Introduction

Overview

The church at Corinth was wracked by problems caused by faulty beliefs, arrogance, and immaturity. The main problem in both letters seems to revolve around the issue of what it means to be truly “spiritual.” An immature understanding of true spirituality (pride in spiritual experiences, feeling they have arrived spiritually, factionalism) led to a variety of problems within the church. In 1 Corinthians Paul deals with these local church issues. After Paul wrote 1 Corinthians, his relationship with the church deteriorated. Apparently, Paul’s opponents had been able to turn a portion of the church against their apostle. Because the church is now divided about the legitimacy of Paul’s apostleship, he must defend his apostolic authority, which he does in 2 Corinthians. Paul’s goal in defending himself and the message he preaches is to defend and strengthen the Corinthians’ faith.

Date, Occasion, and Major Themes

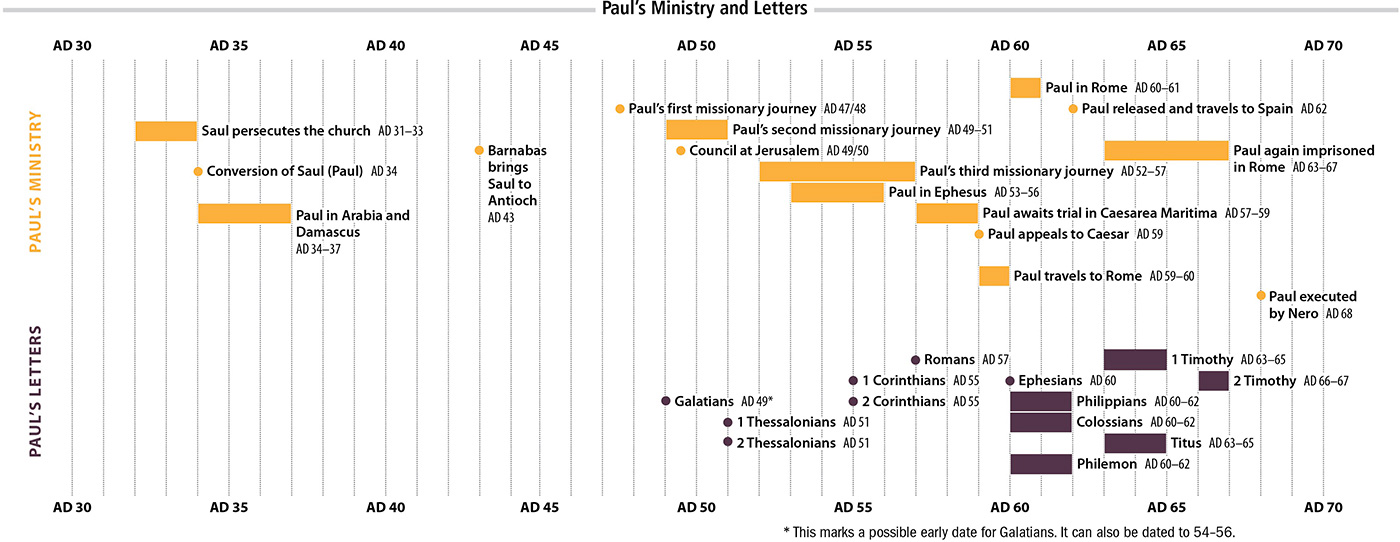

First Corinthians was sent some months before Pentecost in AD 55 (for more on Paul’s relationship to the church at Corinth, see the introduction to 1 Corinthians). At that time, Paul’s plan appears to have been to return within the year to Corinth as his final stop on a journey through Asia Minor, Macedonia, and Achaia (1 Co 4:18–21; 16:5–9). Shortly after 1 Corinthians was sent, however, the apostle changed his plans and decided to make his journey to Macedonia by beginning and ending with a visit to Corinth (2 Co 1:15–17). Intervening events made Paul modify his plans a third time following his visit to Corinth (the second visit of 2 Co 13:2), and on his subsequent journey through Macedonia, he did not return to Corinth as he had originally promised he would (2 Co 1:23).

At least two of the reasons for this final change of plans become apparent in 2 Corinthians. First, Paul’s second visit to Corinth was not at all as he had hoped it would be. Instead, it had involved him in a number of exceedingly painful (2 Co 2:1) confrontations in which, according to Paul, both the Corinthians (2:2) and he himself (2:5) suffered grief. As a result, from somewhere along the way through Macedonia, Paul wrote a letter to pointedly express his “troubled” and anguished heart at the distance that had developed between him and some of the Corinthians, and sent it off with Titus.

Second, upon reaching Asia at the close of his journey, Paul was beset by “affliction” and pressure associated with a peril so deadly that he “despaired of life itself” (2 Co 1:8–10). In the midst of such an experience, it would have been impossible for him to return to Corinth, even if he had desired to do so. Nevertheless, having been rescued from death by God’s grace, and having reached Troas once more, Paul was anxious and without peace of mind apart from news of the Corinthian response to his last letter (2 Co 2:13). Accordingly, he pressed on into Macedonia, hoping to meet Titus. Their meeting took place a short time later, and, as its result, Paul wrote 2 Corinthians from somewhere in Macedonia (2 Co 7:5–7, 13–16).

Literary Unity

Although the preceding reconstruction of events represents something of a consensus among interpreters, there is nonetheless a considerable diversity of opinion about the literary integrity of 2 Corinthians and the precise historical background that might have occasioned the composition of 2:14–7:4; 8:1–9:15; and 10:1–13:14. Indications exist that suggest these texts may not have been written at the same time as the rest of 2 Corinthians.

With respect to 2 Co 2:14–7:4 and 8:1–9:15, the evidence is slight. For while it is true to say that 2:14–7:4 represents something of an intrusion into the narrative account that begins with 1:8–2:13 and concludes with 7:5–16, such a parenthetical and digressive intrusion is not uncharacteristic of either Paul’s literary style or his Corinthian correspondence. (One may compare, for example, 1 Co 9:1–27, which intrudes into an apostolic reply that begins with 8:1–11 and concludes with 10:1–11:1.) Similarly, it has often been noted that there is an abrupt transition in the flow of 2 Corinthians as one moves from 7:16 to 8:1 and a surprising reiteration of subject as one moves from 8:24 to 9:1. Upon further reflection, it may be seen that the abrupt transition is related to an important change of topic, and that reiteration of a principal subject, in this case the “ministry to the saints” (9:1), is once more a characteristic of Pauline literary style.

It is more difficult to make a definite decision about 2 Co 6:14–7:1. The lack of any reference to the immediate historical situation, the logical and literary links—which are apparently restored when 7:2 is read immediately after 6:13—and the concepts and vocabulary that are used in the passage argue that this text may have been a part of the letter that Paul affirms he wrote to the church prior to 1 Corinthians in order to advise them “not to associate with sexually immoral people” (1 Co 5:9). If that is true, then perhaps an individual, unknown to us, collected and edited Paul’s Corinthian correspondence and inserted this section into 2 Corinthians. That person may have been unsure of its proper place in the sequence of Paul’s letters to Corinth, or perhaps it seemed appropriate, despite its historical origins, to read this text in conjunction with the message of 2 Corinthians. On the other hand, however, it is possible that Paul may himself have felt a need at this point in the letter to remind the Corinthians of his previous counsel, and in doing so, chose to make use of thoughts and perhaps even words drawn from his memory of the earlier letter.

A decision in favor of literary integrity becomes most difficult, however, when one considers the evidence with respect to 2 Co 10:1–13:14. For while earlier parts of the letter show clear signs of having been written in a conciliatory spirit, at a moment when Paul sought to commend the Corinthian Christians and gratefully acknowledge their renewed affection for him (1:7; 2:5–11; 6:11; 7:2–4, 7, 13), the spirit of 10:1–13:14 is profoundly critical. This section contains numerous indications that these chapters were not occasioned by an effort to effect harmony between the apostle and his converts but instead were written by Paul in an attempt to defend his rightful apostolic authority against all those in Corinth who might attempt to deny it (10:5–8; 11:4–6, 12–16; 12:11–13; 13:1–3). Furthermore, on two occasions in the latter part of the letter (i.e., 12:14 and 13:1), Paul speaks about a third visit he is about to make, but in the earlier portion of the letter he fails to mention it even where one would expect such a reference (i.e., 1:15–2:13). Finally, in 12:18 Paul writes as though the mission of Titus announced in 8:16–24 has already been completed.

Given such evidence, one could propose a set of circumstances that might still enable one to maintain that 2 Co 10:1–13:14 was written at the same time as 2 Co 1:1–9:14; or one could construct a different set of circumstances that might enable one to conceive of 2 Co 10:1–13:14 as a part, if not the whole, of the letter written “with many tears out of an extremely troubled and anguished heart” (2:4) immediately prior to 2 Co 1:1–9:14. However, the simplest explanation of the scriptural evidence points to the conclusion that 2 Co 10:1–13:14 is a part of a letter written sometime after the composition and dispatch of 2 Co 1:1–9:14. Of the letter’s reception, and of the subsequent relationship between Paul and the church at Corinth, we know far less than we might like. But, comparing Rm 16:23 with Ac 20:2–3 and 1 Co 1:14, we may infer that once again the letter of the apostle had a salutary effect, enabling him to make his promised third visit to Corinth, at which time he composed his letter to the Romans while residing in the house of Gaius, his convert (Rm 16:23).

Outline

1. Epistolary Introduction (1:1–11)

2. Paul’s Explanation of His Conduct in Recent Matters (1:12–2:13)

A. The Basis for Paul’s Behavior and an Appeal for Understanding (1:12–14)

B. The Cause for Paul’s Change of Plans (1:15–2:2)

C. The Purpose of Paul’s Last Letter (2:3–11)

D. The Motive for Paul’s Movement from Troas to Macedonia (2:12–13)

3. Paul’s Reflection on His Ministry (2:14–5:21)

A. The Source and Character of Paul’s Ministry (2:14–3:6a)

B. The Message of Paul’s Ministry (3:6b–4:6)

C. The Cost of Paul’s Ministry (4:7–5:10)

D. The Perspective of Paul’s Ministry (5:11–21)

4. Paul’s Appeal to the Corinthians (6:1–13:10)

A. An Appeal for Complete Reconciliation (6:1–7:4)

B. A New Basis for Appeal (7:5–16)

C. An Appeal for Full Response to the Collection (8:1–9:15)

D. An Appeal for Full Allegiance to Apostolic Authority (10:1–18)

E. Support for the Appeal (11:1–12:13)

F. The Conclusion of the Appeal (12:14–13:10)

5. Epistolary Conclusion (13:11–14)