HAVING INVESTED TIME and effort in tailoring your eating and training around meeting your goals, you’ll soon want to know that you’re moving the dial in the right direction with your Energy Plan.

Within elite sport we have the ability to measure all sorts of variables to see how athletes are coping with training and optimising performance, from GPS units to measure footballers’ sprints, accelerations and decelerations during training to biomechanics experts looking at long- and triple-jumpers’ technique and trajectory. We can measure a host of blood markers such as hormones, immunity and inflammation, and carry out many other physiological tests. But should we be doing all this?

Such is the pressure in professional sport to deliver winning performances that we’re always looking for the next big thing to help give a competitive edge. This thirst for data and technology is replicated in the public domain; it is estimated that by 2020, there will be 500 million wearable fitness devices being worn.1

But how much information do we really need? In professional sport, we’ve learned that measuring too many things can muddy the water around how the athlete is coping with training. It’s too much information. Just because you can measure everything doesn’t mean that you should. It comes back to the idea discussed at the beginning of Part II: Why the Energy Plan?

Why are you measuring it? Is it essential? What question are you trying to answer?

Let’s return to our boxer at the start of Chapter 4. He needed to reduce body fat in the weeks leading into a fight to make his weight category, a process common in combat sports such as mixed martial arts (MMA) and judo, as well as horse racing. In combat sports a competitive advantage can be gained from training at a heavier weight and then reducing it as the fight approaches.

In the boxer’s case, what he needs to measure is simple, right? – it’s his weight. Well, it’s actually not quite as simple as that. Although the focus is on weight, his body composition will be regularly monitored to ensure he is losing the right type of weight – reducing his body fat while retaining muscle mass. This is before there is even any conversation around dehydrating (a tactic commonly used to ‘make weight’).

This leads us on to the big issue. Overweight, underweight, I need to lose some weight, why does my weight keep fluctuating…? Weight is a heavy word, from which there is no escape in the world of nutrition. But is weight really a good measure of progress when you’re trying to adopt the Energy Plan?

The first place to start is with the age-old rhetoric that ‘muscle weighs more than fat’. In fact, a kilo of muscle weighs just the same as a kilo of fat – and, for that matter, as a kilo of potatoes. What is true, however, is that muscle is more dense than fat, as it contains fibres that contract to allow us to move. So in effect, this means that the equivalent weight of muscle will take up less space than fat: it weighs more in relation to volume.

So if you’re starting a programme of increased resistance exercise and improved nutrition as part of your Energy Plan and you’re using weight as your measure, you might find yourself disappointed by the results. You might find that your weight hasn’t changed much at all, but what might be happening is that your muscle mass is increasing and your body fat reducing. This would happen without there being much change in your weight.

Increasing your muscle mass should, eventually, help get you closer to a more athletic, toned physique. And increasing muscle mass has the double benefit of increasing your capacity to burn more fat, as muscle tissue is more metabolically active than fat, with containing those power generators we introduced in Chapter 1, mitochondria. So the sooner you start incorporating some resistance training to increase your muscle mass, the better you will look and feel, and the better your body will be able to burn fat. It’s a snowball effect – and if you’re simply going by your weight, particularly at the beginning, you might find yourself getting discouraged before you’ve even started in earnest.

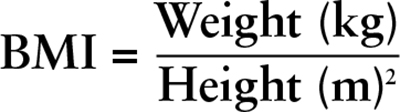

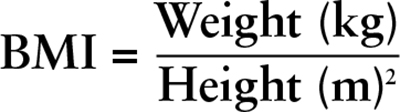

So if weight’s coming up a bit light in its effectiveness, what about that more scientific-sounding stalwart the Body Mass Index (BMI)? The groundwork on BMI was developed in the 1830s by Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian statistician and sociologist, although the term wasn’t coined until the 1970s. BMI is used to determine the body fat content in an individual – or broader populations – by the following calculation:

An individual can then be categorised as being under-, normal, overweight or obese. A BMI of 25 or more is overweight, while the healthy range is 18.5 to 24.9. So, a man who is 1.83 metres tall (six foot) and weighs 86 kilograms (around 13 and a half stone) would have a BMI of 25.7, which is classified as ‘overweight’.

All of which might sound fine until you realise that the BMI isn’t really assessing the body’s fat content at all, and is simply falling into the same trap as those of us gauging progress solely on weight, albeit in this case in proportion to height. A six-foot-tall professional athlete weighing 86 kg would have exactly the same BMI as his couch-potato counterpart. Does that mean the athlete is overweight? BMI is effective enough as a blunt instrument to help health professionals make an initial assessment and for measuring general populations, but for the individual person wanting to assess their body and its changes, it falls a long way short. Our lifestyles have changed a lot since the 1970s, thanks to the prevalence of gyms and our approach to exercise and nutrition, and the BMI feels now like an old-fashioned tool for our needs.

So let’s look at the methods that are more useful to monitor our progress. With each method I have provided both a basic and an advanced option for you to concentrate on depending on your means and how far you want to push things. Anything that involves greater resources, such as a private clinic or a greater investment in your time, will be an advanced option, and there is a suitably budgeted basic option too, which can be just as effective if used correctly. This is about keeping the burden as low as possible – because we all have busy lives – while also ensuring that the results are both valid and reliable. I want you to be able to incorporate this monitoring into your routine without it becoming a pain.

The most effective way to measure how our body is changing in response to training or nutrition is through measuring our body composition, which refers to the key tissues of the body, including body fat, muscle, bone mass and fluid.

For this book’s purposes it is the body fat and muscle mass that interests us. They are usually reported as relative measures, such as body fat percentage. Elite endurance athletes can have body fat as low as 4 or 5 per cent for men, or 8 per cent for women; for the rest of us, a normal healthy range is between 10 and 20 per cent for men and 16 to 30 per cent for women. The lower end of each would be a more athletic physique.

There are many different techniques for measuring body composition, many of which sound suitably sci-fi, and all have their pros and cons. In sport we sometimes use DEXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) scanning, which hospitals use for measuring bone density (which we’ll return to in Chapter 15, Ageing); this has the lowest margin of error. A big con of using this technique yourself is that it will likely involve paying for a private clinic – you’re unlikely to find one of the machines at your local gym – and there is also the fact that it involves a small radiation dose, so wouldn’t be suitable for everyone.

At the other end of the spectrum, skin fold measurements (anthropometry), which involves having your skin pinched with callipers (by an appropriately trained professional!), can be a reliable tool to assess meaningful change.

If you do have access to either of these methods, make sure you use the same method each time (even down to having the same person pinch your skin) so that you’re comparing like with like, rather than using two different methods, which can increase the rate of error.

For the rest of us without access to body composition machines, it’s time to dust off the tape measure and scales, and use our weight (as part of a combined approach, rather than on its own), waist size and our own eyes as our home body-composition assessment.

You should weigh yourself once a week, before breakfast. One of the biggest sources of demotivation I see is when clients weigh themselves each day – or worse, more than once a day. If you are a boxer or MMA fighter making weight leading into a fight, it can be justified to track small changes – but for everyone else, don’t bother. It isn’t going to monitor anything meaningful and it is more likely that it will induce stress as you constantly analyse any fluctuations in your weight.

Here’s why your body weight can change so drastically from one day to another:

Hydration status: a 1 per cent loss in fluid equates to 1 kg in body weight (that’s 0.75 kg for a 75 kg person) and can result from walking around for an afternoon and forgetting to drink fluids. As highlighted in Part I, when you start to exercise and sweat loss increases, it isn’t uncommon for dehydration to increase above 2 per cent (1.5 kg for the 75 kg person). In women, the menstrual cycle can also affect fluid balance.

Carbohydrate storage: the fuel in the tank (stored as glycogen) actually binds with water too. With an average of 500 grams of glycogen (in liver and muscles), each gram binds with 3 grams of water so that, when fully fuelled, there is around 1.5 kg of water (depending on the size of the person). This explains some of the immediate losses made when someone starts a low-carb diet.

Gut feeling: waste products stored in the intestines before removal may add up to as much as 300–700 g to your weight, depending on your size. Low-fibre diets (called in this context low-residue diets) are used clinically (in hospitals before operations) and in sport (pre-competition) to reduce undigested residue in the gut.

Muscle growth: muscle tissue takes longer to build, so it takes longer to add 2 kg of muscle than to lose 2 kg of body fat. If you are training a lot, it is very common for lean mass to increase, especially early in a training programme – this often makes it feel like your weight is staying the same, even though body fat is reducing and muscle mass is increasing.

So instead of concentrating on your weight, think about your body composition. After all, it’s the changes in both muscle mass and body fat that will help you perform better in training, look better in your clothes and improve your health long-term.

The next step is to measure your waist. As with weighing yourself, measuring your waist daily is pointless; you aren’t going to see any changes overnight. Check once a month instead. This is how often we check body composition with our elite athletes and performers and it means there is time to see meaningful change. I’d recommend the same for when doing this at home – then put the tape measure away, along with the scales.

And, while this might seem like a simple piece of advice, not everyone measures the right part of their body. So, to be clear, to measure your waist:

As a bit of a health warning, measuring your waist can give you some insight into whether you’re storing visceral fat (the more dangerous, active fat). So regardless of your height or BMI, you should try to reduce your body fat (lose weight) if your waist is 94 cm (37 inches) or more for men, or 80 cm (31.5 inches) or more for women2, and you should see your GP if your waist is 102 cm (40 inches) or more for men, or 88 cm (34 inches) or more for women.

This method isn’t measurable in quite the same way, but it’s still a reliable indicator that you’re making progress. Every week ask yourself how your clothes are fitting. If your goal involves losing weight, then ask yourself if your trousers are feeling any looser round the waist, or if your shirts or tops feel any baggier. If you’re trying to build muscle, are your trousers feeling any tighter around the mid-thigh? Shirts or tops pinching more at the chest, shoulders or upper arms? It might be subjective and lacking hard data, but often you’ll feel these things as they start to happen – and that can be a more satisfying result than analysing any quantity of numbers. Use a trusted friend as a barometer – and not someone who discusses weight loss as a daily greeting. These guides, alongside weight and circumference, can form your home body composition assessment, and demonstrate you are moving in the right direction.

But as we’ve discussed throughout the book so far, changes to body composition are only part of the answer. What about how you feel each day?

In Olympic sport, whether it’s a judoka or a boxer making weight before the Olympic Games, a sprinter training to improve strength and power or a long-distance runner aiming to improve endurance, it is vital to know how athletes are responding to training (and life). This is also an essential piece of knowledge within football; with Arsenal Football Club and most international teams I have worked with, we regularly use wellness questions, in which we ask athletes to rate how they are feeling in terms of mood, energy levels, sleep quality and other key questions, on a sliding scale of 1 to 5, to gauge how the athlete is coping.

It’s important to keep the burden low, and these questions have been refined from longer research-based questionnaires and some specific points relevant to the field added in. In each of our examples above, the athlete will see changes in their energy levels, mood, sleep, appetite and soreness as their training programme changes from week to week.

We would use these questions on players every day over a prolonged period of time to establish their baseline, and then look for any fluctuations that might demand an intervention. So, an easy one to spot would be a player who normally scores between 3 and 4 on his energy levels, but comes in the morning after a match and reports a 1. It’s a trigger for a further conversation with that player to try to work out the underlying issue (how was his training the day before? Is his nutrition on plan with fuelling and recovery?).

This is exactly the same for you and your training and nutrition. As you start to tailor your nutrition to support your training and work schedule, you will start to see patterns emerging that you can act upon.

Now, I know what you might be thinking: in a world full of fantastic science and technology, with the bottomless resources of an organisation like a Premier League football club, why would we use something as soft as a questionnaire? And the answer is simply that it is scientific.

A recent systematic review (that is, one that is drawn from the peak of the evidence-based research that we will discuss more fully in Chapter 14, Supplementation)3 concluded that ‘subjective self-reported measures trump commonly used objective measures’, which leaves little for me to add.

It’s easy to forget that ultimately these are people we’re dealing with, not machines with binary outcomes. Yes, we use the questionnaire as a first line and we can and do use data to further investigate and validate things, but no one knows better than you how your energy levels are.

So, when it comes to measuring your own progress with the Energy Plan, a wellness questionnaire might well be the best tool you have at your disposal, just as it is for the athletes I work with.

When using this questionnaire to self-monitor, you need to establish your baseline. Use the first couple of weeks to assess where you normally sit on each of the scale, – doing it every day, at least for the first couple of weeks, will help you establish that – so that you have a guide to see when you fall out of your norm; for example you might be affected by extra stressors around travel, work schedule or life stress (which we cover in Part III), and when you might need to adapt your training or nutrition to help. It will also enable you to look back over time and see how your plan has positively impacted on these areas of your life and not just on how your body looks.

Once you have established your baseline, use the questionnaire once a week to see how you are feeling in the key areas. This is during your weekly check-in, as outlined below.

Use the questionnaire daily, like the athletes I work with. Unlike checking your weight, checking in on how you’re feeling isn’t something that will inhibit your progress. But it’s important to do it at the same time each day.

When I was working with Olympic athletes or footballers within a training venue every day, I was able to see them regularly to look at how their Energy Plan could be refined to meet their goals.

Football players are always busy with their various commitments, so sometimes we would have to be more creative on where we would catch up. In the gym, the restaurant, or I actually had one of my most productive consultations with Arsenal forward Alexis Sánchez in the sauna, discussing recovery nutrition following a match. This may sound extreme, but the point is that we needed to find time in his schedule for a check-in about his nutrition; you need to make time in your schedule to check in about yours.

One of the most common issues I faced outside of sport is that the people I worked with wouldn’t spend any structured time reflecting on the previous week and planning for the week ahead. This meant that the good behaviours established in week 1 would be a distant memory when I next saw them, after a few busy weeks.

So I introduced the weekly ‘check-in’. Make no mistake about it, this is the glue that binds your Energy Plan together.

Most Olympic athletes would keep a training diary (despite the wealth of technology at everyone’s disposal, usually just a paper diary) in which they could add notes on their training, nutrition, how they were feeling, including wellness tracking scores. So this is what I recreate now with my clients.

As a bare minimum for the busy, you need to check in once a week. This means protecting time on your calendar (just like for your training), but you could do it on the train in to work or if you get a spare 15 minutes to sit and do it in your local café at the weekend (this seems a natural time to check in). You can use the chart here as a template:

●How do you feel?

●How were your wellness scores over the last week?

●What worked well?

●What changes have you successfully made, such as consistent lunches or an extra training session?

●When did you deviate from the Plan and why? This can help you understand the things that affected your Energy Plan, maybe a work deadline or a friend’s birthday.

What do you need to plan for the week ahead that will affect your Energy Plan? Work trip? Social engagements?

What do you need to execute your Energy Plan: are your exercise classes booked? When will you do the shopping? (see Chapter 10, From Plan to Plate).

The Borg scale (also known as the RPE (rating of perceived exertion) scale) was created in the 1960s and has been used widely in sport ever since. The original was on a 6–20 point scale; a ‘modified RPE scale’ (0–10) has since been developed and is widely used in professional sport and health and performance clinics. The scale measures how hard you find a training session and can be a guide for a trainer on whether it is too easy or too difficult. In this case, we are using the scale to see how you feel (how much energy you have) during training after eating different meals (or performance plates).

Monitoring how you feel during training (just like you do with your wellness tracking outside of training) is a way to assess how your Energy Plan is working. For example, thinking about the same session each week (such as your exercise class on a Saturday morning), how do you feel after a fuelling meal compared to when you are training low? How hard does training feel when you have had a flat white an hour before the sessions compared to when you haven’t?

You don’t need to do this every session like an elite athlete. This is a tool for you to use during your training week. When you are making changes to your Energy Plan around your training it’s another marker to help show yourself that you are moving in the right direction.

| Rating | Description |

| 0 | Rest |

| 1 | Very, very easy |

| 2 | Easy |

| 3 | Moderate |

| 4 | Somewhat hard |

| 5 | Hard |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Very hard |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | Maximal |

In Part I we outlined that sweat rates per hour vary greatly between individuals, even during the same training sessions. Each one of our three sporting examples from the beginning of Chapter 4 will use this calculation to understand their individual sweat losses, and then personalise their drinking behaviours to minimise dehydration in both hot conditions (such as warm weather training camp) and cool (autumn and winter fixtures).

This should be the same for you, whether you are planning to run your first marathon or are just interested in how much you sweat during that intense HIIT session at the gym. Thirst is an important physiological cue to drink, but it doesn’t provide the full picture on the level of dehydration.

Check your urine colour and volume, particularly pre- and post-workout. You can refer back to the section ‘Water’ at the end of Chapter 2 for more guidance.

To calculate your own sweat loss, weigh yourself before exercising, making sure you are wearing minimal clothes. Then weigh yourself again after exercising, wearing the same amount of clothing. This gives you a broad measure of sweat loss, and you should then aim to replace 150 per cent of these losses. So, for example, if you have lost half a kilo during the course of your training, you should aim to drink three-quarters of a litre of fluid. This can be useful as a guide if you’re worried you’re drinking too little or too much around training.

If you wanted to take this further still, you could calculate your percentage dehydration. In sport, we do this because of the decline in performance significant sweat losses cause. Anything over 2 per cent would be cause for concern as it can reduce physical and cognitive function; that would be, for a 70 kg person, 1.4 litres of sweat loss.

You might wonder why, given that one of the principles of the Energy Plan involves achieving balance between your energy in and energy out, none of the monitoring involves counting your calories in and calories out.

Firstly, it’s important to realise that much of the available data for calories in and out, the kind that is usually tracked by a wearable fitness device (or one on your phone), contains a lot of error – as much as 25 per cent when it comes to calculating energy out6 – and the margin of error when recording intake can be as low as 2 per cent and as much as a whopping 59 per cent – a huge variability.7

Whether you’re calculating your energy out with a fitness tracker or your energy in with a mobile tracker, it’s important to realise that they’re just estimates. They will contain error. They can be useful to give you a ballpark figure as to whether you’re eating or moving more, but if you’re doing too much maths around them, it might be an idea to call time on them.

I don’t want you to be fastidiously photographing every morsel in your food diary, or frantically calculating calorie consumption on your calculator. Your energy will be better spent elsewhere. With all of our athletes, performers and businesspeople, results are created by getting the core principles right at each meal, each day, each week and monitoring the outcomes (with the wellness tracking and body composition described above).

As we’ve discussed before, looking at calories as your fuel budget for the day is a useful guide, but eating to an energy budget without focusing on the fuel composition can lead to insufficiency in some of the nutrients and micronutrients your body needs to function optimally. It’s much more important to meet the targets of key fuels that the body requires, using the planners in Chapter 6. Remember the principle of the TTA model that we looked at here: the type of food (its nutrition content, whether its role is fuelling or maintenance), the timing of the food (how close to training?) and the amount (portion size at each meal, and over the day). Because it’s only through these that you can learn to achieve the sustained peaks and reduced troughs that we will tackle in the next chapter.

HOW DO YOU KNOW IF YOU ARE ‘MOVING THE NEEDLE’?

The seven signs are:

| 1. | You have more energy Feel more energetic throughout the day Less reliant on caffeine |

| 2. | You sleep better Get to sleep quicker and have better sleep quality Feel more refreshed upon waking |

| 3. | You’re in a better mood Feeling happier and more positive |

| 4. | You feel satisfied after eating Not ‘full’ after eating Or hungry all of the time |

| 5. | Clothes fit differently Either a bit looser (fat loss) Or a bit tighter (muscle gain) |

| 6. | Fitness has improved You feel stronger during your training sessions (lower RPE) Improved fitness in aerobic sessions Lifting more weight in the gym |

| 7. | The bottom line – more productive Better in training Better at work Better at home |