The Commercial Imperative

JACK BENNY, ADVERTISING, AND RADIO SPONSORS

“Jack’s success as a salesman in moving goods, first for General Foods and then American Tobacco, was absolutely incredible,”1 recalled legendary broadcasting executive Sylvester “Pat” Weaver in 1963. Weaver knew what he was talking about, having worked with Jack Benny in radio over twenty years through an advertising agency, a sponsor, and a network.2 Benny collected accolades from industry observers, critics, and the public throughout his radio career for his ability to merge entertainment and consumer product advertising. As soon as he started in radio, Benny learned that commercial broadcasting had a wider variety of masters to please than he had experienced in vaudeville or in film. Each group he worked with in radio promoted different agendas. Harried network vice presidents attempting to keep sponsors satisfied tried to shape Benny’s program. Persnickety sponsors interested in promoting their product and pleasing their own cultural tastes tried to dictate what Benny did on air. Advertising agencies sought to bend Benny’s radio show to their own marketing interests. To navigate this minefield, Benny became what the television industry today would term a “show runner”—not only a performer, but also an involved, hands-on co-creator and manager of his own entertainment product. Getting the support and resources he desired, and creating comedy in these circumstances was not easy. After all, Benny ran through four sponsors in his first two and a half years on the air.

Consumer advocate groups and radio critics bemoaned the commercial imperatives of radio in the 1930s and 1940s, despairing at the professional, aesthetic, and ethical compromises that program creators had to make for the sake of selling things.3 As no one was more successful than Benny at working within the context of advertising, he could easily be dismissed as a “sell out.” Given the industrial factors in the contemporary entertainment world pushing advertisers back into production of media content, however, there are lessons to be learned in analyzing how Benny negotiated, over nearly twenty-five years in radio, the complex relationships and restrictions of the sponsor system.

By involving himself in the creation of commercial advertising messages, Benny could enhance his radio program in several ways. He could have more control over the content of the twenty-seven minutes of his show that fell between the bookends of opening and closing commercials. This helped Benny shape the “flow” and continuity of his program. Especially as Benny and writer Harry Conn began developing characters and story lines (as opposed to presenting a collection of one-line jokes), the comedy benefitted from lack of the jarring interruptions of ad verbiage so common on other shows. Benny turned his radio announcer from the pompous, dour person who droned dull messages into a joke-making member of the radio family. Benny scripter Milt Josefberg recalled, “Jack’s kidding of the commercials became a high plateau of humor on his programs, and the public looked for it as eagerly as the rest of the show.”4

Crafting the middle commercial themselves also allowed Benny and his writers to do some ideological work on the sly, whether it was the mischievously subversive Canada Dry and Lucky Strike ads, or the more generally ironic attitude toward consumer culture woven into the ads for Chevrolet, General Tire, and Jell-O. Benny’s humorous commercials helped further break down the barriers between the production orientation of traditional American culture toward one that was more focused on consumption. Even if Benny’s character was unwilling to spend a dime, the commercials in his programs acknowledged that his radio audiences lived in a world of products that fulfilled needs and provided pleasures. The brands that Jack and his cast members mentioned so often on the air became familiar characters in listeners’ imaginations.

While previous accounts of Benny’s career have generally depicted Benny’s business dealings as congenial, in fact, Benny had to struggle repeatedly against sponsors’, advertising agencies’, and networks’ contrary wishes, irrational demands, and attempts to control his program; they tried to alter scripts and program themes, choose their own writers and performers, and constrained Benny’s efforts to pursue other entertainment endeavors. The dearth of surviving archival sources probably obscures many other disagreements that must have occurred between Benny and his bosses. This chapter charts Benny’s innovative advertising practices, and examines how Benny parried the interfering efforts of his bosses. It focuses on three case studies—the “wild frontier” of humorous Canada Dry advertising in 1932, the synergy of selling Jell-O using humorous “soft sell” tactics from 1934 to 1943, and Benny’s creative solutions to the challenge of working for the creator of the most obnoxious, irritant-inducing, hard sell advertising in all of radio—American Tobacco’s George Washington Hill.

THE UNCERTAIN ROLE OF HUMOR IN ADVERTISING

“Humor in advertising is greatly admired by creative advertising people, widely noticed and talked about by the public, and seldom used,” pronounced advertising executive Draper Daniels (a model for the TV series Mad Men’s Don Draper) in a 1959 guide for advertising copywriters. “Frustrated humorists in the advertising business frequently attempt to explain this seemingly contradictory set of circumstances by claiming that it seemingly proves that most advertising people on both the agency and client side of the fence are stuffed shirts.” Daniels continued,

When humor is used in advertising, it is too frequently dragged in in a manner that diverts attention from the product that is the advertisement’s sole excuse for being. The problem is to keep the sound of the customer’s laughter from drowning out the persuasive words of the sales talk. . . . Many people look upon the expenditure of money, particularly in large amounts, as something other than an occasion for laughter.5

Draper Daniels’s distrustful view of the use of humor in commercials had been widely shared by advertising executives across the first half of the twentieth century. Advertising historians Cynthia Meyers, Roland Marchand, and Stephen Fox have analyzed how the professionalization of the advertising business led earlier industry leaders Albert Lasker and Claude Hopkins in the 1910s to develop “scientific advertising” and an approach to ad copy called the “hard sell.” Hard sell advertising was serious; it provided as many factual “reasons why” an advertised product fulfilled a consumer’s needs as it would take to wear down the customer’s objections and leave them no choice but to buy.6 Hard sell advertising in print was direct, wordy, and obnoxiously insistent. In the early 1930s, agencies’ translation of hard sell advertising copy directly into scripts read out by radio announcers made those commercial announcements on the air sound even harsher to listeners’ ears.

Despite advertising leaders’ insistence that they knew the best way to sell the goods, other innovators considered the potential of humor and lightheartedness in print and radio ads. During the Depression, advertising agencies like Young and Rubicam (Y&R, Jack Benny’s agency in the Jell-O years) focused not on selling a product to a rational but uninformed customer, but instead on building long-term emotional relationships between products and customers, and creating brand identity and brand loyalty, in examples like the flippant tone of Postum ads, the comic strip characters it developed to sell Sanka Coffee, and the loveable Borden product symbol Elsie the Cow. “Soft sell” proponents crafted ad campaigns that tapped into psychological ties that bound consumers to products, and presented products as helpful friends that solved their problems, increased their self-confidence, brought them untold pleasures, and guaranteed their success in life. Humor was an emotion that could reduce audience resistance to the commercial messages. Even for soft sell advocates, however, comedy’s ability to help sell the goods was warily approached.7

“Humor in advertising is a dangerous weapon,” Daniels warned. “It is difficult to sell to your boss, difficult to sell to a client, and with reason. Nothing falls quite so flat as an attempt to be funny that fails.” The rewards of successful use of comedy in ads were tantalizing enough, however, Daniels reluctantly concluded, that talented and fearless copywriters could give it a try.8 Daniels praised the ten-year legacy of advertising accomplishments of Jack Benny and announcer Don Wilson for Y&R’s Jell-O program “with their integrated personality commercials and deceptively casual, good humored hard sell.” Daniels felt that, underneath the surface of soft sell comedy ads, their direct sales pitches worked as pointedly as “reason-why” ad copy of old.9 Daniels acknowledged the persuasive skills of talented announcers like Don Wilson and “the tremendous contrast with which his breezy, uninhibited approach stood out against the polished, bombastic advertisingese mouthed by the average radio announcer.”10

Pat Weaver (who had been one of those innovators at Y&R in the 1930s) argued that different products required different sales approaches. Some sponsors’ products benefitted tremendously from the development of relationships between an entertainer or mascot and the product, what Weaver called “program association values.” If the sponsor controlled the entertainers’ entire program (as was the general rule in radio and early TV) and a specific program star was associated with the sponsor’s product, it could foster audience affection for the performer. When the advertised product was also one that could be linked in audiences’ minds to pleasure, then it could be matched to a like-minded, lighthearted comedy show and happy audience associations would result. Jack Benny and Jell-O could become cemented together in consumers’ minds, and listeners would purchase Jell-O to applaud Benny. When the plan succeeded, Weaver called it an “explosive kind of selling.”11

On the other hand, the 1959 copywriters’ guide that quoted Daniels reminded its readers that not every sponsor or advertiser approved of the soft sell approach of intertwining ads and entertainment. George Washington Hill practiced the exact opposite approach with Lucky Strikes, relying on “the shock value of a commercial that contrasted violently with the entertainment.”12 Advertisers like Hill worried that a comedy commercial would too easily be forgotten. Jack Benny’s genius would be to merge soft and hard sell techniques completely in his comedy, hammering home brands names in a hilarious, absurd, and sometimes shocking manner, which worked effectively for sponsors as disparate as manufacturers of soda pop, automobiles, tires, desserts, and cigarettes.

THE EFFERVESCENT RADIO COMEDIAN’S AUDACIOUS

COMMERCIALS

The advertisements that ginger ale bottler Canada Dry placed in newspapers, magazines, and on the radio in the late 1920s and early 1930s (created by the N. W. Ayer and Sons agency) emphasized dignity, social class, and good taste. Canada Dry’s ad managers had modified the hard sell by developing soft(er) sell themes that stressed the atmosphere of refinement surrounding the product, calling it the “champagne of ginger ales” and describing the beverage’s popularity among the country club set.13 Canada Dry radio advertising was presented by a stately announcer with a cultured, well-modulated voice. Nevertheless, soft drinks were a pleasurable, frivolous treat, not a life necessity or something available only to the rich. The product was inexpensive, and commercials educated consumers to order it at soda fountains and to purchase take-home bottles from their grocers—not exactly the daily habits of the Rockefellers.

In April 1932, Canada Dry, which had been sponsoring radio programs for several years, was dissatisfied with its action drama set in the snowy Canadian Northwest Territories, broadcast on NBC. They’d gotten a few too many complaints from listeners about the show’s violence, and objections from potential customers always put sponsors in a panic. So NBC executives Bertha Brainard and John Royal searched for a replacement to present to the sponsor and its advertising agency. Canada Dry dithered between sticking with dramatic narratives that made listeners think of Canada, or switching to a light, pleasant musical and “personality act” like the shows currently on the air featuring bandleaders Ben Bernie and Fred Waring. Canada Dry warily agreed to try a program pairing bandleader George Olsen and his orchestra with Jack Benny. In his contract, ad agency N. W. Ayer and Sons stipulated that Benny would “handle the commercial credits” at midprogram himself.14

Jack Benny took it as a challenge to use the commercials to explore the satirical side of living in an urban world increasingly filled with sales pitches. On the first program, May 2, 1932, Benny launched into humorous commercials with a vengeance. Describing his meager girlfriend in Newark, Jack claimed:

She comes from a very fine family, although her father very often partakes of the forbidden beverage. It’s all right for me to mention that, as they have no radio. In fact, her father drank everything in the United States, and then went up north to drink Canada Dry. (whistles) Gee, I’m glad I thought of that joke—you know—the one about Canada Dry, I’m really supposed to mention it occasionally. After all, I owe it to my sponsors, and they might be listening in. Seriously though, do you realize, folks, that if you want a drink of Canada Dry—we’ll say just a glass—you don’t have to buy it by the bottle. You can walk into any drug store or soda fountain that has that big sign, “Canada Dry made to order,” ask for a glass, and get it. I know you always have it in your home in bottles, but isn’t it nice to know that you don’t have to wait until you get home to drink it? Gee, I thought I did that pretty well for a new salesman. I suppose nobody will drink it now.

Benny violated what most advertising executives considered a cardinal rule. As Draper Daniels would mandate, “Humor may be directed at the salesman of the product, the user or nonuser of the product, or at the foibles of human nature and society. It must never be directed at the product. . . . Irony, satire and subtlety are likely to miss with a mass audience.”15 Benny proceeded to push the envelope edges of vaudeville-like slapstick verbal humor with his Canada Dry commercial messages over the next few weeks of the broadcast.

On the May 23 episode, with Harry Conn on board, Benny’s target was the patent medicine commercials that littered the radio landscape with their ridiculous claims of cures, their gruesome details of indigestion, acne, and constipation and the suffering of victims that could only be relieved by purchasing the miracle product:

Jack—Let me say this, ladies and gentlemen, I do not claim that Canada Dry will cure falling arches, dandruff or baggy knees. But I will say this—I KNOW it is a refreshing drink because last night—believe it or not—I tried a glass of it at the fountain. And it wasn’t bad . . . it was NOT bad . . . in fact, it was good . . . I liked it. . . . Gee, I thought it was swell . . . Ladies and Gentlemen, it was EXCELLENT! . . . Are you paying attention, Sponsors, hmmmm?

The sponsor was appalled, as these ads shattered the atmosphere of dignity and refinement surrounding the product that they were paying their agency so much money to maintain.16 Years later, Benny recalled the turmoil:

The first few weeks that we did it in a satirical way on the Canada Dry show, the sponsor didn’t like it and want us to stop it. . . . We did a lot of satires on the commercials [like “nickel back on the bottle”]. The sponsor wanted us to go back to the straight commercials but the agency liked it and the agency said “they haven’t had time to prove whether this is a good way to do it.” So they allowed us another two or three weeks. And in the next two or three weeks the mail kept coming in so much to the sponsor that they liked this kind of advertising that they finally let us alone and let us do it.17

Benny’s Canada Dry commercials cynically ribbed the product with far sharper barbs than other radio shows were doing. The Albert Lasker/eventual Draper Daniels school of advertising would have been shocked to see such levity as the Depression’s economic woes were growing ever worse. They fully captured the spirit, however, of the over-the-top parody advertisements then appearing in the satirical humor magazine Ballyhoo, edited by former Judge magazine cartoonist Norman Anthony, which had debuted in Manhattan in August 1931 and had quickly grown in circulation to sell nearly two million copies per issue. Historians Margaret McFadden and Roland Marchand have analyzed how the magazine’s comic strategies sharply critiqued capitalism’s failed promises and the ridiculousness of Prohibition, burlesqued the humbug of advertising practices, and provided a devastatingly pointed and bitter humor that mocked big business and the social class inequities that favored the wealthy. Ballyhoo was read gleefully by a public battered by economic devastation.18 Ballyhoo printed a fake ad for a souped-up international radio console that offered to provide “All the crap in the world at your fingertips!”: “Now you can hear foreign announcers gargle hot potatoes . . . it will do everything in the world but give you good programs and Gawd knows no set will do that.” The magazine’s success spawned a book, a board game, and an off-Broadway revue, Ballyhoo of 1932, featuring a young Bob Hope, which was playing that summer when Conn and Benny devised their own satirical ads.

Benny and Conn’s commercials deprecated the product, the sponsor, and the practice of visiting soda fountains. Benny claimed that Canada Dry was conducting scientific taste tests, blindfolding factory workers, or tying them up, or approaching desperate, parched tourists who had been stranded in the desert, forcing these poor souls to sample the beverage and reporting that they claimed their sip of Canada Dry was not objectionable. They created a product spokesman, a talking glass of ginger ale with a high-pitched cartoon voice. Benny associated Canada Dry with Mary telling a risqué story about a peeping tom in a train’s sleeping compartment, and jokes about homosexual zoo animals, lazy soda jerks, drunks, and stories of torture and cannibalism. If Benny and Conn were pushing the boundaries of acceptable humor, at least they were gaining critical and popular acclaim from their small but growing listening audience. Benny became associated with the advertising catchphrases they coined; Jack became known as “Nickel Back on the Bottle Benny.”19

The Canada Dry program was joined by several other radio programs experimenting with integrating humor into their commercials, such as the Texaco, Pabst, and Chase and Sanborn shows. Variety’s Ben Bodec commented, “With the improvement of entertainment and production levels has come a change of policy in the handling of the plug. Devious ways are being introduced for feeding it to the listener insinuatingly. . . . The Ed Wynn, Ben Bernie and Jack Benny sessions show that the product’s plug can be kidded and at the same time put over effectively.”20 Other programs that attempted a comedic advertising vein were excoriated by industry critics. Variety’s reviewer criticized the Gem Razor program with Bert Lahr, for its “bludgeon type of merchandizing.” The show’s performers were guilty of “doing an awful lot of nudging of ribs to remind listeners that Gem is twice as thick, much sharper, smoother, cheaper, and smarter. It deprives the program of its charm and tends to leave behind a hostile impression.”21

In his fourth month of broadcasting for Canada Dry, Benny lost the role of chief commercial-kidder—no more squeaky-voiced talking bottles or write-in contests, or crazy commercial monologues. Perhaps the sponsor and agency had finally had their fill. The integrated commercial bits now focused on the program’s announcer, an obnoxious boor (played by the erudite George Hicks, who read the opening and closing ads in a dignified manner) who burst unexpectedly into skits and interrupted conversations with shouted-out hard sell plugs for product.

Despite positive critical reaction to the advertising and entertainment, Canada Dry remained dissatisfied with Benny’s handling of the program (as we saw in chapter 1) and cancelled its sponsorship on January 24, 1933. Benny next learned that there were pitfalls in being too closely associated with a particular product. He found that few sponsors would consider him, concerned that he had become so closely associated with Canada Dry Ginger Ale that radio audiences would reject his commercials for other products. Old Gold cigarettes passed on working with him. Benny only acknowledged his frustration and humiliation twenty years later on his radio show, through a joking comment made by Mary Livingstone, that she pulled Jack out of his car, trying to kill himself with carbon monoxide poisoning, when his first sponsor fired him.22

In late February 1933, after several other radio entertainers changed sponsors without the sky falling, NBC finally convinced the Chevrolet automobile company to pick up Benny’s option.23 Chevrolet was dealing with daunting challenges of its own. The winter of 1933 was the nadir point of the Depression, with lame-duck President Hoover powerless to stem the tide of bank failures, unemployment, and despair flooding over the broken U.S. economy. Who could even think of purchasing a new car? Chevrolet was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. Radio was the one bright spot in American advertising, so program sponsors counted on it to provide miracles like Amos ’n’ Andy continued to do for Pepsodent toothpaste sales. Chevrolet had been sponsoring a radio musical program starring Al Jolson, but the temperamental singer suddenly quit his contract. Benny agreed to pick up the final six programs of the season, with Frank Black leading an NBC house orchestra.

The new Chevrolet program debuted on one of the least auspicious dates possible, March 3, 1933, the night before Franklin D. Roosevelt’s inauguration. Maybe the Benny gang’s cut-ups helped momentarily assuage the “fear” that FDR would focus on in his next day’s speech. Even Chevrolet’s opening commercial acknowledged that economic worries were paramount on listeners’ minds–“Ladies and Gentlemen: if you have some money to invest and are wondering where to put it—here’s a suggestion, Take that money of yours and use it to buy a new Chevrolet Six. There’s no safer, sounder investment than the purchase of an automobile.”24

Howard Claney became the program’s sixth announcer. Like George Hicks before him, Claney interrupted the characters’ dialogue with self-important announcements about new Chevrolet cars. The comic advertisements now were significantly less biting in tone than what Canada Dry had allowed.25 In October 1933, after an anxious three months off the air when GM withdrew from advertising, Benny’s program was shifted yet again, this time to Sunday evenings at 10:00 P.M.26 Benny was able to carry over bandleader Frank Black, but he had to take on yet another new announcer, Alois Havrilla, and new tenor Frank Parker. Both, however, soon became accomplished comic performers under Benny’s tutelage. The Chevrolet show gained steadily increasing audiences, higher ratings, and critical approval. All seemed to be going well for the program, Variety praising it for

the well-conceived kidding manner of the sales delivery, striking a new high in humorous exploitation and likewise a new evolution of that style of plugging. Announcer Alois Havrilla brings in a comedy ad plug that commands good humored respect for its general ingenuity. Along with that, Benny’s series of travesties on current plays or pictures permits for a world of latitude . . . and a sock of plugs for Chevrolet.27

Suddenly Benny’s sponsor again threw a monkey wrench into his operations. Marvin Coyle was elevated to the position of Chevrolet’s general manager in October 1933.28 Coyle preferred classical music to the current popular band tunes and comedy featured on Benny’s program. Coyle instructed the Ewell Campbell ad agency to reduce Benny’s humorous patter to only five minutes and have the musicians fill the half hour with “romantic melodies.”29 Furious, Benny told the sponsor the he flatly refused to either truncate the comedy or change the music, as he felt that light comedy needed light music. He threatened to quit the program immediately if Coyle’s changes were made. While this ultimatum temporarily worked for Benny, Coyle cancelled the program on April 1, 1934, and instead picked up a musical program featuring Victor Young’s orchestra.30 Chevrolet car dealers in Nebraska and elsewhere expressed their frustration with the show’s cancellation, as they had considered Benny’s program a helpful marketing tool: “Benny’s programs rate high in this section and seems to have been a good warming point for the salesmen to start off their song and dance with when a customer comes in. . . April finds the heavy selling just getting under way and with the good listener [program] out, it’s unfortunate.”

Chevrolet’s top executive dictating the content of its sponsored radio shows entered ad agency lore as one of the most boneheaded moves of all time. A 1951 article in Sponsor instructed corporate executives to heed Chevrolet’s mistake:

The sponsor must be on guard against his own private prejudices. Classic is the incident of the Chevrolet tycoon who passed by Jack Benny just at the start of Benny’s first nationwide wave of popularity because he, the tycoon, personally preferred classical music to jokes. Big man though he was, this sponsor was wrist-slapped by the General Motors high command for allowing purely personal preferences to determine corporate decision.31

The very public firing mortified Benny. In subsequent years, even when he could joke about being released by Canada Dry, Benny never spoke publically about the Chevrolet episode, maintaining that his show moved directly from Canada Dry to his next sponsor, General Tire.32

BENNY GAINS GREATER PROGRAM CONTROL

In April 1934, as NBC executives beat the bushes to locate a new sponsor for Benny’s very expensive program at midseason (and not lose him again to CBS), Bertha Brainard alerted president Niles Trammel to Benny’s growing list of demands. Having now done battle twice with sponsors who wanted to alter his show, Benny would have no more of it. His program’s steady rise in the ratings gave him significant bargaining power, despite the two cancellations, to secure greater creative control.

Benny first sought to be able to make more of the casting and hiring decisions. Benny wished to provide more of a complete “package” program to present to a potential sponsor. Benny could count on Mary Livingstone’s services, of course, and he had paid writer Harry Conn out of his own earnings since 1932. Now he sought to employ his own announcer. It was an indication of how important keeping that comedic element of commercials integrated into the program was to Benny that he chose to hire the announcer, rather than a singer or band leader (they would still be under contract to the sponsor, ad agency, or network).

Second, Benny wanted more control over where he broadcast from, and what he did in between weekly episodes. In 1934, Benny increasingly began traveling back and forth to Hollywood to make movies, and MGM pressured him to make a full slate of films. NBC and most East-Coast-based sponsors were very unhappy, however, with the idea of Benny broadcasting from California. They tried to prevent it, or put major restrictions on where Benny could broadcast the radio show. Benny sought to be able to take his cast west, even though it might mean having to pick up a different orchestra, bandleader, and singer in Los Angeles, as bands based on either coast sought to play steady engagements during the week to supplement their radio incomes. Making personal appearance tours at major theaters across the United States was a significant boost to Benny’s own income between radio broadcasts, and Benny sought more ability to take the radio cast on the road to maximize their public exposure and income opportunities.

Bertha Brainard reported to Niles Trammel that “Benny insists clause be in contract permitting him to make pictures in Hollywood at any time he can. He to pay wire charges. Also clause in contract definitely stating program formula and his style must be accepted as is and at no time will he permit direction from agency or client on style of program.”33 She also warned Trammel, “Again wish to emphasize Benny on General Tire follows Ed Wynn and we believe it would be bad programming and are not in accord with idea.” Benny was frustrated about his lack of input into decisions about where his program fell in the network’s evening schedule. In the same way that vaudeville bills had been organized not to place the comics one right after another, Benny did not want his quiet humor to follow a raucous comedy program. NBC offered little help in this regard, as radio program scheduling in the 1930s was far more organized around sponsors “owning” of specific schedule times as opposed to the network building a strong lineup of programs that would help each other build audiences.

Brainard finally located a possible sponsor. General Tire had been sponsoring a dramatic show called Lives at Stake, but some listeners thought it too violent.34 However, the company had relatively few advertising funds available—the tire industry had been devastated by the Depression, and close to 80 percent of workers in the chief rubber production center of Akron, Ohio, were then unemployed. General Tire was only able to afford a six-month sponsorship. To get Benny back on the air in midseason, the radio program’s broadcast time shifted again, to Friday evenings at 10:30 P.M., and the show had to pick up yet another new orchestra leader (Don Bestor), but was able to retain popular tenor Frank Parker.

Benny hired Don Wilson to be the eighth announcer on the program in two years. Instead of just having Wilson shout advertising slogans, Benny and Conn slowly returned the comic integrated commercials back to more of the silly things they had done with Canada Dry. Wilson soon blossomed as a fine comic stooge and became a full member of the cast; in skits parodying romantic melodramas, Don’s character climbed ladders to help Mary’s character elope; Jack began joking about Don’s girth. Jack and Don played a hilarious sketch in which Don invited Jack out to the Wilson home for the weekend to meet his parents, with disastrous results. Fans responded enthusiastically. Marya Davis of El Paso, Texas, won a $10 prize from fan magazine Radio Mirror for a letter on how that “necessary evil,” of commercials might be converted into a program asset. “Advertising can be both funny and effective—if made part of the program itself. Consider the riotous way Jack Benny sandwiches in references to General Tire. We don’t resent such advertising because it is presented humorously.”35

Come October 1934, it was time to switch to the alternate sponsor, which would mean upheavals in broadcast time and agency management. General Tire tried to make the best of the awkward change-over. Don Wilson read a telegram on air sent by Bill O’Neill, president of General Tire, to Jack:

Except for your interference on these programs, Don Wilson could have told our audience much more about our new corkscrew tire. You insist the show’s the thing, and on that score I want to compliment you and the cast on 26 weeks of fine entertainment. Until we resume these programs next March, you will be broadcasting for General Foods. The only connection between General Foods and General Tires is that we eat their products and they wear ours. You have to eat to live, but you have to live to be able to eat—so the more people we put on General Tires, the more customers we keep for General Foods.36

The 7:00 P.M. Sunday slot in which General Food’s Jell-O division scheduled the Benny show was a no-man’s land for radio entertainers and sponsors alike. While Eddie Cantor had been able to pull in massive audiences with an 8:00 P.M. Sunday program, others (especially anything earlier) fared poorly, making Sunday overall the lowest rated night of the week.37 Early Sunday evening presented Benny with audience taste challenges. Conservative Christian families attended church services on Sunday evenings and might not be available, or would decline to listen. Many families were eating Sunday dinner—would they be too preoccupied to listen? Other families travelled to visit relatives or took Sunday drives out into the countryside, and while a growing number of automobiles now featured radios, would passengers tune in Benny’s radio program while on the road? For two years, Benny’s program had been broadcast late in the evening, usually after 10:00 P.M., and critics thought his humor was sophisticated and adult focused (if rarely blue). Now he was going on the air three hours earlier. Would Benny’s humor be considered appropriate for all members of the family audience? Furthermore, a program at this early edge of the prime time evening schedule had no lead-in shows preceding it to build a ready-made audience. Broadcasting a comedy program on early Sunday evening was a gamble only a desperate sponsor might make.

JELL-O—A PRODUCT IN DIRE STRAITS

A forty-year-old gelatin dessert product, Jell-O was a lead weight in the General Foods brand portfolio. Sales had fallen by two-thirds since the company had been incorporated into the General Foods conglomerate of packaged food lines in 1924. Jell-O’s problems were threefold. First was the product itself—it didn’t taste as good as the competition and took a long time to prepare. Packaged gelatin was one of the most processed food products imaginable, fabricated from ground-up cow and pig hides and hooves, with artificial colors and flavors added to the sugar that filled 60 percent of the box. In 1933, General Foods’ chemists improved the fruit oils used in creating Jell-O, expanded the flavor range to six flavors, and reduced by half the time it took housewives to fix it. A second problem was Jell-O’s outmoded marketing focus. For the previous forty years, most of Jell-O’s advertising had been addressed to children; magazine advertisements featured the pretty blond “Jell-O Girl,” cartoon zoo animals, and illustrations of children preparing the product (to demonstrate how easy it was to make, and how fun it was to eat). Competing products, however, were appealing to sophisticated young homemakers.

A third problem was even more deadly. Fortune Magazine reported that General Foods’ operating principle was to “take an unnecessary but established product, dress it up with all the art of the industrial designer, spend plenty of money in advertising it, sell it with every variety of high pressure that the art of the sales promotion manager can devise, and try to collect a long profit.” However, as in the case of Jell-O, these actions “attract[ed] competitive swarms of smaller concerns which are willing to work at a shorter profit and which more than once have cut ground out from under General Foods products.” Increased competition in the gelatin field was destroying Jell-O’s market share. Royal Gelatin, produced by rival packaged food manufacturer Standard Brands, was considered better tasting. The A&P grocery store chain started marketing its own private label gelatin, Sparkle, and both these products as well as other small label competitors sold for significantly less than Jell-O. Jell-O cost 10–12 cents per package in 1929, while competing brands sold for only 6 cents. Especially as the Depression’s hard times diminished consumers’ incomes, they purchased less expensive foodstuffs. Perhaps only a marketing miracle could rescue this dying product.38

Executives from Y&R pitched to General Foods vice president Ralph Starr Butler a plan to save Jell-O by cutting prices, boosting sales, and redirecting the marketing focus. The ad agency had brought massive marketing success to other General Food brands such as Post Cereals, Postum, and Maxwell House coffee. Y&R, as Cynthia Meyers discusses in her history of radio advertising, was especially devoted to the soft sell approach, and its work with Postum and other General Foods brands in print and on radio demonstrated that advertising could be tremendously successful in creating consumer awareness and emotional loyalty to both the sponsors’ programs and products.39 Now Y&R advocated changing Jell-O’s advertising strategy to focus on homemakers, reduce the product price, and spend much more on radio and print promotions. Despite the Depression, packaged foods represented a growing segment of the American consumer market. Food expenses represented a massive 37 percent of American family budgets during the 1930s. Convenient, inexpensive packaged foods were poised to take a more prominent place in busy families’ market baskets.40

Y&R advised Jell-O’s product managers to drop their current radio advertising sponsorship of a Wizard of Oz–themed children’s program, and instead join one of the most popular trends in radio programming—the comedy/variety program. Most of the top comedians, however, such as Will Rogers and Eddie Cantor, were already locked into long-term contracts. Y&R suggested Jack Benny for the role, but General Foods had concerns that Benny’s was one of the most expensive programs on network radio, and Jell-O’s annual sponsorship costs would triple. Y&R executive Lou Brockway later recalled that “We were very frank with our client in presenting Benny. We said he was not our first or second or third choice but he was available and he had a good, if not outstanding, record.”41 Jell-O’s management cautiously agreed to pick up the program, but warned that product sales must rapidly increase in order for the show to remain on the air.

Under orders to produce impressive results in advertising as well as sparkling comedy, the first Sunday night Jell-O broadcast (October 14, 1934) enthusiastically integrated commercial messages into the entertainment. A chorus introduced the new musical signature, cheerfully singing out the letters “ J-E-L-L-O,” a bit that orchestra leader Frank Black had composed on the fly. After the opening commercial (a newsboy shouting Jell-O headlines), Jack opened the program with a new twist on his regular greeting, turning “Hello again” into “Jell-O again everybody!” Jack joked with Don Wilson about the many ways they could be incorporating the sponsor’s product into the show’s dialogue. Don claimed he had purchased neckties in six colors to represent the six delicious flavors, while Jack quipped that Don has already gotten a strawberry flavor stain on an orange tie. Jack cautioned Don not to be too obvious when he worked mentions of Jell-O into the show, for example, not to say “Los An-Jell-O.” Mary soon entered, spouting jokes about blown-out tire tubes, and the cast laughed that she was a week too late. In the second show, Don broke into the middle of the dialogue in Benny’s parody of the film The Barretts of Wimpole Street. When Mary as Elizabeth cried out that she felt she was lost in the desert, Wilson leapt in to announce, “Speaking of DESERT, you will find that Jell-O is the grandest DESSERT your family has ever tasted, and you can get it in six delicious flavors, strawberry, raspberry cherry, orange, lemon, and lime!” The studio audience laughed heartily at the pun.42

The revamped Benny program was an immediate ratings success, but sales of Jell-O did not budge. Mary recalled General Foods’ anxiety that improvement was not occurring quickly enough for the company to be able to justify the expense of sponsoring the pricey program. On the verge of cancelling the program, General Foods executives mandated that the entire cast take pay cuts. Mary and Jack told the sponsors that they would rather carry the burden themselves, and the two of them worked without salary for weeks to keep the rest of the cast on a living wage. Finally, after three months, Jell-O boxes started flying off grocers’ shelves. Don Wilson in a closing commercial in December 1934 went to great lengths to praise the radio audience for purchasing Jell-O in such large quantities.43 Relieved executives from General Foods and Y&R hosted a cast party at the Benny’s New York apartment, and the sponsor made a show of presenting Jack and Mary with a check representing all of their back pay. Mary recalled her chagrin at being overheard chiding a maid who had appeared with a huge platter of Jell-O (sent by the sponsor) to “put that crap wherever.”

A radio critic in 1951 attested to the powerful synergy that Don Wilson’s vocal talents and friendly personality brought to Benny’s commercials: “There’s much in a voice. It can be strong, vibrant, confident; warm, persuasive, infectious. The voice of [Don] Wilson, currently heard on the Jack Benny Show . . . has these qualities. It has been termed: ‘America’s finest selling voice’.”44 Wilson had first entered into radio in the 1920s in California as a singer and announcer, where his color commentary at Rose Bowl football games and other sporting events brought him attention and an invitation to move to New York in 1932. Jack Benny hired Wilson for the General Tire Program in spring 1934, after hearing him read just a few lines, recalling, “He had a warm voice, he could read a commercial with laughter in his throat, and he proved a great foil to play against.” Descriptions of Wilson emphasized his “beaming good-naturalness” and his “infectious laugh”; he was “the jocular, rotund radio announcer who joked and winced at Jack Benny’s wisecracks” about his extreme girth (in reality Wilson stood over six feet tall and weighed 240 pounds). Wilson soon began placing high in annual polls of best announcers, and earning awards from the Radio Guide, New York World Telegram, and Motion Picture Daily.

FIGURE 16. Unlike previous sponsors’ unease with Jack Benny’s thorough mixture of impertinent mentions of the product into his comedy, Jell-O was pleased to promote his ratings and product sales success. Plymouth Theater program, Boston, November 26, 1934. Author’s collection.

Wilson advised aspiring radio advertising copywriters that “The warmth and acceptability of the announcer . . . who is sincere and whose voice is recognized by the listener as that of a friend in the house. . . . will then make all the difference in the world to the quality of the message itself.”45 Wilson’s personality-imbued vocal performance, matched with expressive, emotional language provided by Y&R copywriters, such as this March 1936 example, turned even the “straight” opening and closing commercials for the Jell-O program into synesthetic sensory experiences for listeners to taste, see, and smell:

One of the strongest influences in our lives, I think, is color; black and white is fine for an etching, but we all need bright colors to keep our spirits up. When it comes to colors, that is where Jell-O shines, it’s the liveliest, gayest dessert you can find. Sunshiny orange, shimmering green, the deep rich tones of rose and crimson, six different colors from which to choose, every one lovely, clear and glowing. . . . And when it comes to taste, AHHH, that is where Jell-O shines again, for its packed cram full of delicious real fruit flavor, flavor as truly luscious as the fresh ripe fruit itself.46

Radio writer Charles Wolfe claimed that the “personalized salesmanship” that the best announcers brought to their performance played the most important role in making radio a potent sales tool. “Radio’s employment of the human voice adds living vitality, immediacy, warmth, sincerity, individuality and persuasiveness which give radio a unique distinction among advertising media and which are largely responsible for its selling power.”47 In this April 16, 1939, closing commercial for the Jell-O program, Wilson explained the synergy between announcer, evocative ad copy, and the audiences’ receptive mood that created such a marketing juggernaut:

A friend of mine paid me a REAL compliment the other day. She said, “You know, Don, when you describe those Jell-O desserts over the radio, you just make me HUNGRY for them.” Well naturally I was pleased, and tonight I have another new Jell-O dessert I know will make a hit with everybody. A combination of raspberry Jell-O and cottage cheese, and I’m TELLING you, Ha, it’s swell and easy to make, too. Dissolve one package of raspberry Jell-O in one pint of hot water and turn into a ring mold and chill until firm. Then unmold it and fill the center with cottage cheese. Serve it with toasted crackers, and THERE is a TRIUMPH of desserts. Clear, shimmering raspberry hello with its EXTRA rich flavor and creamy cottage cheese, SMOOTH and tempting. So try it. Ask your grocer tomorrow for raspberry Jell-O.48

As the purported comment attested, a key aspect of the Jell-O ads’ effectiveness was Don Wilson’s ability, through a combination of his vocal performance and the commercial texts, to make multifaceted appeals to the listeners’ senses and emotions, and make as many positive associations with the product as possible.49

Most of Don Wilson’s integrated mentions of Jell-O do not read humorously in scripted form. The wry comedy came from his tone of voice, quick quips, and butting into dialogue with the catch phrases “big red letters on the box,” “genuine Jell-O,” and six delicious flavors. The name “Jell-O” was sprinkled liberally throughout the scripts, from characters on a ship called the “Jell-O-a” or a family’s children being named Orange, Lemon, and Lime, to skit titles such as “The Count of Monte Jell-O” and “Romeo and Jell-O-ette.” A reviewer claimed to have heard the product name mentioned thirty times in a single show. When Radio Mirror published several Jack Benny program scripts in 1937 to give listeners a way to re-create the pleasure of listening to the show during the late-summer months the cast was off the air, even the scripts included integrated commercials.50 Jack boasted about being a musician and having played the violin in concert halls “long before I knew anything about strawberry, cherry, orange, lemon, and lime.” Don interjected, “You left out raspberry,” and Mary retorted, “I’ll bet the audience didn’t.”

JACK BENNY AND JELL-O MERGE IDENTITIES

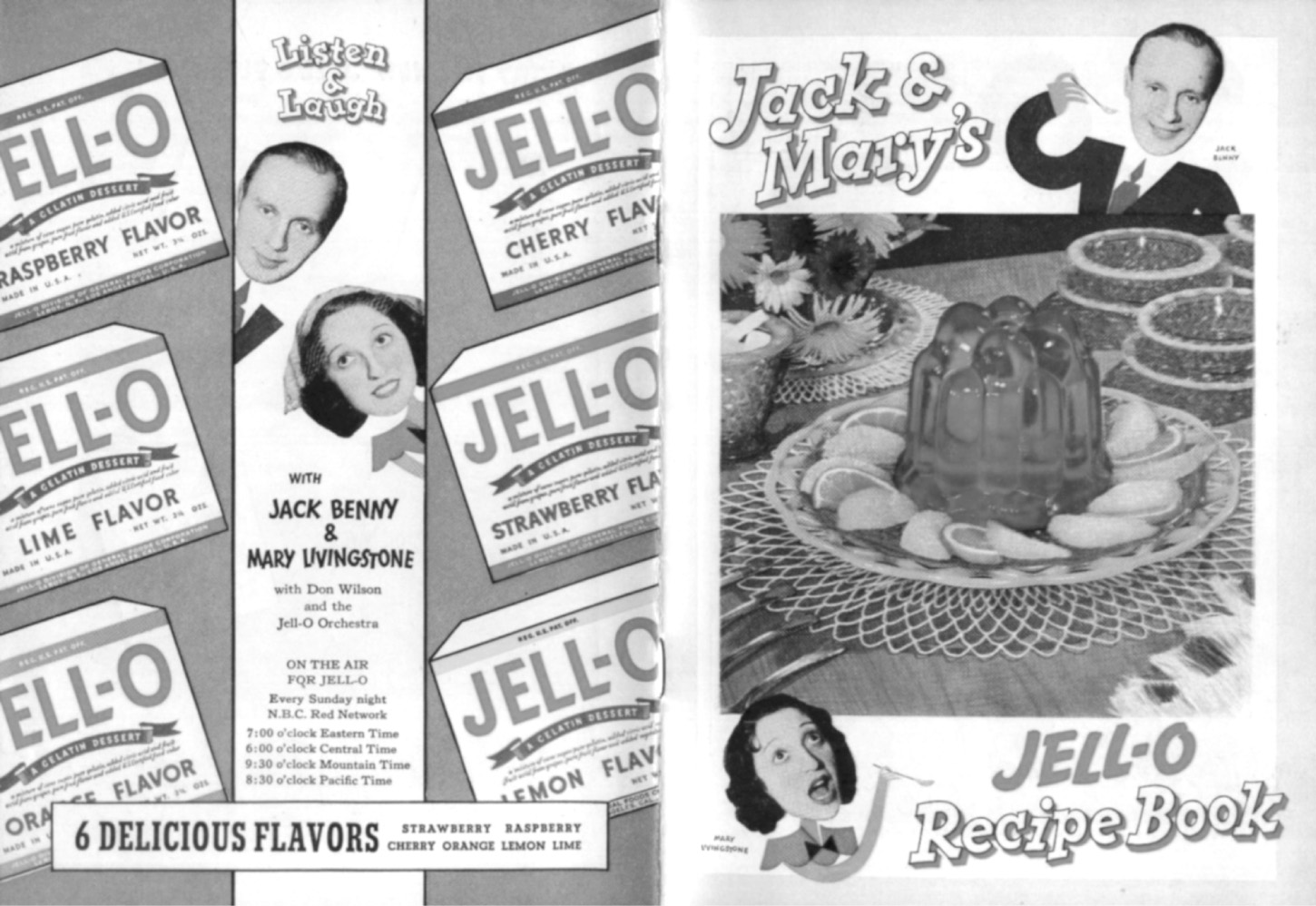

By 1935, Jack Benny had become the embodiment of Jell-O, indelibly associating the product with his light, zany, character-gang-driven comedy. Cartoon images of Benny and Mary Livingstone were found in brightly colored Jell-O ads placed in all the major women’s and family magazines. In 1937, General Foods published Jack and Mary’s Jell-O Book, featuring the stars, photos of their faces superimposed on stick-figure bodies, telling ridiculous Jell-O-related puns and offering elaborate recipes. The booklet was available for a few cents plus some proofs of purchases mailed to General Foods. The company received 67 million Jell-O box tops in response. Confused housewives were said to ask for “Red or Green Benny” at the grocery store. A New York City luncheonette’s bill of fare listed strawberry Jell-O as “Jack Benny in the Red,” and hotel banquet menus offered “Dessert a la Benny.” A 1939 poll of consumers found that 92.5 percent of Jack Benny’s radio audience automatically identified him with his sponsor’s product.51

FIGURE 17. Jack Benny and Mary Livingstone are transformed into cartoon characters happily consuming the playful product in this popular Jell-O giveaway recipe booklet. Millions of copies were given away by mail in 1937. Jell-O booklet, 1937. Author’s collection.

Benny’s connection to Jell-O was also cemented by his film studios. In an elaborate two-page cartoon-caricature ad MGM placed in Variety in November 1935 to promote A Night at the Opera, a cartoon in which Benny took a prominent place among a dozen comics gathered in theater seats to praise the Marx Brother’s “comeback” film. Benny quipped, “A Night at the Opera is great entertainment with its six delicious flavors—strawberry, raspberry, cherry, Groucho, Chico, and Harpo.”52 When Benny and his radio cast appeared onstage at the Paramount Theater in New York in 1939, promoting their new Paramount film Man about Town, Variety’s reviewer marveled, “When Benny mentioned his sponsor, Jell-O, it evoked a burst of applause, probably some sort of record—a dessert being applauded in a Broadway deluxer.”53

The downside of this close identification of Benny with Jell-O, for the sponsor, was if Benny garnered negative publicity. That is what happened in 1939 when Benny and George Burns were indicted in federal court on jewelry smuggling and tax evasion charges. Newspaper headlines across the country blared sordid details of the case. Benny was terrified that his program would be canceled and his career would be ruined. His sponsor was nervous about public backlash. NBC executives forbade network comics to joke about the case on the air.54 The advertising trade press declared it risky to have too much dependence on individual celebrities to sell their products.55 Fortunately for Benny and Burns, the judge slapped them with a sizable fine rather than jail time, and with help from Y&R, they were able to overcome the incident.

Jack Benny’s success in the 1930s mingling entertainment and product marketing took place in a climate of growing public outrage against radio’s domination by commercial advertising. Between Dr. Brinkley’s goat gland shilling, and the never-ending stream of loud, obnoxious ads for products to combat bodily malfunctions, consumer groups, critics, and the public were increasingly raising objections. An April 1936 Billboard review of a new Lever Brothers comedy program featuring Ken Murray claimed that the unfunny ads intruded vulgarly and aggressively into the body of the program, and held up the Jell-O program as an unmatched model.

It was Jack Benny, who, we believe, started the vogue of referring via gag material to his sponsor’s product. But there is only one Jack Benny. And everybody who knows the degree of Benny’s wit and personality register compared with any other comedian on the air will admit that only Benny can talk about Jell-O and its flavors without working up a feeling of revulsion in the listening audience.56

Despite, or perhaps because of, the widespread criticism, accolades for the Jell-O commercials accumulated.57 In 1938, Benny’s commercials won an award from the 10 million members of the Women’s National Radio Committee for “first place for good taste in advertising.”58 In February 1940 the trade journal Advertising and Selling presented Y&R with a “Medal Award” for the “appetizing” tenor of its Jell-O commercials:

Attracting and holding attention, explains Y&R, building conviction and stimulating sales have all been done in an APPETIZING manner. By deftly blending salesmanship with entertainment—keeping it always a part of the program, this series has demonstrated to listeners and broadcasters alike what effective selling by air can mean. Don Wilson’s jovially reiterated sales points, like “six delicious flavors” and “look for the big red letters on the box,” have become national catch phrases. Further evidence of this continuity skill is found every Sunday night, when commercials woven into the body of the show draw delighted, spontaneous applause from the studio audience. When consumers can be subjected to advertising—and LIKE it—the advertiser can be sure the job is being well done.59

Ad agencies played essential behind-the-scenes functions in the 1930s and 1940s in the creation of top radio programs (developing concepts, casting, scripting, and packaging). Assessing Y&R’s role in the success of the Jell-O program, agency vice president Everhard Meade recalled,

Y&R didn’t build the Benny show—Benny built it. But in building it, he had agency guidance, counsel and help [with] production at every turn. As in other historical cases, an agency played the crucial role. Enough enthusiastic, skilled people had faith at the right time to go to bat for Jack in the now forgotten days when it was touch and go whether the great man would get his first Jell-O renewal.

Meade claimed that Y&R’s most important service to radio sponsors included “the act of going out on a limb and saying to a client: ‘Because we think so, because research backs us up, because we have a damn good hunch, buy this show—it costs a million bucks.’”60

Y&R was staffed with young creative minds who believed in the promise of radio promotion for inexpensive packaged food, drug, and toiletry products. Benny worked with talented people at this agency with whom he would work frequently during the rest of his career, including Pat Weaver, Tom Harrington, Ted Lewis, Don Stauffer, and Bob Ballin. Y&R’s radio department was hugely successful in the 1930s in handling their radio programs, sensing when to leave them alone and when to tweak them. Y&R staffers knew how to work with performers, too. Weaver especially endeared himself to Fred Allen and Jack Benny, running interference for Fred Allen to spare the prickly star unnecessary interactions with broadcasting bureaucracy. Weaver recalled that “Allen hated agencies, clients and networks indiscriminately.” According to Allen, Weaver’s efforts “at least made life bearable.’”61

Despite their vital importance to Benny’s work, records documenting advertising agency interactions are largely missing both from Benny’s archives and their own. Benny and his writers created an omnipotent “Sponsor” character for the radio program, who could reduce employee Jack to a quivering heap with a phone call or telegram. The Benny program’s workplace situation comedy narrative of the 1930s and 1940s, however, did not include characters from advertising agencies. Agencies remained invisible in Benny’s narrative world until the early 1950s, when American Tobacco switched its account to Batton, Barton, Durstine, and Osborne (BBDO). Benny and his writers then occasionally incorporated jokes into the program about the name BBDO sounding like boxes falling down some stairs, and Jack briefly dated a flirtatious secretary who worked for “Lil’ Old Mr. Osborne.”

With so little documentary evidence of Jack Benny’s relationships with his ad agencies, I will relate only one story from December 1936, when Y&R executives brainstormed a publicity idea. Jack Benny and Fred Allen had been acquaintances (if not close friends) for years in vaudeville and radio. In fact, Benny mentioned Fred Allen on his early radio programs more often than any other comic. It was nothing more than an offhand jest on December 30, 1936, however, when in the talent show portion of the Town Hall Tonight program, Fred Allen complimented the violin performance of young Stuart Canin, by saying Benny would be envious of the boy’s prowess. By chance, in the earlier, scripted half of the episode, Allen and his partner Portland Hoffa had mentioned Benny. Ditzy Portland claimed that Jack’s latest film release was “Benny’s from Heaven” (having confused it with Bing Crosby’s movie Pennies from Heaven). Fred took the opportunity to disparage both Jack and his hometown of Waukegan. Perhaps Benny was on Allen’s mind as a target that evening.62

There is little firm evidence of what happened next. Only years afterward, industry insiders admitted that it was a Y&R executive who suggested to Allen and Benny that they cook up a fake dispute; not coincidentally, Y&R handled both programs. The agency publically denied any responsibility, so that Benny and Allen could maintain that the feud sprang up organically. It would make much better publicity fodder that way.

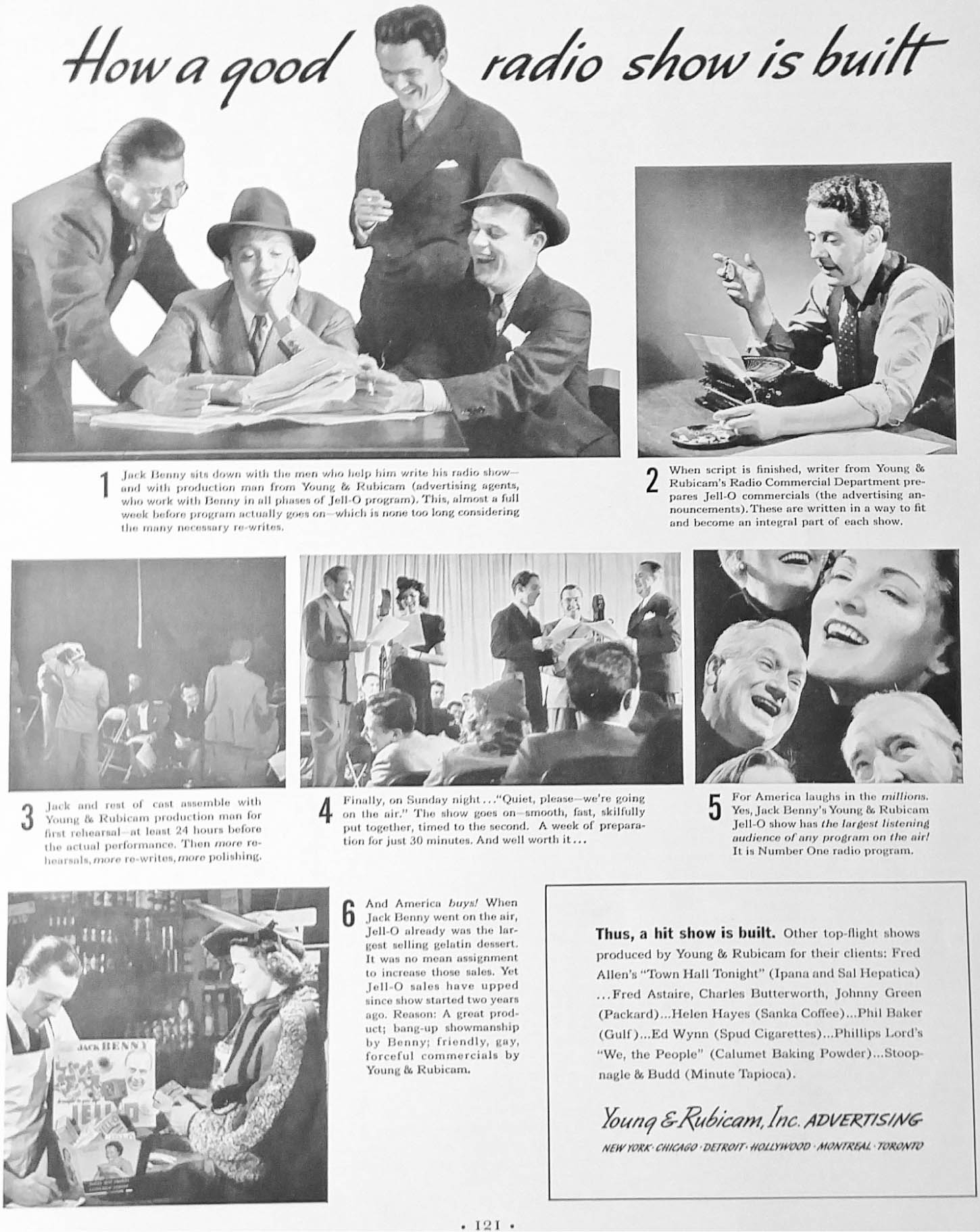

FIGURE 18. Young and Rubicam, the advertising agency for the Jell-O program, maintained that their “soft sell” approach which completely integrated advertising and comedy in their top show, not only made the Benny program highest in the ratings but brought awards for commercial writing, and sold the product at extraordinary rates. Young and Rubicam ad, Fortune, February 1937, 121. Author’s collection.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette radio columnist S. I. Steinhauser was one of the few journalists to spill the beans on the manufactured Hatfield and McCoy gimmick: “All of this ‘shooting’ is the smart idea of one Don Stauffer, a former Scottsdale, Pa. boy, who directs programs for one of radio’s biggest advertising agencies.”63 Apparently, fast-thinking Don Stauffer suggested to Benny and Allen in mid-December that they turn the incident into a continuing media event. Fred Allen’s program scripts from these broadcasts contained a separate section added to the show with up-to-the-minute Benny insults that played off barbs that Benny had thrown just three nights before.64

Allen’s portion of the feud was launched on his January 13, 1937, program. Benny retorted the next week with injured reactions and returned threats. Allen’s program followed Benny’s Sunday program on Wednesday nights, and for nine weeks the entire nation eagerly anticipated the exchange of insults. Before its denouement on March 14, 1937, the Benny-Allen feud garnered hundreds of stories in the press and fan magazines, a publicity and ratings bonanza for their shows. Y&R executives patted themselves on the back for a superb stunt. Steinhauser noted at the feud’s conclusion how it had benefitted the performers as well as the ad agency, sponsor and network:

Fred Allen is dumb like a fox. Since he started his “feud” with Jack Benny, his program has moved up 5.1 percent in coast to coast popularity, according to the latest accepted survey. Jack has moved up only one-tenth of one per cent, according to the same survey. Which proves that Fred has the upper hand in the “argument” if surveys mean anything. But Jack is still Number One comedian, according to the survey and has been for years. . . . Our personal choice in a “feud” is Fred Allen because he is faster on the trigger, writes his own quips, ad libs many of them—a thing Jack Benny simply can’t do—and can move his jibes at Jack in and out of the full hour program without spoiling the show. Jack, on the other hand, plans an attack on Fred, shoots the works, and then returns to his program routine.65

The comedians got the last laughs, however. The idea of the feud provided priceless material for the two performers for years to come, long after they had acquired new sponsors and ad agencies. The public loved playing along that Benny and Allen were bitter enemies, and delighted in their inspired verbal sparring over the years when the two met to insult each other, to vie for sponsors, to recall who had the superior vaudeville act, or to satirize the other’s radio narrative formulas.

LEAVING JELL-O, AND GETTING LUCKY?

Despite the award-winning commercials, enormous product sales, and synergistic fame that the relationship brought both Jell-O and Jack Benny throughout the 1930s, fissures in the Benny–General Foods collaboration nevertheless grew. Benny tussled with Y&R over the control of cast member contracts. The agency had insisted on managing Kenny Baker, the young tenor Benny had developed into a rising star. Y&R did little to hold Baker, however, and he left the program, and Benny in the lurch, in spring 1939. (Benny was, however, able to put Baker’s replacement Dennis Day under personal contract.) Benny refused to renew his own Jell-O contract in spring 1940 unless he was given absolute control over the cast, orchestra, sound effects, writers, and producer in the future,66 and thus negotiated the strongest management held by any performer in the radio industry.

By late 1940, General Foods found that they were reaching the upper limits of Jell-O sales. The corporation had already added two extensions to the product line, Jell-O Puddings and Jell-O Ice Cream Mix, to ride on the coattails of Benny-generated sales success. The company spent $790,000 for 39 weeks of the Benny program, a cost that represented a little more than 2 cents for each dollar of Jell-O sales (at 6 cents retail per package). Jell-O sales accounted for 25 percent of all General Foods income, but the corporate accountants could not advise continuing this enormous marketing expense.67

General Foods needed their expensive but successful salesman to remain in their fold and advertise other products, but Benny balked. He didn’t want to lose such a rich and colorful source of humor, and the sponsor’s plan to switch him to the Grape Nuts account was unappealing. Benny flirted with Old Gold cigarettes and Campbell soups. General Foods, Y&R, and NBC executives scrambled to placate the comedian. Campbell’s was nearly successful in stealing the comic, and industry gossip said that only heroic efforts by Y&R’s Tom Harrington and NBC’s Bertha Brainard kept Benny and General Foods together.68 Y&R made tremendous hoopla over a celebration of Benny’s tenth anniversary of broadcasting, with awards, dinners, and commemorative sections published in the trade papers. NBC came up with the last-ditch idea of “gifting” Benny with the Sunday 7:00 P.M. time slot, which would be forever his, no matter what sponsor he was with, an entitlement that had never previously been granted to a performer.69 These compliments (and a raise) closed the deal in April 1941, and Benny remained with Jell-O.70

Just twelve months later, however, sudden wartime sugar rationing in spring 1942 curtailed Jell-O production, and the gelatin division could no longer afford Benny. General Foods announced that it was switching Benny’s program to Grape Nuts and swapping in the significantly less expensive to produce Kate Smith program. Cereal supplies were not limited, General Foods optimistically reminded Benny.71 Unfortunately, no matter how Benny’s writers tried, Grape Nuts and Grape Nuts Flakes were just not as ripe for silly commercials as Jell-O had been, with a few exceptions like the Twink Family skits in 1942 (discussed in the Mary Livingstone chapter).

By early 1944, Benny had grown weary of General Foods. Despite the outward happiness of their relationship, Benny was frustrated that his ratings were steadily declining, and the sponsor was not supporting his program with sufficient investment in advertising and public relations to help him regain ground.72 Benny put his show up for bid. He had complete control over NBC’s Sunday 7:00–7:30 P.M. time slot, which he had done much to build into what was now the preeminent broadcasting segment in all of network radio. General Foods thought differently—they had financed the Jell-O broadcasts and thought the time slot should remain theirs, and fought hard to keep Benny. “There were five different companies that went after whatever deal we wanted,” Benny later recalled. “The two of them we were trying to decide on were Campbell Soup and American Tobacco and I finally picked Lucky Strike because of a man in the agency [Don Stauffer] that I happened to know who represented Lucky Strikes at that time.” Despite the dreadful reputation that American Tobacco had earned for its outrageous ads, Stauffer convinced Benny that he could run interference with one of the most fearsome sponsors of them all.73

In February 1944, Variety headlines proclaimed that the American Tobacco Company had snared Benny for Pall Mall cigarettes.74 Benny’s requirements included nearly complete control of the program’s writing, casting, and payroll, time off in the summer, and flexible scheduling to allow him to make personal appearance tours, radio guest appearances, and to work in motion pictures. His new sponsor not only upped Benny’s salary package by 10 percent but also promised Benny a three-year contract, and a $250,000 “slush fund” budget for public relations expenses. Variety said that George Washington Hill was “so desirous of obtaining Benny that he is willing to offer all kinds of concessions.”75

Benny, the master of soft sell advertising, was taking on a huge new challenge in working with Hill, creator of the most irritating and obnoxious ads on radio. Model for the rapacious, impossible sponsor Evan Llewellyn Evans in Frederick Wakeman’s 1946 tell-all novel The Hucksters,76 Hill was an advertising evil genius and lived for selling Lucky Strikes and his other cigarette brands by any means.77 Hill had been an early adopter of radio advertising, sponsoring the Lucky Strike Dance Band beginning in September 1928, underwriting programs of popular hits and dance music for three decades. Hill was infamous for forcing NBC president Aylesworth to dance to the broadcast tunes with Bertha Brainard while Hill looked on, to make sure the tunes appropriately fit his standards of dance music.78

Lucky Strike’s radio advertisements were notorious for obnoxious slogans, shouting commercials, and vulgar brashness. Earlier print ads had touted “Reach for a Lucky instead of a Sweet,” and “Its Toasted.” Shouting announcers in 1940s radio ads proclaimed “Lucky Strike green has gone to war!” Such huckstering didn’t seem to correlate with Benny’s smooth style of advertising humor at all. January 1944 (several months before Benny negotiated with Hill) had seen and heard the debut of Lucky’s “LS/MFT” (Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco) campaign.79 The sloganned letters, endlessly repeated with lines of “triphammer” copy, combined with tobacco auctioneer Speedy Rigg’s cacophonous chants drove radio listeners crazy.80

In 1943, radio producer Dan Golenpaul, whose urbane quiz-show-cum-panel discussion program Information Please was rather incongruously sponsored by Lucky Strike, actually sued American Tobacco to try to stop the outrageous advertising campaign Hill demanded be run during the program. Lucky’s announcer had been barking “The best tunes of all move to Carnegie Hall!” as many as nine times during the half hour. Variety reported that Hill adamantly “held to his philosophy that it doesn’t matter how much you irritate the listener, so long as he remembers the slogan and the name of the product.” Golenpaul was unsuccessful in court, but Hill did agree to let Information Please out of its contract and find another sponsor.

American Tobacco gambled when they assumed the huge expense of sponsoring Jack Benny’s radio program in fall 1944. They were switching from purchasing spot advertising across many stations, times, and programs, to longer-term sponsorship of a major program, and concentrating about $3.9 million (or 80 percent) of their $5 million radio advertising budget into one program.81 At the same time, there was a cigarette shortage, which reduced company income.82 “We haven’t anything to sell, so why spend millions in advertising?” Hill complained.83 The shortage of Pall Mall cigarettes drove Hill to suddenly switch Benny’s sponsorship over to Lucky Strikes in August 1944, before the new fall radio schedule started.84

Frankly, American Tobacco needed Jack Benny’s radio program for its advertising strategies—a top rated and very respected show, light and humorous and Benny’s reputation for making advertising more congenial and would help soften complaints in the 1940s about Lucky’s advertising excesses. Cigarette manufacturers, trying to expand their sales and fight off the growing bad public relations of mounting evidence of links between cancer and smoking, paid for advanced research studies that analyzed smokers’ psychological motivations and satisfactions. Historian Richard Pollay reports that one study concluded that “Advertising makes cigarettes respectable, and is thus reassuring.” How could someone as wholesome as Benny be connected to something unhealthy? Variety reports suggested that Benny’s popularity with young people was a draw for American Tobacco, but they warned that use of Benny might set off criticism of having a pied piper advertise cigarettes to children.85

Reviewing Benny’s first broadcast for Lucky Strike in October 1944, Variety speculated on how Benny, his writers, and his cast might apply the Jell-O advertising “magic” to this differing sales situation, wondering “just how Don Wilson, who built up those Jell-O and Grape Nuts commercials into an integral part of the Benny comedy package, will tie in with the Lucky Strike format, in view of the standard auctioneering plugs?” Wilson’s role was indeed usurped by long opening and closing commercials in which Basil Rysdale hammered home repeated sales points and Speedy Riggs chanted. Wilson now introduced Jack and made various quips about the brand.

The plot of Benny’s opening Lucky Strike episode, of Benny vying with Fred Allen to impress a terrifying new sponsor (creating a fictional G. W. Hill character) was one of the strongest episodes that Benny’s writers had created in several years. “Benny has again firmly entrenched himself,” Variety marveled. “It’s a safe bet his followers aren’t going to desert him. And if the first show did something else. It unquestionably identified him with his new boss.”86 Critics who hated Hill’s advertising tactics speculated on Benny’s ability to stem or compromise the flow of irritating ads, and what manner of compromises the cacophony would make to the program’s comedy. A reviewer in Woman’s Day noted:

Such jokes as “With men who know comedians best, its Benny two to one” have helped to take the curse off the auctioneers, LS/MFT, chartering telegraph keys and the rest of the Lucky Strike nonsense. I’m afraid, however, that it was a question of give and take between Mr. Benny and the sponsor. Certainly, to open the show with a couple of minutes of commercial junk before Benny comes on is exceptionally bad programming. And I’ll bet Benny’s toupee is several shades whiter for it. Jack probably gave way on this point, though, to gain the end that he could, later on in the show, poke fun at the sacred advertising cows.87

Just two weeks later, however, Benny and his radio crew brought down Hill’s wrath upon themselves. The entertainment portion of the program ran over time and they missed broadcasting the closing commercial.88 Variety’s radio columnist Jack Hellman gossiped that

GW Hill was said to have hit the ceiling and an agency account exec lost his job over it. Whether Don Stauffer, radio head of Ruthraff & Ryan, made that quickie out here from New York to impress on Benny the importance of LS/MFT is conjectural. . . . We’re not insinuating that Mr. Hill scared Benny with his ceiling-hitting but what we do know is that the next week the program was short so there was plenty of time for the final LS/MFT and a bumper crop of theme [music].89

Stauffer returned to Hill’s office in New York with Benny’s deepest apologies. Hill wrote to Benny:

Mr. Stauffer said you wanted me to know what you were going to do, to wit: Sell LUCKY STRIKE cigarettes. . . . I am even salesman enough myself to know that it’s the year’s record that counts, not the individual black day from which we courageously attack our problem the day after. But I don’t have to wait this time for the year’s record, three shows are enough to convince me that you are going to sell the goods.

THE SPORTSMEN QUARTET’S MANIC MUSICAL

COMMERCIALS

And thus it went for two years. The next chapter details the general malaise that affected Benny’s show during the latter half of the war, as he lost writers and cast members to the draft, and the scripts became dull. The obnoxious Lucky Strike ads did not help. During the first two years of the Benny show’s Lucky Strike sponsorship, Don Wilson no longer provided the opening and closing commercials. His role was reduced to introducing Jack and then making some light-hearted references to Lucky Strikes and its ad slogans during the program. For the start of the fall 1946 season, however, in a renewed spirit of program innovation, Benny planned an experiment to bring a novel softer sell approach to the middle advertisements. G. W. Hill died of a sudden heart attack in September 1946, but to his credit, he must have approved Benny’s invention—or Benny, his writers, and musical arranger worked with lightning speed after the funeral.

The September 29, 1946, program had Don Wilson introduce Jack to a group of four male singers, the Sportsmen Quartet, who hummed but never spoke a word of dialogue. Their job would be to sing adaptations of popular songs that incorporated Lucky Strike advertising slogans into the lyrics. Like so many characters in the Benny world, the Sportsmen proceeded to drive Jack nuts by quickly spiraling out of control, spinning their tunes faster and faster, dissolving into a cacophony of LSMFT and Indian war whoops that caused Jack to scream to get them to stop. Although Benny later reminisced that he intended the group to only be on the program a few times, the huge positive critical and popular reaction to the Sportsmen moved Benny and his writers to build the group into regular characters.

The Sportsmen Quartet and their antic, hilarious middle commercials were the hit of a new prime time radio season that otherwise was mired in stagnation and sameness. Now Don Wilson “managed” the Sportsmen Quartet. Benny’s manager Irving Fein praised Don’s contributions to the comic byplay:

Don was a great foil for Jack. He was the hearty announcer who tried to get the commercial on the air and Jack would try to thwart him. Sometimes Don would have the Sportsmen Quartet sneak in the commercial. Don would tell Jack the Sportsmen were going to do a song. Then they would sing a chorus of a song. Don would then tell Jack they had one more chorus—and they would sing the commercial.90

Variety’s Jack Hellman called the humming, singing, wildly antic Sportsmen “the most novel innovation of the new season. It has caught on so well that radio editors around the country are playing it up.” Hellman snarkily gossiped that American Tobacco’s in-house advertising department was a little miffed at the attention Benny’s marketing efforts were getting.91 The ads also upended NBC bureaucrats, as Hellman noted that the cheeky song parodies were “the bane of network vigilantes” who had difficulty ascertaining where the entertainment ended and the advertising began.92 Sponsor chortled that the Sportsmen not only softened criticism of Lucky’s obnoxious advertising, but helped the bottom line—“Even the number one exponent of irritant advertising copy, the American Tobacco Company, has recently discovered that the amusing nonirritant middle commercial on the Jack Benny program was doing a much better selling job than the straight rubs-the-wrong -way approach.”93

The Sportsmen’s singing commercials became as subversive and amusingly outrageous as Benny’s earliest Canada Dry ads. When the Sportsmen sang the words of American Tobacco’s advertising jargon, Lucky Strike’s endlessly repeated ad slogans “LSMFT,” “so round and firm and fully packed, so free and easy on the draw,” “never a rough puff,” “quality of product is essential to continuing success,” or “Lucky Strike means fine tobacco” seemed to lose any kind of meaning and became totally absurd gibberish. All the silliness, and the Sportsmen’s manic performances, could have worked, for some listeners at least, to make the brand, the company and the whole idea of smoking ridiculous, and to cast a cynical suggestion that all of consumer culture could be absurd.

When Jack was sick at home in bed with a cold, the Sportsmen telephoned to cheer him with a version of “Button Up your Overcoat”:

Button up your overcoat

When the wind is free

Take good care of yourself

Careful, Mr. B.

Eat an apple every day

Go to bed by three

Take good care of yourself

Passing NBC.

Be careful in the breeze (ooh ooh)

Watch it please (ooh ooh)

Or you’ll sneeze (ooh ooh)

You’ll get a cold and ruin your program

If you’re really feeling bad

Call a doctor, too

Take good care of yourself

’Cause we all love you.

When you’re buying cigarettes

Buy the brand you like

Take good care of yourself

Smoke a Lucky Strike

When you’re driving in a car

Or you’re on a hike

Smoke a Lucky Strike

If I may have my say (Please do)

Don’t delay (what’s new)

Start today (ooh ooh)

Light up a Lucky and you’ll enjoy it

Men who know tobacco best

Smoke the best you see

Round, firm, fully packed

L S M F T94

The Sportsmen performed their version of “Deep in the Heart of Texas”95 at Jack’s house, where he was getting a rub down from his masseur Mr. Nelson (Frank Nelson, who always played devilishly annoying characters). The hearty handclapping that accompanied the song was merged with Nelson slapping Benny’s behind in time to the music, and Jack yelping:

The smoke they like, is Lucky Strike (clap clap clap clap)

Deep in the heart of Texas

Throughout the state, they say they’re great (clap clap clap clap)

(Benny—ouch!)

Its Lucky Strike in Texas

They like the pack, of fine Toback (clap clap clap clap)

(Benny—Mr. Nelson! Not so hard!)

Now you’ll be smoking Luckies

In cattle land, the favorite brand (clap clap clap clap)

(Benny—you’re hurting me!)

Is better tasting Luckies

Not only did the Sportsmen sing arrangements of popular standards, but they tackled operatic music, bringing in a famous soprano with the Metropolitan Opera, Dorothy Kirsten, to sing the Quartet from Rigoletto with the fellows. And Benny joined them on his whining violin for particularly manic versions of such classics as the “Anvil Chorus” from Il Trovatore, Mendelsohn’s “Spring Song,” the Poet and Peasant Overture, and the “Saber Dance.”96 The Sportsmen’s song parodies were written by Benny’s music arranger Mahlon Merrick, and the lines had to successfully gain the approval of the network, advertising agency, and the sponsor. American Tobacco may have determined that these humorous assaults might deflect some of the growing public concerns over tobacco and health issues. The product was a declining brand in the 1950s, as younger smokers preferred the new filtered tip cigarettes. Lucky Strike’s manufacturer still needed to spend money on advertising to keep its older customers loyal to the brand, nevertheless, so they continued to sponsor Jack Benny’s television program through June 1959.

• • •