Procrastination can be puzzling. This variable and complex process comes with lists of causes, symptoms, jokes, and horror stories. It can range from sporadic to persistent. It can be obvious or arrive in disguise. In this chapter, you’ll begin to see procrastination from different angles and learn to adjust your level of aspiration concerning the time and resources you will need if you are to take corrective action against procrastination.

It’s important to recognize that awareness is the very first step in identifying procrastination traps in order to make positive changes that can overcome the procrastination habit. However, as Alfred Korzybski, founder of General Semantics (an educational discipline on the accurate use of words), said, “The map is not the same as the territory. It’s a symbol and guide. You learn the territory by engaging the process.” So let’s get started!

Procrastination is a needless delay of a timely and relevant activity. This definition applies across situations ranging from returning a phone call to creating a business plan to quitting smoking.

Occasional procrastination delays in areas of your life that are of relatively low importance are not the end of the world. If you normally shop for groceries once a week and you put off shopping for a day, this procrastination act is inconsequential. However, persistently putting off a number of minor and middle-valued activities is self-defeating if you routinely feel swamped by things you delayed yesterday.

Regardless of whether your procrastination is erratic or persistent, taking action to stop procrastination habits or patterns can lift artificial limits that you previously placed on your life. Any area of procrastination is grist for the mill for purposes of teaching yourself to rid yourself of the procrastination act on the way to disabling the pattern. This is a radically different way of thinking from that of time management hawks, whose views are calculated to get people to work harder and to put out more under umbrella terms of working smarter and easier.

Some causes of procrastination are social, some are linked to brain processes, and others are belief-driven or reliant on temperament and mood. Some forms of procrastination can also be connected to anxiety—feeling uncomfortable about being judged or evaluated. Combinations of motives for procrastination tend to vary in each individual situation. However, it is both the consistency of the procrastination process and the great diversity in situations that set procrastination apart from conditions. A cued panic reaction normally takes far less time and effort to change than a broad pattern of procrastination that may show up in different venues and in surprising and unexpected ways. Let’s take a look at general forms of procrastination.

Deadlines have an endpoint and are partially connected to some sort of rule or regulation that you often can’t control but that requires your compliance. When you think of procrastination, you may think of missing deadlines or rushing to meet them. That’s a common view of procrastination. Not surprisingly, deadline procrastination is the act of waiting as long as possible before taking action to meet a deadline.

Work life is ruled by timelines, processes, and deadlines. Let’s say you are working on your company’s semiannual advertising brochure. To get it out at the appointed time, you’ll need to take certain steps, such as preparing the content and design, getting it printed, and getting it distributed, in accordance with a schedule. If these activities were not regulated, the advertising brochure might be completed in a disorganized manner.

When a timeline and instructions are fuzzy, but the deadline is clear, you have a special challenge. You may see tasks with vague instructions as something to do later. When a task’s purpose and instructions are clear and concrete (when, where, and how), you are more likely to do it. Thus, if you are not sure, ask. And if there is no clear structure, invent one!

You may have a deadline for a long and complex project, and the only reward in sight is the relief you expect to feel when it’s done. In this case, you may face another set of challenges that has to do with the distance from your internal reward system. Pigeons will work for small immediate rewards but slack off for a larger reward that requires more work. Monkeys will get distracted and procrastinate when the reward is too far in the distance. We’re not far from our mammalian roots when it comes to putting something off when the reward is distant and requires a lot of work. Humans will tend to go for quick rewards and discount bigger future rewards. We’ll tend to delay starting projects that appear complex or ambiguous, or that promote uncertainty. Conflicts between our primitive impulses to avoid discomfort over complexity and our higher cognitive functions to solve problems can interfere with rational decision making and promote delays. Thus, a complex long-term project may be like the perfect storm unless you do something else first.

Deadline situations are often trade-off situations. If you want to get a paycheck, you follow the organization’s processes and schedule and avoid procrastinating. The organization gets what it wants, which is a work product, and you get what you want, which is payment for your services. When you have a deadline in the future and the project is complex and requires consistent work, you may have no alternative other than to start early and invest significant time and effort in the process. If the process is internally rewarding, then that may suffice. Otherwise, you’d wisely set periodic rewards following intermediate deadlines that you set for yourself following the completion of predefined chunks of work.

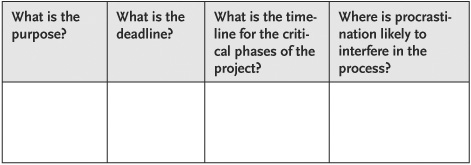

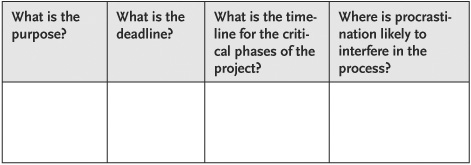

If procrastination interferes with a productive long-term work process, a chart reminder may help you keep perspective on the purpose, deadline, timeline, and procrastination risk factor:

Remember, being aware and cognizant of your procrastination habit is the first step in our three-pronged cognitive, emotive, and behavioral approach to defeat procrastination. Reminders can be helpful. Human memory is fallible. Some delays are due to forget-fulness. You can meet some deadlines automatically with mechanical processes, like automatic payments to utility companies and mortgage holders, that eliminate work. This is also an efficient thing to do. You can use tickler files, calendar notations, iPhones, PDAs, and your cell phone to remind you of important dates.

Deadline procrastination is just the tip of the procrastination iceberg. A bigger and more serious challenge may involve personal procrastination. Personal procrastination is habitually putting off personally relevant activities, such as facing a needless inhibiting fear. You stick with a stressful job that you want to ditch. You feel timid, and you promise yourself that you’ll take an assertiveness class someday. Instead of engaging in self-improvement activities, you watch TV and read tabloid magazines.

Because self-development activities are just about you, and because they are open-ended with an indefinite start date, this may not seem like procrastination. However, it meets the definition. The following chart is a classic framework for identifying your top self-development priority. The process involves defining your most pressing and important self-development goal or priority and other activities that are worth pursuing. Engaging in activities that are not important and nonpressing before all the activities above them are done may waste your time and resources. If you emphasize not important and nonpressing activities over your number one priority, you’re procrastinating by using the bottom-drawer activities as diversions. For example, if you face a health risk and you read Hollywood scandal magazines in lieu of taking steps to stop smoking, you need to think about what you’re doing. The following chart is an example.

Now it’s your turn to define what are the most pressing and important things for you to do.

Omissions. What you omit doing may be a prime area of personal procrastination. Dick was retired and spent a great deal of his time complaining. He complained about his woman friend and how her ongoing misery and physical complaints affected his mood. He complained about his breakfast group, whom he saw as the cold blanket squad who complained about their aches and pains and the importance of maintaining the status quo. He complained about lost opportunities and the hassles of life. What did these complaints have in common? They were all diversions.

Dick’s pressing and important and nonpressing and not important self-development chart helped him isolate several areas of procrastination. First and foremost, he wanted to learn how to do teleconferencing on his computer so that he could keep in direct contact with his children and grandchildren. He wanted to visit art centers, travel, and study politics. His complaints covered up what he did with his time, which was mostly sleeping during the daytime and watching television at night. Once we established his priorities and identified the futility of complaining, then Dick started to work on his personal development challenges, which were no longer mysterious.

Simple procrastination is a default procrastination style in which you resist and recoil from any uncomplicated activity that you find mildly inconvenient or unpleasant. This may start with a momentary hesitation that, unless it is quickly overridden by a productive action, may trigger a procrastination default reaction. This hesitation process may have to do with the way the brain works.

The brain may be wired to promote a later factor, or an automatic slowing in decision making: the time it takes the brain to voluntarily react to a sensory signal is longer than expected. This may be a result of decision-making and delay issues caused by your higher mental processes having difficulty understanding the signals from lower brain functions. The potential conflict between lower brain processes and cognitive decision-making processes may partially explain how a simple procrastination default reaction starts. If you have a discomfort sensitivity triggered by this conflict, and then you extend the delay to the level of procrastination, the later factor suggests a possible mechanism. But whether this is the real mechanism or the reaction is caused by something else, the solution remains the same. You have to act to override this biological resistance.

When procrastination includes coexisting conditions, it’s complex. Complex procrastination is the kind of procrastination that is accompanied by other factors, such as self-doubts or perfectionism. Complex procrastination is a laminated variety. You can separate the layers and address each as a subissue. However, the layers tend to be interconnected, so by addressing one layer, you may weaken the connection with the others. For example, let’s say you have an urge to engage in diversionary activities. You switch to doing something trivial, perhaps something more costly. You need to pay a bill, but instead, you go to a casino to gamble. You then try to forget your new gambling debts by turning on the TV.

When you face and overcome coexisting conditions, your goal of cutting back on procrastination doesn’t go away. You may have eliminated one of the complex layers; however, procrastination often has a life of its own and goes on as it did before. You still have to deal with your procrastination habit if you want to free yourself from this burden by changing procrastination thinking, developing emotional tolerance, and behaviorally pursuing productive goals.

Procrastination can be a symptom, a defense, a problem habit, or a combination of these general conditions. It can be a symptom of a complex form of procrastination, such as worrying about worry and then putting off learning cognitive coping skills to defuse the worry. Busywork can be a symptom of underlying tension for a problem that you want to avoid. This busyness is a kind of behavioral diversion, which is as productive as racing down a dead-end street.

A procrastination symptom can be especially helpful when it provides cues about an omission that needs recognizing and correcting. For example, the English naturalist Charles Darwin put off his medical studies and eventually came up with a theory of evolution by following his real passion. His symptom was his distraction from his medical school studies. Let’s say your family persuades you to run the family sporting goods store. You have limited interest in managing the store, but you do so out of duty. Procrastination surfaces when it comes time to order new goods, keep up with paperwork, and deal with personnel matters, but you are quick and efficient in making better use of existing shelf space, creating an attractive façade, and landscaping, because what you really want to do is study architecture. What you emphasize in your work is a testament to your personal interest.

Procrastination can be a defense against conditions, such as fear of failure, failure anxiety, and fear of blame. If you tend to think in a perfectionistic way and you believe that you cannot succeed at the level at which you think that you should, this may trigger procrastination by causing you to exert only halfhearted efforts or to decide to do something else altogether. If you focus on the horrors of failure, you may omit looking at a probable mechanism, such as perfectionist beliefs. Fear of success is another form of failure anxiety that can have the same impact as fear of failure. You believe that if you succeed, the pressure for you to do more will increase. In this frame of mind, it is easier to delay now than to risk failure later. You have other ways to construe these possibilities. Putting off thinking about these evaluative fears, and taking possible countermeasures, is a form of conceptual procrastination.

You can gain control over the causes of procrastination by addressing them. However, an automatic procrastination habit may remain, and you may continue to have an automatic urge to procrastinate.

Habits, even procrastination habits, may operate blindly when they serve no useful purpose. To respond to an automatic procrastination habit, plan on overpracticing your counter-procrastination strategy to weaken the strength of this automatic habit.

Procrastination is normally a complex problem process. Separating procrastination into the three categories of symptom, defense, and problem habit gives you a way to frame what is going on when you procrastinate. A good assessment for complex procrastination can point to change techniques that you may find useful. When you target potential underlying mechanisms for procrastination, you can more accurately target corrective efforts that fit the problem or recognize potentially effective actions through your own readings and research.

Procrastination comes about for different reasons. Like clothing, it comes in different styles. If you know your procrastination style(s), you can mate your corrective efforts to it. This is a big benefit. When you carefully target your corrective actions, you are less likely to go down dead-end streets or invest time in diversions that you may mistake for interventions. Lying on an analyst’s couch to free-associate about early childhood issues about procrastination can be a diversion. Table 1.1 describes a sample of procrastination styles and corrective actions.

TABLE 1.1

Procrastination Styles and Corrective Actions

Procrastination styles may surface in different contexts and have some unique twists. However, the underlying procrastination processes are roughly comparable. Thus, when you understand this underlying process, you can use this knowledge to address procrastination across a variety of contexts and styles.

Acknowledging a procrastination habit is a critical step on the path to change. Having some preexisting knowledge of what lies on the path is better yet. You’ll know where to look and what to target. Even if you don’t have an interest in tackling procrastination now, understanding how the process works may later lead you to experiment with counter-procrastination ideas and techniques.

Moving from a procrastination path to a productive one often starts with a shift from feeling absorbed in procrastination process thinking, feeling, and behaving to a self-observant problem-solving perspective. When you are self-absorbed, you draw inward. You’re concerned about how you feel, how you might look to others, or whether you are perfect enough. When you are absorbed in such anxious thoughts and feelings, you may find it hard to keep your productive goals in focus. Procrastination thoughts may linger as you languish. This inward view finds outward expression in procrastination.

A self-observant way of knowing and doing involves a radical shift from an inward to a reality perspective that is elegant in its simplicity:

1. Monitor your thoughts, feelings, and actions and do a perception check.

2. Take a scientific approach, in which you rely on observation and draw evidence-based inferences and conclusions.

3. Predict the outcome of playing out different scenarios.

4. Act rationally to achieve enlightened positive goals.

5. Learn from planned procrastination countermeasures and apply new learning.

On a case-by-case basis, you can make a radical shift from a self-absorbent to a self-observant perspective. Unlike learning to read, where it takes several years to get the basics and to build from there, you can start this shift right away. However, progressive mastery of procrastination is a process that extends over a lifetime but gets simpler and easier in time. As the rewards for your self-observant efforts pile up, you’ll have added incentive to continue in this do-it-now way.

A procrastination log is an awareness tool for tracking what you do when you procrastinate. Logging what you think, how you feel, and what you do as you procrastinate promotes metacognitive awareness. This is your ability to think about your thinking and to make connections between your thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and results. If you prefer a more freewheeling style, create a narrative in which you log an ongoing commentary of what is happening when you procrastinate.

When you have an impulse to delay, start recording and logging what you tell yourself and how you feel. Note the diversionary actions that you take. If you are unable to make immediate recordings, record procrastination events as soon as you are able to do so, and be as concrete and specific as you can about what you recall observing.

You may find it equally important to record what you think, feel, and do when you follow through. What can you learn from your follow-through actions that you can apply to procrastination situations?

By nailing down what goes on when you procrastinate, you put yourself in the catbird seat to understand the process and disrupt it with a do-it-now alternative action. However, personal change is ordinarily a process, not an event. It takes experimenting and time to test and integrate new self-observant ways of thinking, feeling, and doing. The new habits will compete with a practiced self-absorbent procrastination style that may carry on as though it had a life of its own. However, once you are into a process of change, you may find building on the process easier and simpler.

The five phases of the change process are awareness, action, accommodation, acceptance, and actualization. I first used this structure for change in my early seminars and group counseling sessions with people who wanted to stop procrastinating. The process assumes a self-observant perspective. It is a way to organize a counter-procrastination program into a powerful process.

In this dynamic system for change, the different phases interact. The priority ordering may change. Action may lead to insightful awareness. Accommodation includes seeing incongruities and contradictions and adjusting to reality. Acceptance may make it easier to experiment with new ideas and behaviors. In actualization, you stretch to discover your boundaries, and you may find that you broaden those boundaries the more you stretch. This knowledge adds to a growing awareness of what you can accomplish through your self-regulated efforts. The following describes how the process works.

Awareness is listed as the first phase of change. You intentionally work to sharpen your conscious perspective on what is taking place within and around you during procrastination and do-it-now approaches to problems. You apply what you learned about making a radical shift from a self-absorbent to a self-observant perspective. You think about your thinking. You make your goals clear to yourself. As a means of self-discovery through productive efforts, you guide your actions through self-regulatory thoughts to discover what you can do to reduce procrastination by increasing your efforts to promote productive actions.

Positive Actions for Change. On a situation-by-situation basis, map and track what you do when you procrastinate. Identify what is similar and what is different from situation to situation. Connect the dots between do-it-now activities and procrastination and outcome factors. These may include type and quality of accomplishment. Ask yourself the following questions:

• What type of stress do you experience when you are in a do-it-now mode of operating? (This usually involves a productive form of stress, or p-stress.)

• What type of stress do you experience the longer you put off a pressing and important activity? (Procrastination tends to be coupled with various forms of distress, or d-stress.) What do you conclude from this information?

Action is your experimental component for change. You actively test ideas to see what you can do to promote visible products from your work efforts and conceptual and emotional changes from reflecting on the process that you used to produce positive results. In this stepping-stone phase, you put one foot in front of the other to test your ideas against reality. While words in books on how to drive a car can tell you what to do, really learning to do starts by getting behind the wheel. You may never be a perfect driver, but through practice and experience, you can develop the skill to be a competent driver. Conquering procrastination starts in a similar way. You may never be perfectly productive, but you can be competent in the area of self-learning and development. By initiating concrete actions, you are likely to gain productive ground.

Positive Actions for Change. Awareness is the first step listed. However, it isn’t necessarily the first step to take. By accidental discovery, an action can prompt a new awareness. You can enter the process of change at any point, such as experimenting with do-it-now actions to see what you can learn about yourself as the agent of change in this process. Advance the nonfailure concept from the Introduction by framing proposed actions as hypotheses. Like a scientist, you test whether an action you have decided on will promote a desired outcome.

• Make a contract with yourself to perform prescribed steps to introduce a change in the procrastination process. Instead of following an urge to diverge, live with the urge for five minutes and observe what happens. What did you learn?

• After examining the urge for five minutes, act to follow do-it-now steps. What happened? What did you learn?

Accommodation is the cognitive integration phase of change. It’s my favorite part of the process. Here you play with juxtapositions, incongruities, and paradoxes between productive and procrastination points of view. For example, tomorrow views and do-it-now views have many contradictions. You don’t do it now tomorrow.

Positive Actions for Change. Accommodating new ways of thinking, feeling, and acting first involves testing new feelings, thoughts, and actions. It normally takes a while for the brain to adjust to new ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving.

• Contrast procrastination and do-it-now views. What do you gain by thinking that later is better? What do you gain by following a do-it-now path? What makes later seem so hopeful when reality tells a different story?

• Is it possible to change procrastination goals to avoid effort and work to productive goals? Can the productive goal include observing a strong procrastination process to identify its weaknesses and vulnerabilities?

• Can you convert complaints that support procrastination to positive goals? For example, “This is too complicated for me” may be converted to “I can handle the first step.” If you first see an action as too complicated, yet you can handle the first step, you’ve found a procrastination paradox.

• If you tell yourself that you work better under pressure, why not plan to put something off until the very last minute? If you tell yourself that you work better under pressure and then swear that you won’t put yourself through this type of emotional wringer again, can you have it both ways?

• What might you learn by locating and examining procrastination paradoxes? An example of a procrastination paradox is that you work better under pressure, yet you want to work smarter next time by starting earlier. The odds are that you don’t work better under pressure; rather, you are more likely to start when you feel pressured.

Acceptance is the phase of change in which you take reality for what it is, not what you think it ought to be. Acceptance supports tolerance, and this frees up energy that is ordinarily sopped up by blame and doubts and beliefs that promote fears. Acceptance is cognitive, but it is also an emotional integration phase of change. Acceptance has a quieting effect, but also a positive energizing effect when you translate this view into a willingness to experiment and satisfy your curiosity about how far you can stretch and grow.

Positive Actions for Change. Acceptance involves the recognition of variability. What parts of your life are working well, and what have you done to establish that state? In what phases of your life do you fall short of ably regulating your actions? Is it possible for you to accept this state and still consider productive actions to improve your condition? Ask yourself these additional questions:

• If you procrastinate, so be it. Now, what can you do to change the pattern and get better if you choose to do so?

• Do you live in a pluralistic world that involves adaptability to different situations or a world in which a systematic and procedural approach and scheduling resolve all difficulties? Is there room for both views?

• What have you learned from considering this emotional integration phase of change?

END PROCRASTINATION NOW! TIP

The CHANGE Plan

Conquer a procrastination challenge by breaking it down to manageable parts.

Hang in with your positive do-it-now plan until it becomes automatic.

Adapt to altering conditions while keeping your eye on opportunities to follow a do-it-now plan.

Negate distractions by acting on what is most important and pressing to do.

Gain from the experience by reviewing what you did well that you can repeat.

Envision your next do-it-now steps to move forward to achieve new productive goals.

Actualization is often portrayed as a mysterious process in which you have oceanic or peak experiences. It may be a Buddha-like desireless state. It may be a state of mind in which you experience a conceptual and emotional sense of connectedness with all of humanity across cultures, time, and dimension. You can also view actualization as stretching your abilities and resources enough to promote meaningful changes in your life in those areas where such efforts are meaningful and important. That’s how I prefer to use the concept.

Positive Actions for Change. Follow-through is to actualization as water is to plant growth. What actions can you take to rescript your life narrative to include the results of experiments in stretching to find the boundaries of what you are able to accomplish that you’d value? Additional questions to ask yourself are:

• What ideas or actions have you found effective in one phase or zone of your life that you can apply to procrastination zones where you are experiencing stagnation?

• Does organizing and regulating your ideas and actions promote stretching and accomplishing?

• What do you learn about yourself by taking a few extra steps to stretch in the direction of actualization?

Change can be something you just do. Let’s say you want to alter your appearance to initiate change, or maybe you’d like to take a vacation for a change. But some changes take time and a process that can compete with an old habit that you wish to change.

Changing from a pattern of delays to a productive pattern is rarely a finger-snapping act. Getting yourself disentangled from the cognitive, emotive, and behavioral dimensions of procrastination typically takes a process of pitting reason against the unreason of procrastination thinking, learning to tolerate tension without easily giving in to urges to diverge, and establishing behavioral patterns where you act against behavioral diversions by engaging in productive actions.

In working through this process—and as you practice, practice, practice—there will come a time when you’ll find yourself shifting your efforts into productive pursuits as automatically as you once avoided many of them. You can apply the five phases of change again and again to help promote that outcome.

The French psychologist and educator Jules Payot thought, “The aim of the great majority is to get through life with the least possible outlay of thought.” If you want to differentiate yourself from others immediately, start a course of voluntary change in which you reach out and expand your capabilities to overcome procrastination!

Voluntary actions for personal change may be among the challenging variety. That’s because there may not be a clear starting point. There are no deadlines because the change is an ongoing lifetime process. The process involves self-observant directed effort. This effort is a necessary step. Have you ever accomplished something of merit without effort? It is your turn next to test the process to see if you can change procrastination events:

Positive Change Actions |

Awareness: |

Action: |

Accommodation: |

Acceptance: |

Actualization: |

Mythologist and Columbia University Professor Joseph Campbell saw this pattern in tales of heroes. There is a challenge. An ally fills in information. The hero discovers how to apply the knowledge. Are you up to the challenge?

Change, even the most positive kind, normally involves periods of adjustment and accompanying stress. When you anticipate changing a practiced routine, this anticipation can evoke stress. You might procrastinate. If you view some discomfort as a natural part of life and change, you are more likely to progress.

What three ideas for dealing effectively with procrastination have you had? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.

What are the top three actions that you can take to shift from procrastination toward productive action? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.

What things have you done to execute your action plan? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.

What things did you learn from applying your ideas and action plan that you can use? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.