 | This year, Donald Johanson and Blake Edgar publish their lavish book From Lucy to Language, informing us that Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon “were too biologically distinct to have shared anything more than culture.”11 Others, though, were indeed floating hybridization to explain the softened features of St. Cesaire’s Neanderthals, especially since excellent Cro-Magnon tools were found there as well as at another French Neanderthal site: Arcysur-Cure. Further confusing the issue, Johanson and Edgar state: “Even if it [meaning: interbreeding] did happen rarely, it would not mean that Neanderthals and modern humans were a single species”—a downright contrarian position, defying the very definition of species, as I will soon make clear. | |

| 1997 | Hominid Paleogenomics takes the stage by storm, as biologists are now equipped to analyze the Neanderthal genome in earnest: wherein the Max Planck (a group of reknowned scientific research institutes) people supposedly deal “a powerful blow” to the interbreeding idea. If it happened at all, “it was too rare to leave a trace of Neanderthal DNA in the cells of living people.”12 Also in 1997, Chris Stringer of London’s Natural History Museum agrees that Neanderthal are “probably” a different species. Not a good bet, as we will soon see. | |

| 1998 | For, now a small and stocky breed of 24 kyr people has been discovered at Abrigo do Lagar Velho, Portugal; it is a child’s skeleton, presenting a striking blend of mod and Neanderthal traits—thousands of years after the latter supposedly went extinct. While the child’s teeth and chin are modern enough, the jaw is heavy and short, the bones thick, forcing some to reluctantly concede that there could have been “significant interbreeding” between Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon here. Others, though, hold to “the complete absence of any Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA in modern Europe. . . . [I]f this interbreeding were a frequent occurrence, then surely we would see the evidence in the modern mitochondrial gene pool, and we just don’t.”13 This comment is almost immediately contradicted by new updates that say 4 percent of the DNA in Europeans and Asians appears to be derived from Neanderthals, due to hybridization. Paleoanthropologist Milford Wolpoff concurs: Neanderthal DNA falls within the modern type. | |

| 1999 | Following up on the controversial Portugal discovery, paleoanthropologist Erik Trinkaus of Washington University, St. Louis, points out that Portugal’s 24,000-year-old boy is a blend of mod and Neanderthal, but hedges: “the boy could simply be the love child from a single prehistoric one-night stand.” Ian Tattersall of the American Museum of Natural History, also playing down the rising specter of crossbreeding, remarks: “It’s just a chunky modern kid. There’s nothing special about it.”14 After all, too much interbreeding, and the house of evolution all falls down. | |

| 2000 | Tattersall goes on to cite DNA evidence confirming that the human race does not bear any biological connection to the Neanderthal “species.” | |

| 2002–3 | But a new trend is afoot, and now a dig at Pestera cu Oase (Cave of Bones) in Romania comes up with more hybrids, H. sapiens sporting unmistakable Neanderthal features: huge long noses, great molars, occipital buns. Dated anywhere from 30 to 40 kya, the mandible is robust but combines archaic and mod features. The specimens are clearly of mixed type. Four years later (in 2007) when digs in Czechoslovakia come up with similar results, the finds once again whisper of repeated dalliance between modern humans (Cro-Magnon Ihuans) and Neanderthals (more than a onenight stand). Nevertheless, Richard Klein, teamed up with Blake Edgar in The Dawn of Human Culture, assures us that “if Cro-Magnon and Neanderthals interbred, it was probably on a very small scale.”15 The same year sees Stephen Oppenheimer, in The Real Eve, asserting that “no genetic traces of them [Neanderthals] remain in living humans.”16 But all our naysayers will soon be eating crow. | |

| 2006 | In November, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, emboldened by recent progress in paleogenomics (using 38,000-year-old DNA), issues a press release asserting that Neanderthal and ancient mods were not likely to have interbred. Even though they coexisted, say these scientists, there is no evidence of significant crossing. But that same year, paleoanthropologist Erik Trinkaus reenters the fray, reminding us of definite hybrids discovered in southwest Romania (in 1952), comparable to the 40,000-year-old Romanian cave skull (found in 2002), which has been classed as basically modern, though the forehead is extremely long and flat, and the molars very large. Trinkaus, as before, manages to cover both possibilities by stating that interbreeding would not be a “surprise.” But very shortly after, as the evidence mounts, the professor loosens up: “Why not? Humans are not known to be choosy. Sex happens.”17 Indeed, a separate study that year finds a haplotype in these 40,000-year-old genes that may have been passed on during an “encounter” with Neanderthals. | |

| 2007 | Discover magazine runs a piece that mentions that “our ancestors may have gotten up to 25 percent of their DNA from Neanderthals.”18 | |

| 2008 | Despite the theoretical crisis caused by all this unevolutionary nookie, genome researchers at Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig doggedly maintain that Neanderthal mtDNA falls outside the range of human variation, indicating an entirely separate species—even though Neanderthal and H. sapiens share about 99.5 percent of DNA! Cautiously, however, the team asserts that this doesn’t mean crossbreeding would have been impossible. Hybridization, though now out of the bag, must still be made to play a minor role.*72 Thus do these scientists, now working on 70 percent of 40,000-year-old Croatian DNA, say that so far the project has unearthed no sign of DNA transfer between the two hominid lineages. | |

| Nature magazine is quick to cover the story, parroting that Neanderthals probably did not interbreed with their “human” neighbors. Scientific American publishes similar findings but does mention the alternative multiregional model of occasional interbreeding, which Wolpoff has been saying all along, citing, for example, the especially modern jaw structure (mandibular nerve) of Neanderthals. Meanwhile, the Max Planck people, evidently sniffing a change in the wind, are now quoted as saying “some gene exchange might [e.a.] have occurred, but the result was later found to have been a false signal because of sample contamination.”19 Other publications in 2008 backed up this stalwart conclusion, such as Ker Than in National Geographic.20 Also, in their 2008 book, Human Origins, Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall stand by the agenda: “the two kinds of hominid did not mingle. . . . Neanderthals and moderns represented two distinct species, and thus would not have effectively interbred.”21 | ||

| 2009 | Leading a Max Plank team, Pääbo, having successfully recovered 60 percent of the Neanderthal genome, affirms his earlier assessment of no “significant” evidence of crossbreeding. | |

| 2010 | “DNA has even shown that a few [e.a.] Neandertals interbred with our ancestors,” reports now allow. The thing is, we now have data on the coloring of these specimens and lo and behold, some Neanderthals had red hair and pale skin. Well, of course they did; all the races, past and present, have some Ihin traits—be it fair complexion, mod brain, slender build, or other AMH characteristics. But Douglas Palmer’s book, Origins: Human Evolution Revealed, published in 2010, backs up the naysayers, agreeing that one finds “no genetic mixing between Neanderthals and modern humans.” | |

| Pääbo, blowing hot and cold, first stresses that there is no sign of admixture. Using sequences of nucleotides, he notes that Neanderthal mtDNA is “readily distinguishable” from mods. But things are changing fast and by May 2010 the Pääboled Max Planck team changes its conclusion, acknowledging that interbreeding probably occurred: the “team’s second conclusion—[huh?]—is that there was probably interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans. . . . Neanderthals mated with some modern humans, after all.”22 Non-African moderns, it is now discovered, have 1 to 4 percent Neanderthal genes. Nevertheless they are still telling us that Neanderthal DNA does not seem to have played an important role in human evolution, although interbreeding “would not be greatly surprising, given that the [two] species overlapped from 44,000 . . . to 30,000 years ago.”23 | ||

| By October of 2010, an article titled “Human Family Tree Gets Bushy, Grows Roots” appears in Discover magazine relating “one stunner: early humans mated with Neanderthals” according to genetic studies (using DNA fragments from Neanderthal bones). Pääbo can now trace that interbreeding back 60,000 years to the Middle East. Now he says “humans and Neanderthals must have mated at some point.” | ||

| 2011 | Discover magazine, in January, lures readers with “Stone-Age Romeos and Juliets,” the piece confirming that “Neanderthals and modern humans probably had interbred . . . at least once.” Only once? Now, earnest paleoanthropologists, poised like concerned parents of wayward teens, promise to “pin down how much interbreeding occurred.” Then, in May, Discover returns to the subject: “Maybe we all carry a bit of Neanderthal in our DNA,” although the differences presumably “are great enough to rule out significant interbreeding.” So paleogenetic DNA sequencing has now established that AMHs “interbred with Homo neanderthalensis . . . in the Middle East. . . . We shared the planet with our cousins.”24 But not just in the Middle East . . . | |

| Finally, as if to make it all OK and respectable that our ancestors fooled around with lowly Neanderthals: “First modern humans protected themselves against disease after leaving Africa by interbreeding with Neanderthals. . . . Early humans picked up genes which protected them . . . and eventually helped them to populate the planet.”25 (So nookie with the cavemen wasn’t all that bad.) |

DIVERGED OR MERGED?

Since Darwin’s day, many missing links were found—creatures that seem to link Au to H. erectus, H. erectus to Neanderthal, and so on. So what was the problem? Something in the morphology of these intermediate types, the links, always precluded a smooth sequence from one to the other. Always something that doesn’t fit. It is, some have commented, as if these mosaics were all made of spare parts. Each fossil seems to combine the laundry list of morphological traits in a different way, ruining the flow from one to the other. Lee Berger’s Au. sedipa, for example, is “a jumble of parts.” A spot note in Smithsonian titled “Body Parts” refers to our “idiosyncratic histories” and the idea that H. erectus is made out of “different parts. . . . It is amazing what evolution has made out of bits and pieces.”26 But is it evolution that jumbles spare parts, or simply crossbreeding?

“The nookie factor,” the whimsical term coined by my friend, archaeologist Chris Hardaker, gives us a much better idea of these spare parts: a picture of melting pot Earth, mix-and-match humanity with the urge to merge since day one, which is the only honest solution to the so-called transitional and mosaic types that abound in the fossil record. The hybrid model of man’s lineage does not look for an ancestor but for (at least) two ancestors. In the words of Franz Weidenreich: Most populations have several ancestors.

Paleontologists have, to date, assembled many fossil men, both primitive and more advanced, but can reach no agreement on sequence, how these fossils relate to each other, most critically how or if one is ancestral to the other. But let’s streamline the whole shooting match: Think of the endless quibbling, even ungentlemanly rancor, over hominid classification—deciding which taxon specimens belong to—when mixing, plain and flat, is the magic bullet, Occam’s razor. Parsimony par excellence.

Think of how things will slip into place if early (second race, Ihin) is recognized as the source of all small, gracile, and big-brained specimens. The late nineteenth-century German biologist, geneticist, and zoologist August Weismann laid out a fundamental principle, the law of parsimony (though he didn’t follow it himself), demanding that extraneous forces not be invoked. Weismann thought Darwinism leaned too much on unknown factors, hypothetical forces. Account for phenomena that can be readily explained by known causes, Weismann argued. Well now we know . . . about hybridization.

Parsimony also means the fewer assumptions made, the better the theory. It is a kind of thrifty, minimalist thing: the more a single axiom or fact can account for a wide range of phenomena, the truer it rings. This way, too, we remove the paradox of polygenesis: the problem being—How could races all over the world have coincidentally evolved in the same way? This difficulty evaporates once we recognize the Asu-Ihin-Druk blends in all parts of the world. It has been asked, for example: If a single mutation of a gene could change the length of limbs, why is this “random” mutation the same in far different places? Obviously, there is something amiss in our searchlight. Nothing ever “changed” the length of limbs; gene flow (race mixture) alone brought about such differences.

Milford Wolpoff in Race and Human Evolution incisively points out that the same DNA variations “are found over and over again, in the most widely separated populations.” How is that possible? How could they all evolve the same way? The answer is profoundly simple: They didn’t. The same basic types intermixed; they did not evolve.

Follow these hybrids dispassionately and we also dissolve the decades-old debate of why bipedalism appears to have preceded big brain. Lucy, for example, was bipedal but pea-brained; Taung Child also was bipedal with the “brain of an ape.” And why was Taung’s foramen magnum and dentition more advanced than his jaw and face? Mixing is the answer. All the mixed traits in these australopiths (see table 1.1) devolve quite simply on their mixed parentage.

Differences between H. rudolfensis and H. habilis (the two were contemporaries in Africa) have been ascribed to “rapid evolution.” Nonsense. It is simply a matter of two races blending, consorting—and in a matter of generations producing a new type. Why call the time between H. habilis and H. erectus “rapid hominid evolution,” when it is plain that mixing gets even quicker results—with no evolution in sight? Besides, it was too big a change in size/stature for H. habilis (a bit over three feet) to evolve into creatures like tall and lanky Turkana Boy. Did H. erectus evolve at all? Not really. They appeared suddenly. Neither did they “lead” to higher forms:

Figure 5.9. A shot at hybridization. A grapefruit chastising an orange for cheating on her husband, having two children—a tangerine and an apple. Cartoon by Marvin E. Herring.

Nowhere can it be demonstrated that men of the Homo erectus grade did evolve into modern populations.

J. B. BIRDSELL, HUMAN EVOLUTION: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY

Zoologist T. Dobzhansky had no problem accepting hybridization among human populations throughout the Pleistocene. Crossbreeding readily explains the so-called rapid evolution of certain fossil men, the inexplicable quantum leaps in the record (evolution’s big bangs or explosions). From the Au lineage a new “species” rapidly became much larger, brain size increased dramatically. No, this is not evolution. This is something else.

In the plant kingdom it was found that primroses made similar jumps, not by Darwinian mutations, but simply by hybridization, producing traits the parents did not have. Breeders have obtained plants and animals so surprisingly different, they would be immediately classed as a different species entirely if found in the wild. Hooton, discussing the appearance of very tall and raw-boned men, wrote “I have no doubt . . . [they] owe their increased size and ruggedness . . . to heterosis or hybrid vigor. . . . [I]n a world of men who have been migratory and promiscuous for scores of thousands of years, the origin of new types through hybridization . . . and recombinations . . . is a much more likely phenomenon than pure line ancient forms. . . . Hybrid vigor . . . means an increase in size and strength. . . . [M]ost of the tallest human groups are of mixed racial origin.”27

ROOM OF MIRRORS

By general definition, a species is a breeding group that does not or rather cannot productively mate with any other group. Even if they do mate and there are offspring, the latter are infertile. Sometimes, though, it is difficult to know where one species leaves off and another begins. When it comes to wolves and coyotes, for instance, it is hard to say quite where one “species” stops and another starts, because wolves and coyotes can successfully breed. They should not, therefore, be called different species.

You could say zoology, like paleoanthropology, has become species happy. Even among the thirteen supposedly distinct species of Darwin’s Galapagos finches (see figure 4.8), some do interbreed; just as there are two supposedly different species of Mexican howler monkeys that still mate with each other. Even lions and tigers have interbred (in a zoo): if the father is a lion, the cub is called a liger; if the sire is a tiger, it is a tigon.

What about the human species? William Howells held that humanity has always been a single species (therefore interfertile), even though separated geographically. T. Dobzhansky was another who protested the unnecessary multiplication of species and genera for hominids; let them all be one species and one genus Homo. Though correct, this is today a minority opinion.

For many years it was argued that Neanderthal was a different species from us; H. erectus also was considered, by some, not only a different species but also a separate genus from Homo. Richard Leakey, wisely, thought that H. erectus and H. sapiens were not only the same genus but also the same species, H. erectus but an early version of H. sapiens. His father, Louis, toward the end of his long career, even asked if crossings could not in fact account for the multifarious H. sapiens–H. erectus composites so puzzling to analysts. Nor did Coon or Weidenreich rule out the interfertility of these two types of men: AMH and Druk.

As an example of the oxymoronic confusion bedeviling these matters are statements like: “Neanderthals and modern humans are separate species, but do not rule out some interbreeding.”28 If they could interbreed, and did interbreed (with fertile offspring), we have no business calling them different species; they would be merely different races (subspecies). Also violating the definition are statements like: “Once we shared the planet with other human species, competing with them and interbreeding with them.”29 Come again? I thought different species don’t interbreed by definition!

The very concept of species has been debated for decades, with no final agreement among biologists on what species are. Are they simply a gene pool, meaning closely related populations who reproduce with one another? In the event that they don’t interbreed (like different “species” of fruit flies that look exactly alike), it doesn’t mean that they can’t. Separate gene pools may not be such a good criterion; the Bushmen, for example, comprise a separate gene pool from Eskimo-Inuit and don’t exchange genes with them, but still both are of the same species. We should follow Ernst Mayr in this regard, defining species according to their interbreeding potential.

Weidenreich, noting the “irresistible trend to interbreed” among humans, recognized that all people were cross-fertile, that they can, do, and did, crossbreed, this ability proving we are all one species. Indeed, one might even “eliminate all the generic names”30 of fossil man,*73 as far as he was concerned. Although his insight goes back seventy-plus years, I believe it is the correct one, yet it is disparagingly labeled “already in disrepute”31 by some of today’s leading evolutionists.

Officially, H. erectus and H. sapiens couldn’t interbreed because they are (taxonomically) classed as different species. But they did breed together, producing viable, fertile offspring, such as Homo floresiensis, the small-bodied fossils found in Palau, and Broken Hill Man (see chapter 11), where a combination of H. erectus and H. sapiens traits are all too apparent. The Palauans of Oceania were the same size as small Au, yet some of these Micronesian fossils are as recent as 1,400 years old, and certain craniofacial features are in keeping with H. sapiens. As for Zimbabwe’s Broken Hill Man, he possessed a large brain and gracile limbs, though his face and skull resembled Neanderthal and H. erectus. Some then called it Neanderthaloid, but with such mixed features, scholars argued back and forth whether to classify it as H. sapiens or Neanderthal. Europe’s H. heidelbergensis was another who represented a marvelous alloy of H. erectus, Neanderthal, and H. sapiens traits. In fact, H. erectus almost everywhere has been found with H. sapiens traits sprinkled in, such as in Europe where a mosaic of features abounds—not to mention H. erectus–mod blends in the Far East, at Choukoutien and Ngandong. And in Africa: mixed in one creature, Homo ergaster (Skull KNM-ER 3733) are massive (archaic) features along with thin bones and modern nasal structure. Students of the African hominids have noted “the puzzling variability in early Homo.”32 Of course there’s variation! It is not puzzling; that’s what happens when races mix. No, variability is not “hiding in the genes”; nor is it DNA “mutations” that generate variability. All we are seeing are the mix-and-match results of crossbreeding. We have taken infinitesimal measurements with calipers and run endless computer programs, and argued about classification till the cows come home. But there is and has always been only one species of man on Earth, different kinds for sure, but all assorted members of the family of man.

In an e-mail, archaeologist Christopher Hardaker told me they edited out the following portion from his 2007 book The First American: “By definition, a people cannot successfully mate and have viable offspring with another species. . . . There might be nookie but no babies. . . . If babies, then same species. . . . How does ‘H. erectus sapiens’ sound? If everyone from H. erectus forward could ‘do it’ with everyone else, it would certainly give an added dimension to the name erectus. . . . You are warned on the first day of Phys Anth 101 that the world of human evolution is divided into splitters and lumpers . . . [but] it is a room of mirrors.”

A NEW RACE WAS BORN

If you want to get really confused, make a close study of who’s who in the human fossil family. Paleontologists keep changing their mind as to who belongs in the genus Homo. The earliest candidates, Africa’s australopithecines, were a bewildering hodgepodge of human and subhuman. East Africa’s Olduvai and Turkana finds were so “varied and baffling” that debate raged for decades over their proper classification.33 All that fussing and fighting, when they were, after all, nothing but hybrids—as were their parents and grandparents.

At sites like Torralba, Spain, and Olorgesailie, Kenya, large numbers of primitive and sophisticated tools (flake and core-bifaces, respectively) occur together in open-air sites. And when H. erectus tools were found mixed in with more primitive ones at Olduvai Bed II, some analysts were forthright enough to say it looked like a case of “interbreeding. . . . The two gene pools are completely mixed. . . . This sort of interaction must have happened many times during the course of human evolution.”34

How will Darwinian phylogenesis stand up to the lack of evidence for H. erectus evolving to H. sapiens? According to Ian Tattersall, a method called cladistic analysis does not allow it; according to Birdsell, brain size difference does not allow it. And if so, there is no evolution either, for with Neanderthal eliminated as our ancestor that leaves only H. erectus to fill the slot. Neither was Louis Leakey convinced that the pithecanthropines led to H. sapiens, his opinion based on morphology of the skull and H. erectus’s huge visor or torus, so tremendous it strains even the most credulous imagination to see in it the precursor of man. Meanwhile Marvin L. Lubenow has decried the wholesale ignoring of the Selenka-Trinil expedition, which found that mods and pithecanthropines lived at the very same time in Java, the latter playing no part in human evolution. “It is an amazing conspiracy of silence,” comments Lubenow. 35

In Hindu scripture it is written: “the first race Asu [Ardi] tempted the white people”*74 In other words, the Ihins broke the commandment of endogamy (in-marriage) which enjoined: “Neither shall ye permit the Ihins to dwell with Asu, lest his seed go down in darkness.”†75 But the little people strayed out of the Garden of Paradise and “began to dwell with the Asuans, and there was born into the world a new race, the third race of man, called Druk [a.k.a. Cain a.k.a. Homo erectus], and they had not the light of the father in them, neither could they be inspired with heavenly things.”‡76 And the Druks were the first people to go to war, hence Cain’s “mark of blood” in the Old Testament.

Those of the lesser light were called Cain (Druk), because their trust was more in corporeal than in spiritual things; and those with the higher light were called Faithists (led by Ihins) because they perceived that Wisdom shaped all things and ruled to the ultimate glory of the All One.§77

Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, H. erectus is still widely considered our immediate ancestor, but he is nothing more than the result of Ihin-Asu “interaction.” If neither Au nor H. erectus is ancestral to us, then what? It’s the nookie factor, for the Ihins repeatedly blended with the autochthonous races. Wherever short stature, smooth features, gracile build, or unpredictably modern crania are observed in otherwise archaic forms, Ihin genes are at play.

LUMPERS AND SPLITTERS

Darwin mentioned theorists who envision anywhere from two to sixty different species of man. Well, the more they dig, the more mixes they find, erroneously calling them species—and gloating over the everexpanding variety of human and prehuman species. Yet critics do ask: “Is it possible that the scientists, who have given new species names to every early Homo find with significant differences, have made our family tree more complicated than it really is?”36

Indeed, the “lumpers” (including Thomas Henry Huxley, T. Dobzhansky, George Gaylord Simpson, Franz Weidenreich, and Ernst Mayr) all have argued against this unnecessary proliferation of species. Let all hominids be one species. It’s the splitters who gave us 700 species of Drosophila and 13 species of Galapagos finches, when they may just be varieties or races (subspecies); according to Mayr, there is extensive hybridization among six of those “species” of finches. “[You] might as well have called them all one species,” says another analyst.37 Fact is, Darwin himself thought the finches were merely varieties, until the ornithologist John Gould convinced him they were separate species!

But that’s birds; what about man? The fundamental design of the human cranium is the same from the earliest pithecanthropines right up to the modern races. These features, they say, vary among recent races as much as between different fossil types; therefore, we might just as well split up recent man into several species—which would be a falsehood. (If a bone man were to compare the morphology of an African Khoikhoi and a Swede, without knowing the source of the specimens, he might well designate them as different species.)

Multiple human species—no; multiple races—yes.

The fossil people are trifling with us: a slightly different shaped jaw—and presto!—a new species is born. This was the scenario when Lucy’s discoverers assigned her to a different species than Au. africanus, who had slightly more specialized teeth. But they were not different species, only different proportions of Asu and Ihin genetic makeup. (C. Loring Brace thought the teeth of the two not very different.) Splitters continue to confuse the issue by seizing on minor differences, boldly naming a new species based on one or two fragments.

Richard Milton, in Shattering the Myths of Darwinism, reminds us that a few years after Louis Leakey “insisted that his discovery [of Zinj] was entirely novel,” it was found to be just another robust Au. Also in East Africa, Ethiopia’s Ardipithecus kadabba, although known only from fragments, was made the “probable ancestor” of Ar. ramidus. Originally considered a subspecies (race only), the older Ardi was now elevated to Ar. kadabba, a new species, on the basis of bone scraps and a few teeth with a slightly different wear pattern than Ar. ramidus. Are different teeth really enough to crank out a brand-new species?

The splitters are a determined lot, telling us that “the notion that multiple human species are the norm . . . has only got stronger with a series of major scientific discoveries. Since 1994, four new species [e.a.] of hominid have been added to the human family tree.”38 But rather than species, these are simply different races.

Built into anthro-speak is a slippery, disorienting use of this term species, where only races apply. Even Stephen J. Gould, the late-twentieth-century darling of paleontology, couldn’t get it right: “Before commerce and migration mixed us up, each race is a separate biological species.”39 This is a contradiction in terms! We ought to remove Neanderthal from our species, Gould also argued—in agreement with Tattersall, a consummate splitter, who urges that Neanderthal be restored to separate species status, ignoring the now incontestable evidence that they interbred productively with mods. And how about this: J. B. S. Haldane, the esteemed English biochemist and founder of the new synthesis (neo-Darwinism) said “new species may arise by hybridization.”40 Well, in that case we don’t need evolution at all. England’s Douglas Palmer counts at least twenty species among our ancestors, again using “species,” where really only race (subspecies) applies. In fact many of these “species” are not even distinct races—just variations, strains, crosses, mongrels.

A recent discovery in Africa, honored with a new species name, Australopithecus sedipa, was presented to the world with all the fanfare of an exciting new discovery who will “rewrite long-standing theories.” Dated to about two million years, it was initially hailed as our direct ancestor. However, critics say Au. sedipa actually came after H. habilis and hence is too young to be our ancestor. All the while Au. sedipa screams hybrid—nothing but an upgraded Au. Found in 2008 near Johannesburg, this creature is made of “spare parts,” said to be an “odd blend . . . head-to-foot combination of features of Australopithecus and the human genus, Homo.”41 And, yes, it is just that. Testifying to Ihin genes are: reorganized front brain, projecting nose, smaller teeth, humanlike hips and pelvis, longer legs, and precision grip.

In 2010, when they found “distinct” mtDNA in the Siberian Denisova remains (it was only part of a pinky finger), it instantly became a new species. Assigning new species to every new fossil, sometimes named after the finder or the sponsor, is like having a star named after you. After all, there is little hope of hitting the news with mere varieties or races; only new species will do the trick. One paleontologist decried “the rashest statements in the face of evidence . . . generalizing on single observations. . . . Journalism, my dear boy, journalism pure and simple.”42 With Denisova, the glory went to the geneticists, the finger fragment supposedly “marking an entirely new group of ancestral humans.”43

All these new species create “a terrible paleontological mess. . . .Everyone who had a fossil come into their hands . . . wanted it to be something new . . . for their purposes of self-aggrandizement. . . . Some were unhappy when their prize species were lumped together with those that others had discovered.”44

Weidenreich, one of the best minds in the game (“that masterly student of ancient man,” according to Hooton45), was right to warn that raising the differences between racial groups to the rank of species is artificial, an illusion, a “taxonomic trick,” exaggerating dissimilarities to make your find important. Like Weidenreich, Dixon and Hooton explained the confusing varieties of man simply, parsimoniously, by way of amalgamation. Harvard supported this for a while, though the debate fired up again: Were races actually species (splitters) or just variants (lumpers)?; today you get as many opinions as professors. Interfertility, for example, is quibbled with and not always considered a perfect criterion for species inclusion. (Significantly, it is biologists—not taxonomists—who are satisfied with using interfertility as the best available guide to define species.)

Darwin muddied the picture with floundering logic, arguing that even if all human races are interfertile, still this is not a safe criterion for single species. These matters, he said, are governed by “highly complex laws . . . a naturalist might feel himself fully justified in ranking the races of man as distinct species, for . . . they are distinguished by many differences in structure. . . . The enormous range of man . . . is a great anomaly in the class of mammals, if mankind be viewed as a single species. . . . The mutual fertility of all the races has not as yet been fully proved.”46 It took the twentieth century—with its uptick in racial blending—to prove it.

[No] animals very different will breed together.

CHARLES DARWIN, NOTEBOOK C

It is a fact, too, that some species that look quite distinct interbreed regularly.

Frankly, Darwin’s ideas on fertility and sterility of hybrids came mostly from his study of flowers. Though he denied it for man, he did note the increased fertility of crossbred flowers.

CUTE IN THEIR OWN WAY

Whenever the populations of early man met they did exactly what modern populations do, they interbred.

ASHLEY MONTAGU, MAN: HIS FIRST TWO MILLION YEARS

Perhaps there is some ingrained repugnance at the idea of elegant AMHs mating with clumsy cavemen, even though the Indo-Europeans, our forebears, “spread across the world . . . interbreeding with peoples of the most diverse hues and features.”47 Tattersall, a great splitter, thinks we’re much too fine to be lumped together with the early hominids: “Our own living species, Homo sapiens, is as distinctive an entity as exists on the face of Earth, and should be dignified as such instead of being adulterated with every reasonably large-brained hominid fossil that happened to come along.”48

In fact, I suspect a hidden factor behind the slow acceptance of amalgamation as the true ascent of man: xenophobic bigotry. Awarding species status to mere race differences may be part of a lingering deepseated racialism that views these differences as irreconcilable and unassimilable, the same spirit of apartheid that invented and used the word miscegenation to denote interracial marriage.

Tattersall goes on to bolster his claim with the argument that “Neanderthals . . . and Homo sapiens would probably not have recognized each other as very desirable mating partners.”49 “Few Cro-Magnons may have wanted to mate with Neanderthals,” agrees Jared Diamond, who supposes that “the differences may have been a mutual turnoff . . . [H]ybridization occurred rarely if ever . . . [one] doubts that living people of European descent carry any Neanderthal genes.”50 Cro-Magnon, say others, regarded uncouth Neanderthal as “little more than animals.”51

Despite these parochial opinions, the fact remains that “race pride or the differences of religion and customs have never prevented the Anglo-Saxons from crossing with the lowest of savages,” as Armand de Quatrefages made bold to assert in The Pygmies. Let’s not allow our puritanical or other views to blind us to these liaisons. Highbrow and lowbrow have somehow always bridged the gap; folks from opposite sides of the track, so to speak, have always been drawn together across the divide. “One thing human beings don’t do,” observed prehistorian/anthropologist/archaeologist Robert Braidwood, “and never have done, is to mate for purity.”52

Franz Weidenreich, in Apes, Giants, and Man, also stressed “the tendency of man to interbreed without any regard to existing racial difference. This is so today . . . and there is no reason to believe that man was more exclusive in this respect in still earlier times.” And who knows, some of these hybrids might have been quite fetching. Hey, if high cheekbones and full lips were in then, as they are now, no telling what these mosaics looked like. Writers are beginning to ask if the Neanderthals “were the ugly brutes often portrayed by popular science, or were they cute in their own way?”53 (Some had freckles.)

Figure 5.10. Mixed Fijian. In the Fiji archipelago Polynesians and Negritos crossed in all degrees.

Historically, some of the most backward people have mated with more sophisticated tribes: Alpheus H. Verrill reported that “the living Indians of these districts [Nicoya, Chiriqui, Terriba, in South America] are the result of mixtures of the cultured races and the more savage tribes.”54 In Brazil, Percy Harrison Fawcett thought the Morcegos (see chapter 12) and their kindred the “most bestial and degenerate savages in existence,” yet some of them intermarried with the more noble Tupis and Caribs, and from this amalgamation sprang two different types, the Botocudos (“Neanderthaloid in type,” according to Czech anthropologist Ales Hrdlicka) and the extremely varied Aymaras. This region also had milk-white Indians, their skin covered with short down, who saw best in moonlight; those mooneyed types are of extraordinarily composite heritage.

| TABLE 5.1. SIGNS OF CROSSBREEDING: MIXED MORPHOLOGY AMONG EUROPEAN FOSSIL MEN | ||

| Where/What | Modern Traits | Archaic Traits |

| Croatia/Krapina Man*78 | Frontal region, Beetle brow, sloping forehead, great jaw, large face and orbits, barrel chest | 1,300–1,500 cc, brachycephalic, limbs mod, light build |

| France/Arago Man | “A fascinating mosaic of old and new features”†79 | |

| France/Fontéchevade Man | High forehead, 1,400 cc, light build | Heavy browridges |

| France/La Chapelle Man | Big brain: 1,625 cc | Heavy browridges, long and low cranium |

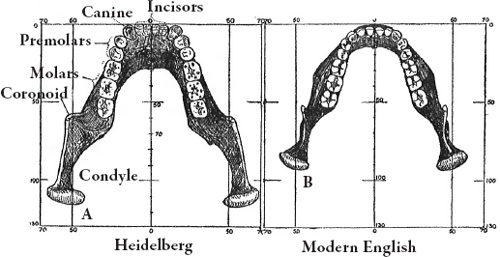

| Germany/Heidelberg Man | Modern dentition | Massive mandible, broad jaw, no chin |

| Greece/Petralona Man | “Hints of modernity” | “Distinctly primitive”‡80 |

| Germany/Steinheim Man | Well-developed forehead | Heavy browridges |

| Hungary/Vertesszollos Man | Some modern features, 1,500 cc | Thick and broad cranium |

| Portugal/skeleton | Modern chin and teeth | Thick bones, short legs, hefty jaw Romania/skull Modern

skull Long and flat forehead, large molars |

| Spain/Atapuerca Man | Modern chin | Heidelbergensis in type |

| UK/Swanscombe Man | Big brain: 1,325 cc | Thick skull and bones, primitive features |

Figure 5.11. Heidelberg mandible compared to a modern one.

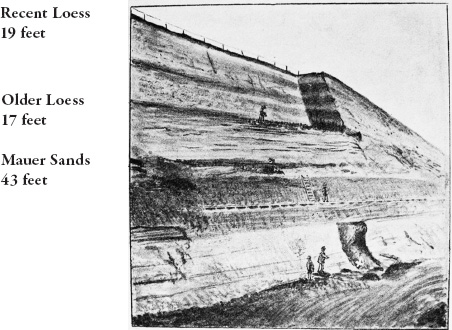

Figure 5.12. Heidelberg site.

Betwixt and between: The pattern remains the same as we go farther back in time—earlier hominids were profound blends as well: H. habilis (found in the same general area as Au) shows foot morphologically quite mixed, the ankle in particular. While he was erect and bipedal, with modern femur and dentition and thin skull, nevertheless his stride was shambling, his arms long, legs short, and hands curved. Although H. habilis’s Ihin genes gave him a notably short stature, his small brain betrays the legacy of Au. Those early men of the African savanna came in a great variety of shapes and sizes, some scholars (noting the great range of types) even doubting that there was a separate species of H. habilis; Mayr, for example, calls H. habilis an Au.

LAST DITCH: DIFFERENTIAL EVOLUTION

We need to take these mixtures more seriously, before tossing them in the “variability” bin or squeezing them into imagined evolutionary sequences or inventing such chimeras as differential, rapid, or mosaic evolution. Differential evolution is the hypothesis that all aspects of an organism do not evolve together, but each at its own rate. African hominids in particular needed this theory; consider Kenya’s Black Skull, for example: “parts of this skull were evolving faster than other parts.”55 How does that grab you? In the case of the australopiths at Olduvai with a foot more modern than the hand, or Au. garhi with relatively mod legs but long (archaic) forearms, supposedly the legs “evolved” quicker than their forearms. And in the case of Laetoli, the feet supposedly evolved before any other body part.

Or take Turkana Boy whose well-preserved skeleton from East Africa (“a mosaic of erectus and sapiens features”) was clearly modern “from the neck down” (the rib cage almost identical to modern man’s), whereas his skull was markedly primitive—with hardly any forehead or chin, and the frontal lobes rather small (880 cc). Now, all this indicated, at least to Brian Fagan, that “different parts of the human body evolved at different rates.”56 Evolved? I don’t think so.57 If face/head/ brain evolved last (as the evolutionists tell us, and as surmised in the case of Turkana Boy), then why did Taung Child of South Africa, an upgraded Au, have a high, round forehead, smooth browridge, delicate cheekbones, and flat (not prognathous) face? Taung, the first Australopithecus africanus ever discovered, was modern from the neck up, just the opposite of Fagan’s differential evolution of Turkana Boy.

Must we resort to ex post facto theories like differential evolution (or modular structure of the genotype) to explain (away) these mosaics, or to explain how the primitive features of Neanderthal compute with his large brain? The Neanderthal skull is more modern than its femur (the same combination found in Swanscombe Man), which is to say, these people were modern from neck up. The same is true for that troublesome Portuguese skeleton, with the perfectly modern chin and teeth that contrast with his thick bones and short legs (of the classic Neanderthal type), reversing the so-called differential evolution of body parts conjured by Fagan for Turkana Boy. And so, at least with the Portuguese find, archaeologists grudgingly conceded “significant interbreeding.” We don’t need differential evolution or any other principle to explain these patent hybrids.

But the theories are piled high and deep. Turkana Boy’s combination of modern body surmounted by a primitive head was so “improbable,” an observer might “wonder if . . . [he] was a visitor from an alternative universe or perhaps the product of some strange genetic experiment.”58 How silly and inane. Java Man, like Turkana Boy, had a primitive skull combined with a fully upright body. Noting the modern femur of this H. erectus, anthropologist Jeffrey Schwartz ventured “our ancestors had become human first from the waist down.”59 But if so, why do Au and H. habilis have humanlike dentition? Ad hoc and inconsistent, a differential rate of evolution is held nonetheless as a “principle,” Turkana Boy nicely confirming that different parts of the body evolved at different rates. Why else would H. erectus appear with modern limbs but primitive jaw, dentition, and cranium? S. J. Gould saw evolution “proceeding at different rates in different structures. . . . This must be true or evolution couldn’t have happened.”60 Well, maybe it didn’t happen.