IT WAS PRIOR to the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, and I was sitting down with an athlete for the first time to discuss supplementation.

The athlete began putting supplement containers on the table, one by one. And on it went, to the point that one of the coaches walking past asked if we were playing chess. In the end there were on the table no fewer than 28 different supplements that were part of this athlete’s current regime.

So we started from the beginning: I asked for a rationale as to why he was taking each one. He started off with the ones he considered the most important, and there were some solid responses:

‘Energy on competition day.’

‘To boost my immune system during the winter.’

‘To help improve my strength during training.’

‘As an insurance policy, in case I’m missing anything from my diet.’

But as we went down the list, the answers became more hazy:

‘I’m not sure – I haven’t taken that in a while.’

‘My wife said this is good for me.’

‘An old trainer recommended that for me.’

This meeting went on for a while. And this was before we’d even got into discussing whether the supplements were effective, safe or where they had come from (the sourcing). This last point is extremely important because athletes are governed by WADA (World Anti-Doping Agency) rules, and not only drugs, but also dietary supplements can contain banned substances that can cause an anti-doping rule violation.

With this athlete’s training, everything was meticulously planned and executed, but when it came to supplementation there was no process – everything was just thrown together.

This is an extreme example, and obviously you’re probably not going to be subject to random drug testing any time soon. But there are some parallels here that will apply to you if you’ve ever taken dietary supplements, even if that’s just in the form of something like a vitamin tablet or protein shake, and particularly if you are looking into supplementation more seriously as part of a training plan.

So, just as I did with this athlete, I want you to get your supplement bottles on the table and think about why you’re taking them: all of them.

Write down each supplement you have taken over the last six months, along with the reason why you took it. We will revisit this later on.

One thing I want to make absolutely clear from the start of this chapter: there are very few supplements that actually work.

The world of supplementation can feel a bit like the Wild West at times, awash with confusion and contradictory advice, and it’s little wonder. The supplement industry is expected to be worth around 220 billion dollars by the year 20221 and the multinational companies behind supplements have an arsenal of seduction techniques – traditional channels such as magazine and billboard advertisements, the Instagram influencers subtly beckoning you with their ripped bodies and legion of followers to the product in their hand, even that helpful person at the health-food store or the personal trainer at your gym – to convince you that their supplements could change your life. The influencers can be even closer to home – maybe you have a friend, colleague or partner telling you about the fantastic results the product they’ve been using has yielded.

As many as 93 per cent of elite athletes have used supplementation in recent years,2 and their use among the general public has been on the rise over the last decade too; dietary surveys in the USA, for example, suggest that it’s currently a whopping 50 per cent.3

A common comment I hear is ‘But they’re only supplements – what harm is taking some extra vitamins going to do?’ It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that because something is good for us – or, with something like vitamin C, necessary to us – it’s a case of the more the better. We’ve seen this before with so-called ‘good’ foods – have a dollop of coconut oil here and a handful of nuts there, wash it all down with a kombucha drink in the misguided belief that this will make us more healthy.

With supplementation, just as with any type of food you consume, often the dose makes the poison. Mega-dosing (high doses well above the RDA) is common, as we often fall into the trap of thinking a little bit more will yield even more benefit, forgetting that fact that supplements can have powerful effects, not just positive but negative too.

In fact, it has been shown that large doses of vitamin C (1,000 mg per day and upwards) and vitamin E (235 mg per day and upwards) may negatively impact on how the muscles’ mitochondria – those little power generators in your cells that convert fuel to your body’s preferred energy currency – adapt to endurance training, potentially dampening the effect of your exercise programme and interfering with your Energy Plan.4

And while it’s well known that iron deficiency and anaemia impair athletic performance, so too does too much iron; supplementation when iron levels are already sufficient can cause iron overload, highlighted by blood markers in up to one in six recreational male runners.5 We shouldn’t be using supplements if levels are already sufficient, and the only way to be sure of your levels is with a blood test. So exercise caution.

However, when we’ve been training hard, working hard and trying to fit in a social life around it we can feel like we’re in need of some extra help for another big day tomorrow – so when should you consider supplementation?

Stephen Covey, author of The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, talks about getting what he calls the ‘big rocks’ – the most important priorities – in place first. And we can borrow this approach when we look at supplementation. Instead of immediately turning to a supplement, we should look at our big rocks, those key elements that we have been discussing throughout the Energy Plan, which are:

Next to these, supplements are simply pebbles and sand. Used appropriately, yes, they can play an important (if small) part in your Energy Plan, but it’s the big rocks that will make the more meaningful difference to your results and life, and it’s pointless getting started with supplements without having those in place first. As emphasised throughout this book, the Energy Plan’s approach to nutrition is a food-first one, as this is where we can make the biggest gains.

At the start of this chapter I asked what supplements you’d taken over the last six months and why.

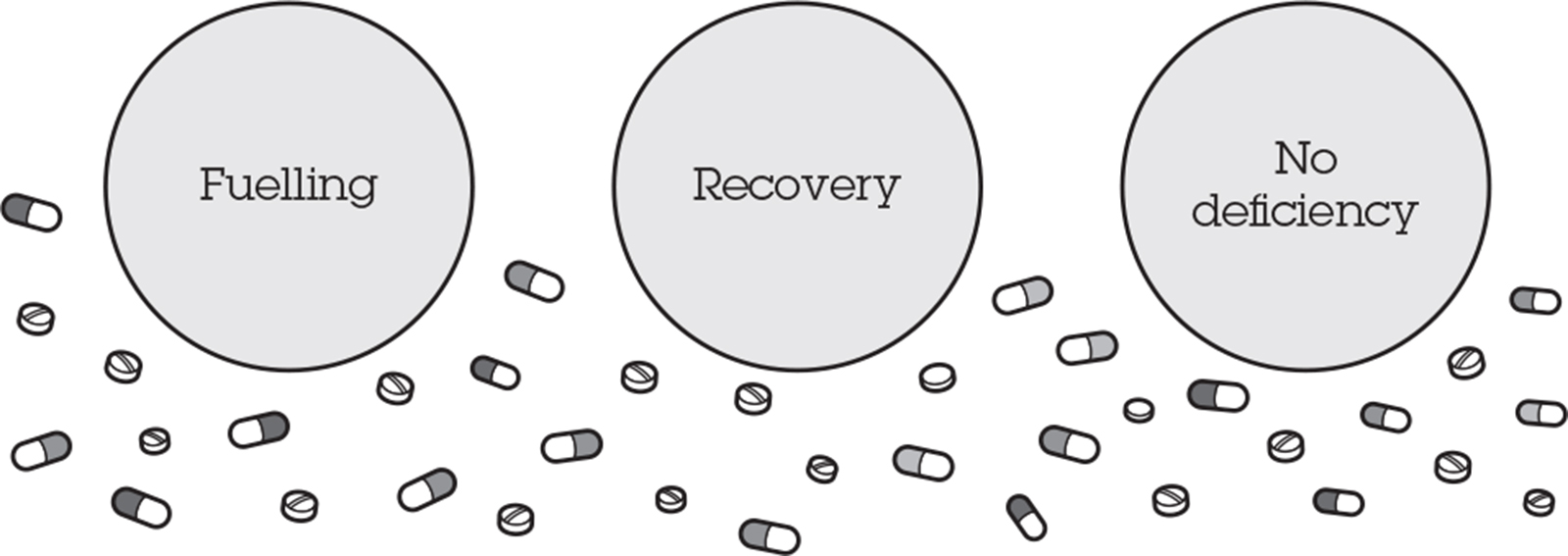

I see so many people whose list of supplements, just like that of the athlete we met earlier in the chapter, has built up year after year to the point that their kitchen cupboards are filled to bursting. And when I ask why they take each individual supplement, or if they know if they even need to, they can’t tell me. Below are some of the most common reasons why people take supplements. Do any of them tally with what you’ve written down?

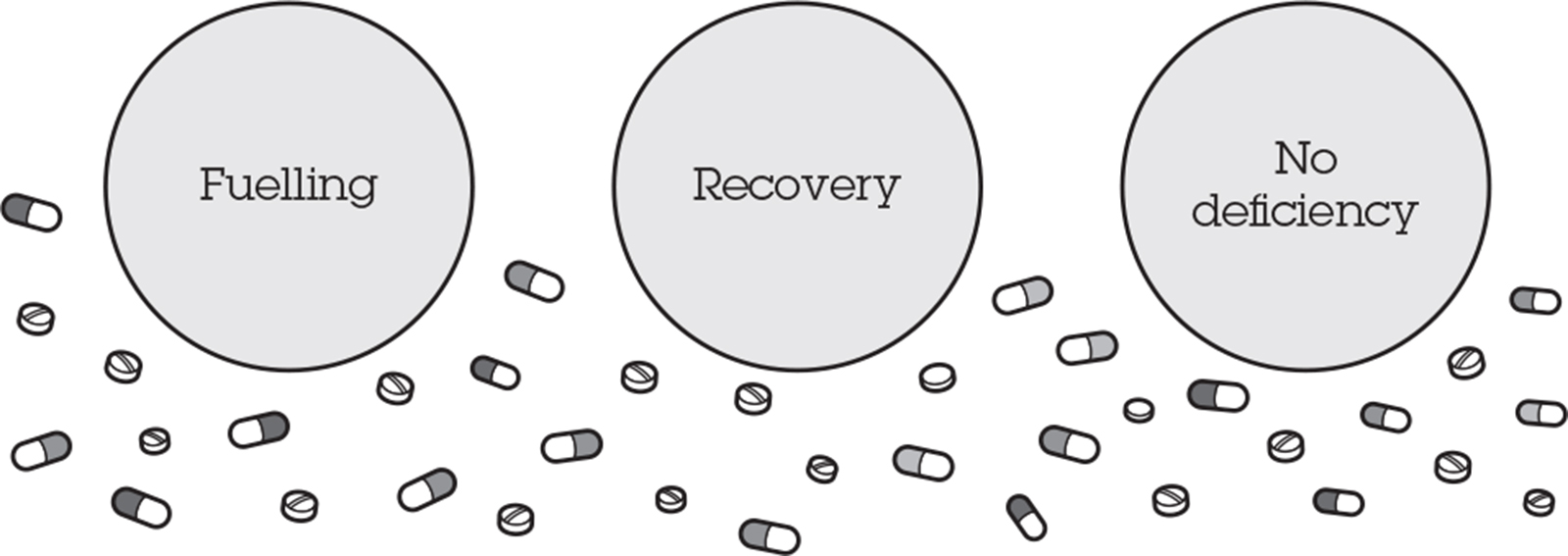

So before we address whether using a supplement is a good idea, it’s important to define the supplements that actually work according to their role – why you would use them. There are three main categories of supplementation that we use in sport:

Sports drinks, probably the most commonly used and recognised sports ‘food’, provide both fluid and carbohydrate during exercise. These typically contain around 6 per cent carbohydrate (so a 500 ml bottle delivers around 30 g carbohydrate, a key amount that we discussed in Chapter 3), and also sodium, which promotes fluid absorption.

Gels typically contain around 25 g carbohydrate for use during exercise, whereas confectionery such as shots or chews deliver around 5 g per piece (35–50 g per packet). These often also contain electrolytes, and sometimes caffeine.

Mainly for use in post-training recovery, potentially in combination with carbohydrate (for refuelling), they are a convenient snack to meet daily protein needs or for use during travel.

Protein supplements may come in powder form, from animal (such as whey or casein) or plant (soy, rice or pea) sources. These typically provide between 20–50 g per serving (see protein recovery, Chapter 3, here).

Protein bars offer a solid alternative to the powder form, and broadly fall into two categories – low- or moderate carbohydrate.

Protein-enhanced foods are a rapidly developing area of this market. This is when protein is added to more usual foods such as yoghurts, ice cream, cereals and cereal bars.

Meal replacement drinks are used to replace meals during busy schedules and to support either high-energy intakes during weight gain, high training volumes or to replace meals as part of a diet for weight loss. These are typically either high-calorie or low-calorie (depending on their function) and provide a complete range of macro and micronutrients.

High-electrolyte products are for use in replacing large fluid and electrolyte losses from making weight, endurance events or during sickness. They typically contain added sodium and potassium to treat dehydration.

Sports foods are an extremely varied category and the composition of each of these products will vary dramatically depending on the brand, so it’s important to check the label (alongside the source, as we will come on to) to ensure you have the right product.

The two main reasons for taking micronutrients in supplement form are to correct a deficiency in a particular nutrient, and to support immunity (see the immunity chapter for more information).

Micronutrients of which people are most commonly at risk of deficiency include vitamin D, iron and calcium (see Part I, here). Micronutrients such as vitamin C, zinc and probiotics can help to support different elements of immune function.

This is the final category to consider for your Energy Plan, but are only to be considered or used when the ‘big rocks’ are already in place. We’ve already discussed caffeine (see here); these supplements are similar in that they have a direct effect upon performance. They should be considered individually (see overleaf). You should consult a registered sports and exercise nutritionist if you’re considering using any of these alongside your training programme.

Creatine, made from three different amino acids, has been shown to improve performance in repeated bouts of high-intensity work (such as resistance training or sprinting) enhancing training capacity and adaptations (such as muscle strength and power).6 It increases muscle phosphocreatine stores, which recycle ATP, the body’s energy currency, for explosive movements – a far quicker process than that involving carbohydrate.

You could consider using creatine monohydrate (the most effective type) for a period of training in which you are aiming to increase strength and muscle mass, or to enhance training capacity during intermittent training or resistance training programmes.

There is potential for a 1–2 kg increase in body mass if using creatine, through water retention in the muscles, and with appropriate use it has no negative long-term effects. Creatine is found within red meat, poultry and fish, and levels are typically lower in both vegans and vegetarians,7 which means that creatine supplementation maybe an important consideration to support training goals if you follow these diets.

Beta-alanine8 is a newer player on the scene. A non-essential amino acid, it potentially improves high-intensity exercise performance (30 seconds–10 minutes in duration)9 and reduces the acidity in the muscle (the burning feeling), causing fatigue.

It can support exercise capacity during high-intensity training, so may be used for increases in strength and muscle mass, team sports performance or even high-intensity-based training programmes. Sometimes this is chosen instead of (or even used with) creatine, due to creatine’s potential to cause fluid retention.

Dietary nitrate has received a lot of press in recent years in the form of beetroot juice thanks to its capacity to affect many physiological aspects of exercise performance. It can improve endurance performance by reducing the oxygen cost of submaximal exercise, essentially making the muscles more efficient, and may also improve muscle power and sprint exercise performance.10

You could consider using it for endurance-based training, although there is a sound rationale for anyone undertaking hard intermittent training programmes to include more nitrate-rich vegetables as part of their daily protection foods.

A ‘dose’ of nitrate (5 mmol) can be provided by half a litre of concentrated beetroot juice. It’s also found in green leafy vegetables such as lettuce, spinach, rocket, celery, cress and beetroot in its whole form, all of which typically contain over 4 mmol per 100 g fresh weight.11 So that means, for one dose, eating more than 100 g of nitrate-rich vegetables. If taken 2–3 hours before training or competition, concentrated juice or shots are the most efficient, but these need to be trialled as they can cause GI upset.

May also improve high-intensity exercise performance by reducing the acidity within the muscle, prolonging the time to fatigue. A supplement well known to many middle-distance athletes, it has potentially explosive effects if not well managed (it commonly causes gastrointestinal discomfort and diarrhoea). It’s used in very specific training scenarios. So like all supplements, if you’re going to use it, try it in training to see how you react to it.

So, having looked at the supplements that work and which we use in sport, you might be thinking, OK, what others are there? After all, our athlete at the beginning of the chapter had 28 on the table. While we can’t look in detail at every single supplement available, here are some guiding principles on the rest:

Other than increased protein intake, there isn’t anything on the market with strong evidence in this area. These products are some of the most likely to be deliberately adulterated, and if your goal is to reduce body fat, it’s better to use training and food-based nutrition to achieve this.

An essential fatty acid. There’s growing evidence of its benefits in multiple areas such as cognitive function and muscle growth and repair. Increasing intakes in the diet should be the first consideration before you turn to supplements; we looked at this in Part I.

The interest in anti-inflammatory nutrition is on the increase. In this area, tart cherry juice and curcumin may be beneficial in certain situations for muscle damage and inflammation – although due to their potential to dampen muscle response (adaptation), more research is required before these can be recommended.

GELATIN, VITAMIN C AND COLLAGEN

Over fifty per cent of injuries involve musculoskeletal tissues (muscles, tendons, ligaments etc), which are rich in collagen, a crucial substance for making these tissues stronger so that they can better withstand the forces from training.

Professor Keith Baar and his team at the University of California have produced research showing that 5–15 g gelatin enriched with vitamin C, taken an hour before training, enhanced collagen synthesis.12 (Collagen hydrolysate can be an alternative source, for those not able to use gelatin.) Gelatin is a flavourless protein made from the connective tissues of animals, commonly used in jelly, desserts, confectionery and bone broth. This exciting new area of research has seen many professional teams start to make jelly shots for their teams to take an hour before training as an injury prevention strategy.

You can replicate this as part of your own injury prevention strategy, making a jelly shot in the same way as you would make ordinary jelly using gelatin, fruit juice (a flavour of your choice) and water, and ensuring each shot contains a 50 mg hit of vitamin C.

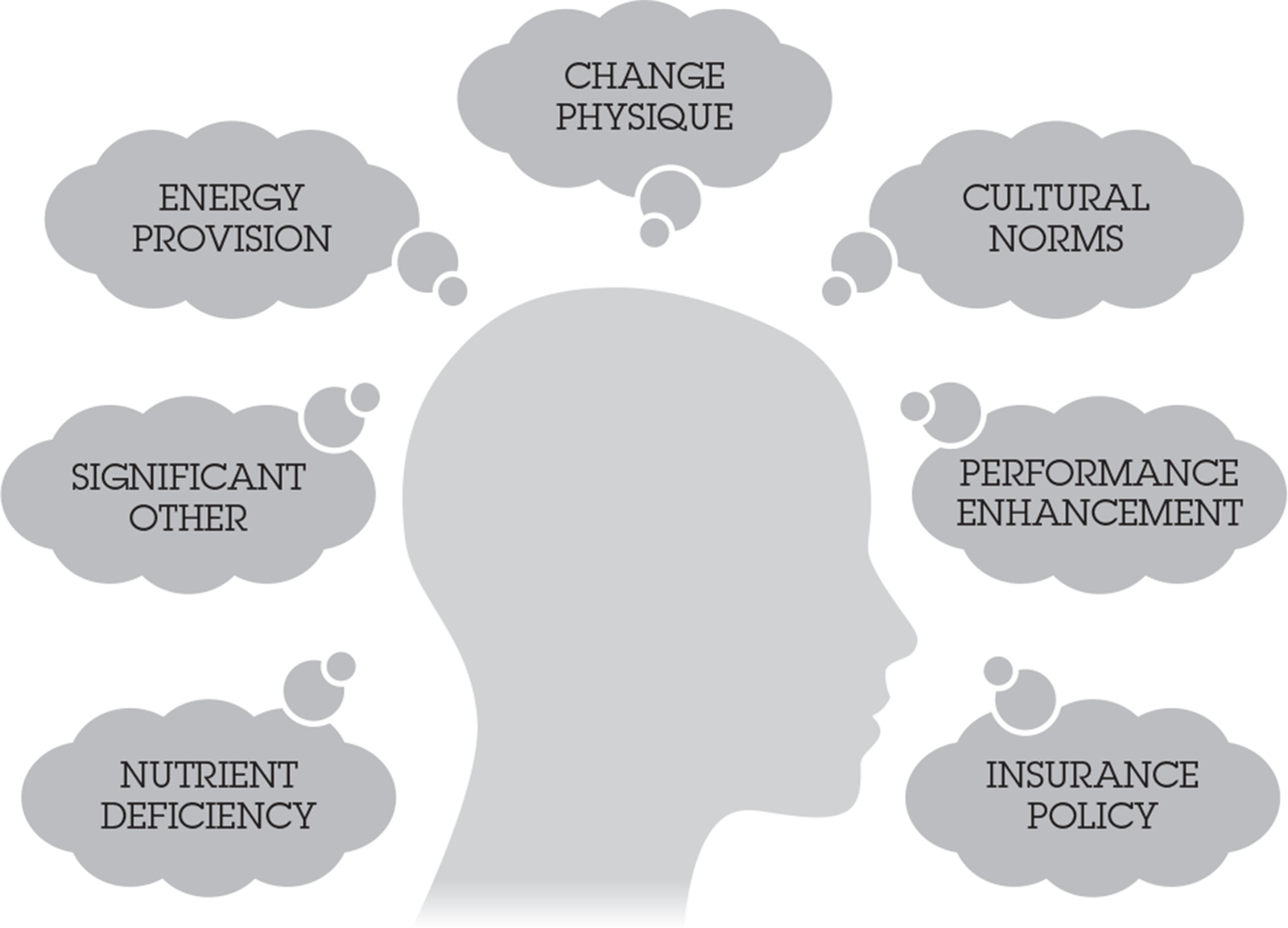

The claims made by supplement brands and ‘health gurus’ are certainly dazzling and authoritative-sounding. Expressions like ‘science-backed’ and ‘evidence-backed’ are common; on the surface this may sound reassuring, but the truth is that supporting evidence can be found for almost anything.

It’s useful to think of the hierarchy of scientific evidence as being a pyramid structure, as in the diagram above. At the bottom of the pyramid is the lowest level of rigour – anecdotal evidence, the thoughts that appear in some online articles and ideas that this might work. At the pyramid’s peak are meta-analysis and systematic reviews, which review all of the available studies that meet the strict inclusion criteria, systematically analysing whether a supplement works and the circumstances in which it is best applied. This is the gold standard in which the available evidence from studies that meet the right criteria are used.

Unfortunately, many ‘science- and evidence-backed’ claims on products come from the bottom rung of the pyramid, which is the kind of unregulated advice widely available in any blog or magazine and is no guarantee that the supplement is effective. So next time you read or hear something in the media about supplements and ‘evidence’, it’s important that you assess whether that evidence is from a credible source.

Most people will read about studies in secondary sources like newspapers or online news outlets. You can easily find out whether a study was a systematic review or something further down the pyramid: often in online articles there is a link you can click to take you to the source; or search for it online by putting in a few key words and names from the story you’re reading.

Supplement manufacturing isn’t as tightly regulated as the pharmaceutical industry. In fact, in most countries supplements are regulated in the same way as food ingredients: there are no requirements to prove their claimed benefits, or show safety with short or long term use or any quality assurance of content.14

While for many people and products the worst might be that the supplement simply does nothing, there are some very real health risks. In the US an estimated 23,000 A&E visits each year are associated with dietary supplements,15 and there have been numerous reported cases of liver toxicity, cardiovascular problems, seizure and even death connected to weight-loss supplements.16 And it’s an international issue. In a number of cases, the problem has been caused by an ingredient in a product not declared on the ingredients list.

There is currently a real disconnect between this area and that of awareness of the food we consume. We live in an age of lively engagement with food provenance and quality: we want to know where our food is grown or reared and the method of its production. We want to know about its journey from its origin to our plate. In restaurants we want to know who the chef is, that the ingredients are seasonal and sustainably sourced. But I’m often amazed at how invested in understanding the journey of their food someone can be, when in the next sentence they say they buy a supplement from the internet or any old brand from a local health-food store.

I want everyone I work with to understand the role of everything that goes into their body – not just food, but supplements too.

This can and does occur in two main ways: through poor quality assurance during production and through deliberate adulteration of otherwise ineffective products.

A landmark study by the International Olympic Committee (IOC)17 found a high prevalence of contamination in commercially purchased supplements (14.8 per cent).

For professional athletes, contamination means they run the very real risk of inadvertently violating anti-doping rules. An average athlete’s career is short; at the very least there could be catastrophic loss of earnings and of course the life-long damage to professional reputation.

OK, you might be thinking, but how does this apply to me?

Well, for starters I’m sure you don’t want to consume things that aren’t on your supplement’s label, any more than you would want ingredients in your food that weren’t on the label. And, as well as substances banned for professional athletes, supplements have been found to contain impurities such as lead, broken glass and metal fragments, as well as substances that could potentially cause harm to health, highlighted by the hospital cases above.18

Within professional sport there are policies on engagement with supplements, education for the individual athletes and even clauses about supplement use in their contracts. When working with professional teams and athletes we used to send supplements to labs to do independent batch-testing for contaminants. This obviously isn’t an option for everybody, but thankfully there are now quality-assurance schemes, such as Informed-Sport.19 This is an independent organisation that batch-tests products and assesses companies’ manufacturing processes, and they make lists of their tested products and brands available to all on their website. Products they have tested and approved carry the Informed-Sport logo. There are still no guarantees, of course, but as part of a risk-management strategy this should be your first port of call.

Some supplements are more high-risk than others. Those purporting to offer anabolic (muscle-building) results are typically at higher risk of contamination, as are weight-loss supplements and herbal supplements, which lack information about the active ingredients or their purity.20

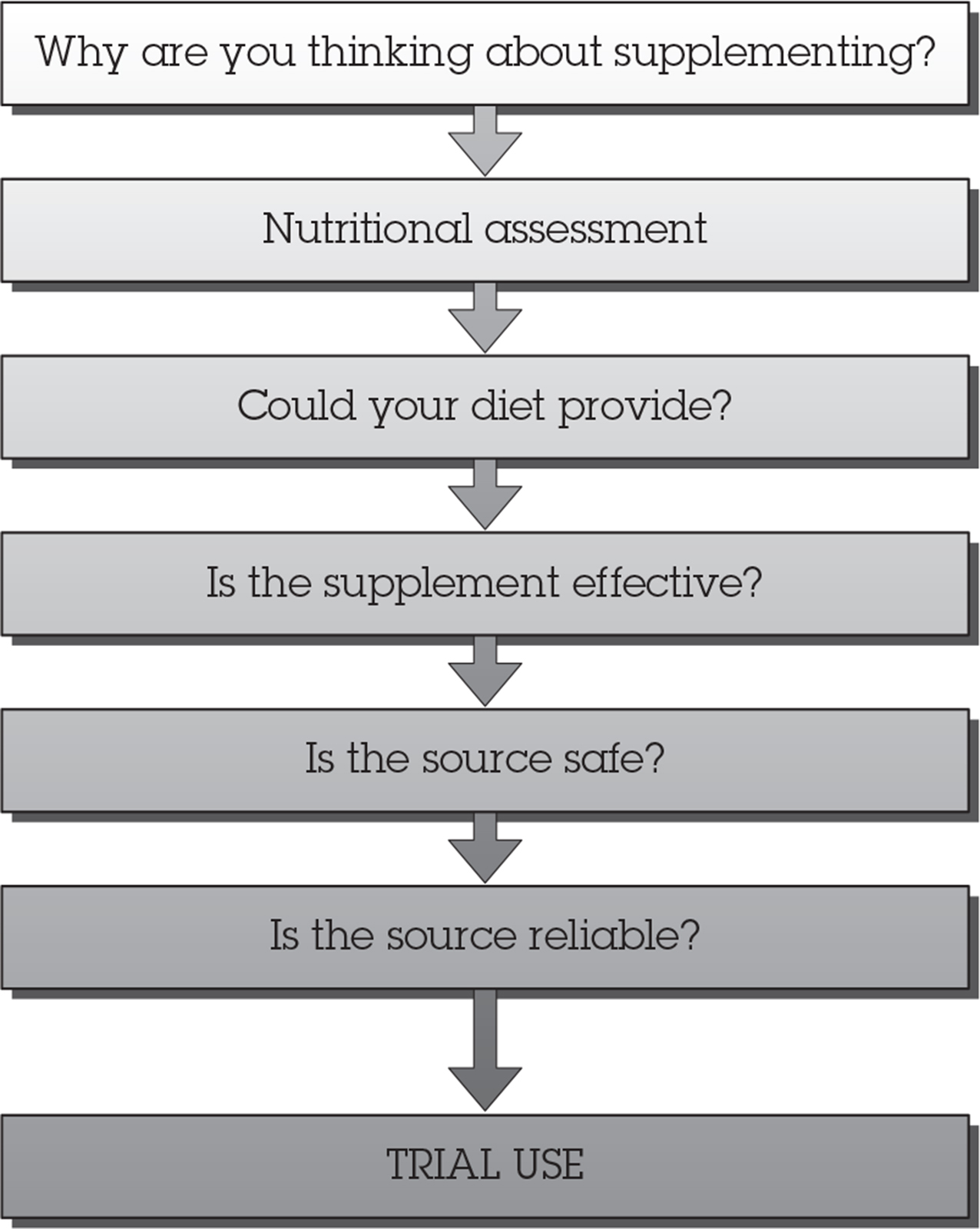

Any decision around supplementation should weigh up the potential costs (financial, side effects) and benefits (training performance, immunity). Use this process to decide whether supplementation should form part of your Energy Plan.

Here is a case study to help:

Jonathan is four months into his Energy Plan. His initial goal was to improve his squash game by making himself faster and more mobile around the court. He has organised his performance plates and snacks within his daily and weekly planners and his monitoring indicates that he’s reduced his body fat and now consistently has more energy during both training and the working day. For the next goal in his Energy Plan he thinks it might be time to turn to supplementation.

1. THE QUESTION

Jonathan is now looking to increase his strength and muscle mass, and he thinks creatine may be the answer.

2. NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT

His dietary analysis highlights that he has the key principles in place from following his Energy Plan.

3. COULD THE DIET PROVIDE?

No. Although he is a meat eater, he can’t gain sufficient amounts from his daily intake.

4. IS THE SUPPLEMENT EFFECTIVE?

Yes. Creatine has strong supporting evidence.

5. IS THE SUPPLEMENT SAFE?

Yes. The long-term studies around creatine highlight that it is safe when taken following the acceptable protocols.

6. IS THE SOURCE RELIABLE?

Jonathan went on the Informed–Sport website and sourced a registered product.

Jonathan made his way through the process and decided to start using the supplement in training.

But what now? When trialling the use of any supplement it’s important to monitor its effectiveness. In Jonathan’s case, it will be important for him to track his weights in the gym, alongside his RPE and body composition. (See the monitoring chapter, here, for more information on this.)

And when priorities change, stop taking the supplement. If strength gains are no longer a focus for you, then this decision-making process will point you away from using it. If you aren’t run down, there is no need to supplement your vitamin C and zinc all year round. Don’t be like the athlete at the start of this chapter, who kept adding unthinkingly to an ever-growing arsenal of supplements. The likelihood is it won’t be helping (and may even be hindering). Instead, when your priorities change, go through the process again to reassess your needs.

Now I’d like you to look at your list of any supplements you are currently taking and go through this decision-making process with each one of them. And remember, as with everything to do with your nutrition, if it’s not helping your work towards the goals of your Energy Plan – what’s it doing there?