Mira Nakashima

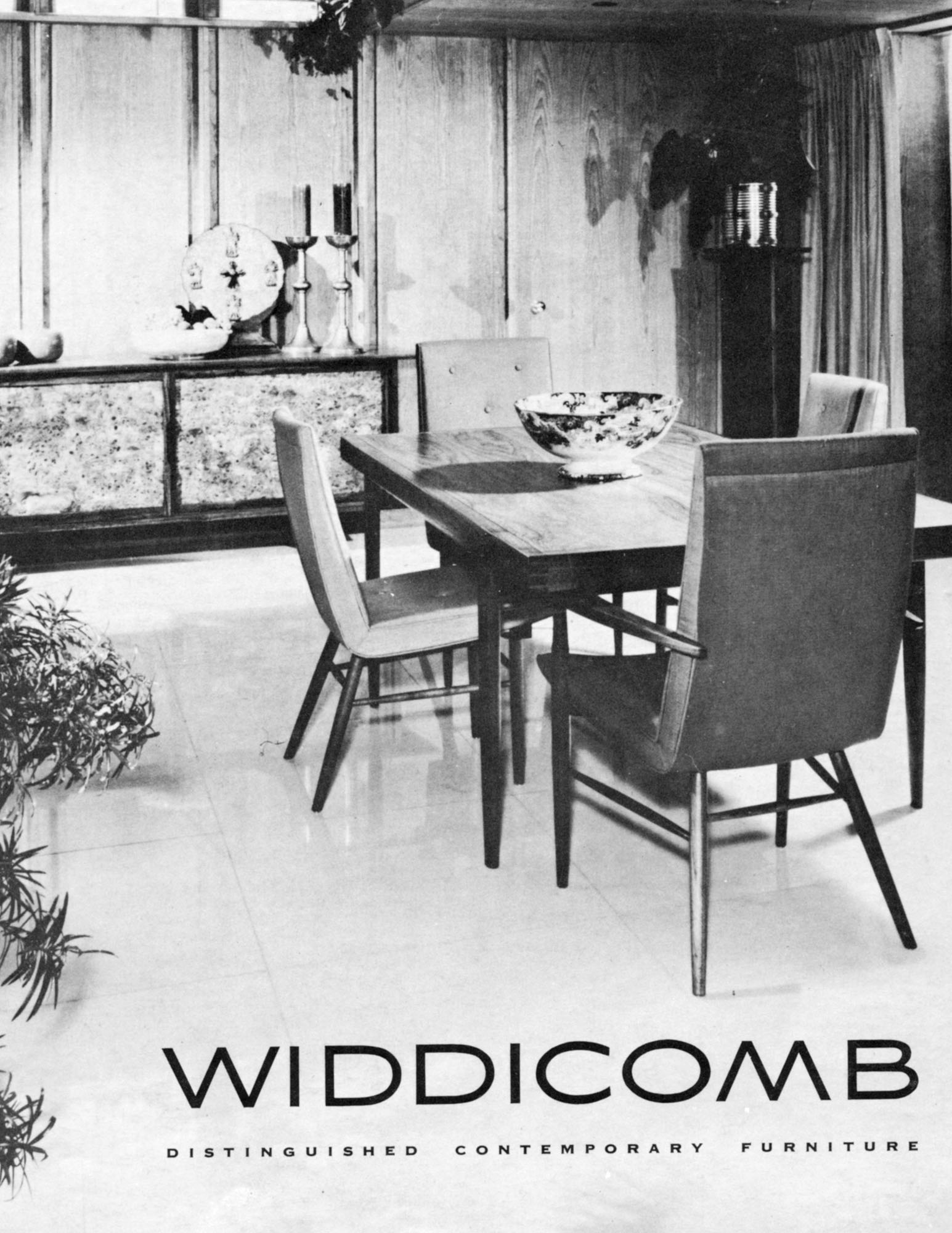

In the postwar era, Michigan architects and designers were more aligned with the organic forms inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright than with the steel-and-glass International style associated with Mies van der Rohe. Wood and stone warmed building exteriors while vivid colors defined interiors—the antithesis of Mies’s black-and-white palette. The work of George Nakashima for the Widdicomb Furniture Company of Grand Rapids[1] exemplifies the intertwining of natural forms with Modern design. The June 1958 catalog for the Grand Rapids Furniture Market had this to say about Nakashima’s Origins line, his venture into mass production for Widdicomb: “‘Different’ is the word for Widdicomb at this market. The company’s latest presentation in the field of original designs introduces an entirely new Mood in modern—achieved by means of highly individualized forms, fine woods, and many complete innovations in superb craftsmanship. . . . Every line of each piece is in harmony with the natural flow of the wood grain. . . . Because entirely new forms characterize the Nakashima collection, production of these pieces has required specially developed manufacturing techniques never before attempted.”[2]

Modern design in Michigan, from architecture to furniture, was often fueled by the desire to solve a problem rather than perpetuate a specific style. Michigan’s designers were looking for new solutions to the challenges presented by a unique site, a new material, or an untried method of manufacturing. Their distinctive solutions often made it difficult for critics to define their work. The designers working with Michigan’s manufacturers wanted to change the image of mass production and show that a quality product was possible. As Nakashima stated in the 1958 Grand Rapids Furniture Market brochure: “But periods of design mean nothing. There are just two kinds of furniture. Good—and bad. If it augments life through the grace and appreciation for beauty which it engenders, it is good furniture, whether period or modern. If it is slicked-up folk art, or one of the decadent industrialized designs made to show off the tricks which machines can perform, it contributes nothing to the enrichment of daily living—and it is bad furniture.”[3]

By honoring the aesthetics of the talented designers they hired, Michigan’s furniture companies produced Modern furniture icons that endure to this day and define our image of American Modernism.

Widdicomb Furniture catalog showing a dining set from Nakashima’s Origins line, c. 1950. Courtesy Grand Rapids History & Special Collections, Archives, Grand Rapids Public Library.

George Nakashima was born in 1905 in Spokane, Washington, to Suzu and Katsuharu Nakashima. The oldest of four children, he grew up in the Pacific Northwest, was an Eagle Scout, and attended the University of Washington, studying forestry for two years before switching to architecture and graduating in 1929. He received a scholarship to the Fontainebleau École des Beaux-Arts, as well as to Harvard University, but switched to MIT and received his master’s in architecture there in 1930. Employed as a landscape architect by the New York State Park Commission during the Great Depression, he eventually returned to Paris and then Tokyo, Japan, in 1934, where he became an employee of the Wright-trained Czech architect Antonin Raymond. As part of that office, Nakashima was responsible for not just the exterior architecture, but also their interiors, and was sent to India in 1936 to work on the first reinforced concrete building constructed there. In Pondicherry, he became one of the first disciples of Sri Aurobindo and received the name “Sundarananda” (meaning “he who delights in beauty”) in 1938, but returned to the United States via Japan in 1940. He married my mother, Marion, in 1941, started his furniture business in Seattle, and learned a great deal by working alongside a Japanese carpenter while incarcerated in a Japanese American internment camp in the Idaho desert in 1942. At the invitation of Antonin Raymond, who had moved to Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in 1939, the three of us moved to New Hope in 1943, where my father began building furniture in earnest.

George Nakashima in his first workshop in New Hope, Pennsylvania, 1945. Photographer: Gretchen Van Tassel for the War Relocation Authority. Courtesy Mira Nakashima.

Although Nakashima sold some studio-made furniture through a gallery in New York City, he developed a line for Knoll that the company manufactured from about 1946 to 1954, maintaining the rights to make similar designs by hand in New Hope. My father had met Hans and Florence “Shu” Knoll through Antonin Raymond while we were living at the Raymond farm. He made most of Knoll’s marketed Straight Chairs in his own shop, until he signed a contract with Knoll in 1949 to mass-produce them and several other designs. My father’s philosophy of craft and design was nearly identical to that of Soetsu Yanagi, the founder of the Mingei movement in Japan during the 1920s, and very similar to the Arts and Crafts movement in Europe and the United States as well. However, making things entirely by hand made it nearly impossible to earn a living wage, so like Yanagi’s son Sori, he must have known that the only way to make good design available to more people was to have it mass-produced. It was also a question of economic necessity; we have learned from my mother’s meticulous record-keeping that my father earned more from Knoll than he did from all other sources at the time.

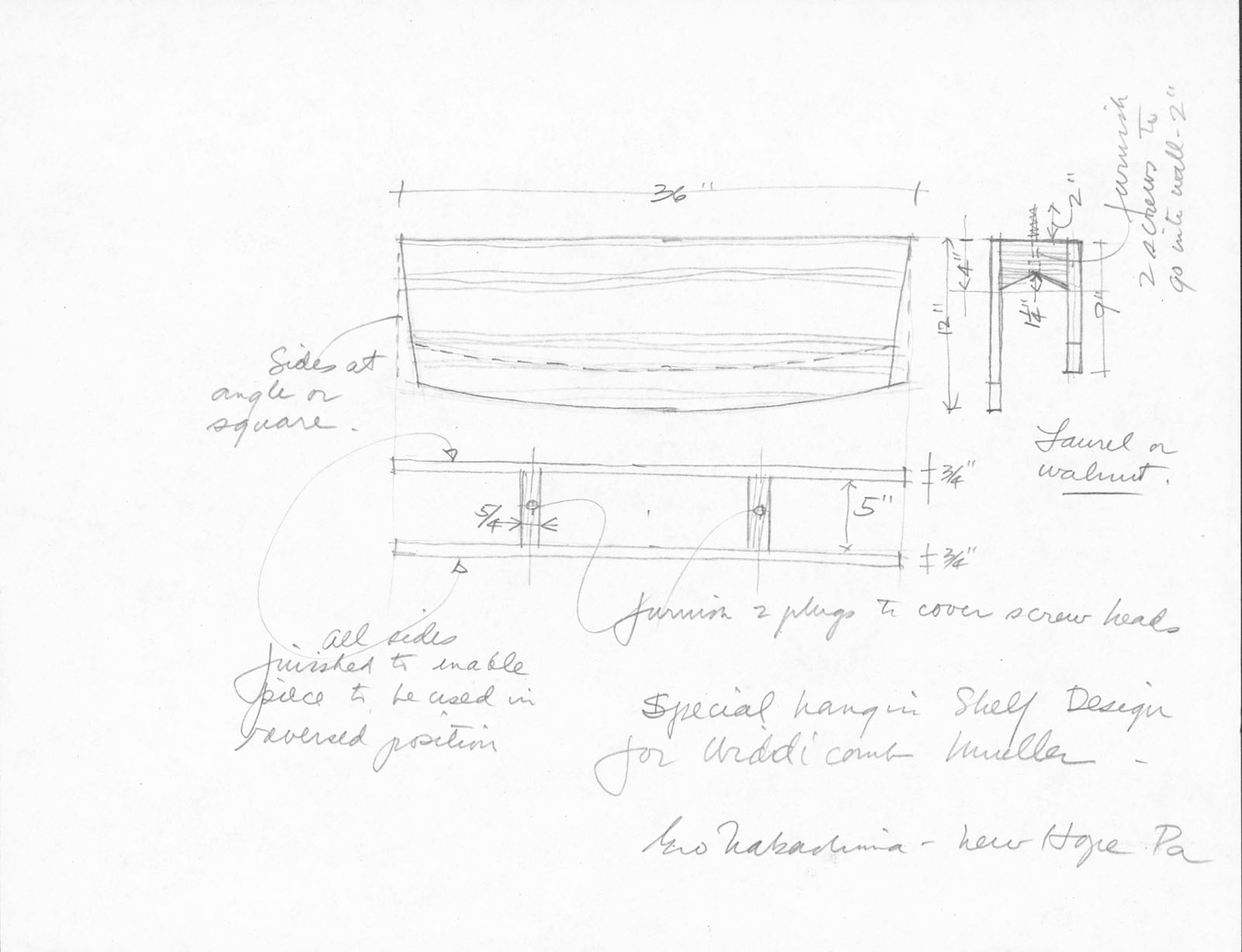

The perennial problem is maintaining the quality of materials, so Nakashima always reverted to making things in his own shop, where he could assure integrity of design as well as materials and craftsmanship. Although in the 1960s, he used a subcontractor in Plumsteadville, Pennsylvania, he was never quite happy with the quality of the product, even though it increased his quantity capabilities. In 1958, after the Widdicomb Furniture Company first contracted my father to design a new line for them, there is a fifteen thousand dollar payment recorded, with monthly royalties thereafter, which probably allowed him to build his highly experimental Conoid Studio with its reinforced concrete shell roof. After his relationship with Widdicomb ended in 1962, he never again worked in mass-production except to turn legs or spindles for chairs. However, we have recently renewed that old relationship with Knoll Associates, which now produces another version of the old Straight Chair, less expensive but noticeably different from my father’s studio-made chairs. All the royalties for these new chairs go to the Nakashima Foundation for Peace.

Nakashima laying out lumber for cutting at Sakura Seisakusho, Takamatsu, Japan, c. 1968. Photographer: Shinichi Nagami. Courtesy Mira Nakashima.

George Nakashima drawing of plans for a shelf for the Widdicomb Furniture Company, c. 1958. Courtesy Mira Nakashima.

The Widdicomb Origins line was by far the most consciously designed line that Nakashima ever produced. It represents his first and most extensive experimentation with long curves, both vertically and horizontally, using imported exotic wood veneers such as Carpathian elm burl, East Indian laurel, and rosewood, in addition to domestic woods such as black walnut and hickory. A new “Sundra” (meaning “beautiful”) finish was developed for the East Indian laurel, plus the standard Widdicomb finishes of fawn, sorrel, sherry or oil, walnut, umber, and satin teak. According to the 1958 Widdicomb Furniture catalog:

The Origins Group is the most recent addition to the Widdicomb Collection. Created by George Nakashima, who is one of the world’s greatest craftsmen in wood, Origins has been called “one of the most stimulating and thoughtful concepts of furniture design ever to be presented” . . . Most apparent are the unique shapes of sturdy stretchers, the way they are “shot” through the legs and pegged at both sides. There is a subtle elimination of straight lines; almost all pieces have edges that are beveled back ten degrees, many tops overhang substantially more than is usual; and upholstered pieces achieve a “forward thrust” due to the canting of the legs.[4]

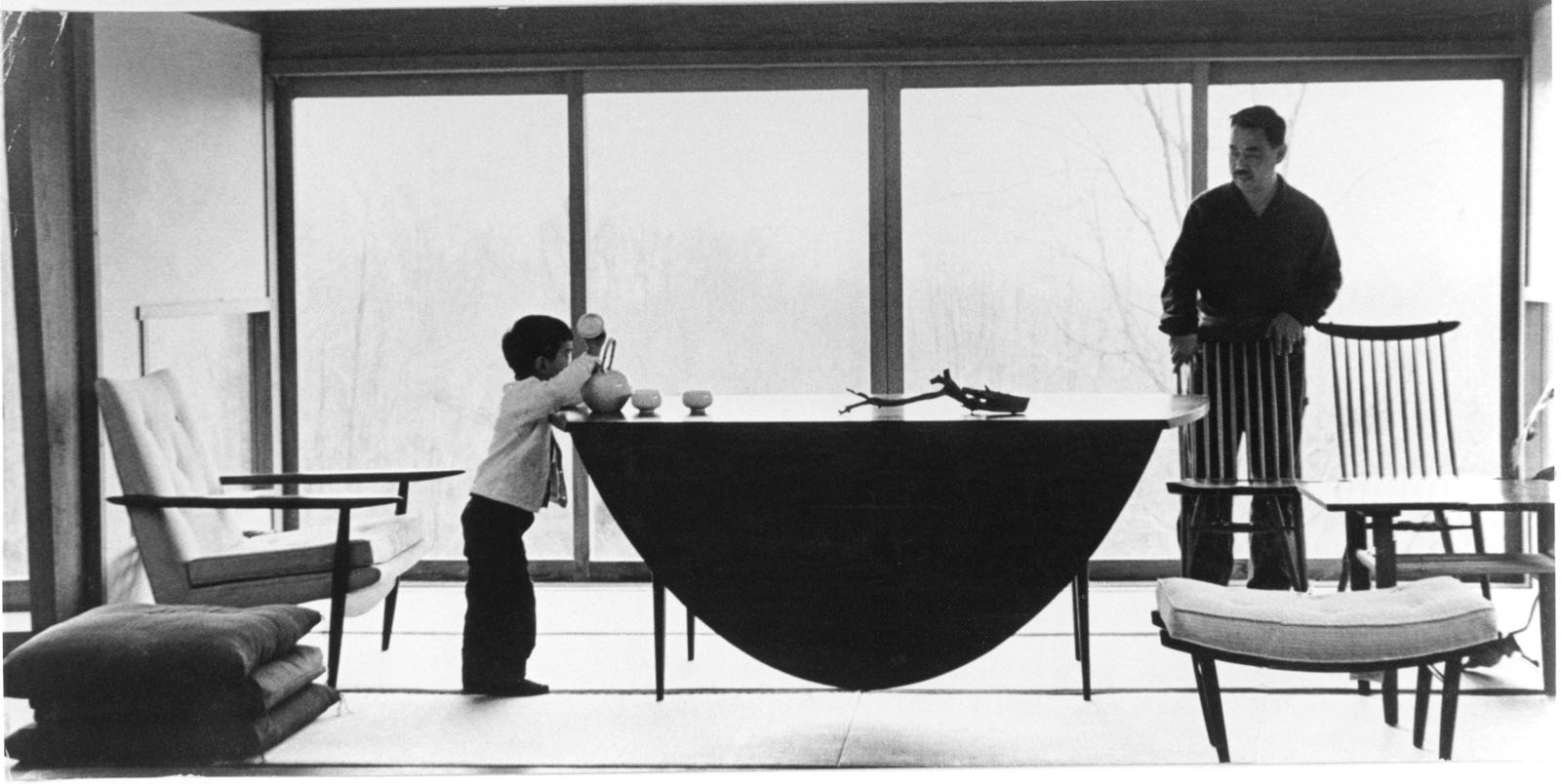

The newly completed Conoid Studio on the Nakashima property in New Hope served as a showroom for the first six Widdicomb pieces, which were photographed in 1958 with my inquisitive brother Kevin when he was about three years old (see photograph). Following are some excerpted quotations from the press surrounding the debut of the Nakashima Origins line for Widdicomb.

New York Times critic Cynthia Kellogg hailed it as a “New American look, a giant step in contemporary design . . . Despite its traditional inspiration Mr. Nakashima’s [furniture pieces] look as if they had been precisely designed by an architect and then hand-hewn out of tree trunks. The result is a boldly modern approach. Such furniture, with its insistent silhouettes and unadorned surfaces, calls for modern backgrounds.”[5]

The Philadelphia Sunday Bulletin quotes Nakashima: “For a long time to come—perhaps until the end of time—wood will be a material very dear to us. Bringing out the grain long imprisoned in a tree trunk is an act of creation. The true craftsman passes his hand over the satiny surface and finds God within.” According to the article, Nakashima had carefully studied the methods of production before designing this line, and it communicated “his tender, loving care of wood.” The article applauded not only Nakashima’s “craftsmanship but also his principles” manifested in mass-production.[6]

An article by Lois Hagen in the Milwaukee Journal also quotes Nakashima:

The love for the real nature of wood may be gained only by working directly with it. To bring out the beauty that has been hidden in the trunk of the tree for many years and even centuries, through hours of painstaking labor, is an act of creation in itself.

Although wood has infinitely rich possibilities it also has severe limitations. But to work within this framework of inspiration and challenge is one of life’s most rewarding experiences.[7]

Originally designed by George Nakashima for the Widdicomb Furniture Company Origins collection in 1958, this sofa was manufactured in 2012 by George Nakashima Woodworker, S.A., using the original drawings. Photographer: Christian Gianelli. Courtesy Mira Nakashima.

The Journal article called Nakashima a symbol of craftsmanship viewed as a creative force, “a moral idea, a way of life.” The article describes his Origins collection:

Strictly contemporary and without trace of foreign influence, the group is actually a collection of highly individual pieces. No two units match.

. . . Laurel . . . brought to Grand Rapids directly from Burma . . . dulls the knives used to cut it.

Walnut . . . has been cut to retain the light sap line that runs through each log. Nakashima deliberately plays up this streak, making it a dramatic asset in the design of drawer fronts and cabinet doors. . . .

. . . Spindles . . . are hand shaved . . . which makes them very appealing to the touch as well as to the eye. . . . [some of the arms have] inviting rounded contours [and are sometimes] wide enough to eliminate need for an end table.

A room divider is designed in a latticed pattern suggestive of a Mondrian nonobjective painting. . . .

Nakashima’s feeling for natural materials is a provocative one in this era of mechanization, when most of the forward looking design is based on new ways of using metal and synthetic materials.[8]

I love this quotation from Rita Reif of the New York Times : “In the massive forest of furniture designs introduced at the June markets this year, George Nakashima’s group for Widdicomb towered like a lonely redwood above the rest of the trees.”[9]

The Widdicomb-Mueller venture afforded Nakashima the opportunity to do certain things that are impossible in a workshop and to do them more elaborately. He declared that as man’s workaday world becomes more mechanized, his home must bring him closer to nature, saying, “Wood is one of the best ways of accomplishing this—it’s full of history, life and warmth.”[10]

George Nakashima, with son Kevin, in his New Hope, Pennsylvania, studio with several pieces from the new Origins collection. Published in Look magazine, April 25, 1959. Photographer: Arthur Rothstein. Courtesy George Nakashima Woodworker, S.A.

This is how Harriet Morrison described the Origins line:

Of greatest interest is the much heralded collection of furniture designed by George Nakashima for Widdicomb-Mueller . . . the American Look, which is interpreted as a new freedom in decorating . . . a certain rustic quality. The backwoods air is emphasized by free shapes, interesting wood grains, a hand hewn effect . . . provincial quality, but thoroughly citified in model rooms.[11]

An advertisement from department store B. Altman & Company declares that “Each piece is an original in the Origins Collection. Nakashima is the surprise ‘hit’ . . . the creations of this talented Japanese-American have won unanimous editorial praise. He calls his design method the ‘natural approach.’”[12]

From a 1958 House Beautiful article:

This wonderfully varied series of furniture was deliberately designed to let the beauty of wood speak for itself. George Nakashima, the designer, is a wood craftsman in the old sense. . . . For this factory-made group by Widdicomb-Mueller, he has worked out ways and means of using and finishing wood so that it can be mass-produced . . . this “Origins” group is astonishingly true to Nakashima’s custom-made standards.

There is no rigid matching of units to scream at you.

The combination of straight grain and burl exploit the pattern nature created in the tree trunk itself.

In a bedroom, the furniture creates a scene of quiet repose. Many gentle curves are introduced.

Strikingly original notes are struck in the fabric used . . . a brilliantly colored off-center stripe . . . a tone-on-tone hexagon pattern.[13]

George Nakashima wrote his only book, The Soul of a Tree, in 1981, received an award from the emperor of Japan in 1983, had his first retrospective show, Full Circle , in 1989 at the American Craft Museum in New York, and passed away in 1990. In 1984 he had acquired a great walnut log and dreamed of making peace altars from it for each of the continents of the world. He made the first one and installed it at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City in 1986. After his passing in 1990, we continued negotiations for another one in Russia, dedicated it at the fiftieth anniversary of the United Nations in 1995, and finally installed it at the Russian Academy of Arts in Moscow in 2001. There is a third one in Auroville, India, which was dedicated in 1996 and installed in the Hall of Peace there in February 2014. And some day we hope there will be one at the Desmond Tutu Peace Centre in Cape Town, South Africa.

When I wrote my book Nature Form & Spirit (Abrams, 2003), I felt that my father’s architecture on the New Hope, Pennsylvania, property was as important as his furniture. This year, the George Nakashima Woodworker Complex at New Hope was designated a National Historic Landmark. It was placed on the World Monuments Watch list in 2014. We hope that the furniture business will continue beyond the second generation into the third and fourth generations, to assure that our woodpile will continue to be put to good use for many years to come. We have managed to keep things going since 1990, as it feels like my father is still guiding us from behind that woodpile.

Notes

[1]. In 1950, the Widdicomb Furniture Company merged with the Mueller Furniture Company, also of Grand Rapids, to form the Widdicomb-Mueller Company. The merger was dissolved in 1960.

[2]. “Nakashima Designs Express ‘Naturalness’ in Modern Design,” in Grand Rapids: The Furniture Market for Fine Stores (Grand Rapids, MI: Grand Rapids Furniture Market Association, 1958), 56.

[3]. “Designers of Our Time,” in Grand Rapids: The Furniture Market for Fine Stores, 6.

[4]. “The Widdicomb Collection,” Widdicomb Distinguished Contemporary Furniture (Grand Rapids, MI: Widdicomb-Mueller Company, 1958), 1–2.

[5]. Cynthia Kellogg, “A New ‘American Look’ in Furniture Is Unveiled,” New York Times, June 14, 1958, 15.

[6]. Philadelphia Sunday Bulletin, June 15, 1959. Clipping from George Nakashima’s personal scrapbook.

[7]. Lois Hagen, “Designer Gives Factory Furniture Custom Appearance,” Milwaukee Journal, June 23, 1958, 2.

[8]. Ibid.

[9]. Rita Reif, “Craftsman’s Feeling for Woods Lends Greatness to His Furniture; Nakashima Designs, Hit of Markets, to Go on View Here,” New York Times, August 25, 1958, 25.

[10]. Quote by George Nakashima. Clipping from George Nakashima’s personal scrapbook.

[11]. Quote by Harriet Morrison. Clipping from George Nakashima’s personal scrapbook.

[12]. Advertisement by B. Altman & Company. Clipping from George Nakashima’s personal scrapbook.

[13]. “The Glorification of Wood,” House Beautiful, October 1958, 172–77.