Becoming Benny

THE DEVELOPMENT OF JACK BENNY’S

CHARACTER-FOCUSED COMEDY FOR RADIO

Anticipation mixed with anxiety in the small, glass-enclosed broadcasting studio installed in the old roof garden situated atop Broadway’s New Amsterdam Theater on Monday night, May 2, 1932. Beginning at 9:30 P.M. EST, the inaugural episode of Canada Dry Ginger Ale’s half-hour radio program aired live, carried over a network of NBC Blue radio stations covering the eastern United States. The only audience members were representatives from the show’s sponsor, advertising agency, and network. The program’s concept and cast had been assembled for Canada Dry by NBC executive Bertha Brainard as a new direction in sponsorship for the company, which had previously underwritten a dramatic (and violent) adventure series set in the Canadian Rockies.1 Canada Dry’s advertising agency N. W. Ayer & Son billed the new show as “30 minutes of music and quips” featuring six numbers played by New York bandleader George Olsen and his orchestra and sung by his spouse, Ziegfeld Follies star Ethel Shutta. Already widely familiar to radio listeners, they were considered to be the main attraction of the show.2 The music would be interspersed with brief monologue segments performed by thirty-eight-year-old vaudeville veteran Jack Benny, who was introduced as “that suave comedian, dry humorist and famous master of ceremonies.”3 In his first performance for Canada Dry, Benny told a series of jokes drawn from his well-honed stage routine, offering informal and genially self-deprecating comments on personal experiences, such as his Hollywood adventures and the mediocrity of his girlfriend, who posed for the “before” in “before and after” photos. By the conclusion of his fourth biweekly episode, Benny queasily realized he had used up nearly every monologue he had perfected over fifteen years in vaudeville, and more broadcasts lay ahead of him.

The new Canada Dry show joined a rapidly increasing number of variety-comedy programs on primetime network radio. While music had been the dominant program form of the previous five years, the entertainment trade press noted that comedy was growing as a less expensive option for sponsors weary of paying for high-priced orchestras and temperamental crooners. New shows in the 1932 season featured not only newcomer Jack Benny but also other vaudevillians such as George Burns and Gracie Allen, George Jessel, Fred Allen, and Jack Pearl. Most, like Benny, were serving as “emcees” (short for M.C. or master of ceremonies) for programs that mixed music, comedy, and advertising messages. The new entrants joined such already-popular variety programs as those hosted by Rudy Vallee for Fleischmann’s Yeast, Ed Wynn for Texaco, and Eddie Cantor for Chase and Sanborn Coffee.4

The burgeoning popularity and financial success of commercial network radio was the one bright spot in an American economy sliding ever further into the Great Depression. The unemployment rate was nearly 25 percent, banks were closing left and right, and major industries had ground to a standstill. The entertainment world was hit especially hard. The majority of Broadway theaters were shuttered, major league baseball teams were playing in stadiums emptied of spectators, and vacation resorts appeared abandoned. Even the movie studios and picture palaces, which with the tremendous popularity of “talkies” had seemed immune to the economic crisis, now experienced a devastating downturn in business.5 The advertising business (also tremendously hard-hit) found that clients who promoted their products on radio programs (especially inexpensive consumer goods like tobacco, soap, and coffee) were seeing enormous sales gains.6 The speed and extent to which previously unknown performers like Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll had become nationally famous as “Amos ’n’ Andy” astonished entertainment veterans like Benny (the duo hadn’t paid their dues by honing their act for years in theaters in the hinterlands).7 The gloating of the Pepsodent company, whose toothpaste’s previous meager sales skyrocketed when it began sponsoring the Amos ’n’ Andy program in 1929 was impossible to ignore. The pull of this growing entertainment medium, coupled with the push of steeply declining opportunities on Broadway and in vaudeville due to the Depression, propelled the apprehensive Benny to try his hand in radio.8

Facing the daunting challenge of filling radio’s unprecedented, ferocious demand for new content, Jack Benny initially struggled, but ultimately thrived in the new medium by developing new approaches to comedy. Benny and scriptwriter Harry Conn began to craft a personality-based radio variety program, drawing on Benny’s vaudeville style and exploring new (to them) comic constructions of what contemporary critics termed character comedy and comedy situations. Experimenting as the program progressed from week to week, Benny and Conn expanded the narrative world of the show. They began developing comic identities for the major performers (orchestra leader, vocalist, and announcer) who stood around the microphone. Framing the group as workers putting on a radio show, Benny and Conn developed a personality for each of them that blended reality and fiction. The cast became a stable of recognizable, quirky-yet-likeable continuing characters who could bounce off each other in informal exchanges in the studio or interact in situations from visiting the zoo or having dinner at a cast member’s home to performing a parody of a popular new film. This variety greatly reduced Benny and Conn’s reliance on pat monologues and standard joke telling. What they developed was a forerunner of the situation comedy, a genre that would become much more prominent only fifteen years later in radio and television broadcasting in response to changing industrial practices and cultural norms.9

The duo could have created comic content for the program while leaving the emcee as the star, a dominant figure who was fed straight lines by subordinates, or by making him a pleasantly bland father figure who rode herd over his workplace family. Instead, over a three-to-four-year period, Benny and Conn gradually transformed the Jack Benny persona. Writer and performer transitioned the role from the vaudeville character of a suave but self-deprecating monologist (called by vaudeville critics the “sleekly bored joker”) to that of a vainglorious, hapless Fall Guy, a “negative exemplar,” in historian Steven Mintz’s terms, roundly (and ritually) roasted by his stable of zany stooges.10 Benny and Conn turned the humor around. Benny the emcee became the butt, not the mouthpiece, of the acerbic comic lines. The “Jack Benny” character of radio fame was their greatest creation. Even when their partnership unraveled in 1936, they had solidified Benny’s place as the premiere comedian in American radio broadcasting.

BENNY’S EARLY VAUDEVILLE PERSONA

Jack Benny had already spent more than twenty years developing a vaudeville identity that brought him, if not immense stardom, solid success as a musician who had transitioned into a humorist who held a violin in one hand and a cigar in the other as he joked. Working as a “single” who occasionally interacted with an assistant or other acts on the bill, Benny joined the expanding group of informal, modern vaudeville hipsters whom we would know later as stand-up comics. Benny’s twist to the genre involved creating a “middling” personality who was neither young nor old, wealthy nor poor. He was not loud or buffoonish, and he related to a homogenizing American audience as much more Anglo-American than Jewish or ethnic.11 He was a Midwestern variant of what vaudeville historians term “the Voice of the City.”12 Variety critic Robert Landry later asserted that Jack Benny’s stage manner had always seemed “big time,” even as it was perfected in local theater orchestras, military camp shows, and small-time vaudeville in the 1910s and early 1920s:13

[Benny’s] style was subdued, his delivery one of the first examples of modern “throw away.” He was poised, unhurried, seemingly effortless. . . . He was not an ad libber, in the general sense. He prepared his stuff ahead but changed it frequently, infused it with topical allusions. But he sounded ad lib.

Landry acknowledged that Benny’s appeal was nevertheless somewhat limited, because his act “demanded too much attention and quiet” to thrive either in noisy metropolitan night clubs or among the rough and tumble milieu of vaudeville comics in the hinterlands.

Reviews of Benny’s routine in the early 1920s commended the “reserve, poise and personality” of the monologist.14 “Jack Benny with his slow, easy patter, gets his crowd before he is well under way,” commented a typical critic, who also mentioned the mediocrity of Benny’s jokes.15 When he appeared in 1925 at New York’s Palace Theater, vaudeville’s pinnacle, Billboard praised Benny’s “droll delivery,” but also labelled his routine as being “a cross between the Frank Fay and Ben Bernie styles.”16 Initially, as Ben K. Benny (his early stage name), in his act Jack Benny had superficially resembled deep-voiced bandleader Ben Bernie, who grasped a fiddle and embellished the punch lines of his jokes with the catchphrase “yowza yowza!”17 Bernie pressured the younger Benny to further modify his stage name to widen the perceived differences between them.18 The comparisons with Frank Fay continued, however, as Jack Benny unabashedly modeled his act on that of the well-known Irish-American comic. When Benny returned to the Palace in April 1926, Variety complimented his “excellent material and delivery” and his witty interplay with other performers: “Stanley and Birns [the next act] came out early and asked to tell a story in Benny’s spot. Benny’s comments on the story were real funny. It was likeable nonsense and a yell when Benny stopped [them] as he recognized it as a stag story.”19 Benny regularly reenacted this routine with a female assistant whispering the salacious story in his ear, so that he could flirtatiously dance between polite and sexually suggestive humor. When he incorporated it into a 1928 Vitaphone talkie short, a reviewer snarkily noted its similarities to a Frank Fay routine—“They can fight out who did it first.”20

Frank Fay’s urbane manner made him one of the most prominent and highest-paid performers in vaudeville.21 He was one of the first to enact the emcee role at the Palace and the nation’s other top theaters. Emcees had existed previously in minstrel shows (where they were called interlocutors) and in British music halls (where they were called comperes), but Fay was said to have coined the term used in American vaudeville.22 The emcee role was an outgrowth of Fay’s innovative monologue act. Fay was one of the first stage comedians to eschew outlandish costumes, makeup, props, and broad physical shtick. The debonair redheaded, blue-eyed Fay dressed with impeccable, aristocratic style and moved with a feminine grace. His timing and delivery were judged “masterly.”23 He was a “boastful big city boulevardier” with a breezy delivery and relatively restrained, soft-spoken demeanor that covered a rapier wit. “Faysie” had a devastating ability to ad lib insults that could destroy any heckler in the audience. A Life Magazine profile described “his cockiness and his conceit, . . . the gentle smile, the quizzical lift of the eyebrows, the sweet voice and then the dirty crack.”24 Fay did not depend on strings of one-liners, but was a storyteller whose collection of whimsical and digressive tales were peopled with everyday individuals such as a family that obsessively saved string. Fay also sang stanzas of current songs like “Tea for Two,” stopping to dissect the absurdities of the lyrics along the way. He was elegant, suave, and superior—and made sure the audience knew it, through his wicked repartee and stinging quips, perfecting what a critic called “an odd combination of humor and elegance.”25 Fay’s act was widely admired and copied by other comics, but offstage he was reviled for his bigotry, his alcoholism, and his massive ego (he called himself “Frank Fay, the World’s Greatest Comedian”). Fellow comic Fred Allen once cracked, “The last time I saw Fay, he was walking down Lover’s Lane holding his own hand.”26

Vaudeville acts had traditionally followed each other on stage in quick succession, identified in printed programs and by title cards placed on an easel at the side of the stage. But as attendance began to dwindle, vaudeville managers began to add an extra attraction—a headliner such as Fay, Jack Benny, Julius Tannen, or George Jessel to present the show. The lead comic would appear not only in his own spot, but also throughout the bill, introducing the acts, interacting with (or interrupting) other performers, ad libbing patter between the spots, and filling time if there were delays in the show. Some critics complained that this restructuring slowed the pace of the program, but the emcee’s performance made the disparate parts of the program seem more interconnected. Benny approached the emcee role with a collaborative spirit, whereas Fay took the opportunity to turn the spotlight on himself and dominate the entire proceedings. Benny did borrow Fay’s quiet charm, elegant manner, and womanly walk, but, lacking his quick and inventive tongue, replaced Fay’s arrogance and ad-libbed putdowns with carefully crafted lines that sounded off-the-cuff, and included a subtle self-deprecation. “Benny’s opening line, which he used for years, was celebrated,” recalled vaudeville historian Maurice Zolotow. “He would casually lope toward the center of the stage, tuck his violin under his arm, brush his hair back with his left hand, and inquire of the maestro, ‘How is the show?’ ‘Fine up to now,’ the maestro would reply. ‘I’ll fix that!’ Benny would say.”27

Jack Benny rivaled Fay as one of the most frequent emcees at the Palace between 1927 and 1931.28 “Benny knows the Palace and its audiences there as few others do, knowing what else they like besides actor and show biz gags,” noted a reviewer, who also voiced the concern mentioned by other critics, that Benny struggled to find enough new material to last through repeated viewings.29 In Chicago, “Jack Benny, who had acted as M.C. throughout the bill, was refreshingly humorous in his easy, graceful way, his chatter and violin playing both going over big.”30 Vaudeville appeared increasingly unstable, however, so Benny experimented with other media. He appeared on Broadway in the 1927 Shubert Brothers’ revue The Great Temptations, but felt that the predominance of “blue” humor did not complement his style.31 He also tried his hand at the movies, riding the wave of talent from vaudeville and the stage flowing to Hollywood with the coming of talkies. However, after playing a prominent role as the emcee of MGM’s Hollywood Revue of 1929, his subsequent film roles (and reviews of his performances) were lackluster. Nevertheless, Benny kept trying to play up his film connections.

In 1930 and 1931, Benny moved his act between films, vaudeville venues, and cavernous picture palaces, which began adding live stage acts to their movie shows to shore up attendance. Entertainment forms were converging, but Benny did not seem to fit comfortably into any of them. Playing the Palace, Benny asked to bebilled as “the cinemaster of ceremonies.”32 Skeptical critics expressed concern that Benny’s work was too quiet and low-key to take command of 5,000-seat auditoriums. Although he did moderately well, devising some punchy additions to enlarge the scale of his act (Zouave soldiers, Japanese acrobats, comeuppance from the abrupt start of the film program onscreen), a reviewer of his show at New York’s Capital Theater was still unconvinced. “Benny is still the suave and clever emcee working all through the show to keep it pieced together effectively. His suaveness, then, tends to slowness, which hardly helps a presentation in a ‘deluxer.’ The type of entertainment that goes is that which is served speedily and peppily.”33 Benny was at a career crossroads, as he wandered among various venues and media forms, trying to find the most advantageous platform for his particular skills. Worsening economic conditions of the early 1930s made the search more nerve wracking.

In 1932, radio and advertising executives like NBC’s Brainard, scanning the horizon for talent that might best adapt to broadcasting’s needs, considered Jack Benny, although they were not initially very enthusiastic about him. Neither network brass nor sponsor’s agencies were certain what styles and types of performers would work on the radio—many preferred the loud brashness and quickness of other comics and the stentorian tones of tuxedoed announcers. NBC had actually approached literary humorist Irvin S. Cobb prior to contacting Benny, but Cobb’s salary demands were too high. Executives probably noted the affinities Benny’s stage act had with aural presentation—Benny produced most of his humor through low-key language and smooth, superbly timed delivery of his lines. He was not a primarily physical or visual comedian getting laughs through broad facial expressions, costume, or slapstick body movements. Benny engaged in quiet, intimate joking, confiding in the audience as if it were a small group, similar to the methods of the “crooning” singers like Bing Crosby and Rudy Vallee who were becoming popular through radio appearances. On the other hand, Benny’s droll stare at the stage audience, with hand to his cheek, which silently communicated his frustration and won viewers’ sympathy, would be lost on radio listeners. It would only reemerge in the early 1950s to embellish his comedy routines on television.

CHALLENGES OF THE INITIAL CANADA DRY PROGRAM

As Benny began the twice-weekly broadcasts of Canada Dry’s new musical comedy radio show in May 1932, it seemed that not only he, but the sponsor, ad agency, and network were almost shockingly naïve about how much labor Benny’s role might entail. The orchestra and vocalist had large musical catalogs from which they could draw new tunes to perform, but if Benny was to do more than introduce the title of the next song, he was going to need fresh material every episode. Apparently no provisions were in the original plans for the program to hire writers. The executives must have assumed Benny ad-libbed or wrote his own humorous asides. As a popular emcee, Benny had experience in creating short gags and exchanges with vaudeville performers, but he was used to repeating similar patter for different audiences the whole week of the engagement, either getting new performers to work with or a new city to play in the following week. No one involved with the Canada Dry Program had entirely thought through how a twice-weekly show with the same performers and the same audience might work.

FIGURE 3. “Bandleader George Olsen and vocalist Ethel Shutta were the original draws for the Canada Dry Ginger Ale radio program. Jack Benny successfully coached them both into becoming fine comedy dialogue readers.” New Movie Magazine, September 1932, 60. Accessed from Media History Digital Library http://archive.org/stream/newmoviemagazin06weir#page/n311/mode/2up

The first live episode demonstrated the promise and the drawback of the concept. In seven short monologues interspersed between the songs, Benny presented himself as a suave, urban, and thoroughly Americanized fellow who was witty and personable, a wisecracker who was self-centered but who self-deprecatingly understood that his attempts at boastful egotism would end in mild humiliation. Benny exchanged a little banter with orchestra leader George Olsen and singer Ethel Shutta as he introduced them. Nervous awkwardness of the new endeavor was apparent in Benny’s doing most of the talking and their very brief responses to standard vaudeville jokes, such as ribbing the age of Olsen’s automobile. Benny worked from a script; he wanted a written structure to guide him to make sure he was organized and that the jokes could be carefully pored over and crafted into polished gems.34 He delivered his lines, though, in such an easy, nonchalant manner that listeners may have thought he was speaking off-the-cuff. Studies of Benny’s career usually point out the assertive way that, even in this first episode, he wove the middle-of-the-program advertising messages into his monologues, entwining a playful (and fairly unusual) mocking tone toward the product in the same way he told self-deprecating stories about himself. Benny’s introductory monologue was probably drawn from when he played at the Palace, but with the added twist of a backhanded plugging of the sponsor’s product:35

Ladies and gentlemen, this is Jack Benny talking, and making my first appearance on the air professionally. By that I mean, I am finally getting paid, which will be a great relief to my creditors. I really don’t know why I am here. I’m supposed to be a sort of master of ceremonies and tell you all about the things that will happen, which would happen anyway. I must introduce the different artists, who could easily introduce themselves, and also talk about Canada Dry made to order by the glass, which is a waste of time, as you know all about it. You drink it, like it, and don’t want to hear about it. So ladies and gentlemen, a master of ceremonies is really a fellow who is unemployed and gets paid for it.

In the second and third episodes of the Canada Dry Program, with a dash of desperation, Benny provided brief descriptions of his fellow radio performers that again drew on standard vaudeville insult-humor patter—George Olsen was penurious, Ethel Shutta lied about her age, the boys in the band were drunkards, and announcer Ed Thorgerson resembled a Hollywood playboy with slicked-back hair and a thin mustache. (It “looked like he’d swallowed all of Mickey Mouse but the tail,”36 Benny quipped.) But the others were given few lines to speak. Benny appealed to his unseen listeners directly, asking if there was anybody out there and reintroduced himself halfway through the show. In the second week, he opened the program with “Hello somebody. This is Jack Benny talking. There will be a slight pause while you say ‘what of it?’ After all, I know your feelings, folks, I used to listen in myself.”37 He closed with, “That was our last number of our fourth program on the 11th of May. Are you still conscious? Hmm . . .?”

Variety’s reviewer in May 1932 sensed Benny’s nervousness, but tried to be encouraging, noting “there’s no reason why a clever, intimate comedian of Benny’s type shouldn’t hit over the air. Essentially he has everything it takes, from an excellent speaking voice to the right kind of delivery.” Nevertheless, the reviewer was unenthusiastic about the integration Benny was trying to bring to the separate elements of music, comedy, and advertising in the show, recommending that Olsen “should leave all the talking to Benny.” The comic advertising was also disturbing: “Plug angle was considerably overdone here, with Benny handling it throughout. He pulled some pretty obvious puns, such as “drinking Canada Dry”. . . . Right now the subtle spotting of the plug should be handled with silk gloves.”38 Billboard’s review of the new program noted that Benny’s nonchalant style of humor and delivery was different from what other comics were offering on air. “A taste for his style has to be acquired,” cautioned the reviewer, who also noticed the reliance on old vaudeville patter—“On this particular program he rang in some of his old material, but no doubt new to radio fans.”39

Years later, Jack Benny confessed his panic: “In vaudeville you had one show and that was it. You changed it whenever you felt like it. And in this, when you realized that every week you needed a new show, this got a little bit frightening.”40 In another interview, he recalled: “I didn’t have any idea how important it was to have good material, and how hard it was to get. The first show was a cinch—I used about half of all the gags I knew. The second show consumed all the rest, and I faced the third absolutely dry.”41

Established performers appearing on the airwaves similarly expressed terror at the speed with which the live broadcasts to huge audiences consumed a career’s worth of material in just a few hours. “The scourge of the amusement field is radio,” warned Variety. “Radio is devouring too much music, eating up the stage too cannibalistically and burning out all talent too fast, so that it may undo itself about as rapidly as it made itself prominent in its relation to the masses.”42 Ed Wynn complained that “the gags used in four half-hour programs would provide enough material for a full-length Broadway play.”43 While Variety acknowledged that radio had made nationally known stars of niche performers like Wynn and Jack Pearl, as well as previous unknowns like Gosden and Correll, it cautioned:

The very biggest on the ether today soon become boresome simply because it’s not showmanly to dish up a new act 52 times a year. Comics used to be able to test out their new routines in smaller towns like Plainfield and Union City, now can kill their careers with a bad routine in front of 20 to 50 million listeners in one night.44

Performers and program producers struggled to adapt old business models to this new mode of communication. The radio networks had consolidated the breadth of the vaudeville system into just a few broadcast outlets to serve a nationwide audience. The networks demanded that broadcasts be live each week. Program producers could not use previously recorded performances or reruns, options that might have made the search for fresh material, the pressure to perform at peak ability, and the chase for high ratings less fearsome.

During his years in vaudeville, Benny had regularly enhanced his routine by purchasing jokes and routines from gag writers such as Al Boasberg, Dave Freedman, Sid Silvers, and Harry Conn.45 He turned to them now.46 In the 1920s, Burns and Allen had paid Boasberg a continuous 10 percent of their $1,750 weekly vaudeville salary in exchange for his creation of individual routines, such as “Lamb Chops,” which they performed for years. The duo asked him to write material for their weekly radio broadcasts on the Robert Burns Cigar Program, but Boasberg balked at how much more work was involved in creating the seven to eight minutes of new material they required each week, for only 10 percent of their $1,000 radio salary. Boasberg quit and moved to Hollywood to take film-writing jobs.47 Burns and Allen and their radio producers soon assembled a staff of five writers to churn out all the necessary material. Dave Freedman devised an alternate method to address radio comics’ endless need for material (Eddie Cantor was one of his major clients). Freedman hired a staff of young assistants who combed through every source of humor in the library—joke books, magazine articles, and nineteenth-century literature—to cull every possible jest, quip, and comic exchange. They organized these jokes into vast files on every conceivable topic that Freedman could then dip into, rearrange a few particulars, and assemble into scripts churned out for a half-dozen different radio comedy shows each week.48

By the end of the second week, Benny sought out Harry Conn, a tap-dancing former vaudevillian who had turned to full-time writing, penning routines for dozens of comedians and for Mae West’s Broadway shows in the 1920s.49 In the spring of 1932, Conn was working on the Burns and Allen staff. Benny decided to rely solely on Conn, paying Conn’s salary out of his own pocket. The two quickly became partners, working closely together week in and out to create, edit, and perfect the dialogue. To Conn’s chagrin, the radio network would not allow writers to get on-air credit, however, so Benny always remained the focus of public and critical acclaim.50 Benny was as financially generous with Conn as he was dependent on him, paying Conn one of the highest salaries earned by a radio writer.51

By the end of the third week on the air, with Conn on board, the Canada Dry Program scripts started to become more adventurous. George Olsen now was given more straight lines as he and Benny engaged in conversation. Everyone else in the studio—from orchestra members and Conn to Benny’s personal assistant Harry Baldwin—was pulled to the mike to voice fictional guests in brief one-time appearances. Benny and Conn began experimenting with creating a richer fictional world for the program, creating sketch routines that briefly moved away from the microphone. On May 23, 1932, they finessed the problem of segueing by endowing announcer Ed Thorgerson with a magical ability to tune an on-air radio into conversation made by the characters at a soda fountain located in the building’s lobby. At midshow, Thorgerson asked where Jack was, and band member Bob Rice responded that he’d just left:

ED: but who’s going to take charge of the program?

BOB: I don’t know.

ED: I think I’ll tune in the soda fountain and see what’s going on there. (ad lib tuning noises, and FADE OUT)

(FADE IN: Scene at soda fountain. Sound effects: clink of glasses, fizzes of charged water, babble of voices requesting drinks, etc.)

ALLEN: And I’ll have a chocolate malted milk.

ETHEL: Make mine a made to order Canada Dry.

FRAN: There you are—and what will you have, sir? (band member Fran Frey played the soda jerk)

JACK: Give me two nickels—I want to telephone.

FRAN: Say, this is a soda fountain.

JACK: I’ll have a glass of Canada Dry Ginger Ale, made to order, by the glass at all soda fountains.

FRAN: Do you know the chorus, Mister?

JACK: Oh I see—now just give me a glass of Canada Dry.

FRAN: Would you like a little flavor in it, sir, say, a little cherry?

JACK: No—no—just plain Canada Dry.

FRAN: How about putting some ice cream in it? It’s swell with ice cream.

JACK: Yes, I imagine it is very good. But if you don’t mind, I’ll have just the plain Canada Dry—see?

FRAN: Would you like toast with it?

JACK: NO!! Say, were you ever a barber?

FRAN: Who wants to know?

JACK: Jack Benny

FRAN: Are YOU Jack Benny?

JACK: Yes—yes.

FRAN: The Jack Benny who broadcasts for Canada Dry?

JACK: Yes.

FRAN: Every Monday and Wednesday?

JACK: Yes.

FRAN: And if you ask ME if I was ever a barber. Gee THAT’s hot.

JACK: Will you please give me a glass of—(Ethel enters and interrupts)

ETHEL: Oh Jack!

JACK: Hello, Ethel.

ETHEL: You’d better hurry back. George is getting ready to play a number.

JACK: Come on, let’s have a drink first.

ETHEL: No thanks, I don’t want . . .

JACK: Come on, Ethel—I’ll pay for mine. (Ethel laughs at this)

JACK: Aw, I’m only kiddin.’ Come on, Ethel, I’ll buy them. Hey! Give us two Canada Drys. And make mine large.

FRAN: Okay . . . say, do you want a piece of cake with it?

JACK: Come here—lean over a minute. (sound effect, crash of plate) And NOW give us two glasses of Canada Dry.

(sound effect: fizzes of charged water)

ETHEL: What’s he doing?

JACK: That’s the way you make it—first put just the right amount of syrup in—then add the charged water—and there you are! Well, here it is, Ethel—-good luck!

ETHEL AND BENNY: (singing) How Canada Dry I am . . . How Canada Dry I am . . . (both start to laugh)

(Fade In: piano music, opening bars of the song “Tender Child”)

ETHEL: What’s that?

JACK: Say, that’s George beginning to play the next number.

ETHEL: Gee, I’d better run back—I have to sing it with Fran.

The show staff created sound effects of glasses clinking and ginger ale fizzing. The scene may have only lasted two minutes, but when Benny “returned” to the studio after the next song, he jokingly assumed that he had to explain to the audience what they had done: “Well folks, this is Jack Benny back at the studio. Well, to tell you the truth, we never even left here. Olsen’s bass drum was the counter. And the fizz you heard was one of the boys sneezing.”

Subsequent episodes contained a three- to five-minute sketch occurring in a fictional place away from the immediacy of the studio space. Some involved Jack traveling to a special event and reporting on it (essentially performing a monologue). Jack “attended” the Dempsey-Sharkey prize fight at Madison Square Garden, and parodied radio sports coverage, giving play-by-play action. Another time, Jack and George Olsen were arrested for speeding and broadcast the program from jail, and on July 6 the cast visited the zoo and gathered testimonials from the animals about how much they enjoyed drinking Canada Dry. Meanwhile, Jack continued to rib George Olsen about being a spendthrift. Back at the soda fountain, George offered to treat Jack to a glass of ginger ale, but had forgotten his wallet, so Jack ended up picking up the check for the entire orchestra’s order.

A PERIOD OF EXPERIMENTATION WITH

TOPICS AND CHARACTERS

Benny and Conn strove to avoid a rigid formula in constructing the radio program’s humorous segments, devising a mixture of comic monologues, repartee, pun tossing, and fictional adventures between the musical numbers. Some of their experimental ideas were solidly successful, while some were problematic and abandoned as unworkable. Others ended perhaps at the behest of their sponsor. Topical humor that satirized current radio programming fads was one of their first experiments. On May 9, Jack announced the beginning of a write-in contest, in which listeners would submit testimonials to the deliciousness of Canada Dry Ginger Ale. Benny’s radio show was followed by a musical program for San Felipe cigars, which was then currently conducting a jingle-writing competition with prizes valued at $70,000. Advertising agencies who created the radio programming loved these contests, for they generated thousands of listener responses that agencies could use to demonstrate the radio program’s popularity and justify the hefty expense of radio sponsorship to their clients. The Federal Radio Commission and NBC worked to eliminate contests, however, as they added a tawdry, hucksterish element to a network broadcasting that was trying to seem more culturally elevated.52 Benny’s increasingly absurd contest rules exposed the crassness of these gimmicks and made his sponsor seem insincere and foolish.53 Radio reviewers praised Benny for his clever parodies, calling them a delightful new twist in radio humor.54 On May 11, Benny announced his latest contest wrinkle:

Walk up to your favorite soda fountain, order a glass of Canada Dry Ginger Ale made to order by the glass and sip it through a straw—of course this is optional. You can either sip it through a straw or drink it right out loud. But if you DO happen to sip it through a straw, save it. Don’t go a losin’ it. Why? Send it to your Canada Dry cleaners to be pressed. Then, on one side of the straw write us why you like Canada Dry made to order by the glass, and on the other side, write the “Star Spangled Banner.” Mail your straws to us at your earliest convenience, as the straw hat season opens next week. We will not tell you what the prize is yet, but keep a scallion in mind.55

In the first months of the program, Benny and Conn dipped a toe into political satire. The upcoming presidential election must have been a topic difficult for radio jokesters to avoid, as the candidates’ sloganeering filled the newspapers. Conn and Benny brought a touch of cynical humor and an absurdity to their political skits, weaving Roosevelt and Hoover’s names into Benny’s monologues similarly to the way they talked about Clark Gable and Greta Garbo. In early June, Benny made a mild joke about ex-servicemen descending on Washington in the Bonus March, and at least one newspaper critic took him to task for making fun of a serious subject.56 On June 20, at midshow, Benny announced, “Ladies and gentlemen, we have been singing and joking tonight, but we realize our mistake, your minds are at present concentrated on the political situation. What you want is politics, not hokum, so politics you’ll get.” After a barrage of digressive jokes and puns, and a song (Olsen’s band performed a tune entitled “Everything’s’ Going to be Okay, America”), Benny introduced “The Canada Dry candidate for president, Trafalgar Bee-Fuddle . . . The man who broke his umbrella and is neither wet nor dry. He is a friend of the farmer, and is also a friend of the traveling salesman and the farmer’s daughter. He is a soldier, a scholar and a citizen, and has proved his worth at Leavenworth.”

BEE FUDDLE—(between bouts of coughing) If I am nominated at this convention for the highest honor that can ever be bestowed up on an American Citizen, I will . . . erm, I will . . . that is, er . . . er . . . I will be FOR the people . . . BY the people, OF the people . . . WITH the people . . . ON the people . . . and IN SPITE of the people. . . .

[Bee-Fuddle’s hysteria escalates, and then a pistol shot was heard, followed by silence]

JACK—Ladies and gentlemen, there is nothing to worry about . . . the LATE Trafalgar Bee-Fuddle will not run for President, but no matter who’s elected, Canada Dry Ginger Ale will be sold by the glass, at all soda fountains, TO the people . . . BY the people . . . and FOR the people. And it’s darned good . . . several people told me.

On October 19, Jack performed one of his prize fighting play-by-play monologues, this time a bout between “Battling Herbert Hoover and Fighting Franklin Roosevelt”

Hoover has trained faithfully in Washington, skipping the rope, balancing the budget, and doing some roadwork in Iowa and Cleveland . . . Roosevelt has trained in Albany and has done his roadwork in eighteen different states. We haven’t seen a fight like this in four years. . . . (gong) They both meet in the center of the ring. Hoover steps in with a light Rhode Island . . . and Roosevelt counters with a hard Smash-achusetts to the jaw. Herbert comes back and flings a Michigan, and Franklin blocks with Oregon. . . . They are now both throwing Iowas at each other. . . . So far it is a pretty even fight. There they go, dancing around, taking their time, but looking for an opening. Ah, Franklin now comes in and hooks a light Delaware to the ear. Herb now counters with a Nebraska, and Frank drops one knee to the Kansas, I mean canvas . . . and is up again from the Floor-ida . . . brushing off his pants-sylvania (Gong) and the bell sends them both to their corners.

Benny and Conn also experimented in those first months on the radio with ways to add additional voices. On May 25, Benny interviewed the janitor of the building, Mr. Philander Kvetch, played by band member Bobby Moore, who only responded to questions in gurgles of baby talk. On June 1, Kvetch briefly returned, speaking in a heavy German accent. This time the part was probably played by Harry Conn. On June 15, Conn was an Italian-American tough guy attending the boxing match. On July 13, Jack talked to a group of Scottish gentlemen who would be judging the latest Canada Dry contest; all the Scots were played by Conn (including a Scottish terrier who simply woofed). Ethnic characters were a favorite staple in Conn’s bag of comedy writing tricks; although use of foreign accents was a creaky throwback to earlier vaudeville days of Gallagher and Sheen, or an insensitive burlesquing of immigrants, it’s probable that Conn saw the ethnic-accented caricature of American voices to be a bit of “verbal slapstick” or unexpected aural comedy costuming for the airwaves. Despite Conn’s favoring of ethnic voices, he rarely appeared on-air as a performer again. The Benny show instead hired a range of ex-vaudeville comics as “dialect specialists” to play occasional small parts.

In the show’s second month, Jack began to talk about hiring an assistant to handle all the mail the program was receiving in response to the outrageous Canada Dry contests. This search continued over the next month, as Jack acquired first an inefficient male secretary, then an incompetent female secretary named Garbo.57 The next chapter details how Benny’s wife Sadye Marks Benny (his sometime assistant on the vaudeville stage) became incorporated into the radio program, as a young woman named “Mary Livingstone,” a fan of the program from the small town of Plainfield, New Jersey. She assumed the role of Jack’s lackadaisical part-time secretary on the radio show, and soon became a central character.

Along with adding Mary to the show came Benny and Conn’s brief experiment with a serialized narrative. Several comic radio shows had ongoing plots for their characters. Amos ’n’ Andy had a fifteen-minute comic-melodramatic plot that played out five nights per week. Eddie Cantor had experimented with a fictional narrative on his show (with mixed results, a few critics complaining about too much plot). Fred Allen placed his character into a constantly changing series of situations (running a night court, operating a department store) which introduced new characters every episode. Ed Wynn parodied opera librettos, a different one each time.58 Conn and Benny aimed for a continual mixture of different show formats—a situation or sketch one week, a parody of a film or standing around the microphone another. Still, the pair toyed with a romantic comedy subplot. Episodes in September and October 1932 played out Jack and Mary’s flirtations and comic misunderstandings, and climaxed with a scene of them espousing their love for one another. Benny and Conn had written themselves into a corner. Would the show now be dominated by a love story? Where would the comic conflicts arise? They quickly decided to move in another direction, however, backing away from romantic complications, or a continuing plot. Mary returned to flirting with the bandmates and ribbing Jack’s small foibles.

SPONSOR UPHEAVALS AND COMEDY POLISHING

After several months of twice-a-week programs, Benny and Conn began to garner critical notice for their experimentations with advertising and comedy situations. Variety reported in August, “Jack Benny was in good form on last week’s program, having evolved sundry effective gags for plugging Canada Dry. In line with the recent trend toward a humorous plug for the sponsor, he is sugar-coating and making palatable what is usually a boresome interlude in the best of programs.”59 In October, it commented, “Jack Benny is improving on his Canada Dry humor. Benny has built up a unique style of comedy, especially with those puns which, however, are not injudiciously primed for strong returns.”60

Just when Benny and Conn thought they had achieved a solid, successful mixture of comedy and music, with distinct characters, situations and parody sketches, their program was upended. In October 1932 Canada Dry and its ad agency abruptly declared their displeasure with many aspects of the program.61 N. W. Ayer & Sons found what it considered to be a more propitious broadcasting time at CBS, where a larger number of stations (27) were available to carry the half-hour program, on Thursdays at 8:15 P.M. and Sundays at 10:00 P.M. However, Benny’s bandleader George Olsen, his orchestra, and Ethel Shutta were all under contract to NBC and couldn’t move. The sponsor and ad agency and new network also changed the intimate set-up of Benny’s rooftop recording studio into a broadcast performance emanating from a cavernous stage before a large studio audience. Even worse, they hired an additional actor/writer (Sid Silvers) to improve what they thought was Benny’s flat comedy.

Benny and George Olsen stormed into Bertha Brainard’s office at NBC on October 7.62 Brainard reported that “Mr. Benny expressed himself as decidedly unhappy and uncertain about the future success of the program.” He objected to the change in orchestras, the additional writers, different broadcast set up. Benny certainly did not want Silvers added to the program, but his lawyer had informed him that he had to give it a chance. The lawyer also reminded him of the cancellation clause he could toss at the sponsor, if need be. Brainard continued,

I told Mr. Benny and Mr. Olsen how very unhappy we were at the loss of such a splendid program, which was building weekly, and that the feeling was that it was a gamble as to its popularity when Mr. Olsen left the program. Mr. Olsen told Mr. Benny that if anything should come up which left Mr. Benny free, we at the NBC would no doubt agree to combining the Benny-Olsen combination again, and continuing it on the air perhaps sustaining, if a client were not immediately available. Mr. Benny left saying that he was glad to know the door was wide open, and that we gave him a much clearer picture of how he might proceed. His statement was “Now I can use a black-jack,” meaning, I assume that unless things are decidedly as he wants them, he will give his notice, and offer his services to NBC.63

Benny and Conn were saddled with Sid Silvers and had to start over from scratch—teaching a new bandleader, singer, and announcer how to become comedians, and fighting off the intrusions of Silvers, who turned the show into the continuing story of a befuddled Broadway producer and his smart-aleck assistant (played by Sid). Silvers filled the scripts with zippy one liners instead of dialogue, made himself a comic equal to Jack, and left little room for Mary. There were no more parodies of movies or informal real-life exchanges around the microphone, and the Canada Dry ads were much less integrated.64 Although Benny, Conn, and Livingstone held no personal animus against Silvers (they would work with him in later years in film and Friars Club performances), within a few weeks the three staged a showdown with the sponsor, demanding that Silvers be removed and creative control of the program be returned to them, or they would quit.

By December 8, Benny, Livingstone, and Conn emerged victorious from the debacle. Sid Silvers was gone and the show returned to its previous style. In his opening monologue, Jack welcomed listeners back: “You know, I tell a joke and Ted Weems plays, I tell a joke and Andrea Marsh sings and I tell another joke and you laugh, and if you don’t I hear about it.” Although critics had praised him, one writing that Benny’s “air appearance [has] brought forward much of the present style of radio humor,”65 exasperated Canada Dry executives judged radio sponsorship too troublesome, cancelled Benny’s show in January 1933, and withdrew from broadcast advertising.

Jack Benny went through a stressful period as the producer and star of his comedy program over the next twenty-four months, as he was picked up and dropped by several sponsors. The story of his management struggles is told in chapter 6. Despite the many challenges of persevering through changes in cast members, sponsors, advertising agencies, networks, and broadcast nights and times, Benny’s radio audiences followed him and stuck with him. The program’s steadily rising ratings were one indication that Benny and Harry Conn had developed a winning comedy formula, drawing from the strong framework they had created in 1932. When the program returned to the air, sponsored by the Chevrolet automobile manufacturing company in March 1933, Jack was the program’s acknowledged main focus, and it was billed as a comedy program that contained music. Mary assumed a much more prominent role on the program as Jack’s companion, the only female character on the show, and the program’s main “stooge.”

Political humor played a significant part in episodes that month, as Benny and his troupe joked regularly about Franklin D. Roosevelt’s inauguration, the bank holiday, and other aspects of the New Deal initiatives Roosevelt rolled out in his first hundred days. On March 17, while doing his radio columnist skit as “The Earth Galloper,” Jack announced that banks were reopening, three of them in Hollywood (Tallulah Bankhead, Douglas Fairbanks, and George Bancroft).66 In another episode, Mary compared Frances Perkins’s appointment to the cabinet with her own time spent in a steam (weight-reducing) cabinet. This all was the lightest kind of topical humor, neither supporting nor criticizing the New Deal, reducing political news to the foolishness with which they portrayed Hollywood celebrity gossip. But nevertheless, by the end of their first month broadcasting for Chevrolet, every reference to politics was removed from the program. Given Chevrolet’s financial difficulties, its problems with labor unrest, and its upcoming negotiations with Roosevelt’s National Recovery Administration, company executives and ad agency staff were probably very nervous about their sponsored radio show raising anyone’s hackles.

Critical acclaim for the show continued to grow. The Ottawa Citizen’s reviewer complimented Benny for the quality of humor he created with his cast of characters—“Jack has the knack of making everyone on his program real and human, instead of just a lot of radio voices.”67 That summer, when Chevrolet put the radio show on hiatus (retreating from national advertising when their revenues lagged so badly) Benny and Mary Livingstone returned to the stage in a personal appearance tour, and vaudeville critics remarked on Benny’s new level of radio-fueled stardom: “[His] popularity was never so frankly confessed by the public prior to his radio career. What the air did for Benny was to make him a household character,” a Chicago reviewer noted.68

By spring 1934, despite the continuing turmoil of changing cast and broadcast times, and rancorous relationships with sponsors, the humorous content of the Benny show remained rich; the show’s narrative formula and characterizations were evolving into the forms Benny would rely on for the rest of his career. Harry Conn concentrated even further on developing the personas of the cast’s other performers as quirky, individual characters. Bandleader Don Bestor was a highbrow; tenor Frank Parker was a sophisticated young smart aleck. Mary was boisterous but not very bright. Jack was making fewer of the jokes, and more often it was the stooges who got the laugh lines, by ribbing Benny.69 More than ever, Benny became the poor “shmo,” the unlucky fellow to whom humiliating things always seemed to happen.70 On the May 11, 1934, show, to make a peace offering after they’d had an argument at the show’s opening, Don Wilson invited Jack out to his mother’s home in the Bronx for the weekend. Jack suffered numerous misadventures on their journey, getting robbed three times and gladly handing over his money in each instance. The thief even awarded Benny a card identifying him as a frequent customer. When the pair finally arrived at the Wilson home, there was no food, no spare bed, and no luck for the hapless Jack.

Benny’s character began to shift further from being just the likeable, self-deprecating but professional emcee of the program to develop more personality quirks and flaws (cheapness, boastfulness, his poor violin-playing skills, his vanity, his advancing age, and his lack of masculinity). The list steadily grew longer as the Jack character lost most of that assured “Broadway Romeo” suavity he’d demonstrated during his vaudeville career, and was now depicted as inept at interacting with the opposite sex. His patriarchal authority as star of the show was more frequently challenged by his mocking radio employees. While standard joke book-style insults about cheapness and stupidity were still bandied about by the entire cast, the jabs were refurbished so that charges were now often made by others, egged on by Mary, and aimed at Jack.

A significant turning point for the Benny character occurred in a skit about Jack’s Hollywood screen test, on the June 8, 1934, program. Benny had taken his radio cast out to California, as he was appearing in Transatlantic Merry Go Round, a film about criminal intrigue set on an ocean liner, produced by Edward Small at RKO. As Benny had done since the beginning of his radio show, he entwined references to his moviemaking work and personal details of his life into his scripts, blurring the lines between fictional and real Jack Benny personas. Conn and Benny drew on his self-deprecating traits and pushed them further, now enacting professional incompetence. Conn created a skit in which Jack was at the film studio, where he has been compelled to submit to a screen test to secure the role of romantic leading man. As scripted, Mr. Kane the director was trying to complete the test, and a nervous Benny was making that difficult:

KANE: Now for the first line, say “Ah Christina, your royal highness, thou are ravishing this evening, Would’st that thou favor me with thy presence at luncheon forthwith!”

JACK: I’ve been waiting for a Jimmy Cagney part like this.

[Jack’s first stumbling attempt to read his line is, “Oh, Christina. . . . er . . . er . . . ah Christina . . . er . . . er . . . can you cash a check?]

KANE: Now Mr. Benny, I think we better rehearse this first. . . . you walk up to Miss Hill and say “Christina, I love you.”

JACK: I see, OK. [SFX heavy clomp of footsteps]

KANE: Not so heavy on the walk!

[Don Wilson the announcer interjects a reference to sponsor General Tire]

DON: Jack, I think he means the Silent Safety Tread!

JACK: You would, Don. . . .

KANE: Yes, that’s it. Now come on, read your line.

JACK: All right . . . [very flatly].Christina, I love you.

KANE: How do you expect her to believe that? Come on, put some passion into it . . . try it again.

JACK: Christina, I love you!!!! [pants] . . . How’s that, Mary?

MARY: I still like Robert Montgomery.

KANE: Aw, a little more fire now. . . . Ask Christina for her hand in marriage.

JACK: Will you marry me?

BEVERLY HILL: I should say not!

JACK: Now what do I do?

KANE: Register surprise!

JACK: Why Christina, I’m surprised at you!

BEVERLY HILL: I never want to see you again!

KANE: Register grief!

JACK: Gee whiz, gee whiz. . . .

KANE: For heaven’s sake, is that grief?

JACK: That’s grief where I come from.

KANE: Where do you come from?

JACK: Waukegan.

KANE: That IS grief!

JACK: Oh yeah? Cut!

KANE: Wait a minute, that’s my line . . . cut!

The scene devolved into further humiliation for Jack as the director called Don Wilson over to demonstrate appropriately virile histrionic skills. Wilson passionately extolled the virtues of General Tire’s blowout-proof tires to the heroine, while Jack fumed on the sidelines.

After another sponsor switch, to General Foods’ Jell-O product, and several worrisome months of low product sales, the stars of both the business and humor sides of the production aligned for Benny in late 1934. His sponsor was happy, and Benny’s program topped the ratings charts. Journalist O. O. McIntyre lauded the show: “Benny’s humor has the dry crackle of sun-burned twigs. Never explosive, he bungles along, firing the arrows of contempt at himself. He brought to the business of being a comic a combined restraint, a suavity that was something entirely different, and it clicked.”71 Radio Guide agreed, noting: “Comedian Benny learned long ago that the way to make people laugh without straining is to create a comical situation—not to redress old jokes in party clothes and rely on studio applause to get them over. Jack also learned that the public loves to see the headman made the fall guy.”72

THE TROUBLE WITH HARRY CONN

As the fall 1935 radio season opened, the collaboration between Jack Benny and Harry Conn appeared to be golden—the show was ranked number one in the ratings, and accolades showered down upon the pair. They were considered the closest creative team of performers and writers on the air after Don Quinn and Jim Jordan of Fibber McGee and Molly and Gosden and Correll of Amos ’n’ Andy.73 Variety’s review of the Jell-O Program in late September was lavish in its praise of the show’s writing and performance:

Harry Conn, who authors this program, seemingly has struck upon the happiest formula yet found for commercial comedy on the air. . . . Conn’s method is to first establish his characters, then build his laugh directly through or with the character itself. . . . Where Conn also shines is in the blending of his writing style with the delivery of Jack Benny. No better example of perfect actor-writer mating is to be found in show business. Conn writes the way Benny talks, and vice versa.74

Strain between the collaborators began building, however, due in no small part to the constant effort it took the two to keep their popular show on the air. An indignant Harry Conn saw Jack Benny reap all benefits and salary of stardom, while Conn labored behind the scenes. Scriptwriters for all major radio programs were frustrated by their meager status. A 1935 Variety story asserted, “Writers 2% of Budget; Sponsors rate scribes low.”75 NBC until very recently had refused to give writers on-air credit for their work, Variety reported, the network claiming that sponsors did not want precious airtime given over to lengthy film-like credit sequences. Screenwriters in Hollywood earned salaries equal to about 10–15 percent of the budgets of pictures they were contracted to write. Radio writers, on the other hand, earned a pittance, often only between $50–200 per week for a show that cost thousands of dollars. Conn was the highest-paid writer in radio, the article acknowledged. Now Harry Conn’s ego swelled while his resentment grew. He enmeshed Benny in an increasingly bitter struggle over the question of who was responsible for the radio program’s success—was it Conn’s authorship of the script or Benny’s sense of timing and performance?

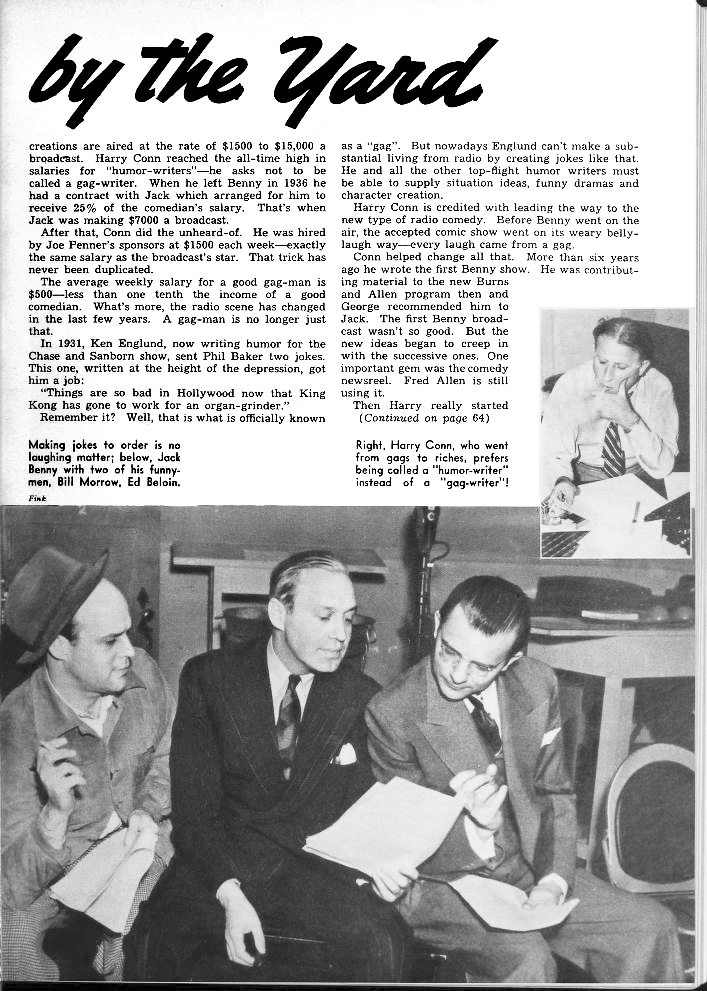

FIGURE 4. Fan magazine Radio Mirror shows Jack Benny working closely with his current young script writers, Bill Morrow and Ed Beloin, while former Benny show writer Harry Conn is depicted working solo, more important than the comics he supplied with dialog. Radio Mirror, November 1938, 41. Author’s collection.

While Jack Benny rarely detailed his creative input into the radio program, his contributions to the show’s writing and production were enormous. Benny’s role was far more than just a dialogue reader. While Benny acknowledged that he was no ad-libber, and that he was not quick to invent a steady stream of comic situations or one liners to fill the weekly scripts, he was a superb editor of comic dialogue. He possessed a keen sense of language, rhythm, and timing, and he constantly tinkered with scripted lines for himself and the cast right up until the moment of live broadcast. He condensed and sharpened the jokes, their build-up and responses, eliminating unnecessary words and polishing the lines as if they were song lyrics to compliment a tune. Benny’s other major contribution was in the performance of the script. He was brilliant at adding emotional and comic emphasis to line readings with his tremendous sense of timing, and he could coach it out of other performers and nonprofessionals. Benny conducted his rehearsals and broadcasts like a symphony maestro without a baton—with looks, nods, and fingers pointed at the performers to key their lines and to direct the sound effects engineers.

Harry Conn considered himself the creative force of the radio program, the person who invented the original characters, skits, and dialogue for the show. He gave little credit to that alchemy of talent and public appeal that made Jack Benny a star. In 1935, Conn began a public relations campaign in newspapers and magazines, giving interviews about his contributions to the Jell-O Program, reframing the group project to emphasize his lead role as writer and insinuating that Benny and his cast merely read his scripts.76 One story, published in the Los Angeles Times,77 was accompanied with a large photo of Conn perched confidently at the typewriter, and Benny looking on from behind like an underling. Another in the Boston Globe78 featured “Sad Faced Harry Conn, Radio’s Little Known Mogul of Mirth”: “Radio’s no.1 wit is a man who has never appeared before the microphone. . . . Meet Harry W. Conn, Jack Benny’s ghost writer. . . .” Conn was famously known to joke about Benny’s lack of spontaneous creative ability, claiming that “Jack Benny couldn’t ad lib a belch after a Hungarian dinner.”79 His flippant pronouncements about Mary Livingstone’s acting skills also danced on the edge of being insults. “Conn calls Mary Livingstone (Mrs. Benny) an ‘indifferent comedienne’” one interview noted, continuing, “He has written a Mother’s Day poem for her to intone today. ‘I don’t care how I write them,’ he said, ‘and she doesn’t care how she reads them. So between us, we get a laugh.’”

For the Fall 1935 season, Conn demanded a significantly larger share of the Benny empire—not only a doubled weekly radio salary (from $750 raised to $1,400), and extra money for polishing the dialogue in Benny’s films ($1,200 per week when they worked at MGM), but also 5 percent of the income earned from Benny’s live stage show appearances, and 5 percent of Benny’s film earnings. Conn further demanded a royalty of 5 percent of Benny’s subsequent radio earnings for five years after the contract, whenever Conn’s material was used. Benny’s later manager, Irving Fein, recalled that this contract (to which Benny acquiesced) made Conn feel only more entitled, and provoked even more rude and arrogant behavior. “One incident which helped bring much friction to the surface occurred when Mary Benny came in one day with her first mink coat, and Harry Conn’s wife said ‘If not for my husband, you wouldn’t be wearing that mink coat.’” Benny must have felt increasingly squeezed between his dependence on Conn to continue to provide the material that made their program a hit, and frustration with a partner seeming to overstep his bounds. A more cynical performer might have brought in additional writers to spread the responsibility and maintain managerial control; but Benny was loyal to his tight circle of friends and business associates.

Perhaps these behind-the-mike tensions impacted the quality of the Jell-O Program, for in early 1936, radio critics began finding fault with the show. Larry Wolters of the Chicago Tribune claimed that the scripts had grown considerably weaker, laying the problems to continuing cast turnover (popular tenor Frank Parker left and several band leaders had come and gone).80 Benny acknowledged only that “his scriptwriter had a barren period” and Wolters added, “Jack admitted that criticism of his efforts this year has been widespread and he is bending every effort to restore the old sparkle of his program.”81

Amid this turmoil, Benny, Conn, and the radio cast embarked from Los Angeles in February 1936 on a grueling twelve-week road tour, making personal appearances at theaters across the Midwest and East, while performing the Jell-O Program each Sunday. Conn had fallen back into the habit of relying on ethnic dialect to provide the humor in many of the program’s sketches, disguising a lack of witty dialogue with unexpected voices. One week the cast performed a Northwest Mounted Police sketch that involved Greek and Irish characters played by dialect comic Benny Rubin. Another week, it was a zoo tour in which cast members encountered zookeepers played in Jewish and Irish accents. Other skits, however, such as Jack, Don, Mary, and Kenny switching roles and personalities to break up the monotony of the program opener, were sharp. The frustrations of travel added to the general show malaise. In Cleveland, Jack became so ill that the group had to cancel its week’s appearance onstage. In March, the Benny troupe bounced between Pittsburgh; New York; Washington, DC; and Baltimore.

As Benny placed an acknowledgement in Variety of winning the New York World Telegraph’s popularity poll for the second consecutive year, Conn countered with a boastful announcement, printed on the same page:82

Writer of First Run Material

HARRY W. CONN

Now Serving fourth year writing the radio programs for

Jack (indifferent) Benny and

Mary (careless) Livingstone

And My public, please forgive me

I’m responsible for writing Mary’s Poems

And also

“The Chicken Sisters”

Fifteen minutes of Torso Vibrating Laughs

Now appearing in Mr. Benny’s State show

State, NY, this week (March 6)

Fox, Washington, next week (March 13)

Written by HARRY W. CONN Staged by JACK BENNY

Benny said nothing publically about Conn’s presumptuousness. March was contract renewal time for the next broadcast year, and Conn chose this moment to make his most daring demand yet, presenting Benny with his contract requirements, as the Benny troupe pulled into Baltimore for a week of shows at the Loew’s Century Theater. Conn requested a 50 percent share of Benny’s salary. “Jack told him that it was ridiculous and refused to discuss such a contract,” recalled Irving Fein. “Jack was ready to give him a handsome raise, but Conn refused. . . .”83 Holding firm in his demands, Harry Conn and his wife immediately disappeared.

As it became later and later in the week, Jack Benny fumed in his Baltimore hotel room between stage appearances, with no Conn-provided script for Sunday’s live radio broadcast in his hands. Finally, Benny was forced to plunge in and hurriedly write a script. He called his friend, radio comic Phil Baker, who lent him two writers, Sam Perrin and Arthur Phillips.84 Benny’s vaudeville friends Jesse Block and Eve Sully attended the Baltimore broadcast and came up from the audience to join Jack and Mary on stage. Benny resurrected one of the program’s oldest melodrama parodies from 1932, “Why Nell Left Home.”85 While the episode was not spectacular, it was adequate.

Late the following Tuesday night, with still no word from Conn (who had decamped to Atlantic City and then to Miami), Benny’s frustration poured out in a torrent of words in a four-page telegram, sent to Conn at his Miami hotel. The telegram’s text reveals a rare example of Benny at his most emotional. It is also one of the few times he detailed the labor he put into the production of his program.86 After rebutting Conn’s complaints that Benny did not publically acknowledge the writer’s contributions to the program, Benny dismissed Conn’s assertions that Benny’s fame was completely the product of Conn’s scriptwriting:

You have also told many people, including my father, that you made me the star that I am today. That is fine talk, particularly to my father. You cannot make me a star or anybody else in show business—all you can do is help and that is what you have been getting paid for. I am not the only star in show business. Phil Baker is a star, Freddie Allen is a star, Burns and Allen are stars, Eddie Cantor is a star, and you have never written for them. I have paid you more money than any two authors would get from an actor all out of proportion to my radio salary. Every move I have made, whether it is pictures, stage or radio, you were included. Can you name one radio writer whom the public knows as well as they know you. As far as making me a star is concerned, I was a star long before you and I ever became associated. While I am on the subject, let me mention the very latest ad you took out in Variety two weeks ago which at least twenty people have mentioned to me as being most humiliating and in the worst of taste. In your future ads please state that you are writing the Jell-O program and leave the names of Jack Benny and Mary Livingstone out of them.

Finally, Benny made a case for the importance of his own authorial contributions to show scripts, and ultimately drew the line between performer and employee:

I have sat up for hours, constructing, editing and helping on all material for which I have never taken the credit. . . . This past season has been the most miserable I have ever spent in show business. I have given you every protection an author could possibly get insofar as writing—no matter what the expense.

After the expiration of this present radio contract you are free to do as you please, as I do not think that either of us could stand the strain longer. However, as this contract with me has 13 more weeks to go, I would like to have the scripts as per our contract, delivered to me not later than Thursday night of each week. From then on I will be glad to work on them alone. Everything contained in this wire has been on my mind and in my heart for the past year and I am glad it is out.

Scrambling to create episode scripts, once in New York, Benny called in favors from his friends to help secure writing talent—Goodman Ace contributed, along with gag writers Hugh Wedlock, Howard Snyder, and Al Boasberg. His producers at the Young & Rubicam agency, Tom Harrington and Pat Weaver, also pitched in.87 Benny got some of his confidence back in a lively, funny program on April 5. Fred Allen had offered Benny the use of one of his assistants, Ed Beloin. Beloin’s familiarity with Allen’s material may have generated the script idea, for the topic of Benny’s show was a parody of Allen’s Town Hall Tonight. The episode sparkled with wry humor, and its spot-on burlesque of Allen’s show presaged the Benny-Allen feud that would commence eight months later. Beloin, Bill Morrow, a young radio writer from Chicago, and the experienced Al Boasberg emerged as Benny’s new team of writers.88

Benny’s third show without Conn was nightmarishly difficult. He and the cast were back on the road in Cleveland to make up for the earlier missed stage appearances. Benny decided to proceed with an attempt at parodying Eugene O’Neill’s current hit Broadway drama Ah, Wilderness. Benny and Conn had garnered big publicity when they had asked O’Neill’s permission earlier in the year to do the take-off, as the author had turned down requests from several other comics. The script in Benny’s files shows many last-minute edits, deletions, additions in shorthand, and dialogue lines crossed out of the muddled skit. Right before the parody skit began, the audience heard a loud “click” sound, and when Benny asked “What was that noise?” Mary curtly replied, “O’Neill just turned his radio off.” After several more weeks of travel, the cast finally returned to Los Angeles in late May, to fine tune a new system of collaboration in the last four weeks of the broadcasting season.

Harry Conn was still under contract to Benny through the end of June. He submitted the required scripts in a desultory and often last-minute manner, along with providing (unwanted) advice on Benny’s management of performances on the Jell-O Program. Conn repeatedly remonstrated Benny for pacing the program too quickly. On June 9 he wrote Benny, “Last week’s show played very good, but I think you are letting your people run with lines. By doing that, they make you rush, and you are at your best in a slower tempo. I have mentioned this before and repeat it as I know I am right.”89 Perhaps this was the kind of give-and-take bantering they used to have as partners, but surely Benny did not wish to be addressed as the performer who knew less about both management and performing. Conn also provided several ideas for film parodies, which would have been challenging assignments for the new writers; comic twists on Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream sketch (based on the recent Warner Bros. adaptation); and the controversial Broadway drama The Children’s Hour. “Mary has to play her lines as the BRAT . . . and you will have to do a janitor with Strange Interlude cracks to be in it. Kenny [Baker] and [bandleader Johnny] Green [could] do a few of the girls as it is a seminary and you explain you’re short of girls. I think it’s a great bit if no one rushes, it needs a good rehearsal.”90 Benny and his new writers did not take him up on the suggestions. After a summer of rest, they created a rejuvenated Jell-O Program with more sparkling wit than the previous year, and rode back to the top of the ratings.

When Conn soon afterward secured a lucrative scriptwriting deal with the Ruthrauff and Ryan advertising agency, the news made the front page of Variety. Everyone in the radio industry wanted to see what the talented writer would do next. Conn landed a contract to write the scripts for veteran radio comic Joe Penner for the Cocomalt Program, earning $1,300 per week, as much as the fading star. Conn cheekily published an open letter to Benny in Variety, publicizing the end of their four-year association and patting himself on the back for “providing the material that kept the Jack Benny program up there on top for so long.”91

Just ten weeks into the Fall 1936 season, however, Cocomalt fired Conn.92 Variety noted with wry amusement that Conn’s replacement, Don Prindle, formerly a $40 per week scripter at a Seattle radio station, would now write Penner’s program for $250 a week.93 Conn’s downward slide was swift. In January 1937, Ruthrauff and Ryan placed Conn as a writer on Al Jolson’s radio show to build up a major role for actor Sid Silvers (the Canada Dry Program interloper in Fall 1932).94 But six weeks later, both Silvers and Conn were terminated.95

In November 1937, Harry Conn announced he was to write and star in his own comedy, Earaches of 1938, broadcast as a sustaining (unsponsored) program on CBS.96 The show was scheduled at a terrible time, opposite the popular Charlie McCarthy–Edgar Bergen program.97 The situation-comedy narrative that Conn devised was a copy of the Jell-O Program, with a group of zany characters (an emcee portrayed by Conn, exchanging insulting banter with a band leader, announcer, and some comic stooges), attempting to broadcast a radio program.98 Reviewers snidely noted Conn’s nervous performance, and faulted Conn for not creating a unique comic character for himself, yet admitted that the show had promise.99 Earaches did not succeed in securing a sponsor, however, and the program was cancelled after thirteen weeks.

In 1939, after burning his bridges in radio, Conn launched a lawsuit for breach of contract against Jack Benny, seeking $60,000 as his percentage of Benny’s ongoing earnings from use of material and characters drawn from Conn’s original radio scripts.100 The lawsuit spent a year in the courts until finally it was settled by an arbitration board. Benny paid Conn $10,000, and both retained the right to use material from the 226 scripts Conn wrote, although Benny was careful to insist that Conn couldn’t reuse entire episodes, mention Jell-O, or use any of the names of the characters he had originated (particularly, that of Mary Livingstone).101 Afterwards Conn faded into obscurity, and little is known about the rest of his career, other than that he had serious health problems and that he occasionally wrote to Benny to sell him comedy material or to borrow money. Conn was last spotted by New York newspaper columnist Dorothy Kilgallen in November 1958, working as a backstage doorman at Broadway’s Playhouse Theater, where Jack Benny was embarrassed to have accidentally encountered him.102

• • •

When the Jell-O Program returned to the air in October 1936, firmly anchored in Hollywood and with yet another new bandleader (Phil Harris), Jack Benny’s program solidified its place as the most popular comedy show on American radio. In the four years since his tentative start, vaudevillian Benny had learned a great deal about radio and conquered many of its particular challenges—from his fortuitous choice of writer Harry Conn through the pair’s experimentation and innovation in development of quirky, individual continuing characters, humor built not through stings of one line jokes but in a workplace-anchored situation comedy, and flippant commercials, to Benny and Conn’s development of Jack’s Fall Guy persona who was the butt of incessant insults and mishaps. Along the way, Benny and Conn briefly experimented with romantic plot devices and political humor, and they had struggled to gain creative control over the program’s format from meddling sponsors. They became radio’s brightest fun makers, until the pressures of production deadlines, creative spark, and public fame and fortune destroyed their partnership. Harry Conn deserves half the credit for turning Benny the vaudevillian into Jack Benny the radio star. Unfortunately, his ego and insecurities damaged his subsequent career and blunted his legacy. The fact that the vast majority of the radio episodes Benny and Conn created together from 1932 to 1936 have not been available to circulate in recorded form has prevented fans then and now from being able to assess their accomplishments. Now that efforts are being made to make the scripts and reenactments of these long-lost episodes public, this early period, which fans have considered the least important of Jack Benny’s radio career, will receive more appreciation for the sparkling comedy it produced and groundwork these shows laid for the future of Benny’s show.

Along with Benny and Harry Conn, the third pillar supporting the creativity and innovations of the Benny program’s early years was his wife, Sadye Marks Benny, popularly known as Mary Livingstone. The next chapter explores the evolution of Mary’s character and its development as the lynchpin of the success of Jack’s Fall Guy character. It also examines Sadye Marks’s reluctant journey along the way to becoming a prominent and influential (if now largely forgotten) radio star.