I NEVER FOR A MOMENT dreamed I’d be back. I keep telling people my life has turned around 360 degrees. Someone said, “You mean 180 degrees.” But I said, “No, I mean 360. It has come full circle.”

In the spring of 2009, while I was still working on this book, I got a call from the North Stars, the senior men’s team in Steinbach, Manitoba, asking me if I’d be interested in playing for the Allan Cup again. So there I was, back on the prairies in November, and it was minus-60. Kind of like déjà vu. The conditions were harsh. People ask me where I developed this toughness from. My answer? Winters in Manitoba. There were no parents tying skates, no rock music playing in between periods, no Starbucks coffee mocha latte whatever. Remember how I told you about the curling rink where I first got started? Basically, some parents got together, threw some boards up, and there was our rink. Just an old tin shed. It was natural ice, real—like the hockey.

In Steinbach, I found my love for the game again, and it was exhilarating. I was seeing the ice the way I used to—in the moment. Obviously, I wasn’t playing against NHL competition, but I was still making good plays: saucer passes through three or four sticks, hitting guys full stride, taking it in and sniping. I got home and said to Jenn, “Man, I missed this.”

The whole getting-sober process was like listening to one of those hurtin’ country songs backward. I got my kids back, got my dog back, got my truck back, got my life back. Beaux and Tatym were trusting me and opening up more. Beaux’s a very quiet individual, but he feels things deep. We were driving somewhere and he said to me, “Dad, I just wish that I was older and had been able to see you play.” I felt something pull inside.

Writing this book made me look at all the negative stuff at the end of my career. For the first time in my life, I admitted to myself, “I’m kind of ashamed.” I wanted a chance at the Hockey Hall of Fame. But I knew if I didn’t get reinstated, and change the way I was perceived, there would always be this stigma over my head. I had to clear my name, but how?

A comeback.

I was sitting at the kitchen table one night in February when I said to Jenn, “What do you think about me making a comeback to the NHL?” She just started laughing. The thing with Jenn is that none of my ideas surprise her at all. She just kind of goes with the flow and supports me in whatever it is that we’re doing.

The first thing I did was meet with a trainer, Mike Porter, and told him I really needed to get into shape. At 215 pounds, I was probably 25 per cent body fat. I told him I didn’t know where all this was going to end up, but I just needed to see if I was willing to pay the price again. The first couple of weeks weren’t a whole lot of fun. I felt like Rusty the Tin Man. I needed some oil.

It took about forty days before muscle memory started to kick in, but once it did, I could work out and not avoid sitting down to take a shit the next day.

The second thing I needed was to learn to use my head, so I took up Pilates with Steph Davis. Steph works with her husband, Scott Davis, the U.S. national figure skating champion in 1993 and 1994. Scott skated at the 1994 Olympics and is now a coach. So Steph knew my mentality. And she has lots of experience with hockey players, including Marty Gélinas, Rhett Warrener and Oiler goalie Devan Dubnyk. When I went into the gym, it was pretty easy to lift the weight without thinking about it much, but with the Pilates, mind and body have to become one and work together. At the beginning, I thought, “Oh yeah, this is bullshit,” but as time went on, I noticed it was tougher for guys to move me off the stick. All of a sudden I had this new core strength. At 41 years old, this was going to give me an edge.

Now, this next part is hilarious, and shows you what an alcoholic I am. I figured I could just call Gary Bettman on his personal cell phone and say, “Hey Gary, you know what? I’ve been working out, my life is straightened around, I’ve got four years of sobriety, so I need you to reinstate me.” And he would say, “Oh yeah? Good for you, no problem.”

This is how the real phone call went: “Hey Gary, it’s Theo Fleury. I’m thinking about going through the process of reinstatement.” Silence, then, “Call the doctors.” Click.

I met with Dr. Shaw and Dr. Lewis in Denver at the airport on July 9, 2009. The last time I saw Dr. Lewis, it wasn’t a good scene. I believe I had him up against the wall by the throat and was threatening to tear his fuckin’ head off. But he seemed genuinely happy to see me sober. Both docs grilled me. “What have you been doing? What’s going on with your life?”

I told them, “I’m four years sober, I’m newly married, I have a beautiful baby daughter born September 7, 2008. Her name is Skylah Mary Anne Fleury. She looks just like me.” “How’s the relationship with the other kids?” “Amazing,” I said. “They actually want to spend time with me and they like me again.” At the end of that meeting, they said they were going to recommend me for reinstatement and that they would contact me to make it official. I was like, “Whoa, that’s pretty exciting stuff.” I called Jenn and we were both crying.

It was five weeks before training camp, and I had no clue of where I was fitness-wise. So Jenn called TCR Sport Lab in Calgary. The owner, Cory Fagan, who has two kinesiology degrees from the University of Calgary, is an exercise physiologist. I went in and he gave me a VO2 test. Cory knew what kind of numbers an NHL team needed to see. The minimum was a score of 50. When I was peaking with the Rangers, I was in the 60s, and I even reached 70 at one point. Cory explained that this was because I had the aerobic engine of a cross-country skier. I’ve got a big heart and lungs, so when I’m in top condition I use the oxygen I breathe super efficiently.

There are two reasons why some hockey players can be double-shifted. One, they’re talented. Two, they recover faster than other guys. I can go out there and bust it for a minute, come back to the bench and sit down for a minute, then go back on. When the Flames were shitty during the ‘90s, I led the forwards in ice time for three or four years in a row because I am a genetic freak. Lance Armstrong is a fantastic cyclist partly because he has the same gift. In hockey, so do Phil Housley, Timmy Hunter, Jim Peplinski, even guys like Cale Hulse. Some may not have the same talent, but they have amazing stamina. When you have both, you can become a superstar. The Flames were the first team to run VO2 tests, when Pierre Pagé—or P-Squared, as I like to call him—was around. Pro hockey players are noted for being the best aerobic athletes who don’t know it. They are totally unaware of how good they are in that department.

When I went in to see Cory that first day, I completely fuckin’ bombed. Bombed! My VO2 score was 42.5. Part of the problem was that, at 185 pounds, I was carrying a lot of body weight. That brings the score down. But even if I had been ten pounds lighter, my VO2 still wouldn’t have been more than 47, and that just doesn’t cut it. My body fat was at 15 per cent, compared with under 12 per cent for pros. Basically, if things didn’t improve, I was going to walk into camp with shit on my shoe.

We had six weeks left—only enough time for a crash course. Cory explained that, although hockey players love to do what they’re good at—short, explosive bursts—I needed to do long, slow, endurance-type activities in order to redevelop my lungs. So, for four days a week I dragged myself over to TCR and rode a computerized bike for a couple of hours. Cory’s wife and business partner, Jill Sagan, who was training for a ride of her own, was right beside me, kicking my ass. That is what made it bearable—trying to beat her.

I was put on a strict diet. No sugars, not even gum. Do you realize that if you put a stick of gum in your mouth, your body won’t burn fat? Think about it. When you taste the sugar on your tongue, the body thinks it’s getting sugar, so fat-burning stops until the gum wears off. Some people chew four or five sticks a day. That’s five hours of good fat-burning lost.

I would show up with an empty stomach and have breakfast after. The first couple of workouts, I was kind of light-headed, which I frigging hate. I’d come in and they’d say, “Hey, Theoren!” I would say nothing. Nothing. Head down. “How’re you doing?” they’d ask. I’d growl, “Riding my bike.” From 8 a.m. until 11. I was dropping three to four pounds a day. On the inside, I was panicking. I didn’t want to be embarrassed.

The first couple of weeks of my training went by with no call from the doctors. I was frustrated and anxious. Then I heard from them. They were coming to Calgary for the Olympic orientation camp on August 24, to meet with the athletes going to the Olympics and let them know which over-the-counter and prescription drugs were okay and which were not. They had blocked off a whole day just to hang out with me. I think they were a little bit leery about what was going to be in this book. They were probably wondering if I was going to trash them. I told them, “The book is about me taking responsibility, owning up to everything that I’ve done.”

My former agent, Don Baizley, was skeptical about whether I was ready for a comeback. Everybody was. How many times had I said, “Oh yeah, this time I’ve got it together,” and then, a month later, I was getting wrecked in a strip joint? But Baiz stepped up for me as always. He talked to the NHL Players’ Association, trying to fast-track my reinstatement, and we were making progress with the head guy, Paul Kelly, until he got turfed, or he resigned or whatever happened there.

On Wednesday, September 9, the week before training camp, I was sitting at home, shitting bricks. Then the phone rang. It was the Flames’ GM, Darryl Sutter. “Hey, it’s Darryl here. How’s it going?”

I said, “It’s going good.”

“What’s happening with the reinstatement and all that?”

“I’m just waiting to hear.”

Then he said, “When you get reinstated, would you please give us, the Calgary Flames, the opportunity to invite you to camp?”

Wow! Cool. When I got off the phone, I talked to Jenn, and was very emotional. I will always appreciate that Darryl made that call to me.

I’d been practising on ice with the guys that summer, and it turns out that Cory Sarich had told Darryl something like, “I think you should invite Theo to camp. He looks fucking unbelievable.” Well, what better endorsement can I get than from a fellow player? Trust me, I’m now a big fan of Cory Sarich. I remember playing against him. He’s a competitor, and in 2009–10 he was the only guy in the Flames’ dressing room with a Stanley Cup ring, which he won with Tampa Bay in 2004 in a seven-game final—against the Flames.

I worked hard, really hard, and got myself into the best shape I could possibly be in, but the one thing that was holding me back was a meeting with Gary Bettman. He was busy in court, battling Jim Balsillie over the ownership of the Phoenix Coyotes. I’m sure my problem was as welcome as a boil up the butthole. On Tuesday, September 8, I called Bill Daly, who is the vice-president of the league and Gary’s right-hand man. I said, “Bill, when can we get a meeting?”

He said, “You’re going to have to fly to New York this Monday—September 14.” I was thinking, “Fuck. Training camp starts five days after that.”

A little while later, I got a call back from Bill. “Can you be in Phoenix on Thursday night at seven?” I said, “I’m leaving right now.”

It was 110 degrees in Phoenix on September 10. Don Baizley and a representative from the NHLPA were conferenced in by speaker-phone, and Gary Bettman was sitting on one side of me, with Bill Daly on the other. Gary asked, “So tell me, what have you been up to since 2003?”

When I was in New York, going through all my problems and issues, I’d had a meeting with Gary. At that meeting I felt he was truly concerned with me as a human being as opposed to being the guy worried about putting butts in the seats and selling tickets. So I brought that up. I said, “You know what, Gary, I have to tell you that I’ll always remember that meeting we had together in New York when you showed you really cared about me as a person.” Then I spent about fifteen minutes telling him about how I’d made this transformation. At the end, he gave me the old lie-detector eyes. Guys like him have shovelled a pasture full of other people’s bullshit. Finally, he said, “We’re going to reinstate you. Good luck. I hope to see you on the ice this year.”

And I was like, “Holy fuck. Wow. Wow! Unbelievable. How does a guy go from having a gun in his mouth to NHL training camp!” My eyes were burning. It had been a long haul.

Then Gary asked where was I going.

And I said, “Where do you think I’m going? I will be pulling up to the Saddledome Saturday morning.”

I got to camp and I looked great. Fuckin’ lean, ripped, cut. But nobody was really interested, right? It was a lot like the day I showed up twenty years earlier, and everyone said, “What the fuck are you doing here?” So here I was, having to prove myself all over again.For the first couple of tests, the coaching staff and Rich Hesketh, my old trainer who is now the Flames’ fitness guy, came around to watch me. I did a couple more tests and more guys gathered around. After a couple more, there was a bit of a crowd. Finally, while I was doing the VO2 test on the bike and absolutely just fuckin’ blowing it out of the water, I had their full attention. I had come up eighteen points in my VO2 and dropped to 8 per cent body fat. Rich pulled my old results and said, “Your outcome today is better than when you played. How’d you do it?” How did I do it? A God shot. That’s what I’d call it.

Right from the first skate, I noticed the dressing room had changed. Big time. It was like walking into a penthouse. There was a kitchen in there—a fuckin’ kitchen! I could walk in and have breakfast. In the old days, it was Timmy Hortons drive-thru and three cigarettes on the way to the rink. Maybe I’d eat a PowerBar when I got there. But now, there were two waiters, waiting hand and foot on the guys—hard-boiled eggs, oatmeal, fruit and yogurt, juice, coffee, whatever. And then there was the new players’ lounge. How did it compare to the old one? It didn’t. We used to pull up a piece of carpet in a bare room, and you were lucky if there was enough pizza left by the time you got out of the shower.

The new place had enough bikes for every guy, and after the game, everybody chose a workout from the board. In the old days, I would have said, “Fuck that, I’m going to the bar, see you guys later.” That is unacceptable today. When I played, it was more fun. We were looser, and that made us tighter as a team. But the level of fitness today is insane, and that is why players have such speed and endurance. I have to hand it to today’s players. They work hard and a lot of the guys are fuckin’ machines.

The social atmosphere is a lot different too. Remember the shoe check? Try pulling a prank on NHLers today and it would not go over. It’d be like farting at a bridal shower. The Sutters like intensity.You do not jack around. It’s all business, all the time. Besides, most guys are too sensitive now. They’d take it too personally. If I had put baby powder in the blow dryer, it would have been considered “offensive”—infringing on someone’s space. One or two of the guys would be rattled for the rest of the year. They might not be able to play hockey, they’d be so upset.

It’s because the money is so big. There is so much competition for that money. How many kids play hockey in Canada? A million? Worldwide? Five million? All them trying for seven hundred jobs. That’s why you see 12-year-olds with trainers and nutritionists.

Players today are a product of that generation—they’re systems kids. Everything is arranged. They don’t play enough on outdoor rinks, so that skill, that natural ability, just doesn’t come out. It stays dormant. If a player tries to beat somebody one on one, he gets shit from the coach. “Get over the red line, dump it in, chase!” Why would you dump it in if you already have it? That never made sense to me, ever. It’s like Sergei Makarov used to say: “Keep’m puck! Keep’m puck!” If we were having a power-play meeting, he’d be like, “Why you shoot puck in? We got puck! Keep puck.” At training camp, my natural inclination was to go with my instincts. If I had the puck in the neutral zone and I looked up and Dion Phaneuf was there, I’d take him on one on one, but if it were Nick Lidström, I’d dump it in. In today’s NHL, that is the wrong mentality. No one sees Phaneuf, no one sees Lidström. All they know is, “I got the puck over the red line, now dump it in. Okay, let’s chase after it.” Players are not allowed to think. When they come in there’s breakfast, and then there’s lunch. Because if lunch is not provided, you have to decide where to go eat, and that is just too fuckin’ hard.

We had an hour practice, and that was it. What we used to do was scrimmage, and there were ten to twelve fights each time. In 1989, when I went to training camp, I had to work my nut sack off to try to beat Otto, Nieuwendyk, Killer and Jirí Hrdina, because if I made it, it meant one of them might lose his job. This time I thought I would get to compete against David Moss and Iggy, but the team had already basically been picked because in a capped world, everybody’s under contract. There is no competition. How many positions can be open when you have fourteen to eighteen guys on one-way contracts?

I was hoping to make the team, but I didn’t know how much had changed in the six years I’d been away from the game—even the way teams handle a losing streak. What should you do when the team is shitting the bed? We used to take everybody out, behind the coach’s back, and party hard, then come in and be like, “Oh crap, what if the coaches find out?” So you’d play hard, play guilty. What do teams do today? The coach arranges for everyone to go bowling. It’s fuckin’ helicopter parenting.

I’ll tell you a story. On September 17, 2009, I was coming off the ice after the first period of the first game that I played, an exhibition game against the Islanders, and the trainer started grabbing for my helmet. I said, “What the fuck are you doing?”

He said, “Oh, we clean the visors now.”

I said, “If you touch my helmet, I’m going to fuckin’ knock you out.” C’mon, I can’t clean my own visor? Are you kidding me? Another example was when we practised and then left to go to Vancouver. You know the drill. Pack your gear, zip it up, throw it onto your shoulder, carry it out to the dolly so that the trainers don’t have to. I think I was the only guy who did it. Everybody else just left their bags there. Wide open, shit lying all around for the trainers to take care of. Unbelievable.

What do they talk about before a game? Well, have you ever heard of the duPont Registry? Look it up online. It is the new hockey player’s handbook. It’s full of fuckin’ million-dollar boats and cars and homes and shit. These magazines for the loaded are all over dressing rooms in the NHL.

Young guys don’t have a fucking chance. When you make that much money, you’re getting bombarded from every angle. It started in my generation, and it’s worse today. All the relatives and old friends crawl out from the cracks. The players are also dealing with the guy who has the trinkets—“You gotta look at this incredible deal, it’s unbelievable! Invest with me and you will never have to worry about money again in your life!” Then the wife gets together with the other wives, who have Prada and Gucci and diamonds the size of donut holes. And she has to show the girls that her husband loves her too. Believe me, there is more than one guy who has three nannies for one kid. It is ridiculous. Birthday parties start to look like most people’s weddings, with bands and fuckin’ caterers. When I turned 30, Veronica threw me a big party at Willow Park Golf Course and presented me with a custom-painted Harley-Davidson 95th Anniversary Heritage Softail, and I thought that was perfectly normal.

Life becomes way more complicated than it needs to be. Instead of driving a nice Ford truck that’s a couple of years old, the player goes out and buys four cars: the Mercedes, the Maserati, the truck and a Cadillac Escalade for the family. The five-thousand-square-foot house isn’t good enough to live in all year round. He needs a place in Palm Springs and a “cottage” in Saskatchewan on the lake. It’s got to be huge, with a boathouse, a couple of Sea-Doos and a fishing boat, because God, he can’t fish out of the pontoon boat.

So what happens is, he’s focused on all those things instead of what made the money and made him. How can you concentrate on hockey when you’re worried about the lawsuit you’ve got going because the builder fucked up your five-million-dollar renovation? I mean, think about the people this 30-year-old guy is responsible for: a wife, his family, several employees, an agent and three little kids. He’s sleeping three hours a night if he’s lucky.

Veronica and I built a house on McKenzie Lake, a beautiful house, brand new. We designed the whole thing. But then an eightthousand-square-foot house on the lake came up for sale. We said, “Fuck, we gotta have it, right? We’ve just gotta have it!” So now we had two houses. Then I got traded two weeks later, and then I went to New York. Fuck! I needed another house—I had nowhere to live. Now I had three houses, plus a cabin in the Shuswap that was being gutted and redone, right? So with two little babies and a ten-year-old and four houses, it’s no wonder I wasn’t playing up to expectations. The Flames were actually a little better on the road than at home this past season. Why? Because they didn’t walk through the door and have to think about fuckin’ cedar shingles.

NHL players’ wives are mostly small-town girls. It’s hard to go from shopping at Sears to shopping at Holt Renfrew without getting caught up in it all. It becomes part of their lives. If they’re not shopping, they’re not doing anything.

In 2009, an ESPN reporter asked Alex Ovechkin how he managed to get a Mercedes SL65 AMG Black Series when there were only a few hundred in the world. He replied, “Because I’m Ovie.” These guys think they are invincible. I know I did. Until it all falls apart. In 2003, the year after he won the Calder Trophy, Dany Heatley drove his Ferrari into a brick fence, killing teammate Dan Snyder. That could easily have been me or a hundred other guys. It’s not their fault that they lose perspective. Seriously, if someone handed you a cheque for $400,000 every two weeks, what would you do—stay home and make popcorn?

What young players don’t realize is that, as much as everybody is telling you everything is going to be okay, and you’re going to be loved and admired and all that shit, once the paycheques stop coming in, you’ve built this empire that costs a hundred thousand dollars a month to maintain. That means dipping into your savings. And most financial planners will “fee” you to death and put you in the mutual fund game, stuff like that. Guess what? When you take the money out, you’re re-taxed.

Summer practice with some of the boys before my comeback attempt.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

Training with Jill Sagan and Cory Fagan at TCR Sports Lab in Calgary.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

It felt good to be wearing a Flames jersey again.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

Joking with reporters at the press conference for my retirement. It was tough to walk away from the game.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

With Jenn at my side when I announced my retirement.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

It was a tough decision, but it was the right decision.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

With Larry Day after he put me through the grind, preparing me for the media explosion.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

Kirstie and me at a book signing. I was shocked that people lined up for hours.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

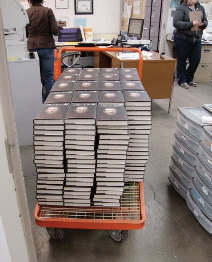

The stores couldn’t keep the book in stock!

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

Jamie Salé admiring what a great skater I am.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

Wearing the headdress I was given when I got my new name, Ihkinohpota, which means “light falling snow” in Blackfoot.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

With Jenn, seeing Graham James for the first time in fourteen years, on TV.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

In December 2009 I played a few games with the Oldtimers Hockey Challenge. Can you imagine playing with all these Hockey Hall of Famers, or guys who should be in the Hall, back in the day? These guys were awesome: Glenn Anderson, Bryan Trottier, Bernie Nicholls, Dale Hawerchuk, Billy Smith, Tiger Williams. That’s Probie, lying across the front. We had some great talks on the road. It was good to see he was working to get his life together. He talked about his family a lot. They were his world.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

When I toured with the Oldtimers Hockey Challenge, I got to team up for a song with Bryan Trottier and Michael Burgess.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

Who knew I would find a whole new career in public speaking? It’s also a good step in the healing process.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

Everybody thinks that $50 million is some ungodly amount of money. It’s not. After the taxman gets his, well, that’s $25 million. You get married a couple of times and divorced, that’s half again, so now you’re down to $12.5 million. Then the bottom falls out of the market and all that money that you spent building your portfolio? Forty per cent of it disappears, up in smoke. So you turn to the NHL pension fund, but it’s dropped about $100 million thanks to the recession.

I played in the United States for four years, and what’s the total value of my U.S. pension? Forty thousand dollars. What was my NHL pension in Canada worth in 2009? Two hundred thousand. For a fifteen-year career, that’s $240,000 in total.

Older players should be recruited to educate the younger players about the importance of taking care of their finances properly. It would make a big difference. Most of us veterans have to work, slug it out. Recently, I was on the road with NHL legends—true champions. Guys like Bryan Trottier, Glenn Anderson, Billy Smith and Dale Hawerchuk. A few of these guys are set for life, but others busted their nuts to make the game what it is today. Some are in good financial shape, some sign autographs and pictures just to pay the rent.

Old guys could also help with lessons about team. Pros work hard to get where they are, but they are a business within a business. When you have twenty separate businesses within businesses in the room, what do you lose? You lose the team part. You still have guys like Sidney Crosby and Ovechkin who have a few drops of old-school blood in them. They play the game for the right reasons and they know they can’t win by themselves, that they need Billy Guerin or Mike Knuble on the right wing, and a coach like Bruce Boudreau, who played most of his career in the minors.

I’m not saying that the entire hockey world is fucked. There are still great people around the game. But I don’t think there are enough of them. When we don’t remember where we came from and we try to become something else, we lose ourselves. For example, after spending so much time on reserves and speaking to the elders, I’ve found that the biggest fear is that the heart of the people will disappear because their children don’t speak the language or follow the traditions. In the NHL, Tyler Seguin has to know who Lanny McDonald was, just like I had to know who Ted Lindsay was, because Ted Lindsay did what he did so I could do what I did.

Look at Pittsburgh—they’ve got Mario. The Maple Leafs—okay, they’re not winning, and it’s a tough town to win in because of the media pressure, but when Doug Gilmour was there they had success. In the 1990s, they had some old-school guys with hard balls, like Jamie Macoun, Rick Wamsley, Wendel Clark and Glenn Anderson, guys like that, with Pat Burns as the coach.

In the end, if you forget where you came from, you lose. The game has lost its tremendous history of characters. Where are the Eddie Shacks, the Phil Espositos, the Bobby Clarkes and the Butch Gorings with the Velcro skates? Where are all those guys? We built the game. I don’t want people to think that I’m bitter. I’m just saying what thousands of sportswriters, fans and ex-players are thinking when the PR department from each team tries to brainwash us all with statements like, “Today’s game is faster and better.” For the most part, the game today is trap hockey in the regular season. Anyone watching the playoffs can see it is still a great game. This past season, with Montreal against Pittsburgh, San Jose and Detroit, Chicago and Vancouver—I loved those games.

The Flames are super fit, so what could help them make playoffs? Well, there are guys around who are so valuable—more than you can possibly imagine. I sat beside Jarome in the dressing room during my comeback. We talked a lot about the old days and how much fun we had. Lanny and Patter, Pep and the boys—we would enjoy each other’s company. We would actually discuss more interesting topics than what fuckin’ car the other guy was driving. We’d always be joking around, having fun. You know, waiting for Macoun and Nattress to have an argument. “Nat, I got a buck in my pocket.” “No, you got two dollars. I know you’ve got two fuckin’ dollars.” You know, get the testosterone churning, arguing just to argue.

What would I do if I were running the team today? I’d hire every single guy from the ‘89 Stanley Cup team. I’d phone them all up and I’d say, “All right, we’re having a meeting at the Saddledome. Give the secretary your flight information, we’ll all get together.” We wouldn’t have to develop a winning chemistry; we already have one. We trust each other, we know each other and we all have ties to the Flames organization. Timmy Hunter would be my head coach, because he’s been coaching for ten years as an assistant to Ron Wilson. Right now, Timmy is in Toronto, because wherever Ron Wilson has gone, Timmy has been his right-hand man. And Wamsley, who has been coaching since 1993 and is now head coach of the Peoria Rivermen in the American Hockey League, would be a good assistant coach. So would Dougie Gilmour. He’s coaching junior in Kingston. Roberts would be my strength and conditioning guy. Lanny would be GM. Pep would be the business guy. Nattress, Macoun, Mark Hunter and Brian McClellan would scout. Otts would be another assistant coach. As for Colin Patterson, there are lots of places for a smart guy like him.

It’ll never fuckin’ happen, of course. The Montreal Canadiens built tradition with their guys. Jean Béliveau, Yvan Cournoyer, Serge Savard, Henri Richard—whenever the Canadiens have a celebration they bring in all their guys. They are invited to every game, every function. They are forever a part of the team. Former players don’t have to call the PR guy and give him their credit card information for tickets. When I played my thousandth game, I was presented with my silver stick in New York by Mark Messier, Brian Leetch, Eric Lindros and Glen Sather. Iggy and Daymond Langkow each played their thousandth game on February 11, 2010. Did Lanny and Vernie, the only two guys with retired jerseys, hand sticks over to the boys? No.Team president Ken King did. I like King, he’s a good guy, but presenting a silver stick is not a job for a suit.

FOR THE FIRST TIME in six years, I was on the ice in an NHL-level game, when Dion Phaneuf comes off the bench, goes for Kyle Okposo and knocks him into last Tuesday. If you’re skating through the neutral zone with your head down, you deserve to get it knocked off your fucking shoulders. And that is what happened to Okposo. It’s the first thing they teach you when you start playing hockey: keep your head up. When Phaneuf’s on the ice, you know he’s going to try and decapitate you. So if you skate through the neutral zone looking all over the ice for fuckin’ Skittles, Dion will be licking his chops. Every time I faced Scott Stevens, don’t you think he was hoping that I would skate in with my head down? I do think Mike Richards’ hit on David Booth and Matt Cooke’s hit on Marc Savard were taking it a little too far. Those guys were blindsided. If it were back in the day, Richards and Cooke would have had to make emergency appointments with their dentists right after those games, because we used to do a great job of policing the game. Everybody who played was accountable.

When I made The Show, I didn’t like to fight, but I knew I had to because I was always running around spearing guys. About three times a year I would have to drop my gloves and pay the piper. But the instigator rule takes that accountability out of the game. So if Cooke hits Savard, and somebody on Savard’s team goes after Cooke and beats the shit out of him, Savard’s team gets an extra two minutes for instigating a fight. And it’s getting worse. There are three more calls implemented to pink up the game every year. And that’s why fans can’t feel part of it. They aren’t as invested without the one-on-one rivalries. You don’t get Joel Otto and Mark Messier in a demolition derby. You don’t get Theo Fleury and Esa Tikkanen jabbing each other and riling up the crowd.

Another reason you cannot play one on one anymore is because of coaching. Coaches need to go back to making two hundred thousand dollars a year. Make it a flat rate. Every coach gets that—they don’t move up, they don’t move down. When a million-dollar coach looks at his team and says, “I have no fuckin’ chance in hell of winning,” he coaches in a way where he’s not going to give the other team anything. That way, he might squeak by 1–0 and keep his job. But the fans fall asleep.

There used to be only one coach behind the bench. Now you can find seven coaches. Look at old Scotty Bowman in Montreal. It was just him. That was it—he was running the whole bench. The Flames have so many guys that their play is completely overanalyzed. During practice in 2009 after an exhibition against Vancouver, Rob Cookson, who’s the video guy, was on the ice. I don’t know what the fuck he was doing on the ice, but he came up to me and said, “Your line wasn’t very good in Vancouver.” I was like, “Fuck, now I got the video guy telling me what to do.”

When Okposo was lying on the ice, we got into a scrum. I was grabbed by a kid named Greg Mauldin, a former Hobey Baker nominee from UMass, and he was excited. “Hey man, you’re my hero. I always wore 14!” I just started laughing. But another kid, a short-ass meathead, started lipping me off from the bench. I was like, “What are you doing?” He looked at me and said, “Who the fuck are you?” And I was like, “You’re joking, right? I can send you a videotape of all my highlights if you want.”

EVERY PRACTICE, EVERY GAME, I was surrounded by the media. And the team loved it. Craig Conroy and Jay Bouwmeester told me they appreciated how it took the pressure off them. In the four games I played, I averaged about twelve minutes of ice time. Didn’t get power-play time, didn’t kill penalties and wasn’t out there in the last minute of the periods. But I kept going about my business. I wasn’t the Theo Fleury who left the game in 1998. I was just a guy trying to make the team.

In my mind, I had already made it. I was making plans to play the whole year. I was integrating myself into the dressing room, trying to figure out where I belonged. What did they need? They had changed coaches every two years and they were still not getting it done. So how could I come in and make an impact? I figured I would laugh, joke around, keep guys loose. Tell them stories about the old days, and they’d look at me going, “What the fuck? You guys did that?” Start working with the underachievers. Convince these guys that they are better than they are, give them pointers. I would ask the fourth-liners why they’re on the fourth line, and they would say, “Oh, I don’t know, because I’m a young guy.”

I would say, “Well, that’s a lame excuse. How about you try beating the guy who’s playing on the third line?” But the first thing I would do was talk about winning, because that was a word nobody was using.

Peplinski came to practice, encouraging me. He said, “You’re looking good.” Claude Lemieux was so supportive. He actually called Darryl during camp and told him he knew I was sober and working hard. The guys on the team were great, respectful. They’d give me a nod or a word.

I was playing a little frustrated. The game is very controlled. When the Flames lost out to Chicago in 2009 and they fired Keenan, Darryl said the Flames were a hard group to coach. He said they needed more structure, more discipline. So I already knew I couldn’t use my instincts and feel my way. To make the team, I had to learn the system. The system needs positional play, so I was making mistakes. Say one of my linemates—Curtis Glencross—would have the puck, my instinct would send me one way, but I’d have to pull the emergency brake and move up or back to where I was expected to be.

I made a couple of decent plays. In that first game, I got a hooking call in the third against Islanders defenceman Mark Streit. I blew on him and he fell over. They scored on the power play.

In that first pre-season game against the Islanders, the third period ended and it was 4–4. We went to a shootout. Brent Sutter leaned down and said, “You’re up second.” My hair stood up in my helmet. I couldn’t believe what was going on. Nine months before, I was a fuckin’ whale, I hadn’t worked out in six years. How does that compute? I think it was serious divine intervention that brought me to that moment, a moment of redemption.

Matt Moulson went up first for the Islanders and did some junior bullshit move and failed. Nigel Dawes shot first for us and missed. Trevor Smith took off from the middle, and he missed. So now the stage was set.

I had to score to give my story a happy ending. I just had to score. Whenever I have no choice, a calmness comes over me. I turned on the autopilot. The crowd was going fucking ballistic; I shut out the sound. I started gliding back and forth along the blue line, looking at Kevin Poulin, the goalie, a rookie. I’d never seen him play. What was his weakness? Five-hole? Blocker? Who the fuck knew? The ref dropped the puck. I was back in Russell, playing shinny—not thinking, just reacting. Who was going to crack, me or him? I don’t like to deke, so ten steps from the circle, I opened my legs to shoot. Fuck, he had it covered. I had to improvise in a split second. I faked him and he spread out. I had him if I could manage to control the puck, because he was committed. I took it across to my forehand and bam! I beat him so bad he had to help the goal judge flick the light on.

The crowd went fuckin’ crazy. I moved up and down our bench slapping leather. The boys were really happy for me. Oli, Jarome and Conroy were all wearing big shit-eating grins. But the Islanders were not dead yet. Greg Moore was up. He faked a shot, deked on his backhand and … missed. I was first to our net and wrapped myself around our goalie, David Shantz. Robyn Regehr, Moss, Iggy, Phaneuf, Mark Giordano—all the guys came in on us. I was happy, just so fuckin’ happy. I came out from the middle clapping for the fans, blowing kisses. They believed. They were chanting my name, “Theo! Theo! Theo!!” A standing O. I soaked up every second. It was a new chance on life.

One of the reporters asked me about my feelings regarding the overtime goal. I said, “I don’t miss those chances ever. Not in the big moments. Never have, never will.”

Back on the road, one of the biggest surprises for me was that I was cheered in the two cities where I had been hated the most, Vancouver and Edmonton. It was awesome. The fans had class. After Edmonton, we went back to Calgary for a couple of days off and then the last exhibition game was scheduled against Vancouver. We all knew there were some cuts coming down.

The first four lines switch up red, white, gold and black jerseys. The fifth line wears blue. When I walked in a couple of days before that final game and there was a blue jersey in my stall, I knew it was just a matter of time.

I went into the training room. My groin was sore, so I was heating it up, getting ready to go on the ice, when Morris Boyer, the trainer, came up to me. “Darryl wants to see you.” I went into the coach’s office.

Darryl said, “I’m releasing you.”

I buried my feelings and shrugged, “Okay, cool.”

Then he said, “Ken King wants to talk to you,” and he walked out.

I was hurt, trying to breathe it out. But my eyes kept heating up. I had to leave. I had to get out of there. Ken came in and said, “How are you feeling?”

I looked at him. “How the fuck do you think I’m feeling? It hurts, man. It fucking hurts.”

He nodded. “Well, what are you going to do next?”

I said, “I’m going to go home, I’m going to talk to Jenn and the kids and then I’ll decide.” I quickly got dressed and I left. They didn’t want me there? Fuck it, I was gone.

I jumped in my truck, and as I pulled out of the Saddledome, I started to feel better. I was done. It was good enough for me. I gave it my best shot. Now it was time to retire.

I called Jenn and told her I had been released. She was pissed off. She saw how hard I’d worked and how dedicated I was to making it a reality when nobody thought I could do it. She was pissed that they ignored my wins at the World Juniors, the Turner Cup, the Stanley Cup, the ‘91 Canada Cup, the 2002 Olympic Gold and the win in Belfast. She said, “You’ve got six fucking rings in the closet. They don’t think you can take it to another level? Like, seriously, come on.” I told her to settle down, I was okay with it. I had accomplished what I wanted to accomplish.

I called Baizley and he agreed. He was happy for me. “What more can you prove? You’ve done a great job.”

Beaux and Tay were scared. They said, “No! You can’t go to another team. We don’t want to get on a plane to come visit you.” I told them I wasn’t going anywhere. I called Josh, he was really upset.

Ultimately, I chose to keep my family happy. When Jenn was growing up, she went to eight different elementary schools and four different high schools. I didn’t want that for Skylah. Josh, Beaux and Tay needed me to be around, too. In the end, it was a family decision to leave hockey. I would remain a Flame forever.

Iggy has said he has never played with a more intense guy than me. He called and left a message. He just wanted to say goodbye. “I understand that you were pretty upset. You left so quick, I didn’t get a chance to talk to you.” He gave me his number and said, “Call me if you want to talk.” It is hard to break the bonds of war.

The next day, Friday, I called the Flames and asked for a press conference on the Monday. Jenn and I sat down and wrote a speech. I had to be careful, because the competitive side of me was really pissed off, so I told my diplomatic side to step up.

The whole media room at the Saddledome was full. People were lined up against the walls. In my speech, I gave most of the credit for why the Calgary Flames are the Calgary Flames to Harley Hotchkiss, Doc Seaman and B.J. Seaman. I remembered a line from Doc’s funeral: “Leave it better than you found it.” I said I thought I’d accomplished that. I thanked Jennifer for allowing me to be a part of her life because none of this would have been possible without her. And I thanked my fans, letting them know I wasn’t going to sign with another team and would get to retire as a Calgary Flame. I ended with, “Don’t quit before the miracle. Thank you for your time today.”

WHY DID I WRITE this book? Do you want me to be honest? I wrote the book because I was fuckin’ broke. Flat broke. There was nothing going on. Our concrete business was failing badly, and Jenn was freaking out, wondering what the rest of our life was going to be like.

In 2006, I was at a Flames golf tournament when I ran into Larry Day, a media guy I knew. He asked what I was up to. I said, “Fuck all. I got nothing going on.” He mentioned that his wife, Kirstie, was a writer, and maybe we should meet. I didn’t want any of the usual sportswriters writing a book about me, for two reasons: I had trust issues with guys, and it would be tough to tell another guy about all the private facts. So we met, and it sounded like a good idea, because I didn’t want people to see me as a broken guy anymore.

After the first couple of sessions with Kirstie, I was still asking myself, “Is this the right thing? Should I really lay it all out for her?” By our third time together I did—pushed up from the bottom of the pool, hit the surface and sucked in air.

I was angry and resentful in the early months, fuckin’ right I was. But through the process, I was able to leave all of that behind me and become this incredibly empowered person. Especially when I began to realize that I could help people come to grips with their own nightmares.

When the book came out, I knew it would be a fucking gong show, but I really had no idea how out of control everything would get. Everybody involved with the book was paranoid that the contents would get out there early.

CBC’s the fifth estate was scheduled to come interview me before publication. I had never talked about what happened with Graham James to the press, so I practised with Larry Day. He brought the Flames This Week crew from Pyramid Productions over for a dry run, and we sat down with the lights and cameras. He came at me. Hard. Think of coming up the middle with the puck, and fucking Scott Stevens is headed your way, ready to destroy you. It was the best thing that could’ve happened, because I faced a steep learning curve.

The whole thing blew up in the media when, during the production of the fifth estate piece, they tipped the abuse story to the Calgary Sun. The Sun ran an article that was picked up everywhere, and the phone started ringing. I got the hell out of Calgary with Jenn and Skylah. Everybody wanted details. What happens when someone makes an accusation about abuse? Let me give you an example. Recently in Calgary, a 15-year-old girl made an accusation against a coach, and instead of camping on the coach’s lawn, reporters were on her doorstep. I didn’t want that to happen at our house. Jenn’s brother Brad lives in Ontario, and his house is in the middle of some tobacco fields in butt-fuck nowhere, so we decided to go there.

Meanwhile, I got an email from an organization called 1 in 6, which helps survivors, mainly through their website. I thought it couldn’t be more perfect, and that I could do some good. It gave me strength. My mission was not to make Graham James more famous than he was. It was not about what happened in that dark room and all the shit that went on in there. I wanted to let people know that Theo Fleury, a famous sports star, had been abused, and I was only talking about it so that other victims could see that you can get through it. The only reason I put as much stuff in here as I did about alcohol and drug abuse was because I wanted the normies to understand why abuse takes you to the places it takes you.

I went on the book tour and was asked three questions: “What was the extent of abuse?” “Why did you let Graham get involved with the Hitmen?” and “Tell me about your crazy behaviour.” In my head, I was saying, “Fuck off, fuck off and fuck off.” I mean, psychologists and psychiatrists can’t even really explain it.

I have some good friends who are respectful, honest reporters. George Stroumboulopoulos, host of The Hour, is one of my favourites of all time. TSN’s Darren Dreger, who is from Langenburg, Saskatchewan, only twenty miles from Russell, is a good guy. And Michael Landsberg of TSN’s Off the Record was really sympathetic and respectful as well as being a fuckin’ riot. There were other good reporters too, but others tried to make me crack. I think some were waiting for me to go off the deep end, to become completely fucking unglued. And why not? It would be consistent with my past behaviour. But that would defeat the purpose of writing the book. If I went on camera and someone threw a question at me and I snapped, that poor bastard at home would be saying, “There’s no fucking way I’m going to tell anybody now.”

What was really interesting was that I felt I could tell who had also been abused. One radio host seemed really uncomfortable. He didn’t bring it up, but it was as if the ghost of his molester was sitting on the table between us. When his co-host suggested I stay for another segment, I thought the guy was going to pass out.

A surprising thing happened at the first book signing in Toronto at the Eaton Centre. At least four hundred people showed up. They came up to me and said things like, “Holy Cow! I read the book in three hours, couldn’t put it down.” Or they had seen me on the fifth estate or The Hour or Q, or on TSN or Sportsnet or Flames This Week. Ten minutes after I had begun signing, this older gentleman with a fifty-dollar haircut and a good suit came up and leaned over to me, and quietly said, “Me too.” I looked up at him and we both choked up.

Some guys couldn’t even get it out; they just stood there. I’d say something like, “Do you need a hug, man?” I met about fifteen thousand people, from all walks of life, on the book tour, but the guys who shared their secret with me were usually in the grey-at-the-temples age range. I felt for them all. I knew the long, lonely highway they were stepping onto. Each was right at the very beginning of his trip to Feel-Better. It took me eight years of therapy before I felt I could move on.

One elderly gentleman who looked like Santa Claus said, “I am 67 and it happened when I was 12.” I gave him a hug. “You are not alone, man,” I told him. He broke down. This poor guy had to go through the horror for fifty-five years—twenty thousand days—with no outlet. That hit me hard.

Statistically, about one-sixth of the male population has been sexually abused as children. What does that tell you? It tells me that abuse is acceptable in our society. It is too embarrassing for us to deal with. I look at it like this: What if a guy went around cutting off kids’ thumbs? Would that be okay? No. He would be arrested immediately. So why do so many child molesters get away with cutting off children’s innocence?

When we started up my website, theofleury14.com, one of the first emails I got was from a lady in Saskatchewan. “I get too emotional when I read your book alone, so I’m reading this book with my therapist,” she wrote. I was getting about twenty emails a day. Out of those twenty, at least three were stories from survivors. I replied to them all, usually referring them to the 1 in 6 website or the Mens’ Project in Ottawa. Their websites blew up when the book came out.

A lot of the emails made me swallow hard. One story really got to me. The guy said he tried to write me four times before he was finally able to. He called himself a professional alcoholic, drug user and gambler. He said he took extreme risks in snowboarding and skiing, dirt biking and BMX freestyling, and he had found a profession that fit him like a glove: as a connector on an ironworker gang building skyscrapers, arenas and hospitals. He said he sat at the end of a steel beam connected to a crane, flying through the air at five hundred feet, with a bolt bag on each side—one filled with bolts, the other filled with beer. Even though he was married with three kids, he partied hard, usually ending up in strip clubs and dingy motel rooms with prostitutes. Life caught up to him early one morning when he got into an accident and heard his neck break. He said that when he couldn’t move his legs, it hit him. “Fuck me, I’m paralyzed.” After two years of intense rehabilitation, his wife left. But he said he was a stubborn son of a bitch, and even though he was a quadriplegic he appreciated that he was alive and would get to see his son grow up. He said that when he read the line from my book, “You are only as sick as your secrets,” it struck a chord. His secret was that he had been molested by his sister from the time he was eight until he was eleven. He said he had never heard anybody talk about being molested before, and that the book helped him turn the corner.

Some of the media guys started getting down on me for not complaining about the abuse to the police. Holy shit. I could understand pointing fingers at me for being a drunken asshole, or for not being there for my kids. But I was shocked at being judged for not being ready to go to the police. It was one thing to put it in the book, but the idea of spelling out all the details in person, in front of my wife and kids and parents and friends, was not something I looked forward to. What they failed to understand was that I didn’t have any power. I wasn’t the one who decided whether to press charges against Graham. That was up to the police. I wish I had that much power.

My dad called me, all busted up. “This has been hard, reading the book,” he said. “I’ve had some tough days.”

I said, “Dad, you know what? Are we still at the point in our lives where we give a shit about what people think about us? People have a lot of shit they haven’t dealt with, and because ours is public, they can forget their own. They can say, ‘Well, at least I am not as bad as the Fleurys.’ Fuck, man, look at how far we have come as a family! People don’t go through what we have gone through and still talk to each other. We might be all messed up, but we are strong. We are together.”

I made it to Winnipeg, where a lot of the abuse took place. I spoke with Detective Ken Ehmann and Sergeant Douglas Bailey of the Winnipeg Police in a little room with a camera. At first, I hadn’t wanted to go to the police because I didn’t need an outcome, I didn’t need justice. Through my process, I am now at peace. But I also realized I had a responsibility to others, especially innocent kids.

I say in the last part of the book that I want to help, right? Well, if I didn’t go all the way, I’d be full of shit, right? I was talking the talk, so I had to walk the walk. It was a tough walk that last four or five hours.

I hesitated, though. A few things I found out on the book tour kind of put me off. I heard a lot of horrifying stories from people who had gone to the police and been revictimized. They were a mess. So I was thinking, “What if we don’t get justice? How am I going to handle that?” But then I thought, “I’m a high-profile guy, the law will have to act on my complaint or there’s going to be a problem.” I was convinced everything was cool. I felt nothing. I was over it. I told my story to the detectives, got back to my hotel that night and started pacing the room, feeling pissed off.

When I get that way, I need something to do. I could see the Flames weren’t going to make the playoffs, and I knew in my heart I could have made a difference. I am a Flame; I always will be. I love the team, I care about the team. I said to myself, “Fuck, I pay for my ticket like everyone else, I am entitled to an opinion.” I hadn’t put any blogs up on my website for a long time, so I vented. I said that in four preseason games I was a plus-four with four points and that I finished eleventh in fitness out of fifty-six guys after being on the couch for six years, yet I still got cut. I questioned the fairness of keeping Conroy instead of me, because he had no goals in the first thirty-seven games, and I said Iggy needed someone to pass to. I was hard on Regehr. It was stupid. Neither Conroy nor Regehr deserved that. It made me sound ungrateful for the chance the Flames had given me. I was an asshole. I should have kept my feelings to myself and I apologized publicly.

IN APRIL 2010, I was alone at home when I heard that Graham James had been pardoned for molesting Sheldon Kennedy. What the fuck? What did that mean? I went online and found out a pardon does not erase a person’s criminal record, but it ensures the convictions are kept out of a police database used by officers throughout Canada. It basically meant he didn’t have a record anymore, so he could hang around boys again.

The old Theo would have been calling everybody, just fuckin’ losing it. Instead, I called the Men’s Project, which is based in Ottawa, and I said, “Let’s do something to stop these sick fucks from being able to travel the world finding new prey.” I spoke up on TSN. “We think of Canada as a safe place for kids, but it is not.” I told the Calgary Herald that the National Parole Board officials had dropped the ball.

When Prime Minister Stephen Harper sent out a statement saying the pardon was “gravely disturbing,” I contacted his office and said I wanted to help make a difference. But, obviously, I couldn’t do anything official until after my complaint against Graham went through the legal system.

I started up a not-for-profit organization called the Theo Fleury Society for Abused Men to help survivors find help. Our mission statement is “To create public awareness and fund programs that enable male sexual abuse survivors to have a voice, get professional support and become fully functioning, empowered members of society.” Right now, a lot of victims just don’t know where to go.

I GET HUNDREDS of emails every week, and many are from First Nations people. They have inspired me to connect with my roots. A lady named Grandma Ruth Shield Woman, who is from Siksika Nation, a reserve near Calgary, asked me to come and hang out with the kids as a role model. She gave me a kit with some herbs, including sage and sweetgrass, and taught me smudging, to get rid of negative spirits. She told me to bury the ashes in the four corners of my yard every morning for protection. And sure enough, after I started doing that, three eagles began to fly over my house. The Great Spirit was there. Shortly after, I went to a naming ceremony in my honour and got my first Indian name: Ihkinohpota, pronounced ikky-knock-poota. It means “light falling snow” in Blackfoot.

I did my first sweat with Grandma Ruth’s husband, Grampa Francis Melting Tallow, and the Blackfoot people. Sweats have been passed down from the Grandfathers as a way of healing. Holy people who have been gifted run the sweat. Basically, you start a big wood fire outside and heat rocks. The rocks are brought into a hut that’s framed in willow branches with a hole in the floor. There is a big tub full of water and herbal medicine that they pour over the rocks. It’s about 140 degrees in there, and you pray and talk together for hours. You feel absolutely amazing when you get out because you leave your bad energy behind. It’s a spiritual steam room.

I started spending my days on the speaking circuit, and I developed a routine. Before I get up to the microphone, I pray. I invite the Great Spirit and the grandfathers into the room to use me as a vehicle to speak, and it just happens. After I finish, man, I’m fuckin’ spent. I’m tired. Emotionally, I don’t have anything left. I leave a little piece of myself each time. I want everyone I talk to to have hope.

I try to inspire. Speaking to Native students is one of my favourite things to do. First, I share some of my hockey stories, then I give them my tales of near-death situations and recovery centres. Finally, I ask young people to think about where they are at in their lives and to keep their options open. Drugs and alcohol slam shut the doors of opportunity and put the padlock on them.

I had just finished speaking at St. Clair College, as part of the Impact speaker series in Windsor, Ontario, and was about to board a plane when I got to a call from the fifth estate’s Bob McKeown. He told me they had found Graham James in Guadalajara, Mexico.

On May 12, 2010, Jenn and I sat down with some friends to watch the show. I hadn’t seen Graham in fourteen years. I was anxious. He was once a pretty powerful person in my life. How was I going to react? He came on the screen and I saw an old man who looked pretty powerless. He was way thinner. His double chin was gone, and he looked frail and grey. He was wearing a red-checked shirt and a beige ball cap pulled low. When Bob called out to him on the street, he kept walking until Bob mentioned me and Sheldon. Then Graham stopped in his tracks. It was pathetic—he was pathetic. But seeing him didn’t affect me like it did before. I knew I was going to sleep that night without those horrific images in my mind. And I did. I laid my head on the pillow, dozed right off and woke up refreshed and ready to go.

As it stands, the police are still investigating Graham. A few more guys have stepped forward since I filed a complaint.

Three years ago, I wondered why I was put on earth. Today, I know why. One day, when I was reading the AA Big Book, I landed on step three again: “I made a decision to turn my will and life over to the care of God as I understand him.” It hit me in the head like a fucking sledgehammer. Every time I was driving the bus, the bus always crashed. So I moved over to the passenger seat. Now I have my family back, and I am not broke because I am helping other people. My life is amazing, and it seems that opportunities are put in front of me on a daily basis. In the end, being of service to another human being is the greatest thing for somebody who is struggling. The biggest thing for survivors to understand is, “You were just a kid. It was not your fault!” I say it over and over again. It works like lifting weights—repetition makes the muscles stronger.

Now, if I have inspired you in any way, it is your turn. Go inspire somebody else, and remember, don’t quit before the miracle.