10

A HEATED CONTROVERSY as to whether Monaco should be allowed to be represented at the Great Exhibition to open in Paris on April 1, 1867, brought Albert into confrontation with Louis Napoleon. Inside the Exhibition’s focal point, a “vast elliptical building of glass 482 metres long, set in a filigree of ironwork, not unlike London’s own Crystal Palace,” the nations of the world were to exhibit their finest recent achievements. Although the Emperor had never publicly condemned the Casino, he did not feel its gaming rooms should be promoted in an exposition at which England’s Baron Joseph Lister introduced the principle of antisepsis, Sweden’s Alfred Nobel displayed his newly invented dynamite and room had been made for Herr Krupp of Essen’s new weapon, the largest cannon—an immense fifty-ton gun—the world had ever seen. Albert disagreed. In the end Monaco was given space to display a newly designed portable cabana and exotic plants from its gardens in an outside pavilion where for fifty centimes you could see the works of controversial artists like Courbet and Manet, also excluded from the inner sanctum of the main building.

Albert was a determined young man. An only child, his mother dead, his father blind, he had turned to his grandmother for understanding and affection. They were both strong-willed, opinionated, and often clashed head-on. Yet each retained a forceful hold on the other. During his mother’s long illness from 1862 and 1864, Albert had boarded at the Stanislas College in Paris and then went on to continue his education at Mesmin, a Catholic university near Orléans. On the grounds there one afternoon, he threw a stone pebble that missed its mark and blinded a young man who was studying to enter the church. An acrimonious lawsuit followed, and the young man who was blinded, I. Yvonneau, was awarded 12,000 francs, costs of the suit and an annual pension for life of 1,200 francs. It was directly after this tragic episode that Princesse Caroline tried to affiance Albert to Queen Victoria’s cousin. When this failed (the school incident did not seem to have a direct bearing), she suggested that he come to Monaco and oversee their business interests in the Société des Bains de Mer (now referred to as the S.B.M.), which included not only the Casino, but the Hôtel de Paris, Café de Paris, the Sporting Club and large tracts of Grimaldi-owned land that encompassed about 15 percent of the Principality and was being developed into villas. Albert at first rejected this proposal, finally agreeing after much pressure from his grandmother to do so. With Charles blind and ailing, Caroline was again in control of the Grimaldis’ business interests. Her age made this a difficult burden and she hoped that Albert could be groomed to take over her responsibilities. The young man, however, had no aptitude for or interest in business.

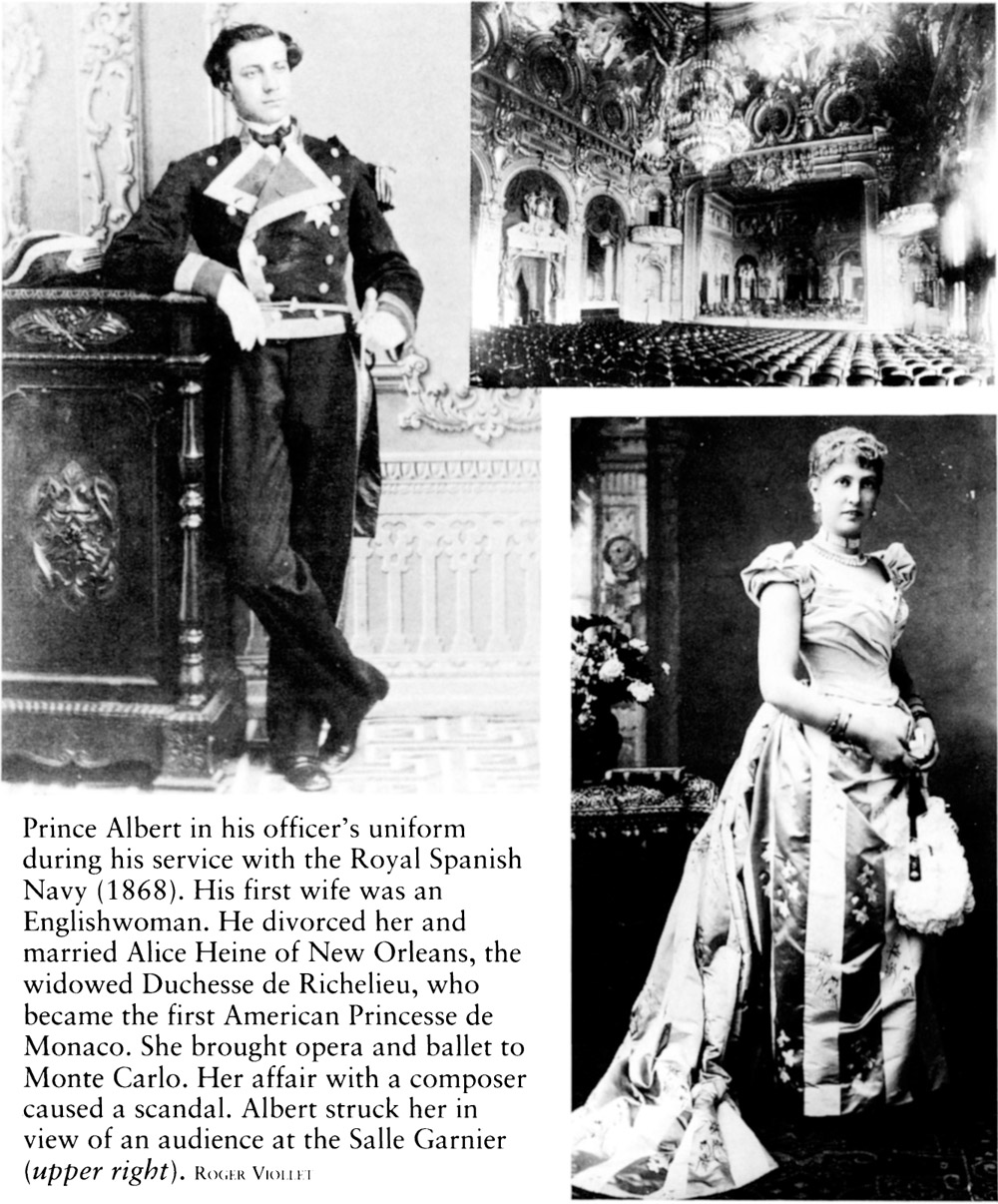

Since his childhood Albert’s abiding preoccupation had been the sea, his ambition to create a Monégasque Navy that he could command. France would never have agreed to such a warlike enterprise, but Albert pressed forward in preparation for what he thought was to be his calling. To Caroline’s distress, after six months in Monaco, he entered the French naval academy at Lorient, at which he did brilliantly. In 1866, in a surprise move, he joined the Spanish Navy, presumably in rebellious pique.

His choice was ill-conceived. Spain was undergoing turbulent times. Isabella II’s rule had been one of party conflicts among moderates and progressives who favored a constitutional monarchy and the extreme reactionaries who did not. The conflict culminated in armed rebellion and insurrection. Good soldiers loyal to the Crown were at a premium. Albert rose swiftly from midshipman to lieutenant, but with conditions as shaky as they were in Spain, he resigned from the navy after two years. On March 1, 1868, Isabella having been deposed and replaced by a constitutional monarchy with Amadeus, Duke of Aosta, as King, he embarked from Verona for a voyage to the United States on a “magnificent frigate” under the command of Captain Don Francisco Navarro. A former lieutenant in the Spanish Navy, Simon de Manzanos, was hired by Albert’s father as equerry and watchdog. Manzanos wrote the Prince de Monaco almost daily detailed reports of his son’s adventures.

Two months later, they arrived in New York, where they stayed at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, having stopped at Havana and various other ports on the way. It was not easy to elude Manzanos, but Albert managed several evenings on his own with a young Spanish officer. He saw a bit of New York’s night life and met a few young, attractive American women. His whirlwind American tour included visits to Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Chicago, Louisville, Cleveland, Buffalo, Niagara Falls, Montréal, Québec, Gorham, Boston, Springfield, Westport and back to New York, where on July 2 he boarded L’Aigle for the return voyage. Québec and the Indian country (where he purchased “curios of Indian industry for 340 francs!”) appeared to interest him the most.

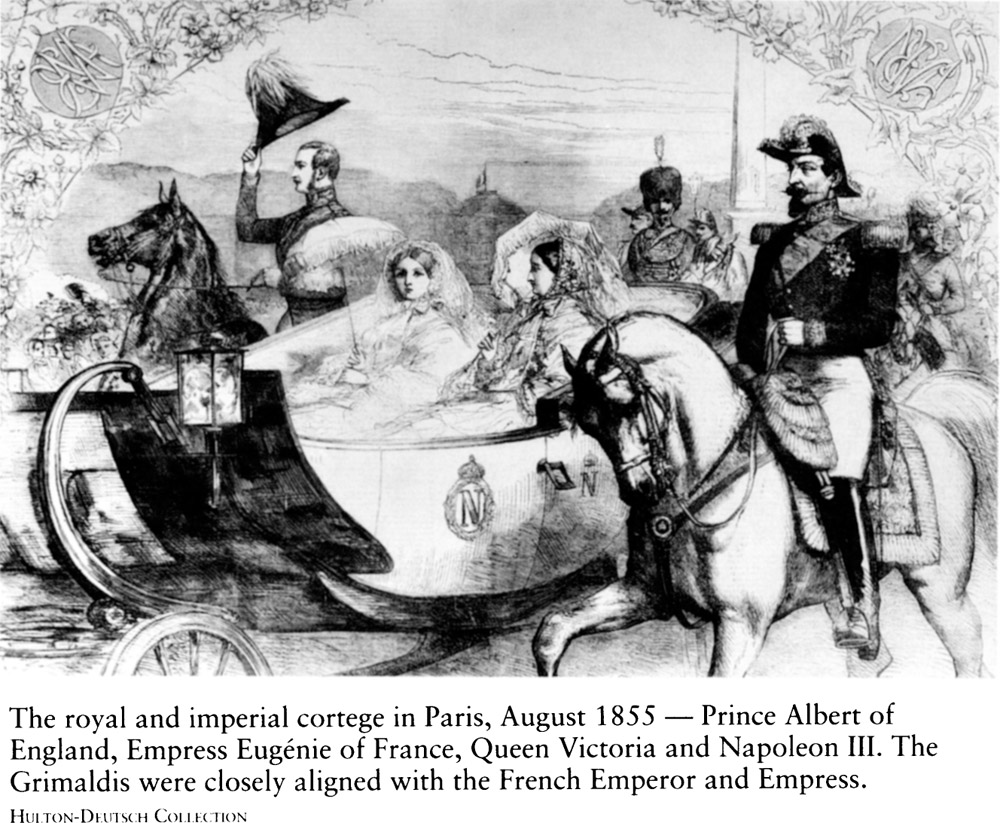

Princesse Caroline had not been idle during this time. Still determined that her grandson should marry into the British royal family, she sought Louis Napoleon’s aid in selecting a suitable prospective bride. The Emperor did not mince his words. The very conservative Victoria would never grant permission to a marriage between a relation of hers and the future sovereign of a state that was supported by gambling. However, Louis Napoleon had another suggestion.

He was extremely fond of the attractive young Lady Mary Victoria Douglas Hamilton, the daughter of the late 11th Duke of Hamilton and Princess Marie of Baden, who was the Emperor’s second cousin. The Hamiltons were very rich and had homes in Scotland, Paris and Baden. The present 12th Duke of Hamilton, Lady Mary Victoria’s older brother, was a well-liked member of the Emperor’s Court. An alliance with the family would mean that the Grimaldis would be related, albeit distantly, to the Emperor. Princesse Caroline could hardly refuse such a union. Albert, just turned twenty-one, was not at all certain he wanted to marry Lady Mary Victoria, or anyone else for that matter. To his grandmother’s consternation and Louis Napoleon’s displeasure, he bought a small yacht named the Isabelle, and with his aide-de-camp, Captain de Journal, and four seamen, and acting as his own navigator, he sailed off on a three-month cruise down the coast of Africa and so was incommunicado.

Lady Mary Victoria was equally unenthusiastic about the prospect of an alliance. Had she and Albert met, they would at least have been assured of the attractiveness of their proposed future spouses. Albert cut a striking figure in uniform—tall, broad-shouldered, his dark eyes well set in a strong, robust face. Lady Mary Victoria was a Scots-English beauty, with clear blue eyes and golden hair that fell in natural ringlets about her fair face. A lively young woman, she loved horses, clothes and dancing, and adored her bachelor brother “Willie,” the Duke of Hamilton, who was six years her senior and who protected and spoiled her, and squired her to the finest homes in Paris. Willie owned a prestigious racing stable and brother and sister were often seen at the races where the press described her stylish attire in glowing prose.

Albert returned from his “runaway” voyage in July 1869, somewhat chastened. The Isabelle had met with severe storms and had been buffeted by high waves, unable to come into the harbor at Monaco for nearly a week and with little to eat on board except for some hard biscuits. He was greeted by Princesse Caroline and the Duc de Bassano, a representative of the Emperor. A few days later Albert was in Paris and a marriage contract was being drawn that included a dowry of 800,000 francs. Willie had presumably convinced his sister of the importance of pleasing Louis Napoleon.

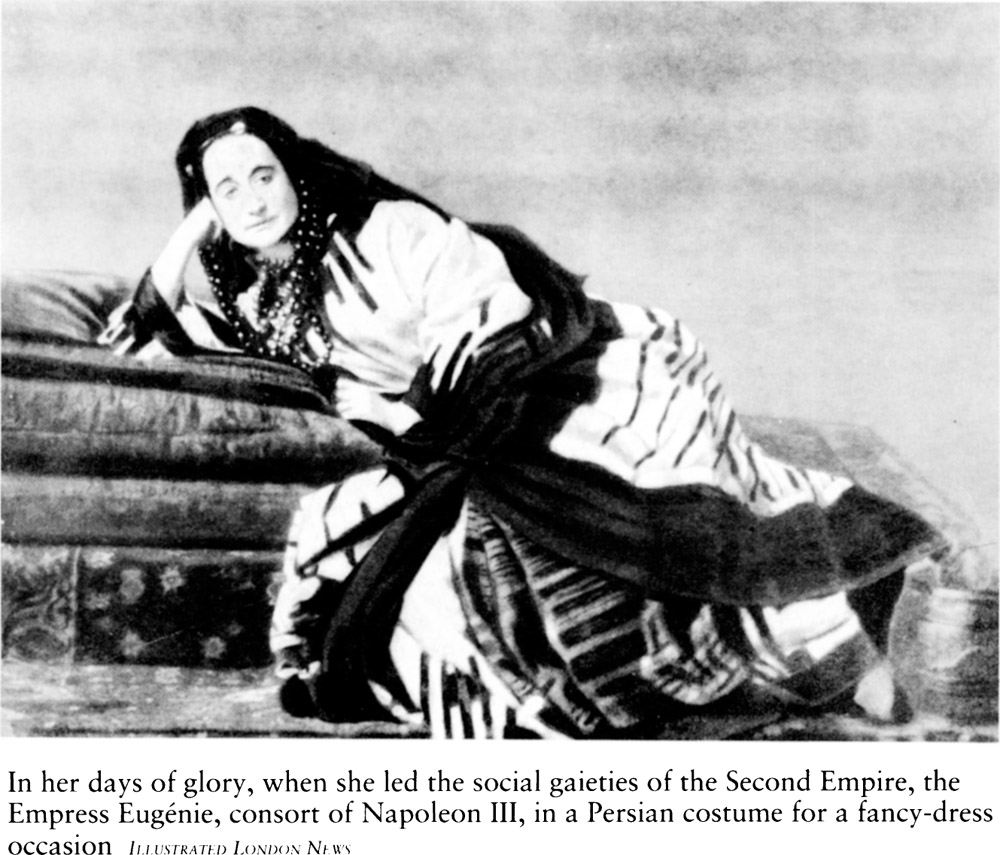

With the glittering triumph of the Great Exhibition and the unprecedented lavishness of the Tuileries Balls, the Second Empire had reached a peak of splendor. Its society seemed eager to follow the paths indicated by its pleasure-loving Emperor, seeking consciously to recapture the indulgences of Louis XV. The plumed hats and gowns of that era had returned to style. Masked balls were given so frequently that the Paris haut monde appeared to be attending a nonstop carnival of peacock extravagance.

“A procession of four crocodiles and ten ravishing handmaidens covered in jewels preceded a chariot in which was seated Princess Korsakow en sauvage,” Anthony Peat, an English guest at one ball reported. “Next came Africa, Mademoiselle de Sèvres mounted on a camel fresh from the deserts of the Jardin des Plantes, and accompanied by attendants in enormous black woolly wigs; finally America, a lovely blonde, reclined in a hammock swung between banana trees, each carried by negroes and escorted by Red Indians and their squaws. There were three thousand guests and it is said the cost of this one ball was four million francs.”

Women at these balls “emphasized their bosoms to the limits of decency (sometimes beyond).” While the Second Empire was at its pinnacle, its morals had sunk to greater depths than in the time of Louis XV. The sixty-year-old Louis Napoleon had a ravishing nineteen-year-old mistress, the Comtesse de Castiglione, to whom he gave a 422,000-franc pearl necklace and a 50,000-franc monthly allowance. (England’s Lord Hertford, “by reputation the meanest man in Paris, gave her a million for the pleasures of one night in which she promised to abandon herself to every known volupté. Afterwards, it was said, she was confined to bed for three days,” Mr. Peat comments.)

The haut monde of Paris was overflowing with grandes horizontales. Prostitution and syphilis were rampant. Many of the great men of the age died of syphilis, which was then incurable, including Manet, de Maupassant, Dumas fils and Baudelaire. Renoir was to write that he could not be a genius because he alone had not caught the disease. As one historian noted, “The terrible disease was symptomatic of the whole Second Empire, on the surface, all gaiety and light; below, sombre purulence, decay, and ultimately death.”

The premature aging of the Emperor was no doubt brought on by his debauchery. In 1869 he became painfully ill with a progressively worsening liver condition and hopelessly bewildered by foreign and domestic events. His greatest miscalculation was based on his firsthand knowledge of that “deadliest of all French diseases,” l’ennui. He believed France had to be distracted, and so he went in pursuit of la gloire. At home fortunes were spent to rebuild a glorious Paris. Gigantic exhibitions were held. Money raised through high taxation had financed his excesses and his failed foreign designs and his subjects grew more and more restless.

“If [the Emperor] uses his influence to favor a reactionary clerical policy,” his outspoken nephew Prince Napoleon wrote in a memo, “if he continues to employ discredited and unpopular men like the present ministry, he may secure a passing success, he may dominate the country for a time, but he will be strengthening the republic, socialist and revolutionary Opposition of the future; and this new power given to it will be terribly dangerous when any crisis occurs at home or abroad.”

Louis Napoleon was not unaware of the precariousness of his reign. To save the throne for his son, he was planning to convert the regime into a “Liberal Empire” and himself into a constitutional monarch. But it was already too late. With economic conditions worsening daily, unemployment high, and inflation the highest in years, the glory of the Emperor was fast fading, and Louis Napoleon, at a loss at what to do to restore his prestige was a confused and weary man. The Illustrated London News, covering the drill of French troops, wrote that “the Emperor huddled in his seat, was a very minor show, whereas the Empress struck a splendid figure, straight as a dart.” Eugénie’s powers rose as the Emperor’s declined. She had told a member of the Court that if another revolution came, “she would know how to save the crown for her son and show what it meant to be an Empress.” One faithful admirer added: “There is no longer an Eugénie, there is only an Empress.”

Cold, capricious and aggressive, Eugénie dominated her husband and the Court; and once she had decided that Albert and Lady Mary Victoria should wed, there was no doubt about the matter. On a warm August night, the young couple met at the Tuileries at one of the magnificent masked balls in which Eugénie excelled. The Empress was dressed as Marie Antoinette, whom she greatly admired; Lady Mary Victoria came as Juliet, and Albert, complete with patch over one eye, was Lord Nelson. Strings of electric light rimmed the gardens and the dance floor; water cascaded over stucco rocks from specially constructed fountains. Despite the romantic ambience, “Juliet” reported that “Lord Nelson” indeed danced like a sailor; and the sailor—although dazzled with Juliet’s charms—found her somewhat empty-headed.

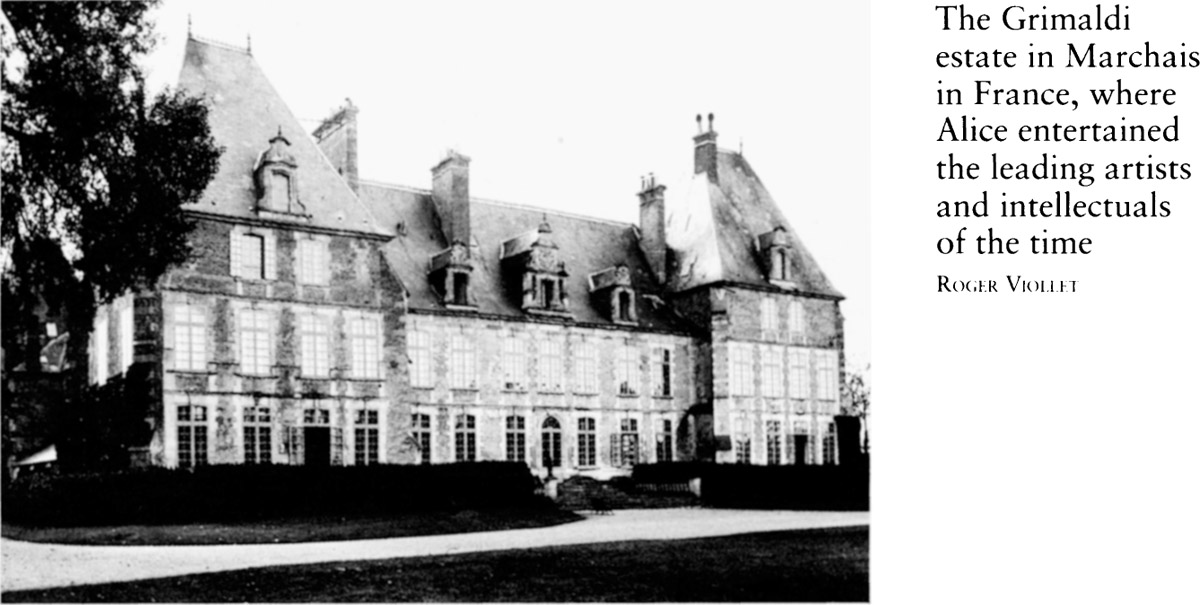

The wedding, to be solemnized at the Grimaldis’ private chapel at the Château Marchais on Tuesday, September 21, was to have been attended by the Emperor and Empress. As the date approached, Louis Napoleon took ill and was confined to bed. The Duc de Bassano was once again designated to be his representative. The betrothed couple might have been disappointed at this, but the bride’s gifts from the two monarchs made up for some part of it. She received a superb emerald and brilliant bracelet, a diamond brooch in the shape of a thistle (for Scotland) and a suite of sapphires—a necklace, bracelet and earrings.

From her mother the young bride received a magnificent necklace of six rows of large, fine pearls with an emerald and diamond clasp and a fringe necklace containing 1,200 brilliants, a tiara of 44 large brilliants and a diamond and pearl tiara; from the Duke of Hamilton a rivière of emeralds and diamonds and “matchless” pearl earrings and a large diamond pendant in the shape of a star. Albert had made himself a very rich catch. And the bride?

“The daughter of our Scotch duke will become a sovereign princess,” an Edinburgh newspaper reported. “Her future kingdom, it is true, is scarcely as extensive as is one of her brother’s estates, but, nevertheless, the Principality has maintained its independence for many centuries. The fair and amiable Lady Hamilton is the Emperor’s cousin.”

Monaco was of modest size, but the Grimaldis had greatly enhanced their wealth. The Casino at Monte Carlo had brought them a huge sum of money in the past few years, and Princesse Caroline made sure that the château at Marchais would reflect their new position. For the wedding celebrations she refurbished the guests’ rooms and offered dancing, concerts, racing and shooting for entertainment. The extensive grounds were decorated with colored lanterns, streamers and flags. A pavilion was erected for the dancing and a waltz band brought all the way from Vienna. In the evening there was a magnificent display of fireworks. And the marriage feast was of unprecedented splendor, even when compared to those at the Tuileries Balls.

Albert looked exceptionally handsome in his marine-blue officer’s uniform, and the bride strikingly beautiful in an elegant white satin gown, designed by Worth, a white tulle veil enveloping her figure like a gentle sea spray, her train a startling sixteen feet long. Her long, blond hair was drawn back from her face by a pearl tiara, and about her neck were the six rows of pearls her mother had given her as a wedding gift. A fortune had been spent on her wardrobe, made by the top Parisian designers; her jewels (except for the gifts of the Emperor and Empress) had all come from Queen Victoria’s jewelers in London.

In the course of her wedding day she changed costumes three times. For the signing of the marriage contract she was sweet and virginal in pink poult-de-soie, a demi-train looped at the sides, a pink silk pouf added at the skirt just below the waist. After the wedding ceremony, performed by the Bishop of Soissons, she changed into a brilliant lapis-lazuli blue gown, trimmed with velvet and fringe to match.

Her wedding trousseau was described in all the leading fashion columns and magazines, including The Queen, which went into description of a second traveling dress “made of shot green and mauve satin. The redingote has a train at the back which is made up à la réactionnaire.” The writer went on to describe four ball gowns “in the style of the Court dresses worn during Louis XV’s reign—all exceedingly original and in capital taste.”

Albert had married a young woman who was not only rich but a fashion plate. The new Duchesse de Valentinois was also strong-willed and could be petulant if she did not get her way. Disappointed that the Emperor and Empress had not attended their wedding, she decided she would “rather die than miss” the grand social event of the season—the Paris Autumn Races, which had been convened six days after the wedding. And so the honeymoon was postponed.

The sun shone that day, although the weather had been bitter cold for a week. Louis Napoleon was driven up to the imperial stand and stepped out of his carriage with surprising spirit, Eugénie, elegantly attired in green and black velvet, on his arm. Albert, Mary Victoria and the Duke of Hamilton were guests in the Royal Enclosure, and from there they watched Willie’s horse, Capitaliste, win the Prix de St. Cloud. In the press coverage of this event, it was noted that because of the recent death of the Grand Duke of Hesse-Homburg, the number of European sovereigns had been reduced to forty: “five Emperors, one Sultan, one Pope, ten Kings, two Queens, six Grand Dukes, five Dukes, and ten Princes [including the Prince de Monaco].” The following Sunday, the weather not nearly so bright, the newlyweds watched Capitalist run the four-mile Prix de Gladiateur and win in the Hamilton colors once again.

Unlike his father and his late uncles, Albert did not thrive on Parisian social or Court life. Nor was he attracted to the sexual promiscuity of the times. While his young wife positively glowed as she attended races and galas in her extravagant wardrobe and dazzled the crowds with her newly acquired jewels, Albert yearned to be back at sea. Attractive as Mary Victoria was, he found little to share with her and described her in a letter to his former equerry Simon de Manzanos as being “sadly deficient in even the most basic of common knowledge.”

Albert was developing into something of an intellectual. During his three-month journey on the Isabelle his interest in the sea had broadened from the intense pleasure he gained from navigation to sea life itself, and he had recently taken up the study of oceanography in a serious way. When, finally, the newlyweds departed for a honeymoon in Baden-Baden (accompanied by the bride’s mother, Princess Marie of Baden, the Dowager Duchess of Hamilton), Albert packed several heavy tomes on the subject, while Mary Victoria brought along her fabulous “Louis XV” ball gowns.

Baden-Baden, in the Black Forest, had been one of Europe’s most fashionable spas ever since the Casino had been built in 1824. The Grand Duke of Baden was the Dowager Duchess’s father, and the family had a magnificent castle there. Despite what promised to be an enjoyable honeymoon, difficult times developed; for during the winter of 1869, relations between France and Prussia had reached an impasse. Baden was an independent state, surrounded by thirteen Prussian provinces; and if there was war between France and Prussia, the small state had little choice but to ally itself with Prussia.

The newlyweds and the bride’s mother arrived in Baden-Baden at the end of October. The weather was foul and the season nearly over. Dinner conversation was gloomily directed to the growing hostility between France and Prussia and what a war between the two great countries would mean.

For two centuries Prussia had been building a strong state by means of a disciplined army and a civil service drilled in political theory, law, economics, history and penology. So powerful did Prussia become that it survived both military defeat by Napoleon in 1807 and the revolutionary surge of 1848. Now William I, King of Prussia, and his appointed Minister-President, Otto, Count von Bismarck, were determined to unite the German states in an empire under Prussian hegemony. The Grand Duke of Baden did not relish such an eventuality, which would eclipse what little power he had. And besides, he had always remained on the best of terms with his wife’s cousin, Louis Napoleon.

A heavy cloud of anxiety hung over Baden-Baden during the somber month of November. Mary Victoria discovered she was pregnant and took to her bed with a violent case of morning sickness while Albert closeted himself with his oceanic tomes.

It was decided that the young couple and the Dowager Duchess should leave for Monaco and remain there for the birth of the child, due the following summer. They arrived in Geneva by coach “with a numerous suite” on December 2 and repaired to the Hôtel des Bergues where they were to spend the night before continuing on to Nice. A fierce thunderstorm struck just as they were preparing to depart, followed by torrential rain, hailstones and heavy snow, which delayed the party another three days. They arrived in Nice just in time for a devastating mistral that ripped trees from the earth. The next day, the weather calmer, they entrained for Monaco, where they were given a tumultuous welcome. But any pleasure this may have generated was short-lived.

No one had prepared the bride for the gloom that awaited her in the Palace. Not only was her father-in-law blind and short-tempered, the Palace was in mourning. Albert’s aunt Florestine, the Duchess of Urach, still mourning the recent death of her husband, dressed in flowing layers of black and wandered about the Palace like a bird of night, dominating the household. To add to the problems with which Mary Victoria was faced, Princesse Caroline arrived and there were ferocious quarrels between her and her bereaved daughter over who had the final say in the running of the Palace.

Albert’s marriage difficulties reached a climax in the last week of January 1870, when the Dowager Duchess prepared to return to Baden-Baden. Mary Victoria decided that she would leave, too. Husband and wife had not had much time alone. Albert had resented his mother-in-law’s constant presence and the conditions under which the bridal couple had begun married life had been stressful. Nonetheless, they did appear to be unusually ill-matched. Albert was not overly distraught when Mary Victoria departed, and he had refused to accompany her when that was proposed.

“My dear Mary,” Princesse Caroline wrote on February 5, 1870, while the bride and her mother rested in Nice before the long journey home. “My grandson’s grief has so saddened me that I’m writing direct to you to make an appeal to your heart. Can you not forgive Albert for what you reproach him with [i.e., not being attentive enough]? The tender love you have aroused in him will give him the strength to change his ways, he has assured me, and to do all he can to make you happy. . . . I’m sure that for your part, my dear Mary, you must feel that a wife is the link of her family. . . .”

Two days later, still in Nice, Mary Victoria replied: “My dear grandmother. I was greatly touched by your letter, and I thank you for all its affection for me. The best memory I have of the recent sad time is the kindness you showed towards me. I am most grateful for this memory, which eases the bitterness of the weeks I spent at Monaco . . . .” On that note she left Nice with her mother and returned to Baden-Baden to await the birth of her child.

Instead of following her and perhaps effecting a reconciliation, Albert went to Paris where he met with the Emperor and Empress. They were shocked at Mary Victoria’s action but unable to do anything about it. “We should try to meet together, Mary and I, just by ourselves,” Albert wrote to his father on February 20, “but that’s the difficulty [implying that the Dowager Duchess never gave them any time to themselves].”

Within a few months war fever had consumed France. On Saturday, July 2, the Gazette de France announced that the throne of Spain, which had been vacant since 1868 and in dispute since that time, had been offered to, and accepted by, Prince Leopold of the house of Hohenzollern, with the consent of the King of Prussia. Nine days of anxious uncertainty followed. A letter was then dispatched by Louis Napoleon’s foreign minister to the King of Prussia’s emissary: “If the Prince of Hohenzollern’s renunciation is announced in 24 or 48 hours there will be peace for the moment. If not, there will be an immediate declaration of war against Prussia.”

Prince Leopold withdrew his acceptance of the Spanish Crown, but this was not enough of a guarantee for the Emperor or his foreign minister, the Due de Gramont. They wanted direct assurance from the King of Prussia that he would not authorize the candidacy afresh. This appeared to be a ploy. “It was too late to avoid war,” Eugénie was later to say. “You cannot imagine what an outburst of patriotism carried all France away at that moment. Even Paris, hitherto so hostile to the [Second] Empire, showed wonderful enthusiasm, confidence and resolution. Frantic crowds in the boulevards cried incessantly À Berlin! À Berlin!”

On July 19, war was officially declared by the Emperor. A week earlier, on July 12, 1870, Mary Victoria had given birth in Baden-Baden to a son who was christened Louis-Honoré-Charles-Antoine. Albert did not go to see his child, for on July 21, out of loyalty to France, he signed up with the French Navy and within two weeks was with the North Sea Fleet, ostensibly an enemy of his wife’s family.

11

LOUIS NAPOLEON WAS FACED with a war and a lack of funds with which to fight it. He turned for aid to A.&M. Heine, one of the largest banking houses in France. The concern was owned by two brothers, Armand and Michel Heine, who had made their fortunes as young men in New Orleans, Louisiana. Originally from Berlin and cousins to the great lyric poet Heinrich Heine, they had left Germany in 1840, disillusioned with its anti-Semitic and right-wing policies, for Paris, where their cousin was already established as a leading revolutionary literary figure. They went on in 1843 to New Orleans, a city dominated by Creole culture and where their second language, French, was spoken. The queen city of the Mississippi, New Orleans had been swept to fabulous heights as a port and market for cotton and slaves; and the Heine brothers, whose father had been a moneylender in Berlin, saw the opportunities.

With borrowed capital and, rumor had it, gambling winnings, they started a banking house. Within ten years they had become the most successful financiers in New Orleans and had fallen in love with the same young woman, the exotic and vivacious Amelie Miltenberger. Her father, born in New Orleans but of German heritage, was an influential cotton broker and her Creole mother had endowed her with extraordinary dark eyes and jet-black hair. Amelie, then twenty-one, chose the younger brother, Michel, who was four years her senior. Their wedding in 1853 was the great event of the city’s social calendar, held in the Miltenbergers’ lavish home and gardens and with a guest list that included New Orleans’s most glamorous and prestigious citizens.

A few months later, Michel and Amelie departed for Paris to open a European banking house, leaving Armand in charge of the brothers’ American interests. In an unusual partnership arrangement, for three months each year the brothers reversed their positions, and Amelie and Michel returned to New Orleans where they remained with Amelie’s family while Armand took over in Paris. Thus, Amelie and Michel’s three children, George (born in 1855), Alice (1857) and Henry (1860), were all born in New Orleans and held American citizenship. The death of the infant Henry and the advent of the Civil War sent the family back to Paris and ended the Heine brothers’ exchange of residences. By 1863, A.&M. Heine was one of the most powerful financial companies in France.

Part of the company’s success could be attributed to Amelie, whose Southern charm and unique beauty quickly made her a popular hostess, the belle of Louis Napoleon’s Court and the intimate friend of the Empress Eugénie. The royal couple even bestowed on the Heines the honor of becoming godparents to George and Alice. A clever administrator, Michel became not only exceptionally rich but powerful at Court and Napoleon’s trusted financial adviser. It was therefore not surprising that Napoleon should ask Michel Heine’s firm to float a loan to finance France’s war with Prussia. Amazingly, the Heines were able to raise the astronomical sum required within a matter of ten days.

The idea of war with Prussia continued to be enthusiastically received by the majority of the French population, none of whom doubted the outcome. What they overlooked was that Bismarck had succeeded in making France the aggressor, and that the southern German states would now join the north in resisting a foreign invasion. Although Monaco raised the tricolor beside the Monégasque flag in a show of support, and portraits of Albert in his French naval uniform appeared in the lobby of the Hôtel de Paris and in the windows of several shops, France had no real allies.

Thomas Carlyle in The Times wrote: “That noble, patient, deeply pious and solid Germany should at length be welded into a nation, and become Queen of the Continent, instead of vapouring, vainglorious, gesticulating, quarrelsome, restless and over-sensitive France seems to me the hopefullest public fact that has occurred in my time.”

It took six months for Paris to fall and nearly ten until peace was declared. As far as effective fighting went, the war was virtually over in six weeks. Albert’s ship, the Savoi, withdrew with the French fleet from the North Sea at that time. He was transferred to the Couronne and headed south in retreat to Calais. He had seen devastating action in the North Sea while on the Savoi, which had suffered heavy losses, but had come through unharmed.

The defeat of the French forces and the final surrender of Louis Napoleon to the Prussians were almost more than even Eugénie’s Castilian courage could endure. On September 2, 1870, the Emperor and 60,000 of his men were captured at Sedan, in the northeast of France. Louis Napoleon wrote to his wife: “I cannot tell you what I have suffered and am suffering. We made a march contrary to all the rules and to common sense: it was bound to lead to a catastrophe, and that is complete. I would rather have died than have witnessed such a disastrous capitulation, and yet, things being as they are, it was the only way of avoiding the slaughter of 60,000 men. . . . I have just seen the King [William, of Prussia]. There were tears in his eyes when he spoke of the sorrow I must be feeling. He has put at my disposal one of his châteaux near Hesse-Cassel. But what does it matter where I go? I am in despair. . . .”

The following day Eugénie was warned by the Prefect of Police not to remain at the Tuileries lest the crowds, which were already at the gates, force her to abdicate the Regency and do her harm. She consented to leave, the specter of her idol, Marie Antoinette, no doubt before her. With her at the time were Amelie Heine and a lady-in-waiting, Madame Lebreton. Amelie left the palace and went to her husband’s offices where arrangements were made for money to be transferred to England in Eugénie’s name, so that she could take refuge there. Meanwhile, Eugénie made her way with Madame Lebreton through secret passages to the Louvre and then out a rear door, after which the two women, dressed in concealing outerwear and carrying only one small satchel of clothes packed in a hurry, hailed a passing taxi, directing the driver to take them to the home of a known Loyalist. When no one answered their insistent knocks, they walked through milling, angry crowds, unrecognized, to the residence of another loyal friend, with the same result. Desperate, Eugénie remembered her American dentist, Dr. Evans, who lived on the Avenue Malakoff, and flagged down a second cab.

The women spent the night in Dr. Evans’s home while the good dentist, with the Heines and the Prefect of Police, made all the arrangements for Eugénie’s getaway. Early the next morning, with forged passports representing Eugénie as an invalid English lady, Evans as her brother, a friend of Evans’s, a Doctor Crane, as her physician and Madame Lebreton as her nurse, the four left Paris in Evans’s carriage, which they soon abandoned, first in favor of a hired cab and then of the train, arriving at midnight at their destination, the French city of Deauville, on the English Channel. There they met an English friend of the Emperor’s, Sir John Burgoyne, boarded his private yacht, Gazelle, and headed for sanctuary in England.

Within six months the badly beaten French soldiers returned, their ranks devastated, much of central Paris reduced to ashes, food so scarce that many Parisians were reduced to a diet of rats. France, despite the King of Prussia’s tears, was left struggling to survive under one of the harshest peace settlements ever imposed by one European state upon another. France had to pay an indemnity to Germany of ten billion francs in a period of three years. Alsace and a large part of Lorraine were ceded to Germany, which on January 18, 1871, in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, had been proclaimed an empire under William I. Prussian militarism had triumphed.

On September 9, 1870, Victor Hugo, now a vigorous septuagenarian, had issued an eloquent appeal to the Prussians: “It is in Paris that the beating of Europe’s heart is felt. Paris is the city of cities. Paris is the city of men. There has been an Athens, there has been a Rome, and there is a Paris . . . so the nineteenth century is to witness this frightful phenomenon? A nation fallen from polity to barbarism, abolishing the city of nations; Germans extinguishing Paris. . . . Can you give this spectacle to the world? Can you Germans become Vandals again; personifying barbarism, decapitating civilization? . . . Paris, pushed to extremities; Paris supported by all France aroused, can conquer and will conquer; and you will have tried in vain this course of action which already revolts the world.”

No reply was forthcoming, and France turned to Britain and America for help. Both countries sent ships loaded with food. Much of it was held up at Le Havre because there weren’t enough men to unload the provisions. On February 26, 1870, the day the Peace Treaty was signed, 300,000 Parisians gathered in the Place de la Bastille. The temper of the crowd was ugly and one man, believed to be a spy, was nearly torn apart before being drowned in the Seine. The same day, insurgents of the growing ranks of Communards1 forced their way into the Sainte-Pélagie Prison and released political prisoners. Revolts in provincial cities followed, and in May, a violent assault on Paris, as the Communards fought for control, was begun.

Albert was awarded the Légion d’Honneur for his services to the French Navy. He had returned to Paris to inspect the Grimaldi properties—his home and that of Princesse Caroline—which had suffered severe damage during the siege. He found a city in the grip of civil war and the new president, the ultra-right-wing Adolphe Thiers, and the National Guard overwhelmed. Thiers fled with the Guard to Versailles.

Albert remained in Paris, where a second siege of the city, led by Thiers and the National Guard, followed. Despite the desperate defense of the Communards, who constructed barricades, shot hostages (including the Archbishop of Paris), and burned the Tuileries, the Hôtel de Ville and the Palais de Justice, the siege succeeded. Severe reprisals followed, with more than 17,000 people executed, including women and children. It was impossible to know just how many people had been killed in the siege. Such bloodshed had not been equaled even in the Revolution of 1792. The stench of dead flesh was everywhere.

A year later, tens of thousands of Parisians having died, the Third Republic was proclaimed with Marie Edmé Patrice de MacMahon (who had aided Thiers in the bloody suppression) as President. A monarchist of Irish descent, he had been chosen by the National Assembly to suppress the Communards and reestablish the monarchy, but he was unwilling to go to the illegal extremes necessary to do so.

Much of Paris had been reduced to rubble, food remained short, and most of Albert’s old friends were either dead or in exile. Strongly opposed to what was happening in France, he was at a loss, not knowing what he should do and suffering from a malady shared by all heirs to a throne—monarchical unemployment. He had no real job until his father died. He had already produced his own heir, and he was not a man—like England’s Edward, Prince of Wales—who enjoyed the pursuit of women.

His wife and child remained apart from him in Baden-Baden. When he returned to Monaco in the spring of 1871, the ambience in the Palace had gone from merely gloomy to positively grim. His father suffered painful gout along with his other infirmities; his aunt Florestine was a despotic shrew; and his grandmother, that strong-willed woman he had always admired, was now eighty, and terribly frail.

To add to his distress, François Blanc’s power in Monaco had increased with the infirmity of Charles and Caroline and the absence of Albert. Blanc’s only interest was in the increasing success of the Casino and his many other investments in Monaco. But he controlled the comfortable income on which the Grimaldis lived, for if the Casino should fail or Blanc should withdraw from the running of it, they would suffer a great financial loss. Albert found the man offensive, despite the continued success of the S.B.M. to his own enrichment. Blanc was arrogant and dismissive toward the Grimaldis and had even insisted the Carabinieri salute his wife when she appeared on the street. The army was unwilling to oblige until Blanc, who, it must be admitted, paid their wages, threatened to replace them. Marie Blanc, whom Princesse Caroline thought of disdainfully as being the daughter of a common cobbler, soon received smart salutes whenever she went for a stroll.

Blanc also had strong control over Albert’s father, and in 1869 had induced Charles to abolish all taxes levied on native Monégasques. With the constantly flowing income from the S.B.M. (the Casino alone made a two million-franc profit in 1872), tax money was not actually needed. But its abolition was a master stroke, for it made the Grimaldis popular at the same time that it raised Blanc to the position of benefactor of the people.

Albert was not a gambler, nor did he like the people whom Blanc and the Casino drew to Monaco. His happiest days had been spent at sea. In the spring of 1873, he left Paris for Toulon, where he bought a two hundred-ton boat, named L’Hirondelle. With a crew of fifteen seamen, he sailed in African waters for several months. When he returned, this time to Monaco, he was as much confused as to what he wished to do as he had been before. Perhaps he could have rejoined the French Navy, but it was in chaos and nearly bankrupt. He turned once again to Spain, which was engaged in a civil war, serving as a captain in the Spanish Navy for the next two years, resigning in 1875 when Alfonso XII, the son of Isabella (having been proclaimed King the previous year), entered Madrid to tumultuous cheering and restored the throne of Spain to the Bourbons. Albert returned to Monaco, where he now turned his attention to his estranged wife.

Five years had elapsed since he had even corresponded with Mary Victoria, although Princesse Caroline had kept in constant touch with her and passed on whatever news there was of his son to him. During that time, Mary Victoria had fallen passionately in love with Count Tassilo Festetics de Tolna, a dashing Hungarian, and had refused to see Albert, writing instead to ask him to apply to the Vatican for an annulment of their marriage. Rocked by this, Albert nonetheless enlisted his father’s help in carrying out her wishes. Considering that there had been a child of their union, dissolution would not be easy, if indeed it was possible. There was also young Louis’s position as heir presumptive, plus the problem of the boy’s education. Albert insisted he must be educated in France and that his school holidays be spent in Monaco. Then there was the matter of a settlement. Albert was firm that he must retain the wedding dowry, and Mary Victoria insisted upon keeping the jewels and gifts she had received. The whole unpleasant business would take four years to resolve and would cost the Grimaldis a large share of the dowry. It created such hard feelings between the Hamiltons and the Grimaldis that they never again spoke to each other.

Albert’s maiden voyage on L’Hirondelle had convinced him that his real vocation was in oceanographic studies. He sought out Professor Henri Milne-Edwards, one of the leading experts in the relatively new science and the author of one of the books (on crustaceans, mollusks and corals) Albert had taken on his honeymoon. Milne-Edwards was director of the Museum of Natural History in Paris, and Albert studied diligently under his tutelage for several years.

Victor Hugo’s “city of cities” was undergoing massive rebuilding. The bitterness of the Franco-Prussian War and the bloody siege of Paris would endure for many years. The Emperor had died in 1873 while in exile in England, where he had gone to join Eugénie. With no Court on which to center its attention, the haut monde of Paris had turned to the great salons that lionized the literary, artistic and philosophical intelligentsia.

Albert became a frequent visitor to the home of the young, vivacious, provocative and exceptionally clever Duchesse de Richelieu—none other than Alice Heine, grown and married at seventeen into one of France’s most distinguished families. The châtelaine of the magnificent Château de Haut-Buisson, and the leader of a young group of aristocratic intellectuals, she held brilliant salons in the de Richelieus’ grand and elegant home in Paris.

Princesse Caroline, who had been almost entirely bedridden since Albert’s return from Spain, died in her sleep on November 23, 1879, at the age of eighty-six. Despite the infirmities of her last years, her mind had remained sharp and she had not lost her zest for expressing her opinion. She had been a strong influence in Albert’s life, and a constant force in the lives of both her son and grandson, as she had with Albert’s father. With his grandmother’s death, and to his father’s bitterness, Albert spent most of his time in Paris.

On July 28, 1880, the Vatican finally annulled his marriage to Mary Victoria, yet declaring Louis legitimate. The previous month, Mary Victoria had married the Hungarian count in a civil service (although forbidden by Church law to do so) for she was pregnant with his child. With the Duchesse de Richelieu’s encouragement, Albert pursued his oceanographic work. Recognizing that the science lacked the necessary instruments and equipment to probe the depths of the sea, he invested a large sum of his money into their development and construction. His plan was to take L’Hirondelle on a research voyage, which would be a pioneer excursion of its kind.

Partly because of the terrible state France was in after the war with Prussia, those who could afford it made their way south to the Riviera for escape. More than 140,000 people had visited Monte Carlo in 1871. François Blanc enlarged the Casino and invested in the racetrack in Nice, wisely believing that elegant devotees of prize horseflesh would eventually come to Monte Carlo since Nice had nothing to compare with the accommodations and food of the Hôtel de Paris or the many other, newer hotels.

By now, Monte Carlo was a thriving resort city that had no equal on the Riviera. There were nineteen new hotels, twenty-four grand villas, and eighty furnished apartments. The opportunity that one might, after ten years, acquire Monégasque citizenship and so live tax-exempt brought many new residents.

But Monte Carlo had been built to please a particular social group—the international nobility and the American millionaires who were fast marrying into their ranks and adopting their standards. “The Russians might be a little more barbaric, the English slightly more puritanical and philistine, but taken all in all there was a generally accepted code of taste, of manners and maybe even of morals,” one commentator of the times wrote. “They [the social set of Monte Carlo] presented a solid, polished front to the world, as closely-knit as chain-mail; and perhaps greater even than that which their ancestors had found in moated bastions and armour plate. The newly-rich bourgeoisie modelled their behaviour as best they could on that of the people who were generally regarded [if erroneously] as their betters.”

Blanc was well aware of the social aspirations of the nouveaux riches, being one of their number himself. He decided to bring culture, which that segment of society regarded as essential, to Monte Carlo. From the beginning of the enterprise, his policy had been to provide attractions for those visitors not drawn toward the tables—wives, husbands, children and mistresses who were brought along as appendages and whose restlessness and dissatisfaction could keep the players away from the gambling.

He therefore contracted with (Jean Louis) Charles Gamier, the architect and designer of the newly completed Paris Opéra, to build a smaller version, to adjoin the Casino. It was called the Salle Garnier. Splendid caryatids decorated the corners of the interior, holding up a painted ceiling and backed by “florid frescoes along the walls, gilt cherubs on the pillars, and gilded statues of Nubian slaves brandishing massive candelabra.” The theater opened on January 25, 1879, with the appearance of Sarah Bernhardt who read a prologue written by the French playwright, Jean Aicard. The Divine Sarah was a compulsive gambler and had lost a large sum of money earlier that evening at the gaming tables, to which she returned after her performance, unfortunately to add to her losses. The Salle Garnier was to be François Blanc’s last contribution to Monte Carlo, for he died the year it was completed. His son Camille Blanc inherited his control in the S.B.M. and a fortune of over seventy-two million francs.

Despite the Salle Garnier’s new cultural contribution to life in Monaco, public opinion was strongly against Monte Carlo’s main attraction—the Casino. A Committee Against Monte Carlo for the Suppression of the Gaming Tables had been organized in 1878; the petition presented in the Chamber that year was initiated by leading inhabitants of its French neighbors—Menton, Nice and Cannes—who were fearful of losing large sums in tourist money from travelers lured to Monte Carlo by the gaming tables. When the petition was denied and the Casino continued to flourish, these towns forgot their scruples and built casinos of their own. By this time Monte Carlo had acquired a reputation as the fashionable place to gamble, one reason being that Edward, Prince of Wales, using an assumed name but with a current ladyfriend, frequented during the season.

A damning book, Monte Carlo and Public Opinion, with contributions from European and American writers (mostly anonymous) was published in England in 1884. Its appearance followed a series of reported suicides of heavy losers at the tables and stories of ruined families and runaway husbands. “Last of its kind to be tolerated in the neighbourhood of the respectable communities of Europe, the public gambling institution of Monte Carlo, in the petty principality of Monaco, has been arraigned and found guilty at the bar of public opinion, and only now awaits the sentence and final extinction which it falls to the part of the Government of the French Republic to pronounce and inflict,” the editor (credited only as “a visitor to Monte Carlo”) stated in his preface. All of the book’s contributors supported the closing of the Casino. (There were no essays in favor of the continuance of the gaming tables.)

The authors of this book all seemed to believe that it was up to France to prohibit gambling in the Principality “as there has always been a dependency on the court of France, which became, in the reign of Louis XIV, scarcely distinguishable from complete subjection. It has been renewed and reinforced, since the final withdrawal of the Italian garrison, by the transfer of its customs and civil rights to the French Government (convicted criminals are even incarcerated in French gaols). The present ruling family is in the male line descended from a French nobleman. . . . The claim of the Prince de Monaco’s friends that he should be allowed to rank as an independent prince, with a right to pass his own laws, is one that is opposed to the facts . . . the natural position of Monaco is as an enclave of France.”

An Italian by the name of Mancini wrote that “the gambling house, officially protected and surrounded by unbridled luxury, continues to add to the number of its victims, and to desolate countless families all over Europe; [the ruinous losses of Italy’s Prince Orsini which had bankrupted him had been a scandal in that country]. Every day fresh suicides appall the inhabitants of [the Riviera]. The well-paid defenders of gaming say these are mere accidents. According to them every man who flings himself over a precipice, or is dashed to pieces on the rocks, or who blew his brains out with a revolver, did so quite accidentally. . . . It is hoped that the European Powers will come to an understanding to take diplomatic action on this subject.”

A French detractor points out that “the only plausible objection against French interference is that France wishes to respect the independence of Monaco . . . but we maintain that Monaco is not an independent state, seeing that the management of affairs of importance in that state is in the hands of France.” One good reason for France’s lack of interference was the assistance of two million francs yearly that Monaco had been giving France since the war to help pay off its enormous war debt. This decision had been made by François Blanc and forced upon Charles at the time of the peace treaty with the reasoning that the newly created Germany with its powerful military force would not interfere with the gaming tables in Monte Carlo, although casinos in Germany had been outlawed, if they received sufficient compensation and it could not be traced as coming directly from Monaco and the Casino. France had also welcomed this plan, for it helped them to pay off their obligation.

Although there was a large and growing cartel in Europe and America attempting to put an end to the Casino, it continued to flourish and to fascinate and to draw to it an ever larger clientele. One American visitor gave a good description of the Casino and its ambience in 1884:

The gaming-house stands in the midst of well-kept gardens, and there are statues and seats, palm trees and terraces everywhere. . . . We mount the steps on the north side, away from the sea, and pass through the large glass doors that are held open by an obsequious official in uniform. We find ourselves in a spacious vestibule adorned with evergreen plants; a fine reading-room on the right, where papers of every country may be found; a grand ball-room and theatre in front, and a balcony all around. Most of the visitors disappear through large doors on the left. Two guards are stationed there, who say, as we advance, “No one is admitted to the gaming-rooms without tickets.” We apply at the bureau close by.

“What is your nationality?” the ticket-seller asks in French.

“We’re American,” I reply in English. Then he inscribes our names and callings in a big book and gives us tickets, which we endorse. And now, provided with tickets, the guards give way, and pushing open two pairs of swing doors, we find ourselves in the “gambling-hell” of Monte Carlo.

It is a vast hall in three divisions, with a roof supported by massive pillars. The decoration is rich—gold and brilliant colors and endless mirrors intermingled in a style which may not unreasonably be compared with some of the rooms I visited at Versailles and Hampton Court. There is a murmur of many voices, the chink of gold and silver, and a click-click like the sound of billiard-balls repeatedly tapped together with the hand. The hall contains seven gaming-tables, covered with the traditional “green cloth.” . . . At each end of the table there are . . . croupiers, who have rakes; another and superior official sits upon a high chair and surveys the table and the gamblers sitting and standing around. The roulette is motionless now, and the banker in charge of it calls out, “Messieurs, faites vos jeux!” [Gentlemen, stake your bets!]

All around the saloon are luxurious seats and gorgeously attired lackeys in attendance. But no one sits quietly there; the people are all hot and excited, both losers and winners . . . as I come out into the peaceful gardens, and look upon the Mediterranean, bathed in sunlight, I am watched by stealthy gendarmes, ready to seize me if I should attempt to blow out my brains, as the Russian gambler did the other day. Such affairs are, unfortuantely, only too common with gamblers in Monaco.

None of the controversy over Monte Carlo appeared to have any effect upon Charles III. By 1880, now sixty-two, he was seldom seen, even by former friends who had once presented themselves at the Palace when they were in the Principality. Albert was off on his long-awaited maiden research voyage. (He was to go on twenty-six such journeys and would establish for himself a position as one of the foremost authorities on oceanography.) Charles worried a great deal about Albert and his wanderlust, not understanding what his son could find so fascinating in dredging up fossils and sea life from the bottom of the ocean. He dictated letters asking him to return home, as he was old, ill and lonely. He was also richer than he had ever dreamed. He left the running of the S.B.M. to Camille Blanc while he concerned himself mainly with decisions regarding the Palace and its staff.

Despite their annulment agreement, Albert and Mary Victoria’s son, Louis, spent his holidays from 1877 until 1880, when he was ten years old, with his mother in Baden-Baden (before that time he had lived there in her care). This was mainly due to his father’s occupation with the French and Spanish navies and his scientific ocean travels. Until this time Albert did not appear to bear his ex-wife ill will. His feelings toward her changed at Eastertime when they had an exchange of angry letters apparently precipitated by Mary Victoria’s removal of Louis, without Albert’s permission, from the school he was attending in Paris, because she thought it was too cold and disciplined. In the summer of 1880, Louis visited his father for the first time in Monaco before beginning studies at his father’s former boarding school, the Collège Stanislas. “He was pleased to see you, Sir,” Mary Victoria wrote to Albert, her tone now conciliatory. “[He] never makes any reference to the past. He takes everything so naturally, and we should thank God for it, and try to keep this delightful frankness intact as long as possible.”

Louis entered the Collège Louis-le-Grand in 1883. But Albert, although by then more attentive, saw little of his son in the next few years, even when he was in Paris where the school was located. He made more research voyages on L’Hirondelle, during one of which the ship was caught in a cyclone and nearly overturned. He studied the drift of surface currents in the North Atlantic, the Gulf Stream in particular, using specially designed floats he had commissioned; and he dredged the seabed at a depth of nearly ten thousand feet, an operation that took three and a half hours to lower the special equipment, and triple that time to raise it again. He returned from each of his voyages to Paris where he continued studying with eminent oceanographic scholars. He had become obsessed with the subject but it was not the only attraction in Paris.

The Duc de Richelieu, a comparatively young man, had died suddenly and Alice was now a widow—a very rich widow—having been left seventeen million francs. Whenever Albert was in Paris, he spent what time he could with her, attending her lively salons in her exquisite home in the Faubourg Saint-Honoré.

12

ALICE WAS UNLIKE any other woman Albert had ever known. There could hardly have been two more contrasting personalities than Mary Victoria and the Duchesse de Richelieu. Possessing a brilliant mind and a dazzling knowledge of a variety of subjects from literature to politics to science, Alice conducted a salon that greatly appealed to France’s intellectuals. As a young man of seventeen, Marcel Proust was a guest there (she was fourteen years his senior) and became one of her great admirers. Years later, he used her as model for the Princesse de Luxembourg in À la recherche du temps perdu.

Proust described the Princesse de Luxembourg as “tall, red-haired, handsome, with a rather prominent nose. . . . [I saw her] half leaning upon a parasol in such a way as to impart to her tall and wonderful form that slight inclination, to make it trace that arabesque, so dear to the women who . . . knew how, with drooping shoulders, arched backs, concave hips and taut legs to make their bodies float as softly as a silken scarf about the rigid armature of an invisible shaft which might be supposed to have transfixed it.” He thought Alice very beautiful and her voice “so musical that it was as if, among the dim branches of the trees, a nightingale had begun to sing.” And he referred to her as “a woman of the soundest judgment and the warmest heart.” He was, perhaps, somewhat in love with her, but then so were many of the men of all ages who came to her salon.

A combination of her exotic mother and her pragmatic father, even in appearance, Alice spoke many languages—all fluently and all with a melodic American Southern accent, although she had left her native New Orleans when still a small child and had returned only twice to visit her grandparents. She introduced Creole cooking to the Parisian elite and seemed more inclined in style to Spanish than to German influences. She drove in a stately equipage, always followed by a small black page dressed in red satin.

She was close to her family, but fiercely independent. Her brother, George, had gone into the Heine banking business; and her mother, who enjoyed being the grande dame, spent most of her time entertaining lavishly at her daughter’s country estate, the magnificent Château de Haut-Buisson (where she now lived), for Alice preferred to be in Paris. Since childhood, Alice’s daughter, Odile, and her son, Armand, had been admitted to their mother’s sophisticated salon. Gay, witty, wise, iconoclastic, cultured, wealthy and a striking beauty, Alice attracted her share of fortune hunters and a succession of lovers.

She was initially drawn to Albert because of his adventurous spirit. Always ready to learn about subjects previously unknown to her, she found his knowledge of oceanography and his voyages off the coast of Africa interesting. He also had a certain masculine mystique about him, unlike the intellectual, artistic and sometimes effete men who were part of her set. Albert liked the sea, hunting and adventure, yet he was extremely intelligent. He was the heir to a throne, but he was a simple man, of simple tastes. Conscious of her height since childhood (she was about five-feet seven, tall for a woman of that time), she found that his bearlike build made her feel smaller.

When he declared his love for her in 1885, she was twenty-eight and he was thirty-seven. He wanted above all else to make her his wife, but to do so he had to have his father’s permission. Charles withheld it. This was not, presumably, on religious grounds, for Alice had converted from Judaism to Catholicism when she became the Duchesse de Richelieu. She was a widow and they were both free to marry. But the old monarch considered it scandalous that a single woman would conduct a salon and was a friend to writers and artists for whom he had no tolerance. In addition, her Jewish heritage provoked a degree of snobbery in him. Despite his disapproval, Albert and Alice became lovers. On his return from his scientific explorations he would go straight to her house in Paris. At least twice they rendezvoused in Funchal, the capital of Madeira.

Charles III died at seventy-one years of age, after falling ill with pneumonia while on a visit to Marchais, on September 10, 1889, his daughter, Florestine, at his bedside. Although the Palace flag was lowered to half-mast and photographs of him that were on display in public buildings draped in black, his death was unmourned by his subjects. A total recluse for the last decade of his life, when in Monaco he never left the Palace. The end of his reign had cast a pall over the Principality. It had been years since there had been a royal ball or official visits from other royals or heads of state. Festive occasions were centered in Monte Carlo, which now had become a prospering city. Charles III would be remembered as the Prince for whom the city had been named and his reign as the start and rise of the gambling Casino there. But of the Grimaldis, it had been his mother, Princesse Caroline, in conjunction with François Blanc, who had made the greatest impact on his subjects, their lives and economic well-being.

Charles and Albert had never been close and shared little in common. Their relationship had grown more difficult after Princesse Caroline’s death, for Albert was seldom in Monaco and managed to visit Marchais at times when Charles was not there. During the infrequent times they were together Charles was critical of his son’s scientific endeavors (which he considered a waste of effort and money) and his associations. His dictated letters to Albert reflect his dissatisfaction with almost everything his son did. He expected Albert to spend more time with him, to have greater sympathy for his blindness and ill health, and to take over more duties in Monaco. Instead, Albert involved himself more with his scientific expeditions, and when he was not at sea, he was with Alice in Paris.

He was at sea when he was informed of his father’s death and altered his course back to Monaco. On October 23 he accepted the oath of loyalty in the courtyard of the Palace. The ceremony had not been performed there since 1731, when the young Honoré III had returned to succeed his mother, Louise-Hippolyte. For the first time in years there was great celebration in Monaco, but almost immediately after he became Albert I, Prince de Monaco, he departed for Paris; and on October 31, accountable now only to himself, he married Alice in a quiet service in Paris with only her family and a few close friends present. They honeymooned in Madeira, then returned to Paris, where they were the guests of honor at several large balls. On February 9, 1890, the newlyweds (the bride with twenty-seven trunks filled with her new fashionable trousseau) arrived by train in Monaco and were met by an enthusiastic crowd.

Twenty years had elapsed since Albert had brought his first bride to Monaco. In the interval, the Principality had become the cosmopolitan hub of the Riviera, a gathering place for royalty, society, heiresses, fortune hunters and gamblers out to break the bank at Monte Carlo (now called just “Monte” by the cognoscenti). What it was not, despite the Salle Gamier, was an intellectual and cultural citadel.

Once Alice was installed as châtelaine of the Palais de Princier, many members of her intellectual and artistic coterie began to visit. Monaco enjoyed a new recognition with the Princesse de Monaco’s smart soirées. Alice had to contend with Albert’s Aunt Florestine (more testy than ever with her position suddenly usurped), but she did so with amazing finesse. Alice saw to it that Florestine was given a larger suite of rooms, which incorporated Princesse Caroline’s former apartments, and that she was drawn into the extravagant and exciting redecoration being undertaken. The former gloom of the Palace was dispelled by new and brighter upholstery and curtains. Bowls overflowing with brilliant flowers graced the rooms, and the gardens became an attraction few visitors could resist.

The parade of royal guests to the Palace began. The season officially started the week before Easter with the arrival of the Prince of Wales on his yacht Britannia. He much admired Alice and often came to the Palace for tea. His long alliance with the beautiful actress Lillie Langtry was over (although she retained a villa in Monte Carlo and they remained friends), and he was now usually in the company of the worldly and charming Mrs. Keppel, the spirited and attractive wife of a Gordon Highlander. Alice Keppel appeared to have cured his roving eye and would become his constant companion for the remainder of his life.

He arrived in Monaco accompanied by a small personal staff, his physician, two equerries, two menservants and a butler. Although he insisted on being called Baron Renfrew, his small canine pet, who followed him everywhere, wore a jeweled collar with the inscription: I am Caesar. I belong to the Prince of Wales. He went to the Casino almost every night to play baccarat but did not wager large sums that would attract comment.

The Grand Duke Michael, uncle of Czar Alexander III, led the procession of Russian nobility to Monte Carlo. The Russians lived on a far grander scale than the Prince of Wales, who was related to many of them. Russia’s Empress Maria Fëdorovna was his wife’s sister, and his cousin Princess Alix of Hesse was married to another cousin, the Czarevitch Nicholas. The Russians spent fortunes, losing millions of francs in a single night at the Casino, rented whole floors at the Hôtel de Paris and the other hotels, and hired innumerable servants, dressing them in powdered wigs and livery.

King Leopold II of Belgium, whose private life was even more scandalous and dissolute than that of the Russians, also came to Monte Carlo every season, first making his way up the curving road of the Rock to pay his respects to the new Princesse de Monaco. And there were Arabian princes and the Prince of Nepal, whose religion allowed him to gamble only five days a year.

Albert’s scientific sea ventures increased and he was away from Alice for longer and longer periods. Municipal decisions such as zoning and building restrictions and budgetary problems were handled by the S.B.M., with the enriching assistance of Michel Heine in financial matters.

The new Princesse de Monaco enjoyed the prestige of the noble visitors who were attracted to Monaco; but she was disdainful of their reasons for coming, and she was only too aware of the courtesans and expensive whores who flocked to Monte Carlo during the season to the delight of Monte’s many jewelry concerns and fashion houses. What Alice wished was to make Monte Carlo an important cultural center, attractive to the artists and intellectuals who had been part of her salon in Paris. To accomplish this she would need to change the image of the town by constructing and developing diversions other than gambling—the arts, sports and horticulture, starting exotic gardens that would be open to the public. She wanted more charity galas to counteract the Casino’s bad publicity and growing numbers of con men and desperate characters attracted by the free flow of money at the gaming tables. Also, Albert was never easy about the idea that his wealth was based on gambling losses.

“When I first knew this Princelet, he was always talking of his dislike of ‘the gambling house’ of Monte Carlo, which gave him his princely revenue and paid besides all the expenses of his three miles long and half a mile wide kingdom,” author Frank Harris, who lived on the Riviera and was a close friend of Princesse Alice’s, wrote in his autobiography, My Life and Loves. “Everyone staying at the palace was requested not to visit or even enter the gambling house, and the Prince was continually complaining that his father had given M. Blanc a lease of the place till [1913], or else, ‘I’d shut it up tomorrow. I hate the corruptions of it . . . I loathe the place.’

“It seemed to me,” Harris continues, “that the Prince protested too much; in any case, surely he need not have accepted ‘the wages of sin,’ had he not been so inclined.”

Albert had, in fact, given his father-in-law, Michel Heine, the go-ahead to try to renegotiate François Blanc’s original contract on better terms, even if it meant extending the lease, for he needed a great deal of money to construct an oceanographic museum in Monaco, to be the first of its kind and the largest and most complete in the world.

Michel Heine brought Camille Blanc to the negotiating table with threats that Alice might use her influence to close the Casino if changes were not made. Although François Blanc’s original agreement had another twenty-three years to run, Heine secured a new contract with an immediate payment of 10 million francs to the state treasury and a payment of 15 million francs to be made in 1913, the year the Blancs’ concession expired. A further 5 million francs was to be paid by Blanc for harbor improvements, with an equal amount to go to local charities, 2 million francs for the construction of an opera house to adjoin the Casino, and 24,000 francs for each of twenty-four operatic performances a season. The Prince de Monaco would also receive an additional 1,000 shares of stock in the S.B.M., increasing his holdings to 1,400 shares, and 125 million francs plus 3 percent of the first 25 million francs staked on the gaming tables.

Plays and operas had been presented in a concert room at the Casino before the Salle Garnier had been completed, generally by traveling companies whose main function was to provide light entertainment, with short acts and long intervals to allow time for bets to be placed on the gaming tables. Comedy and vaudeville had been the mainstays of these programs. Alice set to work, with Albert’s approval, to bring complete operas with the world’s leading performers to the new Monte Carlo Opera House. With a generous contract and the title of Director of the Monte Carlo Opera, she secured the services of thirty-two-year-old Raoul Gunsbourg, an impresario who had been a member of her Paris salon (and possibly a former lover).

Born in Bucharest, the grandson of a rabbi and the son of an army administrator, Gunsbourg had spent much of his childhood in China, where his father was sent on a tour of duty. A remarkably gifted pianist, he had nonetheless wanted to become a doctor and obtained a baccalaureate at the age of fifteen. His studies in Bucharest were interrupted by the Russo-Turkish War, in which he served with the Russian Army as the chef de musique militaire. After the war he went to Paris to continue his medical studies, but suddenly decided he wanted to work in opera or the theater. To support himself he took a job as the theater critic and then editor of a weekly publication. He met Alice in the early 1880s and she encouraged him to try his hand as a concert manager and then as an impresario. She helped him finance the staging of a theater version of Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days and operas by Saint-Saëns, Offenbach, Mozart, Meyerbeer, Verdi and Massenet in France and Russia.

Gunsbourg was a bullish, dynamic man with an explosive temper and a hearty laugh. From the moment he stepped off the train in Monte Carlo, he swung into immediate action. During its first season, 1892–1893, the new Monte Carlo Opera presented nine operas (with Nellie Melba as leading diva), six comedies (two starring Bernhardt) and four operettas. With the success of this premier season, Alice grew more ambitious and asked Gunsbourg to include works by new composers the following year.

Enter Isidoro de Lara, formerly Isidore Cohen. Born in London in 1859, he had been a piano prodigy before he turned to voice and, finally, composition, studying at the Milan Conservatory. When he returned to London, he wrote songs and became one of the favorites of the London social set. He sang his own works in a pleasant baritone, accompanying himself on the piano in the city’s finest houses.

His first opera, The Light of Asia was performed in March 1893 at Covent Garden to encouraging reviews. Gunsbourg had received a manuscript of the score of de Lara’s new opera, Amy Robsart, scheduled for spring 1894 at Covent Garden, and contracted to present it the following December. De Lara came down to Monte Carlo to discuss the production. Alice was not greatly taken by him when they first met, although she thought his music displayed an unusual talent. He had a curious appearance. Under five feet tall, he had a hunched back and arms and shoulders that were overdeveloped for his size. But he had a stunningly handsome face, huge burning dark eyes, a strong Roman nose, and robust, swarthy coloring. His success had given him an aura of great self-assurance, and he exuded a seductive charm.

The opera was only moderately well received in Monte Carlo, but Alice was drawn to the strange and romantic de Lara, and insisted that Gunsbourg sign him to a six-year contract that called for two new operas and allowed him to direct two other works of his choice each season. De Lara quickly became an integral part of Monte Carlo’s cultural life, and he and Alice saw each other with growing frequency, meeting—when Albert was on a scientific expedition—as secretly as was possible for the Princesse de Monaco to manage in her own small Principality.

Raoul Gunsbourg appears to have been more distressed by the growing intensity of the relationship between Alice and de Lara than Albert was. Gunsbourg simply did not appreciate being commanded to engage a particular artist. On December 20, 1895, with de Lara’s The Light of Asia scheduled for the following spring, he had two new stipulations added to his own contract, giving him complete authority in the hiring of all personnel and the absolute right to choose his artists and the works to be presented without the approval of either the Prince or the Princesse de Monaco. This still left him with the preexisting contract with de Lara.

With the Monte Carlo Opera and Alice’s glittering sequence of seasonal charity galas, the town spun dizzily into its golden age. Rich American heiresses and needy titled foreigners increasingly used it as a mating ground. To an unwed heiress, a title was worth anywhere from $200,000 to $4 million. American sewing-machine millionaire Isaac Singer paid $2 million for each title for his daughter Winnaretta. She first became a duchess and then, when divorced and remarried a year later, the Princesse de Polignac; and her sister, Isobel, became the Duchesse de Decazes.

This barter in titles seemed no more moral than that of the great courtesans who demanded jewels, clothes and carriages for their favors, and perhaps it had even less to do with the honest emotions of love and sexual attraction. The American ladies, who were the buyers in this case, were quick to adapt to their newly purchased aristocratic station. Tea at the Hôtel de Paris was de rigueur. (A few years earlier a British guidebook had written that the hotel “cannot be recommended as a family hotel, since so many gamblers stay here. If the rooms must be visited, the ladies of the party should be left outside.”) Literary, opera, and poetry societies, sports and garden clubs and numerous charity organizations were formed and were the foundation of the season’s social and cultural activities.

Alice had hoped her friendship with the Prince of Wales might influence his mother to visit Monaco during her usual springtime stay on the Riviera. Queen Victoria was adamant in her refusal to do any such thing. Her son’s gambling losses and those of the Russian aristocrats in Monte Carlo were well known to her, and she would have nothing to do with the place or the Prince and Princesse de Monaco. In 1899, when she was ensconced at the Hôtel Excelsior Regina in Cimiez near Nice, her entourage related stories to her about the local Russian pawnbroker who “lends money to the miserable [Russian] wretches on their way to Monte Carlo and they are generally unable to redeem their pledges, so he acquires splendid jewels for next to nothing and can afford to sell them cheap.”

When the Prince of Wales’s discreet suggestions to his mother that she would enjoy meeting the Princesse de Monaco had no effect, Alice wrote a letter to the Queen, asking if she and Albert could call on her. Such a request could not be overlooked, and Queen Victoria had them to tea at her hotel. Her reception was decidedly cool and the tea hour exceptionally brief. Alice did, however, meet the Princess of Wales with whom she hit it off extremely well, and her daughters, “seedily dressed and Maud [future Queen of Norway] with garish dyed yellow hair.” But she was not unaware of Queen Victoria’s disapproval, or the snub of her avoidance of Monaco. Albert had bought a new and large boat to use for his scientific expeditions, which he named Princesse Alice. He was beginning to distance himself from his wife, his Principality and his son, as he became even more deeply immersed in his research voyages, oceanographic societies and a new interest, paleontology. When not at sea, he would explore the caves near Menton, called Rochers Rouques, and in his diggings, he discovered bone fragments of the Cro-Magnon period. For a number of years, while he planned the building of a museum, they were housed, along with other prehistoric remains of fossilized animals and Roman findings, in the ancient dungeons beneath the Palace.

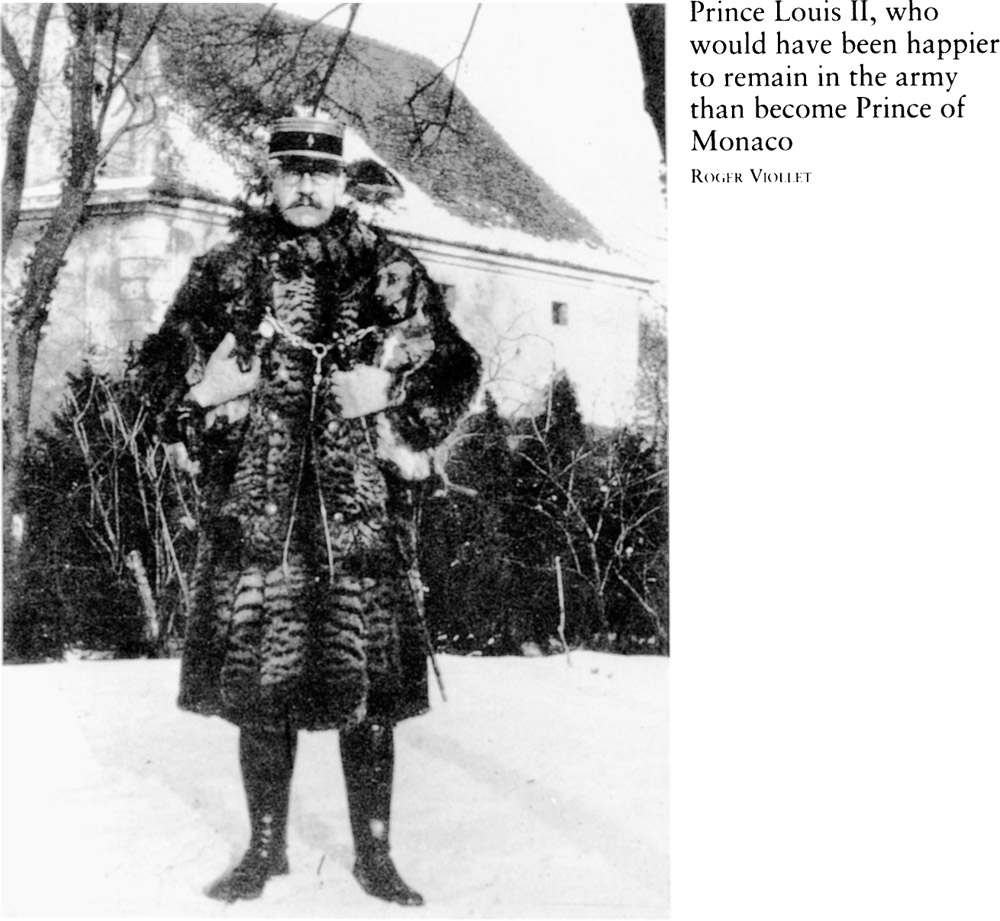

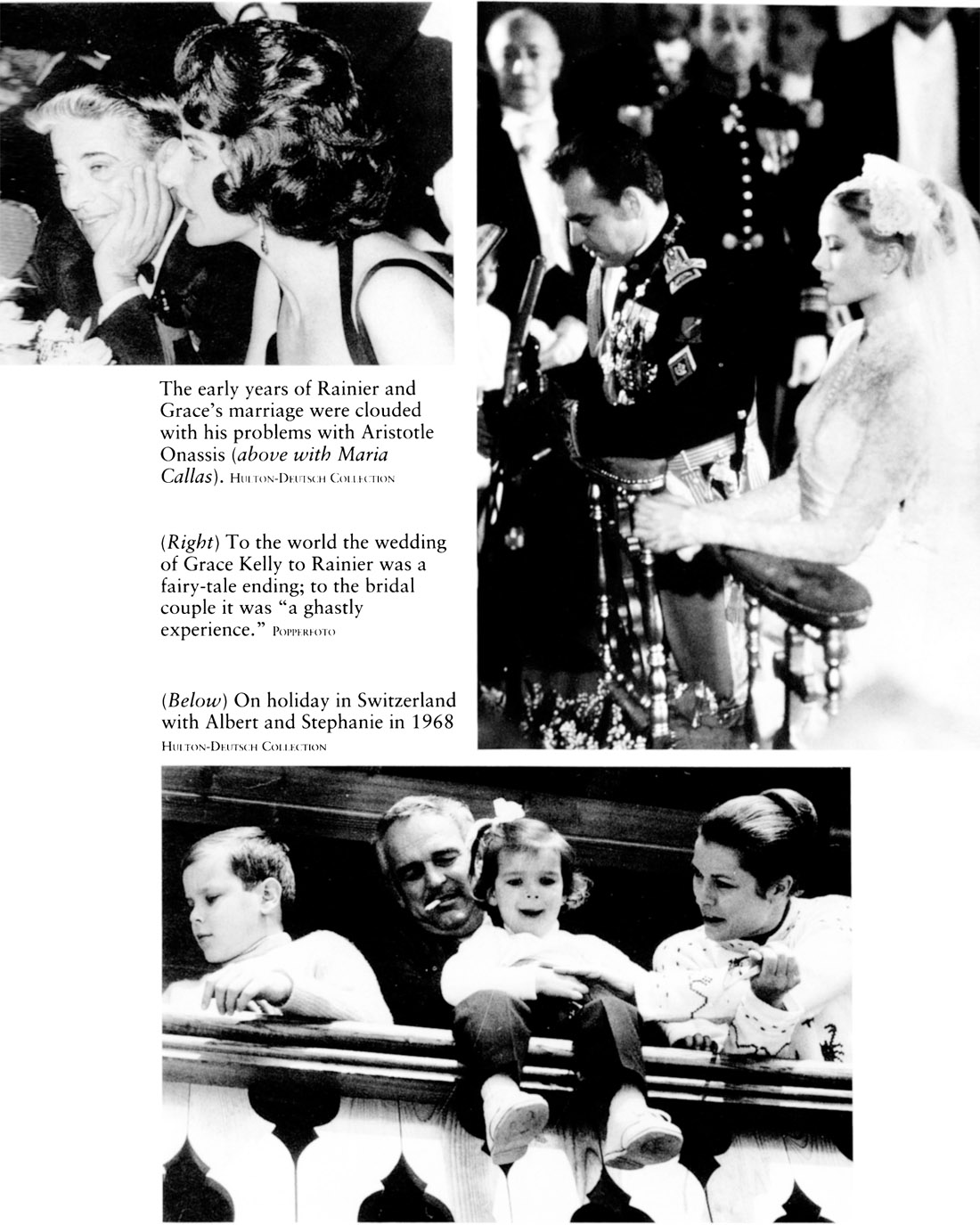

Louis had entered L’École Corneille in Paris in 1889, the year his father had ascended as Prince de Monaco. He had none of the intellectual leanings and curiosity of Albert and did poorly in most of his courses, with the exceptions of fencing and horseback riding. The idea of a military career excited him, and at Albert’s suggestion, he applied for admission to the Swedish Army, knowing he would be well received and that it might do him good to travel abroad. But on May 6, 1890, he wrote his father: