Katherine Kirby White

In 1896, Oak Park, Illinois, lawyer and developer Thomas Gale asked architect Frank Lloyd Wright to design summer cottages in Whitehall, Michigan, for himself and his brother-in-law Walter Gerts. This was the auspicious beginning of Wright’s extensive work in Michigan. The design of the Gerts Cottage (1905)—double dwellings sited on either side of a creek with a connecting front porch—is considered a precursor of what would come to be Wright’s masterwork, Fallingwater. In 1932, Wright established the Taliesin Fellowship at his home in Spring Green, Wisconsin. During this period, Wright’s focus was on the creation of affordable homes for the average person. Like architect Richard Neutra, Wright experimented with applying Henry Ford’s assembly-line process to home construction. His goal was to provide good design at a reasonable cost, which he accomplished through his Usonian home concept. Michigan has one of the largest collections of Wright’s Usonian houses in the nation. It also has a number of homes designed and built by Taliesin fellows, who were often placed in charge of overseeing Wright’s construction sites. Subsequently they were asked by people in the communities they were working in to undertake new projects based on their own original designs.

Gregor S. and Elizabeth B. Affleck House, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, 1940. Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright. Photographer: James Haefner. Courtesy Michigan State Historic Preservation Office.

Michigan fully embraced Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural philosophy, from his organic Prairie style to his Usonian homes for the everyman. Today there are thirty-two known Wright-designed homes in Michigan, where his oeuvre epitomizes the transition from the Arts and Crafts to the Modern movement. The Meyer May House in Grand Rapids, completed in 1909, is regarded as Michigan’s “Prairie Masterpiece,” and is perhaps the most well known of his Michigan designs.[1] The bulk of his Michigan work, however, falls squarely into the midcentury and reflects his Usonian style.

Usonian Philosophy

During the Great Depression, Wright created a conceptual urban development he called Broadacre City, about which he wrote:

In the buildings for Broadacres no distinction exists between much and little, more and less. Quality is in all, for all, alike. The thought entering into the first or last estate is of the best. What differs is only individuality and extent. There is nothing poor or mean in Broadacres.

Nor does Broadacres issue any dictum or see any finality in the matter either of pattern or style.

Organic character is style. Such style has myriad forms inherently good. Growth is possible to Broadacres as a fundamental form, not as mere accident of change but as integral pattern unfolding from within.[2]

Broadacre City was a model for living. Fireproof synthetic building materials, copper roofs, and prefabricated utility stacks were the bricks-and-mortar means of shelter, but the vision of Broadacre City offered much more. “Diversity in unity,” in which form and function are one, economic independence, and “a subsistence certain,” Wright determined would all be accomplished.[3] Apart from physical needs, Wright explained that, “sociologically, Broadacres is release from all that fatal ‘success’ which is, after all, only excess.”[4]

Though Broadacre City was never actually built, the ideas behind it served as the foundation for a type of planned utopian community Wright called “Usonia.” It was Wright’s attempt to establish a new way of living through the construction of streamlined, affordable houses in a decentralized and modernized communal living development. Usonia was to be a rejection of the cramped, urban American landscape; it capitalized on the ready availability of the automobile to whisk Americans out of the urban and into the suburban landscape. It fully embraced new technology—radio, telephone, and the automobile—which necessitated less urban proximity.[5] Wright, who had great respect for the work of Henry Ford, emphasized standardization and assembly-line production as well as the use of new postwar technology. Usonia was Wright’s version of social reform, a renewed democratization of land use, and his take on urban renewal, even before Robert Moses had made his significant mark on New York City’s landscape.

The first practical application of Wright’s Broadacre concept, Usonia 1, was to be developed near East Lansing, Michigan. However, it didn’t materialize and only three Usonian communities were ever actually developed and built. Two were developed in southwest Michigan: The Acres and Parkwyn Village. The third, built outside Pleasantville, New York, was known as Usonia.

Curtis and Lillian Meyer House, The Acres, Galesburg, Michigan. Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright. Photographer: Todd Walsh. Courtesy Michigan State Historic Preservation Office.

Plat map of Parkwyn Village in Kalamazoo, Michigan, showing circular lots designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, 1949. Courtesy Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs.

Usonian Communities: The Acres and Parkwyn Village

A group of scientists from the Upjohn pharmaceuticals company based in Kalamazoo, Michigan, saw the value in Frank Lloyd Wright’s dream of community living as explained in his Usonian manifesto and visualized in his plan for Broadacre City, and hoped to create such a place.[6] As they began looking for a suitable piece of land to develop, the group split. Half decided to purchase seventy-two acres about ten miles east of Kalamazoo in Galesburg. This community became known as The Acres (also known as Galesburg Country Homes). The other half, thinking that site was too remote, found a suitable site within Kalamazoo’s city limits. This development was named Parkwyn Village. Working together, both groups called upon Wright to visit their proposed sites, which he did in March 1947.[7]

Lillian Meyer, a Wright enthusiast and the wife of an Upjohn scientist, wrote to Wright in 1946 regarding the Galesburg site, saying, “Our group consists of five families who have purchased 71 acres of rolling land . . . ten miles from downtown Kalamazoo . . . I hope that you will be interested in doing our houses and site. We are all enthusiastic and will be keenly disappointed if we cannot have a Wright house.”[8] Later that year, six of the group journeyed to Taliesin in Wisconsin to discuss their proposed development with Wright.[9] The Acres was designed to comprise twenty-one single-acre, circular family lots. These circular lots were meant to increase a sense of community within the development. The spaces between the circular lots were to become small communal parks. In the end, only five residences were actually built in the community, four designed by Wright himself. The fifth was designed by Taliesin fellow Francis “Will” Willsey, a graduate of the University of Michigan. Willsey spent two years at Taliesin before taking a job with a Kalamazoo architectural firm. The Acres homeowners self-built their houses using an early version of Wright’s Automatic Block System from a Taliesin mold, which cut costs and utilized concrete to circumvent the postwar materials shortage.[10] True to Wright’s Usonian ideal of affordability, all homes in The Acres were constructed using mahogany, a less costly alternative to Wright’s favored cypress.[11]

Though its roots are nearly identical to The Acres, the Parkwyn Village site has a much different appearance. Wright initially designed the lots for both developments to be circular, which caused the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to deny funding. While the residents of The Acres were able to find alternative funding and keep the circular lot patterns, the residents of Parkwyn Village were not; they were forced to concede to the FHA and adopt more traditional lot shapes.[12] Wright designed the plan for the forty-seven-acre Parkwyn Village site, located in southwest Kalamazoo, during his 1947 visit to both communities. He specifically planned for forty homes to be built in Parkwyn Village, including five Usonian concrete block residences of his own design. From the beginning it was envisioned that architects other than Wright would design homes in the development.[13] Today, forty houses exist in the neighborhood, including four Wright-designed homes completed between 1948 and 1949 as well as residences designed by a Wright-inspired local architect, Norman Carver Jr.

Alma Goetsch and Kathrine Winckler House in Okemos, Michigan, 1940. Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright. Photographer: Steve Vorderman. Courtesy Michigan State Historic Preservation Office.

Single-Family Usonian Residences

Although Wright’s Usonian communities are among his grandest concepts, his Usonian stand-alone homes were far more influential and prolifically built. The Usonian single-family home attempted to incorporate many of the Broadacre City ideals into a single building. The suburban emphasis was easily manifested as Wright guided his clients towards open, rural landscapes not found in the urban context. His designs often included a carport—the reliance on the automobile visually represented. The affordability and sustainability of the Usonian home was accomplished by material choices such as dyed concrete flooring rather than the terrazzo Wright favored; concrete block construction, chosen for its wartime availability and thermal properties; and the option for clients to cut costs by self-building their homes. Although in a single-family Usonian residence Wright lost the ability to control all surrounding elements as he could in a community development, each single Usonian residence became a microcosm of Wright’s broader Usonian ideals.

Michigan is home to more of Wright’s Usonian residences than any other state: an estimated twenty-two homes. Eight are located within Parkwyn Village and The Acres; the rest are stand-alone, single-family residences located around the state in Ann Arbor, Benton Harbor, Bloomfield Hills, Detroit, Marquette, Northport, Okemos, Plymouth, and St. Joseph. The Abby Beecher Roberts House (1936) in Marquette has the distinction of being constructed by architect John Lautner for his then mother-in-law. Two of Michigan’s most well-known Usonian homes are the Alma Goetsch and Kathrine Winckler House (1939) located in Okemos, Michigan, and the Dorothy H. Turkel House (1955) in Detroit.

Alma Goetsch and Kathrine Winckler House, Okemos, Michigan

Wright’s Usonian designs fall into five general shapes: polliwog, diagonal, in-line, hexagonal, and raised.[14] The Goetsch-Winckler House is often used as the prime example of Wright’s in-line Usonian plan. Alma Goetsch and Kathrine Winckler were professors of art at Michigan State College (now Michigan State University). In 1937, after learning that Wright had completed what would come to be known as his first Usonian house in Madison, Wisconsin, Goetsch and Winckler realized that owning a moderate-cost, Wright-designed home was no longer an impossibility.[15] Initially, the Goetsch-Winckler House was planned to be part of a larger community called Usonia 1, which was to be Wright’s first practical application of his Broadacre City theories to be developed on seventeen acres purchased by six professors at Michigan State College. However, their private financing fell through, which necessitated a bank loan triggering FHA approval. The FHA denied the project funding, claiming, “the walls will not support the roof; the floor heating is impractical; the unusual design makes subsequent sales a hazard.”[16] Goetsch and Winckler found a new site and their Wright-designed home was completed in 1939 for approximately $6,600, an affordable sum for an architect-designed home in the late 1930s.[17] The house is horizontally emphasized, with clerestory windows in the kitchen to allow natural light, scored concrete slab flooring, two personalized bedrooms, and Wright’s mandatory Usonian carport.

Dorothy H. Turkel House, Detroit, Michigan, 1955. Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright. Photographer: Brian D Conway.

Dorothy H. Turkel House, Detroit, Michigan

The Dorothy H. Turkel House is the only Wright-designed structure within Detroit’s city limits and the only example of a two-story Usonian residence constructed using his Automatic Block System.[18] Built in 1955, the Turkel House blurs the lines between indoor and outdoor space, perhaps more than any other Wright-designed residence in Michigan. Approximately five hundred windows, the majority enclosed in structural concrete blocks, create a remarkably bright and airy interior space. Although air conditioning was common at the time the Turkel House was built, Wright opted to use natural rather than mechanical methods to cool the house. Increased circulation created by the multitude of windows and doors, a cantilevered balcony, and wide overhanging eaves—in combination with the shade of trees planted to surround the house—kept it at a comfortable temperature. The Turkel House was designed as an in-line plan, however a playroom was added, creating a short L-shaped plan.

Taliesin Fellows in Michigan

Wright’s contributions to Michigan’s architecture extend beyond his actual work in the state. His Usonian homes in the region created a demand that resulted in a fertile landscape for Wright’s apprentices at Taliesin. Dozens of Taliesin fellows practiced in Michigan, designing hundreds of structures, and their influence still reverberates throughout the state today. Some of the most intriguing examples of organic architecture in Michigan were designed by architects who spent time at Taliesin. Most notable is the Alden B. Dow Home and Studio in Midland. Three other significant examples include the Frank and Dorothy (Feinauer) Ward House in Battle Creek, designed by Yuzuru Kawahara; the now-demolished Snow Flake Motel in St. Joseph, designed by William Wesley Peters; and the Church of St. Mary in Alma, also designed by William Wesley Peters.

The Frank and Dorothy Ward House, Battle Creek, Michigan

The Ward House was built in 1952 on the southwestern shore of Goguac Lake in Battle Creek, Michigan. The architect, Taliesin fellow Yuzuru “LeRoy” Kawahara, had been in Michigan assisting Taliesin fellow Will Willsey with a commission when Frank Ward, hearing of Kawahara’s connection with Wright, asked him to design his home.[19] The house is constructed in an L-shaped plan, similar to Wright’s polliwog Usonian plan, in which the exterior of the “L” faces the lakefront. It is constructed entirely of brick, cypress planks, and an abundance of glass. Ninety-seven windows, eighty-five of which have lake views, create a luminous interior. Kawahara served as the general contractor as well as the architect.[20] He was involved with every aspect of the house’s design. An interesting twist in the design of this particular house is the elaborate owner-designed fallout shelter in the basement, which Kawahara helped to construct. Frank Ward was a colonel in the U.S. Army during World War II, and during the Allied occupation after the war was sent to Hiroshima to research ground zero and the structures that had survived the atomic bomb so that he could assist in the development of national standards for bomb shelters built in the United States. After the war, Ward became the civil defense director for both the City of Battle Creek and the State of Michigan.

Like Wright, Kawahara not only utilized the organic style, but form followed function at each turn and he paid special attention to the individual needs of his client. Kawahara clearly utilized much of what he had learned from Wright at Taliesin, from the Usonian floor plan to his emphasis on the importance of each design element, down to the light fixtures.

The Snow Flake Motel, St. Joseph, Michigan

The Snow Flake Motel, located in St. Joseph, Michigan, was designed by William Wesley Peters and built in 1961. Peters was not only a Taliesin fellow, but was chief architect of Taliesin Associated Architects as well as Frank Lloyd Wright’s son-in-law. Sahag Sarkisian, a local oriental rug dealer, contacted Wright in 1958 about designing a luxury motel. Although Wright reportedly flew over and approved the proposed site on the Red Arrow Highway shortly before he died in 1959, it was ultimately Wes Peters who was responsible for the design.[21]

The motel complex appeared in the shape of a snowflake—or a six-pointed star—that encompassed more than six acres (see photographs). It boasted fifty-seven guest rooms, a cocktail lounge, conference center, a courtyard garden, and a hexagonal swimming pool with a steel geodesic dome covering. It was connected to a smaller hexagonal wading pool by a long, narrow reflecting pool with fountains that jetted at regular intervals and were lit at night. Light poles, awnings, and metal gates all repeated the snowflake motif, which was said to have cast shadows on the surrounding paved patios throughout the day.[22] The guest rooms alone were a marvel of the time; elements that are ubiquitous today—floor-to-ceiling windows, color televisions, and individual ice machines in each room—were progressive in 1961. Tragically, family disaster and subsequent neglect led the Snow Flake Motel into disrepair and it was demolished in 2006.

The Church of St. Mary, Alma, Michigan

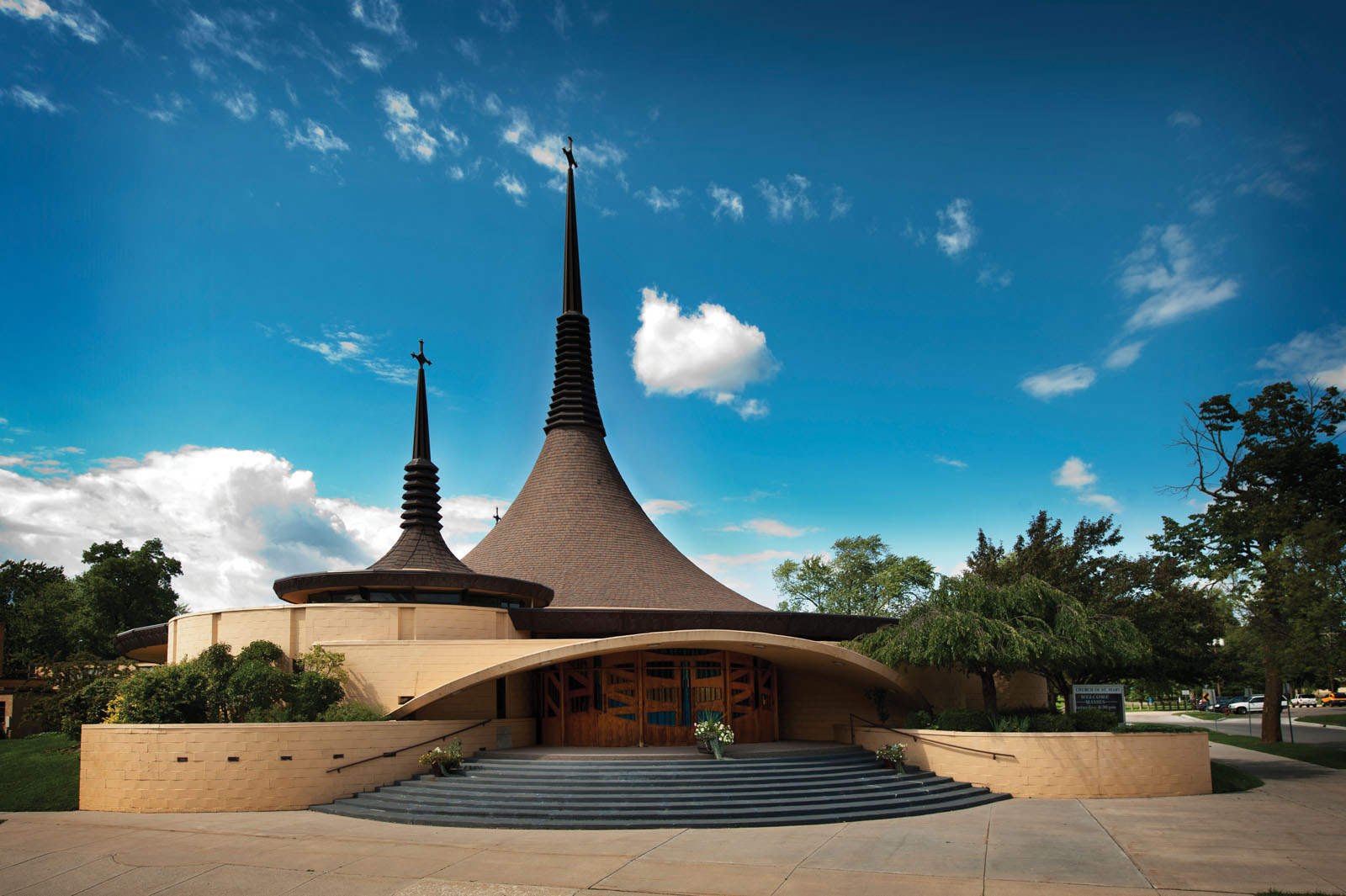

The Church of St. Mary, located in Alma, Michigan, was designed by William Wesley Peters and built in 1969. Peters had recently completed a residential commission for parishioner John Hiemenz, who recommended Peters when the congregation decided to build a new church.[23] Dedicated in 1970 and completed for approximately $575,000, the Church of St. Mary is like no other Catholic church in the state of Michigan. Soaring conical roofs and a series of interlocking curved walls surprise the viewer as the building seems to organically sprout from the ground. Peters’s play on the concave and convex forms gently guide the eye to the front entrance, simultaneously beckoning the viewer into the church. Masterful stained glass windows are found inset into the large front doors, and smaller stained glass panels allow light to enter behind the altar at the rear of the structure. The church complex encompasses an entire city block in the small town of Alma, and comprises the sanctuary, a contrasting L-shaped rectory, and a school.

The Church of St. Mary, Alma, Michigan. Architect: William Wesley Peters. Photographer: Steve Vorderman. Courtesy Michigan State Historic Preservation Office.

Notes

[1]. William Allin Storrer, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright: A Complete Catalog, 3rd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 146.

[2]. Frank Lloyd Wright, “Broadacre City: A New Community Plan,” The City Reader, 5th ed., ed. Richard T. LeGates and Frederic Stout, Urban Reader Series (New York: Routledge, 2011), 346.

[3]. Ibid., 347–48.

[4]. Ibid., 346.

[5]. Ibid., 345.

[6]. Peggy Guthaus, “AIA Notes Wright Designs Here,” Kalamazoo Gazette, December 13, 1984, sec. B.

[7]. Ann Paulson, “Living Wright: Christine Weisblat Recalls the Adventure of Building and Living in One of Mr. Wright’s Usonians,” Welcome Home, September/October 1994, 24.

[8]. Ibid.

[9]. Storrer, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 295.

[10]. Robert C. Twombly, Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life and His Architecture (New York: Wiley, 1979), 265.

[11]. Storrer, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 295.

[12]. David Woodruff, “The Wright Projects,” Kalamazoo Gazette, December 25, 1985, B8.

[13]. Twombly, Frank Lloyd Wright, 265.

[14]. John Sergeant, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses: The Case for Organic Architecture (New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1976), 41.

[15]. Diane Tepfer, “Alma Goetsch and Kathrine Winckler: Patrons of Frank Lloyd Wright and E. Fay Jones,” Woman’s Art Journal 12, no. 2 (1992): 16.

[16]. Frank Lloyd Wright, “Frank Lloyd Wright,” Architectural Forum 88 (January 1948): 80.

[17]. Ibid.

[18]. Storrer, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, 392.

[19]. Dave Paulson (longtime caretaker of the Ward House), interview by Katherine Kirby White, November 5, 2012.

[20]. Ibid.

[21]. Carlene Lymburner (former owner of the Snow Flake Motel), interview by Glory-June Greiff, December 1, 1997.

[22]. Glory-June Greiff, “Snow Flake Motel,” nomination form for National Register of Historic Places (1998), sec. 8, 4–6.

[23]. “Church Celebrates 100th Year,” [Mt. Pleasant] Morning Sun, June 25, 2005.