Over the course of the most intense six months of air operations in 1972 against the North—Operations Linebacker I & II—American pilots would fly almost 44,000 combat sorties and drop 175,918 tons of bombs.1 It was, however, those eleven days in late December that would produce the most iconic images of massive B-52 bomber unleashing 15,237 tons of bombs on 34 targets across the North Vietnamese heartland.2 The North responded as best it could with MiG fighters, intensive anti-aircraft barrages, and by launching between 800 and 1,200 SA-2 missiles.3 At day’s end, the 1972 campaign would cost the United States 107 aircraft—including 15 B-52s—and the lives of 93 pilots and crew to hostile fire; the VPAF lost 68 fighter aircraft in return.4

While this would be the final act of America’s eight-year, on-again-off-again air war against North Vietnam, it would set the stage for a debate over the role and effectiveness of the bombing—and particularly of Linebacker II—in ending the war and in the broader historical context of the utility of using air power to advance political objectives.

Certainly the 1972 air campaign inflicted substantial damage to the North Vietnamese economic and military infrastructure and hindered Hanoi’s war-making capability. The ongoing destruction of bridges, rail links, truck repair and storage facilities, and transshipment points diverted extensive manpower and material resources into repairing and maintaining some semblance of the country’s transportation and logistics network. By the late summer the flow of supplies southward had been sharply reduced and it was believed that less than 20 percent of previous supplies were actually reaching frontline North Vietnamese units.5 Industrial production likewise suffered as a result of repeated airstrikes and large quantities of war matériel and supplies went up in smoke under the weight of American bombing. Linebacker II alone was credited with damaging or destroying 1,600 military complexes, 372 rail cars, 25 percent of POL stockpiles, and 80 percent of the North’s electrical power production.6 In addition, the once-vaunted North Vietnamese air defenses were shattered by the end of December; surface-to-air missile inventories had been largely exhausted or destroyed and the once potent MiG fighter threat largely neutralized, leaving the North as exposed and vulnerable as ever.

There can also be little doubt that overwhelming American and South Vietnamese air power was a decisive factor in smashing the North Vietnamese Easter Offensive and eviscerating Hanoi’s attempt to achieve a conclusive military victory over the Saigon government in 1972. Moreover, Hanoi was clearly caught off guard by the American response and Nixon’s willingness to escalate at a time when the United States was militarily disengaging from Southeast Asia. Thus, for the second time in four years Le Duan was forced to adopt a longer-term political strategy to defeat the Thieu government and its American ally.

In contrast, the Nixon White House was forced to rely on its last remaining form of military leverage in Vietnam, air power, to achieve its political objective of a negotiated peace settlement. Starting with Freedom Train and its evolution into Linebacker I, the escalating American bombing campaign against the North was driven by the need to interdict the flow of men and matériel southward. Although past interdiction efforts had come up short, the Americans had little choice; it was either that or face the collapse of the Saigon government. The largely successful effort this time, for it surely stymied Hanoi’s efforts to resupply and reequip its forces in the South, was a result of the enormous amount of American air assets committed, the willingness to mine North Vietnamese ports, and the conventional nature of the North’s military in 1972. Air power proved to be the right tool at the right time.

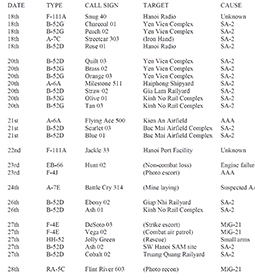

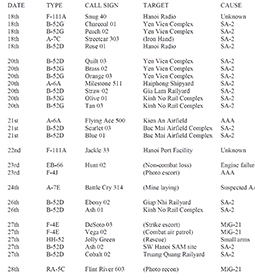

Table: U.S. Aircraft Losses, Linebacker II, December 18-28, 1972

Sources: Project CHECO, “Linebacker Operations, September-December 1972,” Appendix 5, p. 95; C. Hobson, Vietnam Air Losses, pp. 242-246.

Time, however, was working against both the Americans and North Vietnamese and it would ultimately drive Washington and Hanoi toward a compromise. Nixon needed to get out of Vietnam. Despite his recent reelection, Nixon’s room for maneuver was quickly evaporating as congressional pressure was mounting and the final withdrawal of U.S. troops was underway in early 1973. Le Duan needed the Americans out of Vietnam. Given time to rebuild and reequip, the North was confident of victory over the Saigon government once the weight of American support was removed. Likewise, Hanoi was under growing pressure from its key allies, Moscow and Beijing, to reach a peace agreement as Washington’s policy of détente and rapprochement began to bear fruit. All that was now needed was a final catalyst for action.

Linebacker II prove to be that catalyst by serving notice that the Americans were willing to inflict even more military, economic, and psychological pain on the North Vietnamese to achieve a politically acceptable settlement. Since Hanoi was getting most of what it wanted, i.e., troops remaining in the South and control over territory it occupied there, it was not worth the risk of calling Washington’s hand. Importantly too, President Thieu got an unequivocal message of current American military support and assurances of future treaty enforcement should Hanoi violate the ceasefire. This proved to be enough to overcome the last remaining obstacles to peace and within weeks Kissinger and Tho were able to finalize a peace agreement that both sides could claim as a victory.

The use of air power this time made a difference both militarily and politically, largely because of timing and the confluence of events that made the war ripe for a peace settlement at the end of 1972. Conditions that were not in existence a year earlier let alone in 1968 when both sides were seeking to overcome adversity and still held out hope of victory on the battlefield. Neither side got all they wanted, but each got just enough. To their credit Washington and Hanoi realized this time there was a window of opportunity for peace and seized it. This was the final tribute to the warriors of the 1972 air war.