1

OUR KNOWLEDGE IS SKELETAL

The Truth behind the Bones

O ye of little wisdom; how ye are puffed up in judgment, not knowing the race whence ye sprang!

OAHSPE, BOOK OF APOLLO 5:11

MEET PROTOMAN: ASU

To begin this journey at the beginning may I introduce you to your long-lost ancestor, Asu man?

Naked and unashamed, Asu was the first manlike specimen to walk the Earth, though he might also scamper about on all fours and spend a lot of time in the trees as well. His long arms, curved digits, and upward-facing shoulder joint suited him to arboreal life, while the human angles of his knee joints supported his upright gait. Known as Ardipithecus ramidus to the paleontologist, he was about four feet tall with a biped’s placement of the foramen magnum, meaning neck and head were in line with spine, rather than jutting forward (like apes).

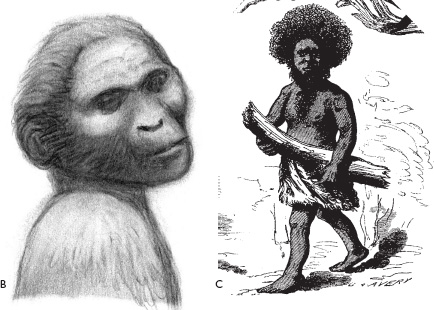

Figure 1.1. Three artists’ impressions of first man. (A) Illustration by Joy Walker. (B) Illustration by Karen Barry. (C) Illustration by Ernst Haeckel.

Yes, Ardi/Asu had a very small brain; he was not a knowing creature, not sapient, not a thinking man and did not use fire or tools. He did not speak and, as one study surmises, was “barely capable of babbling.”1 His diet was of fruit, nuts, seeds, berries, vegetables, roots, and probably bugs. Being the first race of man and in an aboriginal state, he was dun colored and, as the Vedic scriptures of India define the term asu (meaning “animalistic”), “lived and moved in the great phenomena of nature.”*10 He appears again in the Old Testament as Esau, Jacob’s twin, covered with red, shaggy body hair (animal-man). Sumerian Asag may also be a cognate; similar to the Hindu asura, Asag was a demon cursed in a manner not unlike Jacob’s twin Esau.

Concerning this Asu or Adam, the Chukchee (Siberia) have a story of the beginning, when the Creator made the first man—an animal-like, hairy, and four-legged creature with very long and strong arms, great big teeth, and claws. Fearing this man would destroy all living things, the Creator contrived to slow him down a bit, make him less dangerous, so he had him walk upright and shortened his arms: “with Mine Own hands, molded I . . . the arms . . . no longer than to the thighs.”2 Indeed, the first fossil hominid was long armed†11 and powerful—helping him scuttle along on all fours, as the morphology of remains in Africa and Asia attest. These creatures, manlike but rough-hewn, were the very first race of human beings.

Asu man was devoid of the spirit part, just as in Buriat anthropogenesis, where first man was without a soul. “A humanlike being that lacked a soul,”3 he was without the spark of the divine, “like a tree, dwelling in darkness.”‡12 Hence beings of wood as the Mayan Quiche say, were the race preceding their own, for they had no soul, no reason, and did not remember the Creator. In the same vein the first man in Chaldean memory had “lived without rule, after the manner of beasts.”

Yes, like a beast but not an animal, for all the animals (unlike man) have instinct fully supplied. But Asu man was a blank, “the nearest blank of all the living, devoid of sense.”4

The low condition of the first race of man [Asu] is known; but still he was a man and not a monkey, nor any other animal.

JOHN B. NEWBROUGH,

“COMMENTARY ON OAHSPE”

It is my understanding and the premise of this book that Asu man together with Ihin man (the little people, see chapter 2) are the mother lode, the two Ur races of mankind, our true common ancestors. These chapters are about their offspring—the races of man. To some extent, we all have a combination of Asu-Ihin blood. And Australopithecus, the very earliest hybrid, represents the first infusion of Ihin blood into the Asuan race, accounting for “modern” features appearing even in the most archaic of hominids. Table 1.1 summarizes the mixed features of australopith (Au); for Asu was quickly upgraded by those early gene exchanges with the Ihins.

WAS AUSTRALOPITHECUS OUR ANCESTOR?: ARGUMENTS PRO AND CON

Gridlock: Maybe (hopefully) Neaderthal-as-ancestor has been put to rest, but the jury is still out on Australopithecus.

Those Who Argue against Au as Ancestor

Australopithecine specimens from Tanganyika and South Africa were long regarded as off the main evolutionary line. Paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey (son of famed Louis Leakey who shifted the focus of anthropogenesis to the continent of Africa) judged Au to be only a relative of our forebears, one who reached an evolutionary “dead end.” Louis Leakey, like his son, rejected Au as our ancestor, voting instead for Homo habilis, the next higher type with his modern lightness of skull. The elder Leakey, some say, tended to deny that anything (including Peking Man and Neanderthal Man) other than his own (African) finds was ancestral.

| TABLE 1.1. SUITE OF AUSTRALOPITHECINE TRAITS, DISPLAYING MIXED GENES | |

| Primitive (Asu blood) | Manlike (Ihin blood) |

| Heavily muscled body | Vertical foramen magnum (opening in occipital bone of cranium): walker |

| Shoulder joint faces more upward: climber | Broad sacrum and lumbar curve, shortened hip bone |

| Pelvis not modern, funnel-shaped torso | Lower leg and ankle well shaped; “leg and foot bones essentially manlike”*13 |

| Toes curved, long midtoe, heelbone without tubercule | Hands with precision grip; Olduvai hand bones modern |

| Large jutting face and jaw, receding forehead, large brow | Flat, smooth face |

| Large molars and canines; palate archaic | Manlike dentition and enamel; some lack projecting canines |

| Skull vault low, thorax broad at base | Small occipital lobes, thin-walled skull |

| Small brain, less than 600 cc | Prominent frontal lobes |

Anatomist and anthropologist Sir Arthur Keith dismissed Australian anatomist and anthropologist Raymond Dart’s finding of Au. africanus in Taung, South Africa in 1924 as “just another fossil ape.” In his last book Keith (wisely) changed his mind—twenty years after Dart’s finding.

Several authorities rejected Au on the basis of brain size. England’s curmudgeonly zoologist Lord Solly Zuckerman is remembered for his brisk dismissal of australopiths “as having anything at all to do with human evolution.” “They are just bloody apes,” howled Zuckerman, underscoring his lifelong rejection of the australopiths as human ancestors. He didn’t even think they were proper bipeds. And Earnest Hooton, distinguished professor of physical anthropology at Harvard in the first part of the twentieth century, also said “no” to Au as ancestor because of brain size.

Others who did not think Au was on a direct line to humans were archaeologist and anthropologist Brian Fagan and evolutionary zoologist Charles E. Oxnard. Oxnard’s computer analysis in 1975 presumably settled the matter, making Au an extinct ape unconnected with human ancestry: “they must have been upon some side-path.”5 (We’ll look at these “side paths” in a moment.)

More recently, in 2008, paleoanthropologists Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall noted that numerous australopiths came and went over a period of over two million years without significant change in body structure, and therefore, no known Au anticipated human beings.6 Besides, there is no one to fill the one-million-year gap between the australopith Lucy (Au. afarensis) and the first Homo (H. erectus).

Those Who Argue in Support of Au as Ancestor

Although Au were not yet known in Charles Darwin’s time, the father of evolution nonetheless predicted that such a type, once found, would prove to be “our semi-human progenitors” (The Descent of Man). He envisioned “the divergence of the races of man from [such] a common stock.” Raymond Dart, the first to discover any australopithecine (the Taung Child in South Africa, 1924), thought Au was indeed an ancestor, especially considering the position of Taung’s foramen magnum, indicating upright posture.

Among other supporters of Australopithecus as ancestor of man are John Robinson, also of South Africa, who placed all the more gracile Au material within the genus Homo; British-American anthropologist and humanist Ashley Montagu; and Donald Johanson. Johanson, the discoverer of Lucy in 1974, saw Au as the root stock of all future hominids, even though they were “not men”—yet. Still, “you and I have in our teeth and jaws some characteristics that we get almost directly from Lucy,” said Johanson. “We see her, in a sense, as the mother of all humankind. . . . Not everyone has agreed.”7

There have been some fence sitters. Sir Wilfrid E. Le Gros Clark, the great English anatomist and paleontologist of the past century, thought the genus Au as a whole might include our ancestral stock, following Robert Broom, the Scotch–South African physician and internationally renowned vertebrate paleontologist, who thought that Au—based largely on dentition—was a direct ancestor of mankind. In the 1930s, Broom (see figure 8.7) discovered Au in Sterkfontein, South Africa, nicknamed Mrs. Ples (short for Plesianthropus transvaalensis, or near-man from the Transvaal), who was generally accepted as human (or almost human) by the 1950s.

Le Gros Clark (1955) had to agree with Broom, but only provisionally: though Mrs. Ples’s pelvis was modern, the small brain bothered him. Carleton Coon, chairman of the Anthropology Department at the University of Pennsylvania till 1963, also thought Mrs. Ples was a direct ancestor, but rejected the East African australopiths. Paleontologist and geologist G. H. R. von Koenigswald, like Le Gros Clark, was inclined to accept australopiths based on dental form—but felt the geology was too recent and the teeth were actually too big.

THE FIX IS IN

Pursue thy studies, O man, and thou shalt find that supposed exact science is . . . only falsehood compounded and acquiesced. . . . Is the man who finds the vertebra of an insect, not said to be scientific? But he who finds the backbone of a horse, is a vulgar fellow. Another man finds a route over a mountain or through the forest, and he is scientific! Why, a dog can do this.

OAHSPE, BOOK OF KNOWLEDGE 1:36–7

With the origin of man our subject is history, really. We only make it science, clothe it in science, in order to study it. Evolution is a descriptive body of knowledge decked out in hypothetical models, formulas, theories, and best guesses. Though its methods are no doubt empirical, it remains an interpretive field of study. Which is fine. “The ambiguous nature of fossil evidence,” as one critic sees it, “obliges paleoanthropologists to pursue the truth mainly by hypothesis and speculation . . . a science powered by individual ambitions and so susceptible to preconceived beliefs.”8

Mark Isaak, one of the Darwinian fraternity, declares that “[t]he theory of evolution still has essentially unanimous agreement from the people who work it.”9 Does a majority vote among paleontologists add up to the truth? These experts of course are trained professionals, trained to look at the evidence through the Darwinian lens.

This is the simple formula: supposition plus consensus equals fact. “There is something fascinating,” Mark Twain once commented, “about science. One gets such wholesale returns of conjecture out of such a trifling investment of fact.”

The various family trees for man are admittedly provisional, indeed “highly speculative”—in Charles Darwin’s very own words. His expositions are dotted with such terms as feasible, plausible, in principle. As one author went to the trouble of counting, Darwin uses the phrase we may suppose and similar qualifiers more than eight hundred times in his two major books.10 Some have complained of his “constant hedging” and “guile.”11 Darwin’s approach, though certainly rational and databased, is, in its most important aspects, profoundly conjectural. It is still, and will remain, only an opinion that man has a phyletic relationship to the apes—that our species, Homo sapiens sapiens, has evolved from a different, earlier species.

Paleoanthropologists seem to make up for a lack of fossils with an excess of fury, and this must now be the only science in which it is still possible to become famous just by having an opinion.

J. S. JONES, NATURE

There is only one opinion that is shared by all: “The alternative to thinking in evolutionary terms is not to think at all”12 (biologist Sir Peter Medawar). So now evolution is the sacred cow (or is it sacred ape?), and to oppose it is something close to blasphemy, sacrilege. “People made a religion of them [my ideas],” Darwin him-self once fretted.13 Evolution has become (oxymoronically) a secular religion—or call it scientific naturalism. A new orthodoxy for a material age, fundamentalist Darwinism’s central dogma is faith in mutation and transmutation, the process that allows one species to turn into another species (also called speciation). The official creation story of modern humanism, it is our shared origin myth, maintained and glorified by its own scientific priesthood and bully pulpit. Richard Leakey and many others besides have trumpeted evolution as the greatest scientific discovery of all time. And so it has come to pass that of all scientific gospel, evolution is the most sacrosanct. And like all myths, it contains a few truths but is riddled with a mass of errors.

BARE BONES

Today East Africa’s Turkana Boy (Homo erectus or Homo ergaster), discovered in Kenya in 1984, and Lucy (Johanson’s famous Au find) are among the most partially complete skeletons of any pre-Neanderthal hominids—with more than 50 percent of Turkana’s bones recovered and 40 percent of Lucy’s. It is unusual to collect more than a few fragments. Peking Man was named and classified (1927) on the basis of a single tooth! The first human ancestor discovered in the New World was also identified on the basis of a single tooth, which turned out to be a pig’s molar—this “Nebraska man” was actually an extinct wild peccary. As William Howells, in Mankind So Far, cautioned, there is “a great legend . . . men can take a tooth or a small and broken piece of bone . . . and draw a picture of what the whole animal looked like . . . If this were true, the anthropologists would make the FBI look like a troop of Boy Scouts.”

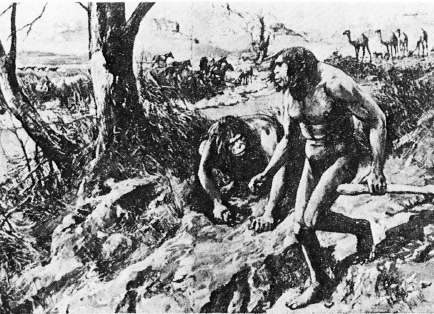

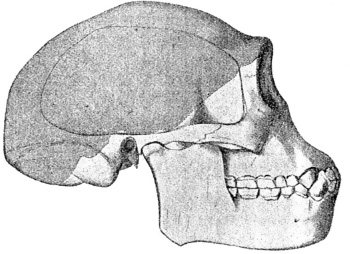

A bone, a femur, a tooth, a mandible, a pinky fragment. All of evolution is a grand and daring reading between the lines of the past. In graphic reconstructions of our ancestors, everything depends on the angle used to put these fragments together. Paleoanthropologists Franz Weidenreich’s and Ian Tattersall’s reconstructions of the same Peking Man look quite different. Teasing out a picture of our ancestor is, to one critic “deceptive evolutionist artistry,”14 while Harvard’s Prof. Hooton in Up from the Ape warned, “To attempt to restore the soft parts is . . . a hazardous undertaking. You can with equal facility model on a Neanderthaloid skull the features of a chimpanzee or the lineaments of a philosopher. . . . Put not your trust in reconstructions. . . . The faces usually being missing . . . leaves room for a good deal of doubt as to details. . . . These alleged restorations of ancient types of man have very little, if any, scientific value.” Without having found any nasal bones of Au. afarensis, the artist’s reconstruction gives a superplatyrrine (flat) nose, very much like our simian “cousins.”

Figure 1.2. Mr. and Mrs. Hesperopithecus (1922), body structure based solely on what turned out to be the molar of an extinct pig!

Neanderthal is often represented with his big toe diverging in apelike fashion, which he never had. Artist Peter Schouten gives Homo floresiensis a gorilla face; after all, his brain, like the ape, was only one-third the size of ours. Though wild-looking, H. floresiensis did not really resemble an ape.

Figure 1.3. Trinil Homo erectus reconstructed. Note that the shaded area indicates the only portion known. As stated in Fossil Man, French paleontologist Marcellin Boule thought such reconstructions “far too hypothetical. . . . It is astonishing to find a great paleontologist like Osborn publishing attempts of this kind.”

DEAD ENDS AND HOMELESS FACTS

Paleoanthropologist Tim White and colleagues thought Ardipithecus ramidus (who corresponds to Asu man) was, if not our direct ancestor, at least a close relative (“sister”) of that ancestor. All such early types (human though they are) that do not quite meet our idea of ancestral are labeled sisters, cousins, collaterals, dead ends, or divergent offshoots from the main line of descent.

So what becomes of human evolution if Neanderthal and Java Man and Au and Ardi are not man’s ancestor but merely an extinct side branch or “failed attempts at becoming human”?15 No, they are not failures, just—as these chapters lay bare—race mixtures. Louis Leakey believed that most lineages have their dead branches, which quietly moved on to extinction. He thought that Au left the Homo line about 6 or 7 mya, and that most of our collected fossil types are simply “aberrant offshoots” from the main stem. American anthropologist Loren Eiseley concurs, deferring to the school of thought that “the true origin of our species is lost in some older pre–Ice Age level and that all the other human fossils represent side lines and blind alleys.”16 Now that we have washed our hands of all these unqualified ancestors, what is left of our family tree? The answer is—a bush (in which the ancestor, nonetheless, still hides).

The complications of interbreeding make it impossible to draw neat branching lines of descent on the family tree.

JOSEPH THORNDIKE JR., MYSTERIES OF THE PAST

And so, with ever more hybrids (rather than ancestors) turning up, paleoanthropologists take care of the problem by calling it diversity or variability and changing the family tree to a bush—but still in an evolutionary context, thoroughly blindsiding the factor of crossbreeding, and all those hybrids. As we have seen, numerous evolutionists concur that Au is off the main evolutionary line to H. sapiens; but as these irrelevant branches continue to multiply, it leaves us with a family tree that is all branches and no trunk! So many also-rans but no winners. No ancestors. Indeed, almost all the nodes or branching points remain unidentified, with big question marks printed at the point when species first appeared.

A tree with no trunk might get knocked down with the first storm; or as the delightful British author Norman Macbeth so aptly put it, “these forms, being ineligible as ancestors, must be moved from the trunk of the tree to the branches. The result is that the tips are well populated while the trunk is shrouded in mystery . . . we see forms that purport to be our cousins, but we have no idea who our common grandparents were.”17

Ian Tattersall of the American Museum of Natural History breezily mentions that the tree is really “quite luxuriantly branching.” Yet in transforming our family tree into a bush, what has really been laid bare is the multiplicity of crossbreedings that make up the human lineage. The molecular revolution (see chapter 6), we might also note, forced us to scotch the tree and go for the bush, since “genes move quite freely between the branches.”18 Can we interpret that to mean intermixtures? If so, we do not need evolution at all to account for the ascent of man! All we need is the blending of types.

First it was an evolutionary “ladder” (linear model), and when that didn’t work, it was changed to a “tree.” But there were problems with tree so they changed it to “bush”; now, as problems arise with bush, they’re changing it to “network”—where will it end?*14

Louis Leakey considered Neanderthal, Java Man, Peking Man, Au, and others as mere evolutionary experiments that ended in extinction. Others say the evolution of a successful animal species involves trial and error and failed experiments. What is this experiment that everyone is bandying about but an empty conceit probably personifying the materialist’s god of nature? “It gives one a feeling of confidence to see nature still busy with experiments,” writes Loren Eiseley,19 while William Jungers, a paleoanthropologist of the State University of Stony Brook, New York, says, “We’re far from the only human experiment.” After all, the apes, except the bipedal ones, were “failed evolutionary experiments.”20 But we are not an experiment and the apes are not a failure. Science engages in experimentation—not nature or the universe. Pray, who is the experimenter?

GOING IN CIRCLES

Evolutionary arguments tend to be jargon happy, model obsessed, and insufferably pedantic: Is it really necessary to say lithic technology instead of stoneworking? If not empty rhetoric, the arguments are couched in forbiddingly technical language and nomenclature (“pompous polysyllabification,” as one critic saw it). There are often surprise changes in the terminology, which forever keeps you off balance in the paleo world. For example, East Africa’s Paranthropus boisei was originally called Zinjanthropus boisei, then changed again to Australopithecus boisei. But it was also known as Olduway Man, Dear Boy (a pet name), and Zinj, as well as Titanohomo mirabilis and FLKI. (One of the Leakeys’ stage names for this creature, Nutcracker Man, had to go: as it turned out, he did not eat nuts after all; he ate grasses and sedges.) Today Olduvai is a safari destination, sporting a stone plinth marking the site of Zinj’s discovery.

Ndangong man of Java, depending upon which book you read, may be called Homo Javanthropus, Homo soloensis, Homo sapiens soloensis, Homo primigenius asiaticus, Wadjak Man, Homo sapiens, or Homo neanderthalensis soloensis. Or try researching Swanscombe Man. He is one and the same as Homo sapiens protosapiens, Homo marstoni, Homo swanscombensis, and Homo sapiens steinheimensis. In my own research, it took months before realizing Homo rhodesiensis was the same fellow as Broken Hill Man, Kabwe Man, and Rhodesian Man (and it doesn’t help that Rhodesia was changed to Zimbabwe).

Embarrassing gaps and jumps in the record are called “systemic macromutations” (swiftly turning a liability into an asset). I am certainly not the first to point out the circularity of Darwinism’s basic premises. Example: “The process of human evolution [is] a series of adaptive radiations . . . the basis for each radiation was a mixture of adaptations to local conditions and geographic isolation.”21 Translation: species evolved by evolving. The buzz phrase adaptive radiation is itself circular, the concept founded on nothing more than the assumption of evolution itself. “Adaptive radiation strictly speaking refers to more or less simultaneous divergence of numerous lines from much the same adaptive type into different, also diverging adaptive zones . . . a rise in the rate of appearance of new species and a concurrent increase in ecological and phenotypic diversity.”22 Say what? Do these words mean anything at all? Bipedal locomotion (which I discuss in chapter 9) is given as another (meaningless) instance of adaptive radiation. The Cambrian explosion is another. Every big set of changes is an adapative radiation. Why? Because the experts say so.

Circular logic underlies the extremely important business of fossil dating: The number of mutations, they say, gives us age; yet age tells us the number of mutations! This molecular clock (discussed in chapter 6) is said to measure the time since humans and chimps last shared a common ancestor, assuming of course they did indeed share a common ancestor. But the word homology does just that: homologs are defined as protein sequences that diverged from a common ancestor. Correspondence of structure (homology) then indicates a common ancestor. And this is circular: evolutionary descent supposedly explains similar organs in different animals, and these similar organs are then cited as proof of evolution. “Homologous organs provide evidence of [descent] from a common ancestor.”23 In other words, comparable organs, say hand and paw, can be traced to a common ancestor. Sheer supposition! (Things could be alike for a different reason—just as the tuna, porpoise, and mako shark look much alike though of vastly different ancestry—but more on homology in chapter 8.)

Dating follows another loop of circularity: if a hominid is dated before the Mindel interglacial period, call it H. erectus; if it’s H. erectus, date it before the Mindel.24 And how’s this for tautology?: “Small changes operating by degrees were the main instrument of change.”25 In other words: change was caused by changes. And how does evolution explain change? By natural selection (chapter 9). What is natural selection? That which produces change!

Fitness, as genetics defines it, is effectiveness in breeding. But there is a problem here because today, the least “fit” (in Darwin’s thinking) reproduce the most, that is, the poorest, most disadvantaged people in the world have the highest birth rate. American sociologist Elmer Pendell (political correctness be damned) has recently opined that the decline of our institutions and way of life is caused by the higher reproductive rates of those who should reproduce least. It has also been pointed out that in time of war, it is the most fit who perish.

One critic, taking a closer look, finds circularity in the competitive exclusion argument, which assumes only one group can inhabit or dominate a niche: “Count the number of species in a given habitat to determine the number of [ecological] niches the habitat contains, and lo and behold, there is one species for every niche.”26 In Origin, Darwin informed us that “variations will cause the slight alterations”; in other words, the cause of variations are variations.

One writer assures us that H. erectus “clearly migrated out of Africa because that was where people learned how to hunt large animals.”27 Logic? One team found (from DNA) that the Neanderthal population must have at one point shrunk to as low as just a few thousand individuals. Sure, they eventually went extinct! One critic has recommended that evolutionists “take a course in logic.”

Strange and presumptive logic is seen in assertions such as Neanderthal had to be a big game hunter “for their bodies demanded” many calories in the cold.28 But he was not a big game hunter and probably not cold, either (see chapter 9). Along the same lines, H. erectus had to have fire, otherwise he could not have come out of Africa (as theory requires). Neither of which is the case.

Here we note that evolutionists keep telling us that things arose because they were needed. I wonder if it’s that simple. This is Darwin country’s particular metaphysic. But do things really happen because they’re needed? Did pale skin and freckles come about “under pressure in northern latitudes to evolve fair skin to let in more sunlight for the manufacture of vitamin D”?29 (a problem we will take up later on). Most insidiously, evolution itself “needs” deep time (long dating) for things to evolve (to which question chapter 6 is devoted).

The would-be syllogism is: Species lacks (whatever); species needs (whatever); therefore, species acquires (whatever). Ashley Montagu, for instance, accounts for the increase in human brain size in this manner: “The brain would have been enlarged because of the necessity [e.a.] of a large enough warehouse in which to store the required information.”30

That human knowledge or language allowed us to advance as a species is a bit like saying that we have legs allowed us to walk. In this connection science writer James Shreeve finds Jared Diamond’s logic “dizzyingly circular” for he, Diamond, defines the Upper Paleolithic by cultural invention, which depends on language as the spark or prime mover behind the creative explosion at that time. How do we know, asks Shreeve; the answer—“because the Upper Paleolithic is defined by invention.” Diamond’s argument betrays a “total lack of evidence for the crossing of the language Rubicon at the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic.”31

All told, modern-day evolution has perfected the art of assuming what you wish to prove, circularity is deeply embedded in the heart of this “science.” We search in vain for the causation, the forces exerted to make man evolve from a lesser to a more sapient state, for H. sapiens did not evolve from anything. H. erectus did not evolve from anything. Neanderthal did not evolve from anything. But each came about through the process of crossbreeding.

HOW THE MIGHTY ARE FALLEN

Evolution makes better murderers.

WALTER MOSLEY, WHEN THE THRILL IS GONE

One fly in the evolutionary ointment is stasis, meaning no change over time. We see this stasis, for example, in Mayan art and architecture, which show “no development with the passage of time, ending up exactly as it began.”32 In the Old World, tools remain crude between the time of Zinj (Au) and Peking man (H. erectus)—a long stretch with no indication that man was evolving or progressing.

The history of the human race . . . gives no countenance to any doctrine of universal and general progress . . . but sustains rather a doctrine of predominant natural tendencies to degeneration. . . . There is no invariable law of progress. . . . As a matter of fact, degeneration and disintegration seem as likely to take place as real progress and advancement.

GEORGE FREDERICK WRIGHT,

ORIGIN AND ANTIQUITY OF MAN

Indeed a certain trend toward devolution is noted in many different traditions, which mutually speak of a lost golden age, a lost utopia, having fallen to barbarism; and this is where retrobreeding shows its face. “In times past the same countries were inhabited by a higher race.”33 In Malaysia “a white race relapsed into barbarism” in the jungle interior.34 Protohistorians of every stripe can attest to such relapses, as in the Pacific, in places such as Ponape and Easter Island, where a dramatic regression of culture has taken place.

In some nameless, distant past mankind must have ascended a long way up the ladder of civilization, only to relapse into chaos and barbarism.

PETER KOLOSIMO, TIMELESS EARTH

Future studies of the protohistorical world might well reveal that retrobreeding, followed by war, destroyed both antidiluvian and postdiluvian civilizations, “and war spread around about the whole earth” (ca 70 kya).35 Much later, just before the flood, men were “descending in breed and blood . . . and they dwelt after the manner of four-footed beasts.”36 Then, after the flood, these histories follow with Ihuan internecine wars (ca 20 kya).37 Later still, around 10 kya, “the Parsieans [high culture] were tempted by the Druks [barbarians], and fell from their high estate, and they became cannibals.”38

Hopi history tells of the third age*15 with a mighty civilization, full of big cities; Hopi artist and storyteller White Bear spoke of big cities, nations, and civilizations that once were, but war and other evils destroyed them. Likewise does archaeology reveal extensive trade networks once centered on the Mississippi Valley mound culture. Canadian Indians knew of “shining cities” before “the demons returned”; there, where once splendid cities stood, “there is nothing but ruins now.”39

All was lost. The complexity and beauty of the earlier layers at Guatemala’s Tikal was puzzling to archaeologists; things did not get simpler, less elaborate, the deeper they dug, quite the reverse. By the time of the Spanish conquest, Mayan civilization was already run down. And the same befell the great societies of the Old World:

The palaces and houses with their goodly apartments fall into ruin. . . . Serpents hiss and glide amid broken columns.

KALIDASA, SANSKRIT POET, 350–420 CE

Speaking of India, the erudite British archaeologist Godfrey Higgins observed that the science and learning of the Hindus “instead of being improved, has greatly declined from what it appears to have been in the remote ages of their history.”40 Here in India and Pakistan, the lowest strata at Mohenjo Daro, an ancient city of the Indus Valley civilization, produced implements of higher quality and jewelry of greater refinement than in the upper layers. This mysterious civilization has been compared to the equally mysterious Easter Island, where the oldest cultural level is again the most advanced: the statues of the second period have a degenerate style compared to the earlier ones; just as Egypt’s first pyramids were indeed their finest. The masterpieces of Mesolithic art (Cro-Magnon), possibly the oldest art in the world, were never matched in the later Neolithic. Rather than straight-line evolution, we are faced with cycles, the curve of civilization as a waxing and waning thing.*16 In chapter 3, I come back to these relapses of the Ihuan race.

In case after case, the oldest stone remains are the grandest and most perfectly executed; what followed later are crude imitations.

RICHARD HEINBERG,

MEMORIES AND VISIONS OF PARADISE

“The tribes of men . . . prospered for a long season. Then darkness came upon them, millions returning to a state of savagery.”41 In Mysteries from Forgotten Worlds Charles Berlitz noted “the retrograde tendency of American and numerous other ancient cultures . . . as one goes farther back in time, one finds more advanced cultural patterns in preceding eras.”42

Evolutionists seem to be entirely indifferent to the now substantial body of literature on high culture prior to the Magdalenian. Nevertheless, independent studies of the deep past reveal a golden age superseded by decline and savagery. If nothing else, the repeated fall from high civilization puts the lie to steady evolutionary progress from primitive to advanced.

Her people build up cities and nations for a season . . . but soon they are overflooded by [darkness], and the mortals devour one another as beasts of prey. . . . Their knowledge is dissipated by the dread hand of war . . . and lo, her people are cannibals again. . . . As oft as they are raised up in light, so are they again cast down in darkness.

OAHSPE, SYNOPSIS OF SIXTEEN CYCLES 3:6–10

I wonder why evolutionists, so big on competition (see below), deny the obvious cannibalism of prior ages? Why did Cro-Magnon disappear ca 12 kya? The questions are related, for the Ihuans (Cro-Magnon), inhabiting the wilderness, “ate the flesh of both man and beast.”43 As we go on, we will encounter other instances of retrogression in the Ihuan–Cro-Magnon race, which turns up in the record with a considerable sampling of archaic features (low skull, long arms, large orbits), indicating that this perfectly AMH race retrobred with Neanderthaloids, thereby descending lower and lower.

Just as the Paleolithic was coming to a close, ca 12 kya, “tribes of Druks and cannibals covered the earth over”—which corroborates ufologist/prehistorian Brinsley Le Poer Trench’s observation of cannibalism in Egypt around the time of Osiris. It was probably on that same horizon that the Greeks had their Polyphemus, a notorious cannibal. The cave of Fontbregoua in southeast France contains bones bearing cut marks, dated to around the same time, attesting to the presence of “savages and cannibals all over these great lands; enemies slain in battle [were] cut up for the cooking vessel.”44

But man eating was nothing new. Raymond Dart found evidence of cannibalism among Au, almost our earliest progenitors. In South Africa charred bones of human victims were found at Klasies, as well as at Bodo (Ethiopia). “In sights ranging from South Africa to Croatia to the U.S. Southeast, similar evidence indicates that cannibalism may long have been part of the human heritage.”45

Cannibalistic giants in the Americas may have been large Druks—the red-headed goliaths who terrorized the Indians of Nevada until fairly recent time. Sarah Winnemuca, a Paiute, wrote about a tribe of barbarians that once waylaid her people, and killed and ate them. The 1,000-year-old Anasazi site in the Southwest did indeed produce bones with cut marks. We’ll come back to these huge and troublesome Druks.

Just as Judeo-Christian tradition has the sins of the giant Nephilim bringing the deluge upon the world, Greek, Arabian, Roman, and Peruvian traditions likewise suggest that troublesome giants were the cause of the flood: “[T]he land of Whaga (Pan) was beyond redemption. . . . They have peopled the earth with darkness . . . and cannibals.”46

Archaeologists sifting through the remains of Druks and Neanderthals have come across unmistakable evidence of man eating: for example, in Spain at Atapuerca’s Gran Dolina and Sidron caves (dated 43 kya), where cut marks on bones indicate that the edible marrow was sucked out from defleshed, charred, and splintered bones, and at Germany’s Ehringsdorf site as well as at Steinheim, where skulls show heavy blows to the frontal bones. In Europe, Krapina (Yugoslavia) and Monte Circeo (Italy) are two important Neanderthal sites with the telltale remains of cannibal feasts: bodies and bones smashed open to get at marrow and brains.

But for some unknown reason, archaeologists are squeamish about announcing these incontrovertible finds, despite the work of Earnest Hooton, Franz Weidenreich, Robert Braidwood, and other top dog anthropologists, who found cannibalism at Zhoukoutien, China—judging from heavy blows on the Sinanthropus pate. Though this Peking Man was a headhunter who ate brains, Ashley Montagu stated: “It has been asserted that Peking man was a cannibal. . . . This is possible but unproven. . . . Except in aberrant cases, it is highly unlikely that man has ever resorted to eating his own kind except in extremis or for ritual purposes.”47 British archaeologist Paul Bahn interprets the Krapina and Monte Circeo finds as the result of a tragic roof fall, or perhaps a landslide, or the use of dynamite during excavation. And if that doesn’t fly, the Fontbregoua (France) and Krapina bones are understood in a ritual context: the defleshing of bones taken “as a stage in a mortuary practice.” Bahn also discredits the Monte Circeo evidence, despite the presence of a chisel-like object used to scoop out the brains, every skull of which shows fractures at the same spot around the right temple. This, he concludes nonetheless, must have been a hyena den, the tooth marks consistent with those of hyena. Cannibalism, he says, was “rare or non-existent,” and his interpretation has “demolished the myth.”48

But headhunters and cannibals are well known even from the recent past. The Aztecs, not too long ago, practiced human sacrifice and cannibalism, and when the Portuguese first got to South America, some of the local natives were cannibals, including the Yaghan and “Indios bravos” of Brazil’s Matto Grosso. In Borneo, the Dyak’s long-house still displays the skulls of people whose brains they ate, the practice also known in Indonesia and once widespread in Sundaland: Ngandong skulls of Java were smashed at the base like the Dyak ones. Until the eighteenth century the Ebu Gogo on Flores ate human meat. Until recently in New Guinea, too, tribesman ate brains of their enemies, the practice prohibited eventually by the colonial powers (in the 1880s). Other examples of cannibalism in modern times have been documented among Fijians and other Melanesian tribes. In the seventeenth and eighteenth century Easter Islanders were found to have resorted to cannibalism and the Tongans in the South Pacific were also man-eaters. Even in today’s Africa are the fierce cannibal people of the Congo, the Fang. Uganda’s atrocities and war crimes of very recent days include rape, mutilations, and cannibalism. During India’s drought and Skull Famine (1792) there was widespread cannibalism. Man of both the past and present was not above feasting on his fellow man.

A PAEAN TO MOTHER NATURE

When men first cottoned to the idea of evolution (On the Origin of Species, 1859), the world was good and ready for it. The universities were still strongly beholden to the Church of England; natural science, in other words, was still in thrall to the tenets of religious gospel. Science needed to be secularized. Its time had come. It was a world that was reaching beyond the straitjacket of theology and past-thought, that wanted to know the unadorned truth, the facts of man’s beginnings, free of dogma and doctrines passed down by scriptural fiat. It was time for old fallacies to bend with the winds of change.

The Darwinian revolution, toppling old and fixed ideas, was inevitable, refreshing, and necessary. It served its purpose. But having freed itself from the shackles of theology, the scientific mind proceeded to embrace the opposite fallacy, the materialist/reductionist dictum. No sooner was anthropogenesis wrested from its biblical confines and made an article of science, than Darwinism itself became the new authority—the new gospel, the new dogma.

Victorian society, in the midst of the grinding Industrial Revolution, was having a love affair with the phenomena of nature, and Darwinism was the ultimate paean to nature per se, Mother Nature’s power. The progressive Victorian mind was also ready to jettison the “fixity” of species (immutability), as one more token of ancient dogma. Evolution appealed also to the entrepreneurial class, the educated, and the rising bourgeoisie, somehow affirming their sense of rank and higher worth, their qualification as the “fittest.” Darwin’s transmutation of species, moreover, only reinforced the optimistic nineteenth-century belief in progress, but more than just progress, it vindicated the upper-class white Europeans “who were taking over the world.”49

It is a curious thing that modern thinking has struck down almost every Victorian theory—except evolution. It’s staying power depends on this: Without it, science would have to admit it doesn’t know how human beings got here, a naked confession of ignorance. With atheism (or humanism) the predominant “religion” of today’s intelligentsia, the Weltanschauung of this secular age, the only real alternative to evolution—the divine hand, the work of the great unknown—is not acceptable. Many scientists are agnostic or possessed of split mind (forever undecided), a kind of cognitive dissonance.

BLUEPRINT FOR A COMPETITIVE AGE

Evolution, in our own age of profit, has granted us a subliminal charter for exploitation, privilege, and discrimination. The standard word for a species’ use of the environment (the ecological niche) is exploit. Animals and men are routinely described as “colonizing” their habitats (even if they’ve always been there, see chapter 11).

A foundation myth, to give a quick definition, is a story or legend that legitimizes a social custom or value system. The Darwinian struggle for existence, conceived as the war of nature, helps us to understand and justify our own warlike age. Richard Dawkins, Darwin’s principal sharpshooter today, uses the arms race as an analogy for survival of the fittest and, by inference, makes it quite normal for one race to dominate another. In a personal letter, Darwin once wrote that the more civilized races have “beaten [the others] in the struggle for existence. Looking to the world at no very distant date, what an endless number of the lower races will have been eliminated by the higher civilized races throughout the world.”50 Regarding this outlook, I am reminded of an Oahspen verse: “Now, behold, I have left savages at your door, and ye raise them not up, but destroy them. Showing you, that even your wisest and most learned have no power in resurrection [upliftment].”51

Capitalists have long used social Darwinism to justify unfettered market competition, on the plea that competition is crucial for progress and for weeding out those who don’t keep up. Progress, in such a scheme, is only possible by eliminating imperfections from humanity—best accomplished through competition. The complete title of Darwin’s famous book was The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or The Preservation of Favored Races in the Struggle for Life. Buttressed by such ideas of the favored or fittest nations, expansionist policies have only thrived on survival of the fittest and the belief in Manifest Destiny, all cloaked in the garment of science and enlightenment. “In prim Victorian England,” noted Jeffrey Goodman in The Genesis Mystery, “Darwin’s thoughts about dark-skinned natives prevailed, providing a footing for racism and . . . imperialism.”52 This idea of survival of the fittest, of the favored, which nicely lends itself to a master race theory, finds Darwin, in chapter 2 of The Descent of Man, accounting for animal and plant migrations according to the “dominating power” of those favored species in a “higher state of perfection.” Well, no wonder: Darwin’s father always told him that “the race is for the strong.”

Not a few have taken exception to the competition model, which seems to rationalize one group (the fittest) monopolizing the niche. American politician William Jennings Bryan, in the 1920s, believed that the Darwinian law of competition was just the sort of ideology that allowed such evils as robber baron capitalism and German militarism. Hitler, a convinced Darwinist, leaned on the evolutionary biology of Ernst Haeckel. Haeckel, Germany’s best-known Darwinian propagandist, judged the different human races to be as distinct from one another as different animal species, with the Teutonic/Nordic people, of course, as the pinnacle of evolution. Consider the devastating results of this racial-state idea and predatory nationalism.

A recent writer, chronicling the words of a Holocaust survivor, quotes him as stating: “If we present a man with a concept of man which is not true, we may well corrupt him. When we present man as . . . a mind-machine . . . as a pawn of drives and reactions . . . we feed the nihilism to which modern man is prone. . . . The gas chambers of Auschwitz were the ultimate consequence of the theory that man is nothing but the product of heredity and environment.” The chronicler then makes mention of “the famous German Darwinist Ernst Haeckel . . . [who] blasted Christianity for advancing an anthropocentric . . . view of humanity. . . . Today the atheistic Darwinian biologist Richard Dawkins argues that, based on the Darwinian understanding of human origins, we need to desanctify human life, divesting ourselves of any notion that humans are created in the image of God and thus uniquely valuable.”53

The central mechanism of evolution, natural selection, always seems to entail one group holding the advantage over another. In evolutionary thinking, someone always has the advantage. It is obvious, at least to Ian Tattersall, why H. sapiens, “intolerant of competition . . . and able to do something about it,” came to be the only human species on Earth. When they arrived in Europe, supposedly from Africa, and found Neanderthals, within ten thousand short years, the Neanderthals were gone, presumably as a result of failing in competition with the newcomers. Known as the replacement model, this idea of conquest or subjugation or even genocide is just one spinoff of the misguided and self-condoning theory of competition. It is likewise assumed that Homo habilis went extinct because “he could no longer compete.”54 In some circles, australopiths are regarded as “failed” humans. We often find this word failure (as well as success) in the literature: “The successful development of one group spells doom for another,” said C. Loring Brace. But even if Darwin and his followers were right about competition, so what? It does not follow that a different species resulted from it, and it cannot be used successfully to explain species disappearance or extinction. The idea that poorer species are replaced by better ones remains unproven. Through the evolutionary lens, even extinction is a failure (failure to adapt), which is not only “impossible to prove”55 but actually circular—extinction is the failure to survive!

With evolutionary patois set in the competitive mode, technology, it is argued, gave early man “an astonishing advantage” over other hominids, Tim White remarking that man now had “the ability to exploit a broader range of habitats, eventually enabling our ancestors to leave Africa and colonize most of the globe . . . [becoming] the ultimate victor [e.a.].”56

Using survival alone (self-preservation or even group preservation) as the measure of success sends the wrong message to students of life. With no morality or ethics or quality in the equation, life is sterile, stripped of purpose and meaning, trapped in the darkness of matter. Just survive, as if the end (survival) justifies the means, which are selfishness and competition. The implication is that aggression, outdoing the rival, is not only inherent but also the key to success.

NOT A DOG-EAT-DOG WORLD

Overlooked in all this is nature’s give and take, her symbiotic side—two species engaging in intimate, mutually beneficial behavior. Plants, for example, get phosphorus and other nutrients from fungi, which settle on their roots; while the fungi get carbohydrates from the plant. Plovers pick leeches from crocodile’s teeth, offering dental hygiene in return for food; just as the whale shark waits calmly as pilot fish swim in and out of its mouth—cleaning its teeth. Bees, while collecting nectar, pollinate dozens of species of flowers. “Symbiosis . . . pops up so frequently that it is safe to say it’s the rule, not the exception. . . . More than 90% of plant species are thought to engage in symbiotic couplings.”57 Neither could any of us humans exist without the bacteria that live in our gut, digesting food and producing vitamins. Evolutionists call all this coadaptation, but are at a loss to explain how this evolved in stages. How could two different species evolve separately, yet depend on each other in such intricate ways for survival?

As Richard Milton has pointed out, in Shattering the Myths of Darwinism, “the overwhelming majority of creatures do not fight, do not kill for food and do not compete aggressively for space.” Food sharing, it is widely believed, is what made us human. We hear that the last common ancestor of hominids and African apes was characterized by relatively little aggression. We have not found much evidence of primate-versus-primate strife. Chimps, our “nearest” cousins, are quite peaceful; most apes are vegetarians. Altruism, it is further revealed, even between different species, is not uncommon. Dominance nonetheless remains a central theme of Darwinian evolution. Has it endured simply as a charter for Western opportunism and unrelenting hegemony over the Third World? For ours is a philosophy of winners and losers—what a dark view of man, making self-preservation at the cost of others the supreme law. Symbiosis/cooperation is called by Darwinists the problem of altruism! But it is not a problem.

Within the same species, powerful . . . safeguards prevent serious fighting. . . . These inhibitory mechanisms . . . are as powerful in most animals as the drives of hunger, sex or fear. . . . The defense of territory is assured nearly always without bloodshed.

ARTHUR KOESTLER, THE GHOST IN THE MACHINE

Our ancestors were strongly cooperative creatures. . . . Social cooperation [w]as the key factor in the successful evolution of Homo sapiens. . . . We are a cooperative rather than an aggressive animal.

RICHARD LEAKEY AND ROGER LEWIN, ORIGINS

We will not be a “successful” species until we achieve harmony, trust, understanding, fellowship, self-discipline, and reciprocity, which are the keys to enlightenment. Science without a moral rudder, without the guidance of humane principles or the consideration of goodness itself, will run riot on the future of mankind. If man is to be a successful species, he will learn to overcome his competitive bent, seeking unity and common cause all the days of his life.