South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu proved to be a constant thorn in the side of American efforts throughout 1971–72 to negotiate a peace settlement and only relented when backed into a corner by Nixon and Kissinger.

As the American war in Vietnam dragged into its eighth year, U.S. battlefield deaths had fallen to ten per week (down from an average of 280 per week in 1968), troop levels were slated to fall to below 65,000, and the burden of fighting had shifted to the Saigon regime thanks to the Vietnamization program.1 Americans were tired of the war, a war that was increasingly being pushed to the backburner of their concern, yet it was no closer to being resolved.

With peace talks deadlocked in Paris, both sides sought to tactfully bolster their negotiating position on the battlefield. For Washington this meant continuing to militarily strengthen the capability of President Thieu’s government to survive on its own, while also threatening retaliation should Hanoi escalate its attacks. For Hanoi this meant accelerating its buildup of forces and supplies in Cambodia, Laos, and the southern panhandle of North Vietnam in preparation for going over on to the offensive once the time was right—the South Vietnamese still too weak to stop them and the Americans too ill-disposed to return to the battlefield. By all calculations the Vietnamese zodiac calendar’s Year of the Rat that began on February 15, 1972 was shaping up as a time of decision.

Despite the lackluster pace of peace talks amid the seeming intransigence of the North Vietnamese, President Nixon was far from ready to throw in the towel. Yes, the administration wanted out of Vietnam as it promised the American people. Yes, the American public was tired of the war and ready to move on. And yes, the Congress was increasingly reluctant to fund what seemed like an open-ended commitment to the Saigon government, which appeared to be as weak and feeble as ever despite hundreds of billions of dollars in U.S. military and economic assistance. Nonetheless, for Nixon and Kissinger the price of failing to obtain “peace with honor” in Southeast Asia was too high a political cost to incur and as long as they were willing to prevent the North from gaining a victory on the battlefield there was hope of success at the negotiating table. It was a supreme test of wills. It was also a dangerous gamble.

South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu proved to be a constant thorn in the side of American efforts throughout 1971–72 to negotiate a peace settlement and only relented when backed into a corner by Nixon and Kissinger.

The Nixon White House was willing to take this risk, because it believed the future credibility of American foreign policy and global leadership was at stake. Any resolution of the conflict in Vietnam that damaged or negatively affected American standing in the world was unacceptable. Nixon and Kissinger saw themselves as operating on a global stage beyond Southeast Asia. Détente with the Soviet Union, arms control, revamping the Sino-American relationship, and stemming conflict in the Middle East were the new priorities for the Nixon White House. Vietnam had been President Lyndon Johnson’s problem, but it was not going to be theirs. Cold, hard political calculus revealed that American military disengagement from Vietnam after 1968 was the only option left; it was only a question of the manner and the timing.

The role of international diplomacy and American grand strategy was also seen as critical in Washington’s ability to pressure Hanoi into make concessions. By leveraging the prospect of improving relations with the Moscow and Beijing, the Nixon administration sought to isolate North Vietnam. The loss of Soviet or Chinese support—or even the perception of pending loss—might be just enough to force Hanoi’s hand at the peace talks. Moreover, a closer relationship with either benefactor would likely reduce the chances of a strident reaction from Moscow or Beijing should the United States choose to unleash massive military force directly against the North Vietnamese. While high-profile American summit diplomacy failed to break the negotiation logjam in early 1972, the message was clearly not lost on Hanoi: old alliances are vulnerable, the world is changing.

In the meantime, fearful that Hanoi would increasingly seek to take advantage of the American troop drawdown to shift the balance on the battlefield in the South, the administration was forced to rely on tailored military force to affirm its resolve and burnish the political position of the Thieu government. By late 1971, however, Washington had become nearly entirely dependent on air power to signal its displeasure with Hanoi and to counter provocative North Vietnamese military activity outside of South Vietnam. This U.S. air effort took two primary approaches: interdiction of the Ho Chi Minh Trail through intensive bombing and the launching of “protective reaction strikes” into North Vietnam.

President Nixon sought to honor his 1968 election pledge to draw down U.S. ground combat forces in South Vietnam, despite fears by many of his military commanders that Hanoi would seize the opportunity to pursue victory over Saigon on the battlefield.

Stopping, or at least slowing, the steady stream of men and matériel infiltrating into South Vietnam from the North had long been an essential element of American counterinsurgency strategy from day one. Accordingly, Washington committed extensive manpower, equipment, and technology from 1965 onward in an attempt to interdict the Ho Chi Minh Trail. This proved to be a Herculean task. With its vast array of jungle trails, improvised roads, makeshift bridges, and waystations that ran through the southern Laotian panhandle and into eastern Cambodia, it was a next to impossible assignment to accomplish. This was not for want of trying. Vast swaths of the Laotian jungle were under constant aerial reconnaissance and more than 20,000 highly sophisticated seismic and acoustic sensors were eventually seeded along infiltration routes.2 As part of Operation Commando Hunt, U.S. aircraft, including heavy B-52 bombers, subjected key road junctions, mountain passes, bridges, and hidden supply depots and logistics support facilities to relentless day and night bombing. Meanwhile, patrolling AC-130 and AC-119 aircraft along with helicopter gunships sought out vehicular traffic for destruction. The missions were not without their risks, as beefed-up North Vietnamese air defenses, including the first confirmed presence of SA-2 surface-to-air missiles in April 1971, took a rising toll on American aircraft. By the end of the year it was estimated that the North Vietnamese had some 550 anti-aircraft guns deployed in Laos.3 A total of 26 Air Force and Navy aircraft were lost in 1971; 24 pilots and crewmen were killed and another six taken prisoner.4 In addition, the effort was estimated to be costing the United States about $2 billion a year.5

Unfortunately, the results were not always commensurate with the effort, which provoked an ongoing debate. There were sharp disagreements as to Commando Hunt’s effectiveness. The Air Force claimed the operation was destroying about 60 percent of the supplies transiting southern Laos, while the CIA estimated the figure at only 20–25 percent.6 Moreover, many in the intelligence community believed that given the relatively low logistics requirements to maintain enemy forces in the field, any reduced flow of supplies through Laos was likely to have little impact on the level of enemy activity in the South. The Joint Chiefs of Staff countered this by saying that any “hampering of the flow of men and supplies … greatly restricted enemy initiatives and in some cases forced him to forego planned operations.”7 MACV even went so far as to say that the interdiction effort “took a serious toll of Communist trucks and supplies, thereby preventing any generally sustained ground activity by the enemy in 1971.”8 Like many contentious issues this one would not be resolved, but rather be over taken by events in the early months of 1972.

The other pillar of American air power was the use of “protective reaction strikes.” Originally intended as retaliation for Hanoi’s harassing attacks against U.S. reconnaissance aircraft overflying North Vietnam following the 1968 bombing halt, these reactive strikes increasingly came to be seen by the Nixon administration as an important tool in pressuring Hanoi both diplomatically and militarily. In point of fact, with the declining American military presence in Southeast Asia, Washington had few options left for flexing its muscles.

The result, however, was an escalating spiral of reprisals by both sides. Hanoi, unwilling to let this aggression go unchallenged, shifted stronger air defenses—including radar-controlled 85-mm anti-aircraft guns and SA-2 batteries—southward toward the demilitarized zone (DMZ) and closer to the Laotian border. By early 1971 American and allied aircraft operating over Laos and south of the DMZ were subject to mounting air defense fire. This elicited several large-scale protective reactive strikes by Air Force and Navy aircraft in February and March, involving more than 300 strike sorties and flying missions deep into North Vietnamese territory.9 Vietnamese People’s Air Force (VPAF) fighter aircraft also began penetrating Lao airspace in April 1971, posing a new threat to U.S. aircraft operating there. Photo reconnaissance also showed refurbishment of several older VPAF airfields south of the 19th parallel, including at Quang Lang adjacent to the border with Laos.

By the early 1970s the civil war in Laos between the Western-supported Royal Laotian forces and the North Vietnamese-supported Pathet Lao communist insurgents was entering its third decade. And since the mid-1960s it had become a venue for a de facto proxy war between Washington and Hanoi, one that would serve as a major theater of U.S. air operations right up until the very end of the America’s Vietnam involvement.

Operation Barrel Roll was the first U.S. air interdiction operation and grew out of a plea by the Royal Lao government for assistance in slowing the flow of supply to Pathet Lao forces from North Vietnam. In December 1964, President Lyndon Johnson secretly authorized limited American airstrikes in the northeast border area of Laos and North Vietnam. The Air Force and Navy, operating from bases in Thailand, South Vietnam, and the Gulf of Tonkin, employed a wide variety of strike aircraft, including B-52 bombers, to attack enemy supply depots, bridges, and transportation routes. In addition, American air power was used periodically to stem Pathet Lao offensives. Although the bombing had only marginal military impact on the Laotian civil war, it provided a strong psychological boost to the Royal Lao government. Barrel Roll finally came to an end in February 1973 when the United States completed its withdrawal from Vietnam.

By the end of 1964 the Laotian panhandle, which contained the Ho Chi Minh Trail and other North Vietnamese infiltration routes, had become part of a major conduit into South Vietnam. To counter this flow of men and supply Johnson authorized Operation Steel Tiger in April 1965. By mid-1965 the Americans were flying 1,000 sorties per month as part of the interdiction effort and by 1967 that number had increased to more than 3,000, over half of which were large B-52 strikes. Air Force AC-130 and AC-119 gunships were also used extensively with devastating effect against truck and troop convoys. A subsidiary operation, Tiger Hound, covered the far southern Laotian panhandle adjacent to the five northern provinces of South Vietnam as part of General William Westmoreland’s extended battlefield and fell under his control.

In 1968 the air interdiction effort against the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos was consolidated into a single new effort, Operation Commando Hunt, which lasted until January 1973. The difficult jungle terrain, North Vietnamese concealment techniques, and the tireless repair efforts of hundreds of thousands of laborers often limited the effectiveness of the bombing. Moreover, despite claiming to have destroyed tens of thousands of trucks, huge quantities of ammunition and supplies, and killed or wounded a large number of enemy troops, the American effort had only a marginal impact on the North’s ability to prosecute the war in the South or limit its ability to mount large-scale offensives.

General John Lavelle as commander of the Seventh Air Force since August 1971 sought to pursue an aggressive retaliatory air strategy against the North, but found himself caught up in a political whirlwind that cost him his job and career. (Photo U.S. Air Force)

As the year progressed the size and frequency of U.S. retaliatory strikes steadily rose in response to these new threats. In December, higher command authority urged field commanders to be more aggressive and flexible interpreting existing restrictions. Soon after the General John Lavelle, the Seventh Air Force commander, began to adopt a “more vigorous protective reaction posture.”10 The first three months of 1972 saw more than 90 protective reaction strikes launched, compared to 108 during all of the previous year in what was quickly evolving into a new de facto bombing campaign.11

The opportunity to take advantage of looser rules of engagement to launch, what were in effect, preemptive strikes into North Vietnam came at a critical moment for the United States. With the Paris talks going nowhere, it appeared that Hanoi was increasingly willing to let the momentum of the U.S. troop withdrawal and American anti-war sentiment box Nixon into a corner. And despite the bellicose rhetoric coming out of Washington, there was no turning back on Vietnamization and stricter U.S. congressional oversight of the war in the aftermath of the secret bombing of Cambodia and the 1970 incursions gave Nixon little military leverage. This left him with few options other than the escalation of protective reaction strikes. Moreover, this use of air power had several advantages. First, it allowed Nixon and Kissinger to forcefully remind Hanoi that the war was far from over in the hope of reinvigorating the peace talks. Second, it had the military benefit of disrupting North Vietnamese offensive preparations, while also signaling ever more fierce retaliation should the North escalate its activities. Finally, it permitted the administration to tacitly circumvent congressional opposition to any expansion of American military action north of the DMZ. All this was important as it seemed merely a matter of time before Hanoi was likely to take advantage of the declining American military presence to test the mettle of Saigon’s forces.

For the senior North Vietnamese leadership, 1972 was indeed shaping up well, a year that they believed would see the realization of their longstanding dream of freeing the Vietnamese people from foreign rule and influence once and for all. Since the death of Ho Chi Minh in September 1969, power within North Vietnam had become concentrated in the hands of Secretary General Le Duan, Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, and General Vo Nguyen Giap, all of whom were ardent nationalists united in their commitment to defeating the United States. They were, however, also pragmatists. The defeat of the Americans could come either on the battlefield or at the negotiating table. Thus, for the past several years they pursued their own version of a fight and talk strategy that sought political concessions from the Americans in Pairs, while also preparing to militarily defeat the United States and its Saigon ally on the battlefield.

Now it seemed that the stars were beginning to align in mid-February 1972 as the Year of the Rat began. With Nixon facing reelection in the face of an unpopular war, North Vietnamese leaders reasoned that his hands would be increasingly tied by domestic political considerations. Likewise, the White House’s public commitment to de-escalating the war through troop withdrawals and the small size of the remaining U.S. forces in Vietnam would likely limit Washington’s ability to respond militarily. And even if the Americans resorted to bombing of the North again as they had threatened, the North Vietnamese had weathered the storm before during Operation Rolling Thunder and could do it again. Besides the Soviets and Chinese were likely to denounce any renewed bombing campaign and put diplomatic pressure on the Americans to stop it.

The powerful Secretary General of the Vietnamese Communist party, Le Duan, gambled on achieving a military victory by launching the Easter Offensive on March 30, 1972 rather than pursue a negotiated settlement to the war with the Americans.

Militarily things were looking up for Hanoi too. Its forces and logistics network in Cambodia had been reconstituted since the 1970 U.S.-South Vietnamese incursions and were ready along with their Viet Cong allies to go over to the offensive. American air interdiction efforts over southern Laos and the North Vietnamese panhandle, as well as Operation Lam Son 719, had caused some disruptions, but not enough to prevent Hanoi from being able to amass large numbers of men and matériel along the South Vietnamese border. In addition, the poor performance of ARVN troops during Lam Son 719 not only boosted the confidence of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) in its ability to go toe to toe with the ARVN and win, but it validated Hanoi’s belief in the failure of Vietnamization.12

Not surprisingly then, in mid-1971 the politburo of the North Vietnamese communist party had determined that “the time has come to bring about a favorable moment” and “intensify our struggle” [through military action to] achieve a decisive victory in the year 1972 and compel the American imperialists to end the war through negotiations on our terms.”13 Accordingly, military planning for a general offensive—along the lines of the 1968 Tet Offensive—to strike a crushing blow against the Saigon government kicked into high gear. After approving the plan, which called for a large-scale conventional assault using tanks and heavy artillery into the northern provinces of South Vietnam combined with diversionary attacks in the far south and central highlands, the politburo was increasingly confident of victory. The objective of the offensive would be to capture and hold the northern provinces of South Vietnam while engaging and destroying large numbers of South Vietnamese troops. This in turn would lead to the complete collapse of Saigon’s military and the implosion of the regime.

Since the end of Rolling Thunder and the bombing halt in November 1968 Hanoi had steadily and systematically rebuilt the North’s transportation, industrial, and military infrastructure. By the early 1970s, Hanoi was working feverishly to improve its logistic capability, strengthen its air defenses, stockpile supplies and equipment, and create new troop staging areas across the southern panhandle. Petroleum pipelines were being built through the Mu Gia Pass on the Laotian border and to just north of the DMZ and construction was also underway to extend the North Vietnamese road network into South Vietnamese territory.14 Work on improving the airfields at Quang Lang, Vinh, and Dong Hoi was in progress too. Thus, Hanoi’s southern panhandle was fast becoming a well-equipped and -defended arsenal, bristling with growing numbers of men and equipment.

This changing situation was not lost on the Americans. With a new sense of urgency Washington ordered a number of large-scale preemptive strikes against this build-up. Operation Prize Bull was launched on September 21, 1971 during which 196 aircraft stuck POL (petroleum, oil and lubricants) storage facilities south of the 19th parallel and destroyed an estimated 470,000 gallons of capacity and starting several huge fires.15 Following several attempts by VPAF MiGs to intercept and shoot down B-52s operating over Laos in October, U.S. Air Force and Navy planes also attacked the airfields at Quang Lang, Vinh, and Dong Hoi in early November. The White House publicly claimed that these were simply retaliatory strikes, but the Pentagon tacitly acknowledged that the bombing was also being done “with an eye toward stopping any major buildup before it develops.”16 Hanoi was being put on notice.

The North Vietnamese politburo seriously underestimated the political will of Washington and capability of American air power to respond forcefully to Hanoi’s aggression in the South. (Photo Naval History and Heritage Command)

As if to remove any sense of pretext as to what was evolving into an American interdiction effort over the North Vietnamese panhandle, Operation Proud Deep Alpha was launched on December 26. The five-day operation—the largest series of airstrikes since the 1968 bombing halt—was designed to destroy MiG fighter aircraft on the ground and render the airfields at Quang Lang and Bai Thuong inoperable, while also targeting fuel and supply depots, SAM sites, and truck parks below the 20th parallel.17 More than 1,000 sorties were flown, but poor weather hampered the effectiveness of the strikes. A number of POL storage facilities were moderately damaged and the runway at Quang Lang was heavily cratered. At least 45 SA-2 surface-to-air missiles were fired at the attackers and three struck home, resulting in the loss of an Air Force F-4D Phantom, a Navy F-4B Phantom, and a Navy A-6A Intruder.18

Since the end of Operation Rolling Thunder in November 1968, U.S. air operations over North Vietnam became limited to reconnaissance collection missions with accompanying fighter escorts. Moreover, under highly restrictive rules of engagement American aircraft undertaking these missions were only permitted to defensively respond to “hostile actions” directed against them. They were strictly prohibited from initiating any offensive actions. By late 1971, however, American aircraft overflying North Vietnam and those conducting air operations in neighboring Laos found themselves under increasing threat as Hanoi built up its air defenses in the southern panhandle of North Vietnam. In the final three weeks of December alone ten aircraft and 13 crewmen were lost over southern Laos. Reconnaissance flights over the North also found themselves facing a growing threat south of the 19th parallel from newly established surface-to-air missiles sites, a rising number of anti-aircraft guns, and increasingly aggressive MiG fighters.

To counter this threat and send a message to Hanoi, the Joint Chiefs urged Air Force and Navy field commanders to be more aggressive and flexible in interpreting the existing rules of engagement. Authorization was also given in December 1971 to increase the number of fighter escorts on reconnaissance missions from two to eight or even 16 if need be “to insure adequate damage” to enemy defenses when fired upon. General John Lavelle, commander of the Seventh Air Force since August, saw this as endorsement of higher command authority to escalate protective reaction strikes over the southern panhandle of North Vietnam. Thus, not only were the offending air defense sites to be attacked, but associated airfields, radars, SA-2 missile transports, fuel supplies, and ammo dumps became fair game. According to General Lavelle, “We went in after these targets, the ones that would hurt the enemy’s defensive system, so that we could operate.” These “ad hoc” reactive airstrikes were in addition to a growing number of planned larger scale protective reaction strikes, like December’s Proud Deep Alpha operation, in what was quickly becoming a new air campaign over North Vietnam’s southern panhandle by 1972.

Back channel reports of Lavelle’s “unauthorized bombing” of the North came to light in early March 1972 and resulted in a congressional inquiry. A subsequent investigation by the Air Force Inspector General determined that Lavelle had conducted 28 unauthorized missions, consisting of 147 sorties, as well as finding out that that the Seventh Air Force had deliberately falsified reports to hide the activity. Air Force Chief of Staff General John Ryan immediately recalled Lavelle in April, telling him of his plans to relieve him of command. This effectively ended Lavelle’s career and he chose to retire at the rank of major general. Lavelle was replaced by General John Vogt as the Seventh Air Force commander on April 10.

Lavelle consistently defend his actions, telling congressional leaders that he believed he was acting on orders from higher command and that the charges were “a catastrophic blemish” on his military record “for conscientiously doing the job I was expected to do.” Nonetheless, General Ryan and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Admiral Thomas Moorer, testified that they were unaware of any falsified reports and that Lavelle was not encouraged—officially or unofficially—to stretch the rules of engagement. The White House also publicly said his actions were not authorized and “it was proper for him to be relieved and retired.” In 2007, however, the discovery of White House recordings from the Nixon archives showed that President Nixon had indeed authorized the bombing and that Nixon and Henry Kissinger struggled with the decision to make the White House’s involvement public. “I don’t want him [Lavelle] to be made a goat, god damn it. Frankly, Henry, I don’t feel right [about this] and “I don’t want to hurt an innocent man,” said Nixon in a June 1972 recording. The potential political blowback, however, apparently proved too much for Nixon and Kissinger. Both remained silent. Thus, it turns out that Lavelle was right all along: he had been made a public scapegoat for a policy that was militarily sound, but politically insupportable.

Sources: J. Morrocco, Rain of Fire, pp. 104-105; Washington Post, August 5, 2010.

Likewise, two days of intense airstrikes in mid-February 1972 were launched to silence North Vietnamese long-range artillery just north of the DMZ that had begun shelling ARVN outposts to the south. In addition to attacking the artillery positions, logistics complexes and newly discovered SAM sites were also targeted. MACV claimed the attacks were successful in damaging or destroying seven 130-mm artillery pieces.19 At least 81 SA-2 missiles were fired at the American attackers and two found their mark: an Air Force F-4D Phantom and an F-105G Wild Weasel (a specialized air defense suppression aircraft) were downed by the missiles and a third Air Force F-4D was lost to ground fire.20 Despite the increasingly aggressive nature of American airstrikes and Washington’s stern warning to Hanoi not to take advantage of the drawdown in U.S. forces, the North’s preparations for the 1972 offensive continued unabated. The North Vietnamese were not about to be deterred; the die was clearly cast.

Despite ongoing U.S. and South Vietnamese interdiction efforts against the Ho Chi Minh Trail, Hanoi was able to amass several hundred thousand men and stockpile large amounts of supplies and military equipment along the borders of South Vietnam by early 1972.

The South Vietnamese incursion into southern Laos during Operation Lam Son 719 in early 1971 proved not only unsuccessful in significantly disrupting and destroying the enemy’s logistics infrastructure and supplies, but demonstrated a weakness in Saigon’s forces that Hanoi sought to exploit in the coming year.

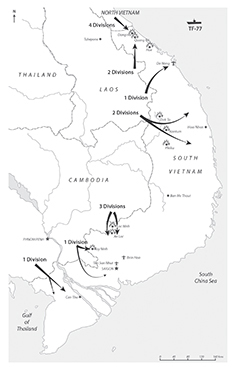

In the early morning hours of March 30, 1972 the still of the jungle was broken with the sound of tanks, heavy artillery, anti-aircraft guns, and some 40,000 NVA soldiers surging across the DMZ and eastern Laos into the northern South Vietnam. The invasion was on. In less than a week other North Vietnamese and Viet Cong units were crossing the border from the Parrot’s Beak area of Cambodia to threaten strategic provinces north of Saigon. By mid-April government forces in the central highlands also found themselves under attack from NVA troops pouring across the Laotian border. In due course as many as 200,000 men along with T-54 main battle tanks, 130-mm towed artillery, ZSU-57 self-propelled anti-aircraft guns, and hundreds of trucks and armored personnel carriers were engaged across three battlefronts.21 It was becoming increasingly apparent that Hanoi was intent on unleashing the largest and most sustained assault on U.S. and South Vietnamese forces in four years. It was surely a bold gamble by Hanoi, but the reward—if successful—was well worth the risk of ending the war in a single stroke.

Although not unexpected by any means, the sheer magnitude and breath of the “1972 Spring-Summer Offensive” (as the North Vietnamese called it) caught Saigon and Washington off guard, as did the willingness of NVA commanders to commit massed armored-infantry columns with supporting artillery and mobile air defense units to the fight. Under the weight of this conventional onslaught, many South Vietnamese units began to buckle and flee. Within a week ARVN bases south of the DMZ were completely overrun and a disorganized retreat toward the provincial capital of Quang Tri was underway. Heavy cloud cover and confusion on the ground prevented any effective U.S. or South Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF) response, but the timely arrival of South Vietnamese Marines and other ARVN reinforcements allowed resistance to stiffen just north of Quang Tri.

Easter Offensive, 1972.

In the far south the town of Loc Ninh across the Cambodian border quickly fell on April 7 with the loss of more than two-thirds of its garrison. Soon the vitally important town of An Loc astride the main highway to Saigon was fighting for its life too. By April 12 the city was completely cut off and under heavy NVA mortar and artillery fire. The third prong of Hanoi’s offensive saw dozens of government outposts and fire support bases in the central highlands overrun and by April 24 its forces were advancing on Kontum and Pleiku. By the end of the month Kontum was nearly surrounded and it was on the verge of falling.22

It was air power, however, that saved the day. Bad weather and poor visibility, lack of communications and coordination with ground forces severely hampered air operations in the early days of the offensive. Thus, NVA commanders took full advantage of the situation to press home their assaults and even brazenly took to open highways, driving fleeing ARVN soldiers and frightened civilians ahead of them. But as the weather improved and battle lines stabilized, American and South Vietnamese aircraft took to the skies to rain down torrents of bombs and hails of gunfire on the attacking columns. B-52 sorties rose dramatically from 700 in March to 1,600 in April to a peak of 2,000 in May.23 Soon every available American plane and crew in Southeast Asia would be scrambled to stem the tide.

As the fighting at An Loc grew increasingly desperate, U.S. Air Force and Navy F-4s, along with VNAF A-1 Skyraiders and A-37 Dragonfly attack jets, relentlessly pounded attacking NVA infantry formations with napalm and 500-pound bombs. U.S. Army helicopter gunships also joined in by blasting enemy T-54 tanks with anti-tank rockets and waves of B-52 bombers out of Guam unloaded their massive payloads against enemy buildups on the outskirts of the city. Badly shattered, the remaining communist forces settled into a siege of the city by the end of the month.24

In the far north of the country, tactical airstrikes, artillery barrages, naval gunfire, and B-52 Arc Light strikes stiffened the resistance outside Quang Tri and slowed the enemy advance by inflicting heavy casualties.25 Dozens of T-54 and PT-76 tanks were smoldering wrecks. Row after row of bomb craters littered the landscape approaching the city and hundreds of NVA soldiers lay dead on the battlefield. While overwhelming firepower bought time for the defenders, four weeks of fighting had taken its toll. The 3rd ARVN Division was completely mauled and ceased to exist. Abandoned artillery and other cast-off military equipment marked the line of retreat southward from the DMZ and even elite South Vietnamese Ranger and Marine units had their ranks decimated. There was very little left and on May 1 all resistance at Quang Tri collapsed. The ensuing retreat quickly became a rout in the chaos that followed. Intermingled fleeing troops and civilians were forced to run a gauntlet of enemy artillery and gun fire as they raced southward down coast Highway 1 to the promised safety of the old imperial capital of Hue. Only the bravery and determination of an ad hoc force of South Vietnamese Marines, Rangers, and tanks fighting a rearguard action staved off complete disaster.26 On May 3 the last remnants crossed the Thac Ma River. Quang Tri Province was now completely in the hands of the North Vietnamese.

A North Vietnamese heavy artillery battery unleashing a deadly barrage against South Vietnamese positions south of the DMZ as the Easter Offensive kicks off.

In the space of a few weeks some 200,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops poured across the South Vietnamese border on three fronts, pushing the defenders to the brink of disaster. 31

Things weren’t much better in the central highlands either as the North Vietnamese closed in on Kontum in the early days of May. Meanwhile, other increasingly isolated central highlands outposts were simply abandoned with the defenders leaving artillery, munitions, and mountains of supplies behind. Unfortunately, this forced tactical air-strikes to be diverted to destroy the equipment and supplies before they fell into enemy hands. Once again it was air power that came to the rescue of the beleaguered forces with VNAF and U.S. aircraft, including AC-130E Spectre gunships with their 40-mm and 20-mm mini-guns, blasting massing troop formations to break up their assaults. B-52 strikes were also used as close-in support, often dropping their loads within 1,000 meters of friendly troops. All this proved extremely devastating and by one estimate 40 percent of the NVA force attacking Kontum was killed by May 14.27

In addition to flying tactical air support missions, both American and South Vietnamese aircraft played an equally crucial role in the first six weeks of the offensive by resupplying embattled garrisons and rushing reinforcements to the battle. Moreover, the role of cargo transport crews in braving intense small-arms and anti-aircraft fire—including the first use of the shoulder-fired SA-7 Strela surface-to-air missiles—proved to be decisive in the defense of both An Loc and Kontum. This was not without cost: three C-130 Hercules transports were lost to ground fire over An Loc during the siege of the city. Often overlooked too was the essential role of Air Force and Army airborne forward air controllers in identifying and marking targets and coordinating airstrikes. These small, low-flying aircraft were highly vulnerable and seven were lost to ground fire or SA-7s by mid-May.28

ARVN troops in Quang Tri Province in the far north of the country were quickly overwhelmed by the North Vietnamese onslaught.

Although months more of hard fighting still lay ahead and the battlefield situation remained precarious, the North Vietnamese offensive clearly had been blunted and with it Hanoi’s best chance of militarily altering the political dynamic in Paris. Thanks to the overwhelming air response, the North had paid dearly in losses of men and equipment and Saigon’s battered and demoralized forces had gained desperately needed breathing space to prepare for the next round. The battle, however, was far from over. Much more still needed to be done. It would come in the form of Operation Linebacker and the air war returning to the skies over North Vietnam with a vengeance. Now it was the Americans’ turn to turn the tables.

An American adviser looks on as South Vietnamese officers attempt to grapple with the unfolding offensive. Unlike the 1968 Tet Offensive no U.S. ground troops would be coming to the rescue.

Between April 18 and May 3, three of the big C-130 transports would be lost to enemy ground fire while resupplying the embattled garrison at An Loc. (Photo National Museum of the U.S. Air Force)