Chapter 4

The Mediterranean Banking Systems: Convergence or Path Dependence?

Massimiliano Affinito and Riccardo De Bonis1

Abstract

This chapter studies the convergence of banking indicators in the Mediterranean economies, an area including 19 European, Asian and African countries. We compare banking convergence, measured by the ratios of deposits and loans to GDP, with convergence of per capita income, using 20 European Union countries as control sample. We assembled a large dataset starting from the Sixties. The econometric exercises apply the concepts of beta, sigma convergence and stationarity tests. We also tried to detect the existence of convergence clubs, i.e. subsets of countries that are more similar than the Mediterranean nations as a whole. We obtained three main results. First, in the Mediterranean countries some convergence of banking indicators exists, mainly for deposits, but it is weaker than in the EU countries. Second, per capita income convergence did not take place in the Mediterranean area, while there is evidence of it in the EU countries. Third, splitting the Mediterranean area into smaller sets of countries, we found real convergence for the clubs of African and Arab countries, while banking convergence was confirmed for European nations.

1 Introduction and Motivation

Financial systems differ for size, types of intermediaries and instruments, intensity of innovations and corporate governance rules. However market globalization, capital mobility and deregulation programmes led some scholars to argue that those differences will eventually decrease or even disappear. Many studies have investigated whether convergence of financial systems is taking place in European countries, led by the single internal market and the common monetary policy. As a part of the growing debate on financial convergence, this chapter focuses on countries on both sides of the Mediterranean Sea. These European, Asian and African countries form an interesting panel due to their historical links, trade linkages and, at the same time, different levels of per capita income and financial system development.

Despite the absence of a common monetary policy and political framework, as in the euro area, financial convergence in the Mediterranean countries could have been triggered by their long common history and commercial relations and by the efforts of the poorer countries to replicate the success and the institutions of neighbouring richer countries, including similar legal systems, often spread through colonization.

While theoretical results are well established for the convergence of growth rates of per capita GDP,2 no economic theory of long-run convergence of financial structures has yet been developed, making the hypothesis of financial convergence more difficult to handle. In the end, the search for financial convergence is mainly an empirical issue, but an important one as the real growth of the economies may be influenced by different degrees of financial development, as shown by a large stream of literature.3

In this chapter, the hypothesis of banking convergence across Mediterranean countries is tested against the hypothesis of path dependence by looking at two indicators: the ratio of loans to GDP and the ratio of deposits to GDP. The empirical analysis takes advantage of country statistics collected by the International Monetary Fund. We assembled a large dataset starting from the Sixties, since convergence must be evaluated using long time series. The econometric exercises use several methodologies: β-convergence shows whether countries tend towards a common long-run benchmark; σ-convergence measures if countries become more similar over time; stationarity tests detect the existence of separate clusters of countries.

The chapter is divided into six sections. Section 2 briefly reviews the literature. Section 3 presents the research strategy and the methodology used in the estimations. Section 4 describes the data, and Section 5 illustrates the econometric results. Section 6 concludes.

2 A Review of the Literature on Financial Convergence

According to the Oxford Dictionary, convergence is ‘the tendency to become similar while adapting to the same environment’. Several international and supranational organizations have financial convergence as a goal. These organizations foster the harmonization of regulation to provide equal competitive conditions for economic agents. The most recent examples are the introduction of the Basel 2 agreement and international accounting standards. Financial convergence has been particularly pursued in Europe, where, since the Seventies, directives tried to ensure a level playing field for banks and other intermediaries.4 However the harmonization of rules is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition to achieve convergence of financial structures and indicators.

On the empirical ground, financial convergence has been discussed examining the various sectors and products that make up the financial system and using price and quantity indicators. In this paragraph we review the most important strands of recent research. This literature has dealt almost solely with European countries, which are expected to converge earlier than other areas in the world. Convergence has been discussed for price indicators, such as (i) market and (ii) banking interest rates, and quantity indicators, such as (iii) the balance sheets of households, firms and intermediaries and (iv) the composition of bank balance sheets.

(i) Convergence of Market Interest Rates

For interbank interest rate, euro-area convergence was achieved in January 1999, when the common monetary policy started. Convergence of rates on ten-year government bonds was very high but still less complete than for interbank rates; it was triggered by the criteria set in the Maastricht treaty and was already largely underway by the end of 1997. The convergence of interbank and ten-year government bond rates was linked to the fall in inflation and in inflation differentials since the early 1990s.5 After the converging period ended in the second half of 1999, the cross-country standard deviation of European inflation rates picked up in 2000 and remained relatively stable thereafter.6

(ii) Convergence of Banking Interest Rates

According to the law of one price, in the absence of transport costs, trade barriers and information costs and assuming perfect competition, the price of a good does not depend on its location. However, in banking markets informational asymmetries, borrower risk, market power, and home bias jointly undercut the validity of the law. Despite the common monetary policy, banking markets are still segmented. Differences in product characteristics, degree of liquidity, collateral practices, customer risk, and market power are the most plausible explanations for cross-country differences in banking interest rates.7 It remains an open issue to select a narrower set of factors able to explain satisfactorily the heterogeneity of banking interest rates.

(iii) Convergence of Financial Indicators and Structures

Convergence of financial structures is often measured using balance-sheet data for households, firms and financial intermediaries, notably banks. Using flow-of-funds statistics for seven European countries for the years 1972-96, Murinde, Agung and Mullineux (2004) found convergence of equity issues and internal firm finance, but not of bank loans and bond issues.8 Also, Di Giacinto and Esposito (2007) found β-convergence for indicators of financial development of 13 European countries, but not for banking business.9 Examining components of financial assets and liabilities in euro-area countries, Hartmann, Maddaloni and Manganelli (2003) found that the dispersion of currency, deposits and loans increased between 1995 and 2001.10 Bond investment and financing, on the contrary, became more uniform. Studying 12 European countries in the period 1995-2000, Bartiloro and De Bonis (2005) found ß-convergence but not β-convergence for the ratio of financial assets (liabilities) held by residents to GDP.11 Analysing a longer period, from 1980 to 2000, Byrne and Davis (2002) found evidence of β-convergence, towards a more market-oriented financial system, for the balance sheet structures of the UK, France, Germany and Italy.12 Schmidt, Hackethal and Tyrell (1999) found that particularly France had moved towards a more market-oriented system.13 Bianco, Gerali, Massaro (1997) presented a comparison of six developed countries’ financial systems, based on their characteristics in the mid 90s as they emerge from financial accounts. The analysis suggested that convergence across financial systems was still limited and major changes were under way in only one of the countries considered (France).14

It is difficult to draw a synthetic conclusion from this literature, because it refers to different periods and countries and uses different statistics and econometric methods. In a nutshell, we can say that convergence has been found more frequently for phenomena like equity share issues than for banking indicators. As regards bond issues, forms of convergence were detected after the birth of the euro area, when securities issued by corporations rose sharply in most of the countries. Similarly Baele et al. (2004) found a high degree of integration in the pricing of corporate bonds across the euro area.15

(iv) Convergence in the Composition of Banking Balance Sheets

Another approach looks at convergence in the composition of banks’ balance sheets, i.e. the weight of balance-sheet items in total liabilities or assets. On the one hand, the single European monetary policy might produce similar changes in balance sheets in different countries. On the other hand, European banks move from different initial balance-sheet structures, for example in terms of liquidity. Thus, a change in the monetary policy stance will, in the example just posed, trigger different variations in the supply of credit from country to country because of differences in individual banks’ liquidity.16 Moreover, balance sheets will remain different because they will continue to reflect the characteristics of the local economy, such as product specialization and importance of small firms, and to be affected by institutional specificities, such as accounting standards, private-law rules and the efficiency of the civil justice system.

Moving to the empirical ground, Dahl, Shrieves and Spivey (2006) studied product lines and financial structure for a sample of European banks in the period 1994-2002: their evidence rejected the hypothesis that banks in different European countries have common activities.17 Also, Affinito, De Bonis and Farabullini (2006) found that dispersion is high for many of the principal balance-sheet aggregates among the national banking systems of the euro area. Two econometric exercises show the persistence of country effects in the composition of national banks’ balance sheets. However, dispersion of the banking business is not as high for Germany, France and Italy, testifying to the greater homogeneity of their economies.18

3 Research Strategy and Methodology

Taking into account the different concepts and views of financial convergence, we chose to follow approach (iii), i.e. studying convergence of two typical banking indicators: the ratios of deposits and loans to GDP. We will not focus on convergence of market interest rates, the approach under (i), owing to the lack of efficient interbank and financial markets in several Mediterranean countries.19 Neither will we follow the line of research under (ii), because in Med nations banking interest rates have been liberalized with a different temporal pattern and long, harmonized statistics do not exist.

Under approach (iii) we put the emphasis on banking business because only few Mediterranean countries produce financial accounts, and stock market capitalization is often very low.20 It is also problematic to analyse the convergence in the composition of banking balance sheets (approach iv), given the absence of good statistics for all the Mediterranean countries. On the contrary, the ratios of deposits and loans to GDP are available for all the countries and are indicators usually utilized to measure the size of banking systems.

We use two methodological approaches to analyse convergence. The first approach is based on β- and σ- convergence; the second is based on unit root tests.

First Approach: β-and σ-convergence

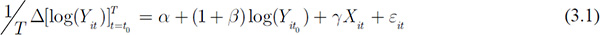

The concepts of β-and σ-convergence were developed in the empirical literature on growth.21 This literature typically regresses the average growth rate of per capita income on its initial level and interprets a negative correlation as a sign of convergence, calling it β-convergence. In other words, this literature says that there is β-convergence if poor economies tend to grow faster, and then to ‘catch up’ richer countries. We study β-convergence using the equation:

where Yit is the variable of interest for country i at date t;  is the average, between the first period t0 and the last one T, of first differences of logarithm of Yit, corresponding to its average growth rate; logy is the logarithm of the initial level of the variable of interest; εit is an error term. In (1.1) a negative β signals convergence, and the magnitude of β denotes the speed of convergence.

is the average, between the first period t0 and the last one T, of first differences of logarithm of Yit, corresponding to its average growth rate; logy is the logarithm of the initial level of the variable of interest; εit is an error term. In (1.1) a negative β signals convergence, and the magnitude of β denotes the speed of convergence.

Following the literature on economic growth, we distinguish between absolute and conditional convergence. Convergence is absolute if β is negative in a univariate regression, i.e. without controlling for additional variables on the right-hand side of the equation (3.1), then Xit = 0. Convergence is conditional if we obtain a negative β after allowing for other country structural characteristics Xit. Conditional convergence implies that, even if countries do not reach the same level of per capita income, they can reach their respective steady states. Therefore, conditional convergence suggests that a country positioned further below the steady-state level tends to grow faster. In testing cross-country convergence, it is necessary to control for the differences in steady states of different countries.22

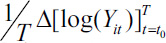

There is σ-convergence when the dispersion of real per capita income across groups of economies tends to fall over time. We obtain σ-convergence from the following equation:

where  is the mean of the logarithm of Yit.

is the mean of the logarithm of Yit.

Although related, the two indicators have different informational contents (Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 1995).23 β-convergence does not imply σ-convergence, being a necessary but not sufficient condition for σ-convergence. In other words, mean reversion is not an indication that cross-sectional variance decreases over time.

Second Approach: Tests of Zero-mean Stationarity

The second methodology is based on the strategy proposed by Harvey and Carvalho (2002) and Harvey (2002).24 According to these authors, when two series are convergent, their difference Dit is zero-mean stationary. This empirical strategy too was developed in the literature on economic growth. Bernard and Durlauf (1995 and 1996), Evans and Karras (1996) and Tsionas (2000) suggested tests which examine differences in per capita income across countries.25 They show that convergence exists if the differences between any pair of countries do not contain a unit root or a time trend.

In formal terms, let Dt be the difference between two economies, the series are convergent if:

where ci = 0 when convergence is strong, while weak convergence has ci ≠ 0 for some i. If countries do not converge, then they have their own long-run trends.

To have convergence, Dit has to be stationary, i.e. Dit has to be integrated of order zero, denoted I(0). Contemporaneously the two series composing Dit have to be integrated of order d, I(d) with d > 0, where I(d) indicates a series that becomes stationary only after being first differenced d times.

In our framework we take the ratios of deposits and loans to GDP and calculate the differences Dit between each pair of countries. Then we examine whether Dit is a zero-mean stationary process. We use an econometric exercise divided on two steps. The first step relies on the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test; the second step is based on the Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin (KPSS) test. The preliminary ADF test verifies whether the differential Dit is a nonstationary or stationary process.26 Then, the KPSS test verifies the zero-mean stationarity of differential Dit.27

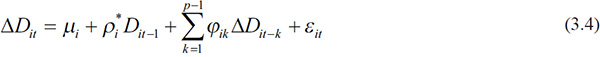

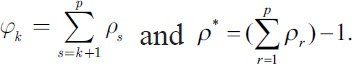

In formal terms, the ADF test verifies if a unit root is present by testing the null hypothesis ρ*i = 0 against ρi*< 0 in the following equation:

where  The test signals convergence if ρi*< 0, i.e. if it rejects the hypothesis that a unit root is present; or equivalently when ρi < 1, i.e. when it rejects the hypothesis of non-stationarity.

The test signals convergence if ρi*< 0, i.e. if it rejects the hypothesis that a unit root is present; or equivalently when ρi < 1, i.e. when it rejects the hypothesis of non-stationarity.

Once the stationarity of the series has been verified, in the second step the KPSS test verifies the zero-mean stationarity, rejecting this null hypothesis for large values of ζ statistic:

where  is a non-parametric estimator, robust to autocorrelation and to heteroscedasticity, of the long-run variance of Dit.

is a non-parametric estimator, robust to autocorrelation and to heteroscedasticity, of the long-run variance of Dit.

The ADF and KPSS tests can be applied alternatively either to the bilateral differentials  between each pair of countries or to the difference

between each pair of countries or to the difference  between each country and the cross-country average. We use both methods. Bilateral differentials are useful to gain an overview of general convergence. Differentials from the average are useful to detect the existence of separate clusters around different cross-country averages.

between each country and the cross-country average. We use both methods. Bilateral differentials are useful to gain an overview of general convergence. Differentials from the average are useful to detect the existence of separate clusters around different cross-country averages.

In the first case,28 the bilateral differentials  between each pair of countries are defined as:

between each pair of countries are defined as:

where superscript j indicates that the difference D is between countries i ≠ J.

In this case, we can state that two countries are convergent when the differential Dj between them is a zero-mean stationary process. If the two tests are repeated for all pairwise differentials among the analysed countries, the total number of bilateral differentials is: N(N – 1)/2.

In the second case, the differences of each country from cross-country average are:

where superscript A indicates that the difference Dit is between each country i and their average

The cross-country average represents the common, long-run trend. The series converge if the deviations of individual series from their average is expected to reach a constant value as t tends to infinity.

4 The Data

To analyse convergence we need long time series, a control sample of countries to better interpret results, different indicators to get robust tests, and some proxies of country structural characteristics to verify conditional convergence. The natural setting for this exercise is a panel-data framework that allows the analysis of different countries over time.

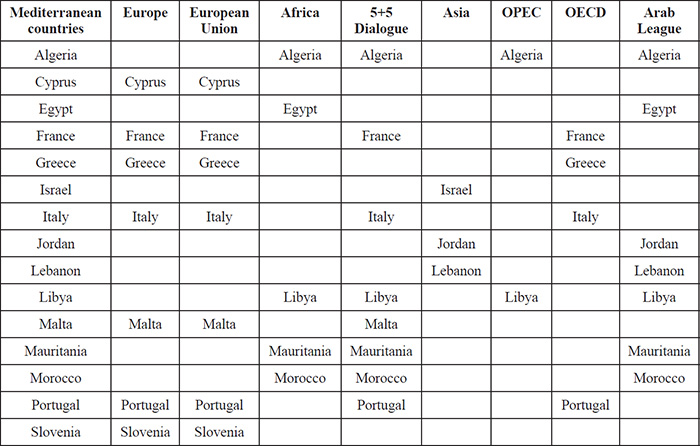

We use two sets of countries. The first set contains our main focus, the Mediterranean countries (Table 4.1); the second one contains our control sample, formed by EU countries (Table 4.2).

Our set of Mediterranean economies covers 19 countries: Algeria, Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Malta, Mauritania, Morocco, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Syria, Tunisia and Turkey. Some Med countries are excluded because of data unavailability. Table 4.1 divides them in different but partially overlapping groups. Nine countries are European, six African, and four Asian. Eight countries are members of European Union (EU); ten belong to the ‘5 + 5 Dialogue’, an inter-governmental association, and nine to the Arab League.29

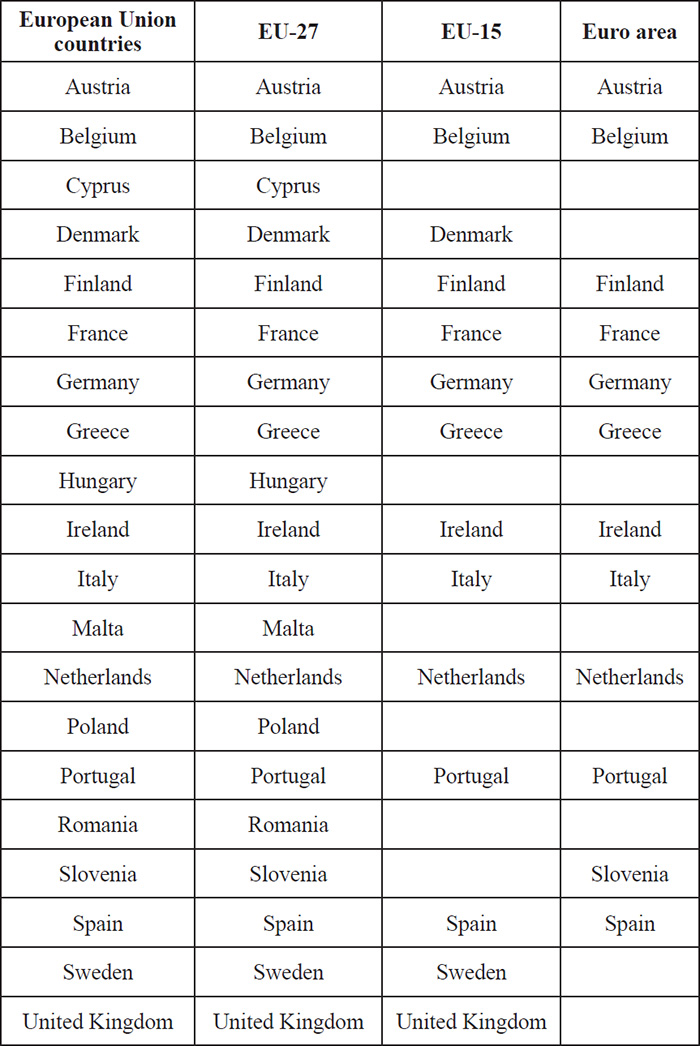

The control sample is composed of 20 out of 27 European Union countries.30 For a better understanding of convergence between Mediterranean countries, it is useful to compare their results with those of European nations that can reasonably be expected to show a higher degree of convergence. Seven countries are included in both datasets: Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal and Spain.

Our source is the International Monetary Fund (IMF) database that collects national statistics. Our variables of interest Yit are two typical indicators of banking development: deposits and loans on GDP. To provide a more complete analysis and to compare our results with those of preceding literature, we compare banking convergence with per capita income convergence. Therefore we apply the methodologies described in the equations (3.1), (3.2), (3.6) and (3.7) alternatively to per capita income, deposits on GDP and loans on GDP.

Deposits and loans exclude interbank transactions, because we are interested in the relationship between banks and their final customers, namely households and non-financial firms. We insert in the exercises on conditional β-convergence some control variables typically used in the literature: official exchange rates with US dollar, inflation rates, banknotes in circulation, volumes of exports and imports. Legal origin is not included as a control variable because most of the Med countries have a French institutional framework.31

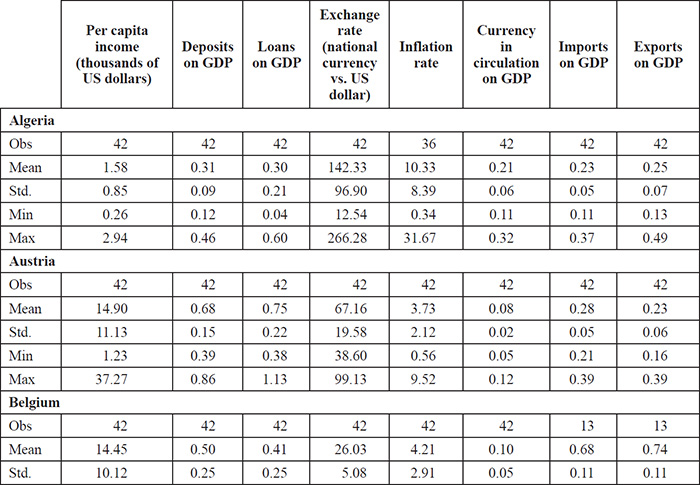

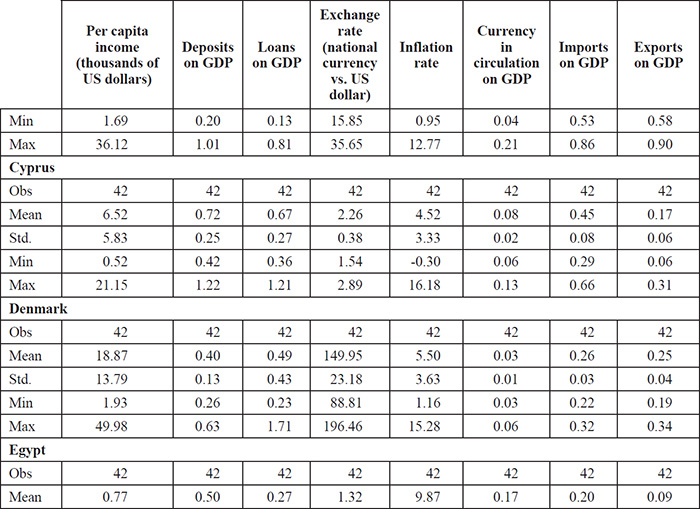

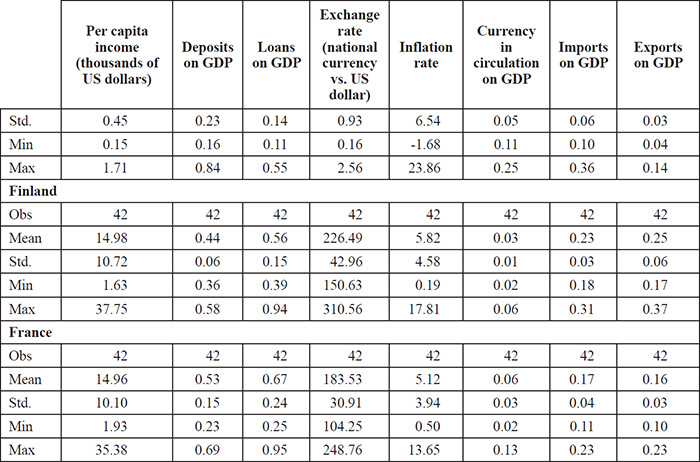

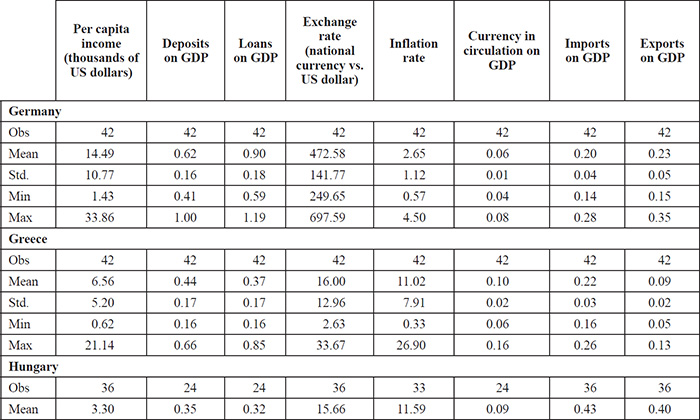

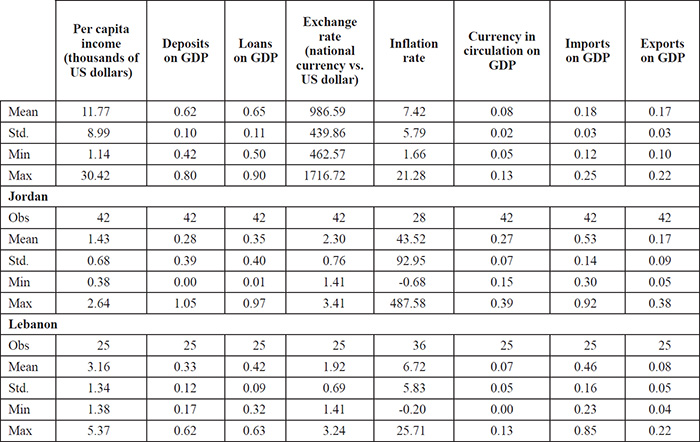

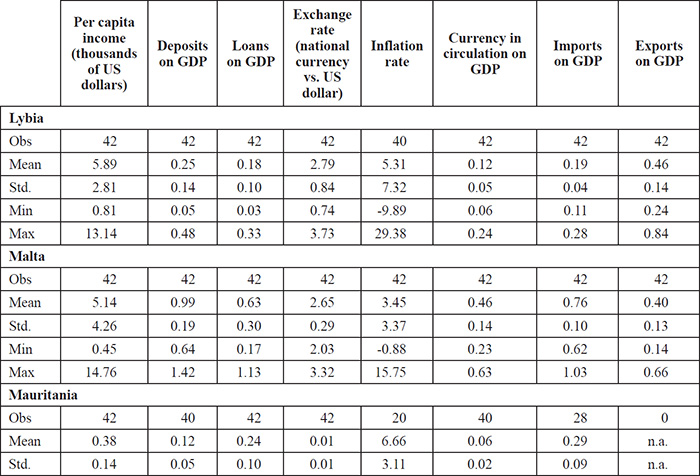

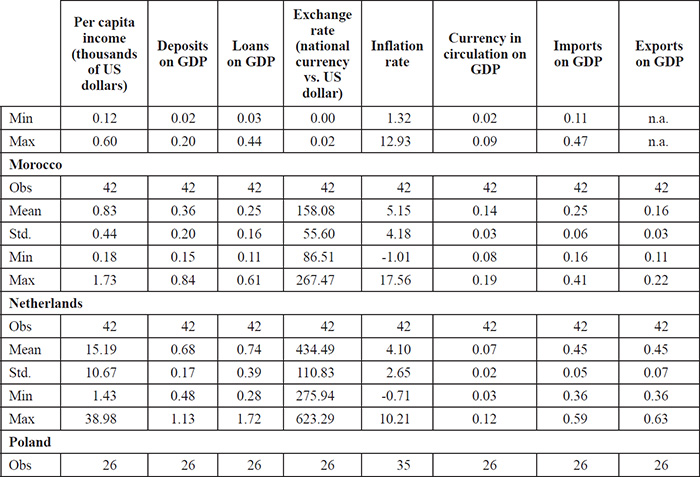

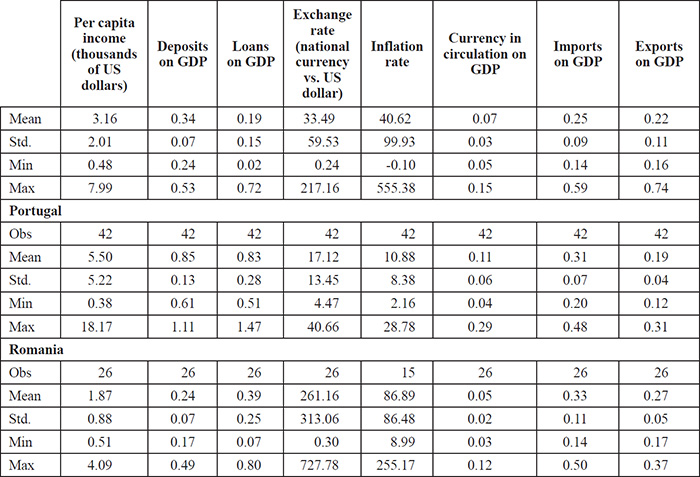

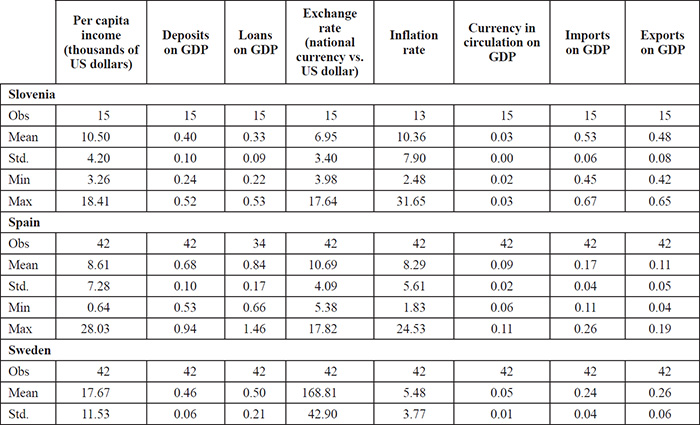

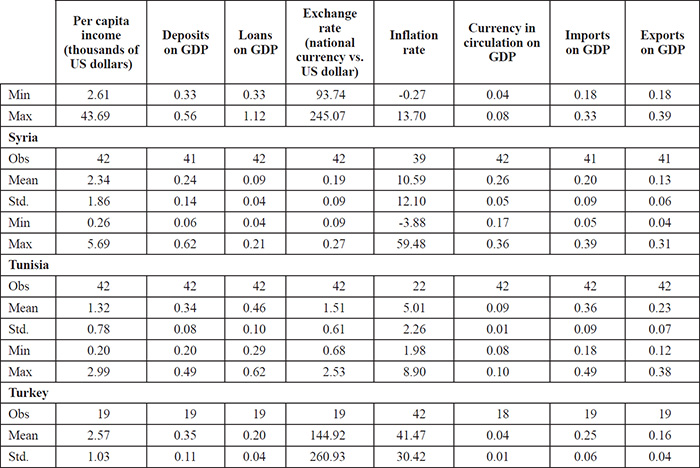

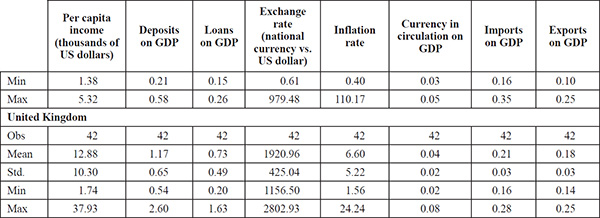

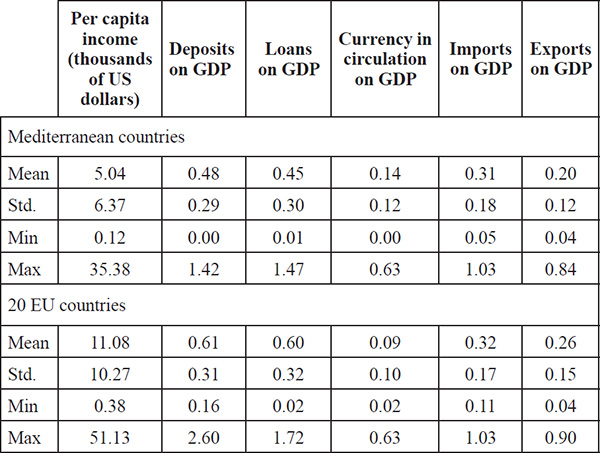

We collected, where available, annual data from 1964 to 2005 (42 periods for each country). The first year was chosen because it is from 1964 onwards that the series are available for the bulk of countries. Table 4.3 provides summary statistics. Data exhibit a significant variability across countries; moreover, the average of each country is affected by the different depth of national time series.32 The statistics are more readable in Table 4.4, where data are assembled for our two groups of countries: the Mediterranean and the EU countries. As expected, Mediterranean countries present lower average values for the three variables of interest: per capita income, deposits and loans on GDP. However, it is interesting that even standard deviation, and then dispersion, is higher for the EU economies than the Mediterranean ones. This confirms that the analysis needs more sophisticated statistical tools.

Following Islam (1995), we split our entire sample period, 1964-2005, into shorter time intervals, averaging our observations over these intervals.33 This procedure makes it possible to level measurement errors, to abstract from business-cycle fluctuations, and to decrease the data serial correlation. The length of the intervals was chosen in such a way as to define three periods of equal length and with an adequate number of years: 1964-77; 1978-91; 1992-2005. Indeed, this choice allows us both to obtain a suitable number of observations and to enhance the long-run notion of convergence.34 Shorter intervals may be subject to short-term disturbances; moreover too-frequent spans could be biased in favour of finding convergence.35 Therefore, we have three time intervals for each country, and the values of all variables are averaged over each period. For the same reasons and to avoid an excessive sensitivity to the first period values, initial levels of variables are computed as averages over the previous period.

In terms of equation (3.1), t° are the time spans 1978-91 and 1964-77; T are the time spans 1992-2005 and 1978-91;  are average growth rates of dependent variables, alternatively per capita income, deposits on GDP and loans on GDP, for the periods 1992-2005 and 1978-91;

are average growth rates of dependent variables, alternatively per capita income, deposits on GDP and loans on GDP, for the periods 1992-2005 and 1978-91;  are the initial average values of the dependent variables, in the periods 1978-91 and 1964-77 respectively; Xit are the average values of other regressors, in the periods 1992-2005 and 1978-91 respectively. In symmetrical fashion, we divided the total period in the same three time intervals for σ-convergence analysis as well. We computed the averages of the three dependent variables for each country over each period, and then the cross-section standard deviations. On the contrary, stationarity tests, our second methodological approach, use all the available yearly observations.

are the initial average values of the dependent variables, in the periods 1978-91 and 1964-77 respectively; Xit are the average values of other regressors, in the periods 1992-2005 and 1978-91 respectively. In symmetrical fashion, we divided the total period in the same three time intervals for σ-convergence analysis as well. We computed the averages of the three dependent variables for each country over each period, and then the cross-section standard deviations. On the contrary, stationarity tests, our second methodological approach, use all the available yearly observations.

5 Results

We present our empirical results according to the two methodological approaches described in Section 3.

First Approach: β-and σ-convergence

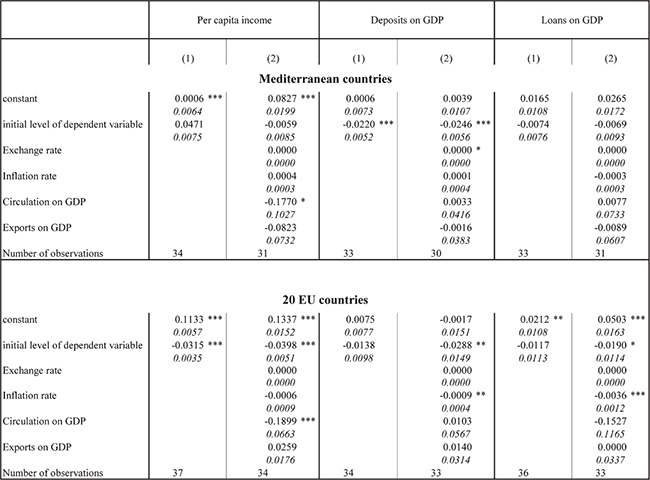

To obtain the β coefficients, we implemented a pooled regression for per capita income, deposits on GDP, and loans on GDP respectively (Table 4.3).36 The upper panel of the table shows the results for the Mediterranean countries; the lower panel reports the results of our control sample, formed by the EU economies. The table contains two specifications. The first specification does not contain regressors, initial levels apart, and corresponds to the test of absolute β-convergence. The second specification reports four covariates, the same for the three dependent variables, and represents a test of conditional ß-convergence.37

As regards per capita income, convergence exists only among EU countries, while Mediterranean countries do not present even conditional convergence. This result is coherent with the prevailing empirical literature, which found robust convergence only in the data of developed industrialized economies, while mixed results were obtained including emerging countries in the regressions.38

For the banking indicators, the two groups of countries seem to converge to similar levels with regard to the ratio between deposits and GDP; while the β coefficient is negative but not statistically significant for loans on GDP. Only for the EU countries, and once structural differences are controlled for, the correlation between initial level of loans on GDP and their subsequent growth rate becomes negative.

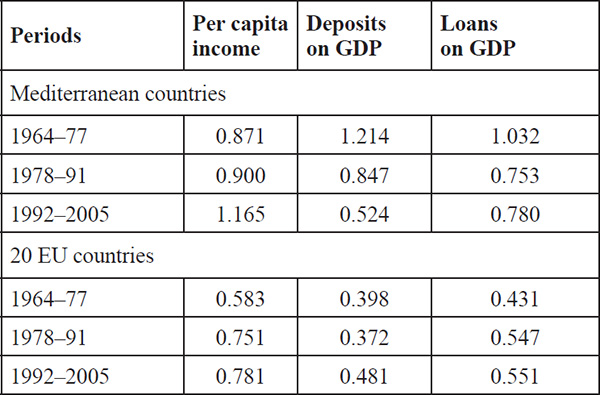

These results are partially different in the σ-convergence analysis (Table 4.5). In this case, there is no σ-convergence in per capita income, not even for the EU-27 countries. Regarding banking indicators, presence of σ-convergence is evident for Mediterranean countries, while it is absent for the EU economies.39 As noted, the two measures of convergence grasp two different aspects. Taken together, we can conclude that, even if the EU economies are regressing to the mean, they are still characterized by the same initial dispersion. On the contrary, although Mediterranean countries present conditional ß-convergence only for deposits, their cross-section dispersion is decreasing for loans too. However, dispersion remains higher, as expected, in the Med area than in the EU countries. Further indications can be achieved using our second methodological approach.

Second Approach: Tests of Zero Mean Stationarity

Our second approach confirms the main results of the first one. As argued in Section 3, we distinguish the tests according to equations (3.6) and 3.7): first, we analyse the differentials Ditj between all the pairs of countries; then, following Baumol’s idea of convergence clubs, we test the differentials DAit between each country and an average of countries belonging to a certain group.

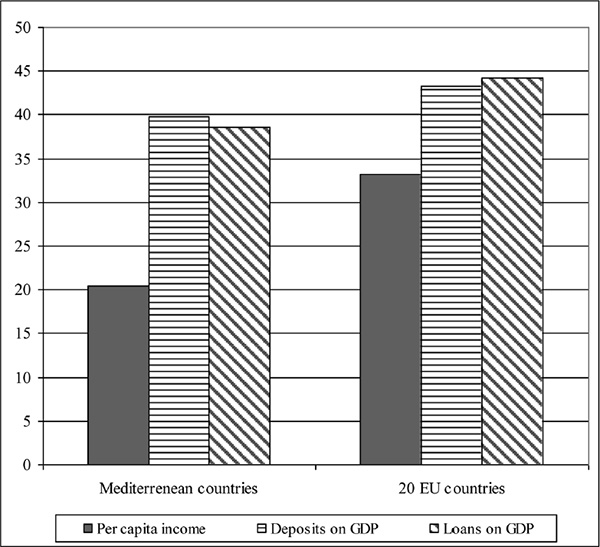

In order to ease interpretation of the results, following Affinito and Farabullini (2007), we do not show all the tests on each pairwise differential, but we present for each variable the percentage share of convergent differentials on the total number of differentials.40 For example, the total number of differentials between all the pairs of 19 Mediterranean countries is 19 (19 – 1) / 2 = 171. The number of convergent differentials, i.e. the number of differentials resulting in zero-mean stationary processes after we applied the ADF and KPSS tests at 5 per cent significance level, is 35 for per capita income, 68 for the ratio of deposits and 66 for the ratio of loans to GDP; accordingly, convergent differentials are, respectively, 20.5, 39.8 and 38.6 per cent of the total.

Figure 4.1 shows these results for, respectively, per capita income, the ratios of deposits and loans to GDP, for the Mediterranean and the EU countries. Figure 4.1 emphasizes that convergence is always higher for the two banking indicators than for per capita income; and it is always stronger in the EU than among Mediterranean countries. However, Figure 4.1 signals that some convergence exists in the Mediterranean basin too. Accordingly, the last step of our analysis is to examine among which groups of countries such convergence emerges.

Our second approach allows us to identify the separate clusters, if any, existing between the Mediterranean countries. We analyse whether a group of countries is particularly similar and then whether convergence within it is more marked. Baumol (1986) coined the term convergence club to express this phenomenon.41 Since the classification itself can be arbitrary, empirical literature raised the question of the identification of the different groups in order to prevent self-selection bias.42 We classify our 19 Mediterranean countries on the basis of their geographic contiguity or membership in international organizations, as shown in Table 4.1. In addition to the group formed by all the Med countries, we consider four sufficiently large groups: Asiatic and African countries, the EU nations and the Arab League ones.

The basic difference compared to previous exercise is that the differentials  are computed on the average of countries in the same group. Therefore, the averages

are computed on the average of countries in the same group. Therefore, the averages  can be seen as steady states where countries could converge. If all the countries of a group converge to their average

can be seen as steady states where countries could converge. If all the countries of a group converge to their average  , then homogeneous model of development could emerge between them and should be grasped by

, then homogeneous model of development could emerge between them and should be grasped by  .

.

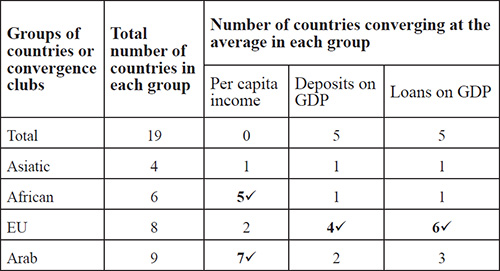

Table 4.7 summarizes the results. The first two columns report, respectively, the groups of nations and the total number of countries belonging to each group, corresponding to those of Table 4.1. The rest of Table 4.7 shows the number of countries converging at the average in each group, for the three variables analysed.43

As expected, the convergence is higher within each group than among Mediterranean countries as a whole. Per capita income convergence is particularly strong among Mediterranean African countries (five out of six) and among Mediterranean Arab countries (seven out of nine). On the other hand, the EU countries are the most similar when the two banking indicators are taken into account (four and six nations out of eight).

6 Further Comments and Conclusions

Exploiting the wide literature on nominal and real convergence, this paper has studied the convergence of banking indicators in the Mediterranean. In this area we included 19 European, Asian and African countries for which long time series are available. We compared banking convergence with convergence of per capita income, using a set of 20 European Union countries as control sample. Seven of them – Cyprus, Malta, Portugal, Spain, France, Greece and Italy – belong also to the Med area.

To study convergence, which is a long term concept, the chapter assembled a large dataset starting from the Sixties. The econometric exercises applied the concepts of beta and sigma convergence, on the one hand, and used stationarity tests, on the other. We also tried to detect the existence of convergence clubs, i.e. subsets of countries that are more similar than the Med nations as a whole. Convergence has been studied analysing the ratio of deposits to GDP and the ratio of loans to GDP, typically used by the literature as proxies of banking system sizes. We obtained three principal results.

First, in the 19 Med countries there are signals of convergence of banking indicators, particularly for deposits. This result derives from a smaller use of currency in circulation as means of payment. Poorer countries of the Mediterranean replicated what happened in richer countries in the past. Also the recent increase in remittances in the Med area, an important element of global capital flows, might be part of the story.44

Convergence is weaker for loans. There are several factors that make convergence of the ratio of loans to GDP difficult: the Mediterranean countries differ in size of firms, dimensions of stock exchanges in terms of capitalization and number of quoted corporations, firms’ securities issued and the role of subsidized lending.45 Path dependence matters for loans.

The Med area banking convergence is weaker than that observed in the 20 European countries. This result confirms the expectation that the European banking systems are more homogeneous, owing to the harmonized financial regulation, the convergence criteria imposed by the Maastricht criteria, the single market and the common monetary policy. Our evidence is more in favour of European banking convergence than the past literature summarized in paragraph 2. A possible explanation is that this is the first work, as far as we know, covering statistics for 40 years. Previous research considered shorter time intervals, facing the problems raised in the convergence debate, first of all the business-cycle effect.

Second, per capita income convergence did not take place in the Med area, while there is evidence of it in the 20 EU countries. Other studies too have found that real convergence was achieved in OECD countries but not in a larger set of countries that includes emerging economies. There is a large debate on the difficulties in finding empirical confirmation to the neoclassical theory of per capita income convergence for whatever group of countries.

Third, splitting the Med area in smaller sets of countries, we found convergence clubs. According to Baumol, the idea of convergence clubs may be more fruitful than the notions of absolute and conditional convergence in larger sets of nations. We obtained two convergence clubs for real convergence, represented by African and Arab countries, while banking convergence was confirmed for the Med EU nations.

Table 4.1 The Mediterranean countries in authors’ dataset and their classification on the basis of geographic contiguity or membership in international organizations

Table 4.2 The European Union countries in authors’ dataset and their classification

Table 4.3a Summary statistics for the country variables in authors’ dataset

Table 4.3b Summary statistics for the country variables in authors’ dataset

Table 4.3c Summary statistics for the country variables in authors’ dataset

Table 4.3d Summary statistics for the country variables in authors’ dataset

Table 4.4 Averaged summary statistics for the two groups of countries in authors’ dataset

Table 4.5 β-convergence of per capita income, the ratio of deposits to GDP and the ratio of loans to GDP for Mediterranean and EU countries

Note to Table 4.5: The table contains the coefficients of pooled regressions for three dependent variables: per capita income, the ratio of deposits to GDP and the ratio of loans to GDP. In all the exercises the average growth rate of the dependent variable is regressed on its initial level (see equation 3.1). The average growth rate for the period 1992–2005 is regressed on the average value of the years 1978–91. The average growth rate for the period 1978–91 is regressed on the average value of the years 1964–77. Columns (1) consider absolute convergence, while columns (2) refer to conditional convergence. Robust standard errors are in italic. The symbols ***, ** and * represent statistical significance at the 1, 5 and 10 per cent level.

Table 4.6 Results for σ-convergence analysis on per capita income, the ratio of deposits to GDP and the ratio of loans to GDP for Mediterranean and EU countries

Figure 4.1 Percentage shares of convergent pairwise differentials within Mediterranean and 20 EU countries

Table 4.7 Convergence clubs within Mediterranean countries

The first two columns report the clubs and the number of countries belonging to each group. The other columns show, for the three variables of interest, the number of countries converging at the average in each group. The symbol ü indicates that the number of converging countries is equal or greater than 50 per cent.

1 We would like to thank, without implicating, for help and comments, Juan Carlos Martinez Oliva, Matteo Piazza, Miria Rocchelli, Luigi Federico Signorini, Andrea Silvestrini and participants at the conference ‘Banking and Finance in the Mediterranean. A Historical Perspective’ held in Malta (June 2007); at the seminar held at the European Central Bank (Frankfurt, November 2007); at the 16th International ‘Tor Vergata’ Conference on Banking and Finance (Rome, December 2007); at the Conference ‘7th International Days of Studies Jean Monnet’ (Rabat, June 2008) and at the ‘10th Mediterranean Research Meeting’ (Montecatini, March 2009). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the point of view of the Bank of Italy.

2 See R. J. Barro and X. Sala-i-Martin, Economic Growth (Cambridge, 1995) on the notions of convergence.

3 See, for example, R. Levine, More on Finance and Growth. More Finance, More Growth?, The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, July-August, 2003, pp. 31-16; and P. Aghion, P. Howitt and D. Mayer-Foulkes, ‘The Effect of Financial Development on Convergence. Theory and Evidence’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 1, 2005, pp. 173-222.

4 See J. Dermine, ‘Banking in Europe. Past, Present and Future’, V. Gaspar, P. Hartmann and O. Sleijpen (eds), The Transformation of the European Financial System (Frankfurt, 2003), for a survey.

5 See G. Calcagnini, F. Farabullini and D. Hester, Financial Convergence in the European Monetary Union?, SSRI Working Paper Series, 2022, University of Wisconsin, Madison, 2000.

6 For an analysis of the convergence proprieties of national inflation rates in the euro area see F. Busetti, L. Forni, A. Harvey and F. Venditti, ‘Inflation Convergence and Divergence within the European Monetary Union’, International Journal of Central Banking, 3, 2, 2007, pp. 95-122. The euro has been a source of convergence but also of asymmetries across countries, with reference to real interest rates and extra-euro trade; however the net impact was to increase the cyclical co-movements across countries (see P. R. Lane, ‘The Real Effects of European Monetary Union’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20, 4, 2006, pp. 47-66). See O. De Bandt, H. Herrmann and G. Parigi, Convergence of Divergence in Europe? Growth and Business Cycles in France, Germany and Italy (Berlin, 2006) on business cycles in France, Germany and Italy; A. M. Kutan and T. M. Yigit, Real and Nominal Stochastic Convergence. Are the New EU Members Ready to Join the Euro Zone?, mimeo, 2005, on real and nominal convergence of the new EU members.

7 European Central Bank, Differences in MFI Interest Rates across Euro Area Countries, September 2006, available at www.ecb.int.; M. Affinito and F. Farabullini, An Empirical Analysis of National Differences in the Retail Bank Interest Rates of the Euro Area, Banca d’Italia, Temi di discussione, 589, 2006. M. Affinito and F. Farabullini, ‘Does the Law of One Price Hold in Euro-Area Retail Banking?’, International Journal of Central Banking, 5, 1, 2009, pp. 5-37.

8 V. Murinde, J. Agung and A. Mullineux, ‘Patterns of Corporate Financing and Financial System Convergence in Europe’, Review of International Economics, 12, 4, 2004, pp. 693-705.

9 V. Di Giacinto and L. Esposito, Convergence of Financial Structures in Europe. An Application of Factorial Matrix Analysis, Proceedings of the Conference: Financial Accounts. History, Methods, the Case of Italy and International Comparisons, 2007, available at www.bancaditalia.it.

10 P. Hartmann, A. Maddaloni and S. Manganelli, The Euro Area Financial System. Structure, Integration and Policy Initiatives, ECB Working Paper, 230, 2003.

11 L. Bartiloro and R. De Bonis, The Financial Systems of European Countries. Theoretical Issues and Empirical Evidence, Irving Fisher Committee Bulletin, 21, 2005, pp. 80-98.

12 J. P. Byrne and E. P. Davis, ‘A Comparison of Balance Sheet Structures in Major EU Countries’, National Institute Economic Review, 180, 1, 2002, pp. 83-95.

13 R. H. Schmidt, A. Hackethal and M. Tyrell, ‘Disintermediation and the Role of Banks in Europe. An International Comparison’, Journal of Financial Intermediation, 8, 1-2, 1999, pp. 36-67.

14 M. Bianco, A. Gerali and R. Massaro, ‘Financial System Across Developed Economies. Convergence or Path Dependence?’, Research in Economics, 51, 3, 1997, pp. 303-31.

15 L. Baele, A. Ferrando, P. Hordahl, E. Krylova and C. Monnet, Measuring Financial Integration in the Euro Area, ECB Occasional Paper Series, 14, 2004.

16 The latest empirical studies indicate that the size and capital base of banks are not relevant (see I. Angeloni, A. Kashyap, B. Mojon and D. Terlizzese, Monetary Transmission in the Euro-Area. Where Do We Stand?, Working Paper N. 114, January 2002).

17 D. Dahl, R. E. Shrieves and M. F. Spivey, Convergence in the Activities of European Banks, mimeo, 2006.

18 M. Affinito, R. De Bonis and F. Farabullini, ‘Strutture finanziarie e sistemi bancari. Differenze e analogie tra i paesi europei’, M. De Cecco and G. Nardozzi (eds), Banche e finanza nel futuro. Europa, Stati Uniti, Asia (Bancaria Editrice, 2006). Other studies have noted the resemblance between the German and the Italian banking systems for the reactions to monetary-policy shocks. A summary of the findings of the ECB’s research project on the channels of transmission of monetary policy impulses claimed that ‘The bank lending channel is found to operate significantly in Germany and Italy’ (Angeloni et al., Transmission, p. X). Evaluating the impact on lending of a 1-percentage-point change in ECB policy rates, M. Ehrmann, L. Gambacorta, J. Martinez-Pagés, P. Sevestre and A. Worms, Financial Systems and the Role of Banks in Monetary Policy Transmission in the Euro-Area, Banca d’Italia, Temi di discussione, 432, 2001, p. 40, found that ‘the magnitude of the lending recession is similar in France and Spain, and similar in Germany and Italy’.

19 N. Segfried and M. Encìo, Reform of Monetary Policy Instruments in Mediterranean Countries, ECB, mimeo, 2006.

20 C. Fehlker, Review of Recent Economic and Financial Developments in Mediterranean Countries, ECB, mimeo, 2007.

21 E.g. W. J. Baumol, ‘Productivity Growth, Convergence and Welfare. What the Long-Run Data Show’, American Economic Review, 76, 1986, pp. 1072-85 ; R. J. Barro and X. Sala-i-Martin, ‘Convergence’, Journal of Political Economy, 100, 2, 1992, pp. 22351; N. G. Mankiw, D. Romer and N. D. Weil, ‘A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107, 2, 1992, pp. 407-37; Sala-i-Martin, ‘Regional Cohesion’; K. Lee, M. H. Pesaran and R. Smith, ‘Growth and Convergence in a Multi-Country Empirical Stochastic Solow Model’, Journal of Applied Econometrics, 12, 4, 1997, pp. 357-92. The literature on economic growth analyses the convergence hypothesis pursuing two main goals. First, it tries to discriminate among alternative economic growth theories. Convergence across countries is interpreted as evidence in favour of the neoclassical model in the tradition of Solow. Second, the analysis of economic convergence evaluates whether intra-country and inter-country differences in the distribution of income tend to disappear over time.

22 About conditional convergence, N. Islam, ‘Growth Empirics. A Panel Data Approach’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 100, 4, 1995, pp. 1127-70, argues that ‘convergence is more commonly understood as different countries of the world approaching the same or similar levels of income (i.e., in the “absolute” sense). There is probably little solace to be derived from finding that countries in the world are converging ... when the points to which they are converging remain very different’ (p. 1162).

23 X. Sala-i-Martin, ‘Regional Cohesion. Evidence and Theories of Regional Growth and Convergence’, European Economic Review, 40, 6, 1996, pp. 1325-52, explains the conceptual difference between the two convergence indicators, writing: ‘σ-convergence studies how the distribution of income evolves over time and β-convergence studies the mobility of income within the same distribution’. D. T. Quah, ‘Galton’s Fallacy and Tests of the Convergence Hypothesis’, Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 95, 4, 1993, pp. 427-43, argues that the concept of β-convergence is irrelevant in respect to σ-divergence because the two notions are conceptually different.

24 A. C. Harvey and V. Carvalho, Models for Converging Economies, University of Cambridge – DAE Working Papers, 2002; A. C. Harvey, ‘Trends, Cycles and Convergence’, N. Loayza and R. Soto (eds), Economic Growth. Sources, Trends and Cycles (Central Bank of Chile, 2002).

25 A. Bernard and N. S. Durlauf, ‘Convergence in International Output’, Journal of Applied Econometrics, 10, 1995, pp. 97-108; A. Bernard and N. S. Durlauf, ‘Interpreting Tests of the Convergence Hypothesis’, Journal of Econometrics, 71, 1996, 161-173; P. Evans and G. Karras, ‘Do Economies Converge? Evidence from a Panel of US States’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 78, 3, 1996, pp. 384-8; and E. G. Tsionas, ‘Real Convergence in Europe. How Robust are Econometric Inferences?’, Applied Economics, 32, 11, 2000, pp. 1475-82.

26 D. A. Dickey and W. A. Fuller, ‘Likelihood Ratio Statistics for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root’, Econometrica, 49, 4, 1981, pp. 1057-71; W. R. Bell, D. A. Dickey and R. B. Miller, Unit Roots in Time Series Models. Tests and Implications, Technical Report n. 757, University of Wisconsin, February 1985.

27 See D. Kwiatkowski, P. C. B. Phillips, P. Schmidt and Y. Shin, ‘Testing the Null Hypothesis of Stationarity against the Alternative of a Unit Root. How Sure are We that Economic Time Series have a Unit Root?’, Journal of Econometrics, 54, 1-3, 1992, pp. 159-78.

28 B. Hobjin and P. H. Franses, ‘Asymptotically Perfect and Relative Convergence Productivity’, Journal of Applied Econometrics, 15, 1, 2000, pp. 59-81; Busetti et al., ‘Inflation Convergence’; Affinito and Farabullini, ‘Does the Law’.

29 The ‘5+5 Dialogue’ is an informal forum of ten States from both shores of the Western Mediterranean: Algeria, France, Italy, Libya, Malta, Mauritania, Morocco, Portugal, Spain and Tunisia. These countries meet regularly to strengthen regional consultancy on different issues of common interest. The League of Arab States is a political-economic alliance established in 1945; it is formed of 22 countries around the world.

30 We excluded the following EU countries due to missing or too short series: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Slovakia.

31 On the legal view of finance see R. La Porta, F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. W. Vishny, ‘Law and Finance’, Journal of Political Economy, 106, 6, 1998, pp. 1113-55.

32 Slovenian data are available from its formation in 1991. The Hungarian statistics are available from 1970 for GDP, and from 1982 for loans and deposits. The data for Lebanon, Poland and Romania are available from 1980; those for Turkey from 1987. The series on Spanish loans start in 1972; those on Irish deposits in 1999.

33 Islam, ‘Growth Empirics’.

34 R. Cellini, ‘Growth Empirics. Evidence from a Panel of Annual Data’, Applied Economics Letters, 4, 6, 1997, pp. 347-351; M. Lee, R. Longmire, L. Màtyàs and M. Harris, ‘Growth Convergence. Some Panel Data Evidence’, Applied Economics, 30, 7, 1998, pp. 907-12.

35 Quah, ‘Galton’s Fallacy’; and D. T. Quah, ‘Empirics for Economic Growth and Convergence’, European Economic Review, 40, 6, 1996a, pp. 1353-75.

36 We first run a single cross-section regression, following the method of Barro and Sala-i-Martin. These results are analogous to those of the pooled regression and therefore not reported.

37 In the estimations we used a standard robust regression model that implements a data-dependent method for down-weighting outliers. We ran several specifications and carried out different robustness checks. We progressively introduced the explanatory variables, in order to control for the presence of endogeneity; we substituted, where possible, the single regressors with similar variables. These attempts are not presented owing to the stability of results. The regressors, initial levels of variables apart, are not commented upon because they are not the focus of our analysis.

38 P. Romer, ‘Capital Accumulation in the Theory of Long-Run Growth’, in Robert J. Barro (ed.), Modern Business Cycle Theory (Cambridge MA, 1989); R. G. King and S. T. Rebelo, Transitional Dynamics and Economic Growth in the Neoclassical Model, NBER Working Paper, 3185, Cambridge, 1989; S. Rebelo, ‘Long-Run Policy Analysis and Long-Run Growth’, Journal of Political Economy, 99, 3, 1991, pp. 500-521.

39 As easily demonstrable, if there is no ß-convergence, there cannot be σ-convergence (e.g. Barro et al., Growth). On the contrary, loans on GDP apparently present σ-convergence (Table 4.6, last column) while they register absence of ß-convergence (Table 4.5, last column). The reason is that σ-convergence is present for all our three time spans, while for ß-convergence we miss a time observation when regressing the variable on its initial level. Therefore if we look only at the last two periods also for σ-convergence, then the mathematical rule holds.

40 The detailed results are available from the authors.

41 Baumol, ‘Productivity Growth’.

42 J. B. De Long, ‘Productivity Growth, Convergence and Welfare. Comment’, American Economic Review, 78, 5, 1988, pp. 1138-54; Quah, ‘Empirics’; D. T. Quah, ‘Regional Convergence Clusters across Europe’, European Economic Review, 40, 3-5, 1996b, pp. 951-8.

43 Detailed results of each country are available from the authors.

44 See R. Settimo, The Role of Workers’ Remittances in Mediterranean Countries, paper presented at the Euro-Mediterranean Seminar, Cannes, 9 February 2005. On the link between globalization and convergence see J. G. Williamson, Globalization, Convergence and History, NBER Working Paper, 5259, 1995.

45 See R. De Bonis and F. Farabullini, ‘I sistemi bancari del Mediterraneo’, G. Gomel and M. Roccas (eds), Le economie del Mediterraneo (Rome, 2006) on the banking systems in Southern Mediterranean countries.