Aconscious decision to act decisively is the first step in initiating behavioral follow-through. Once you’ve become aware of triggers that cause habitual procrastination, you’ve emotionally coped with the unpleasant task, you’ve made an active decision to get the task done, and you actively follow through, then you’ve stopped your procrastination cycle. Overcoming indecision is a key part of this positive change process, and you’ll learn how to get off the fence and follow through with what is important for you to do.

The fourth-century Chinese general Sun Tzu stated that if you know your enemy and yourself, there is no need to fear the results of 100 battles. Sun Tzu’s statement refers to decision making as well as to war. If you know why you put off major decisions, know how to make reasoned ones that work for you, and then persist in following through, you’ve ended procrastination. That won’t happen 100 percent of the time, any more than winning all battles is a realistic option. However, you can load the dice in your favor, and you can learn to do that here.

Decision making is an ongoing part of being human. What makes for a good decision? How do you get to that point? Unfortunately, there are no guaranteed guidelines on how to make decisions. Decision-making situations vary widely. Different situations may require you to apply different values, rules, or procedures. Some decisions involve resolving conflicts. Others contain opportunities, but also risks and uncertainties. The options you face can include tough choices. You may have unwanted trade-offs and lesser-of-evils choices. You may experience conflict between giving up a great opportunity that’s out of reach and choosing one that is attainable, but of lesser value. An ideology or bias can influence the direction of the decision unfavorably. Knowing yourself, then, is important in decision making.

How do you improve the quality and timeliness of your decisions when procrastination interferes? In this two-stage process, you learn to get out of a decision-making procrastination holding pattern and act to make and execute purposeful and productive decisions.

To advance this two-stage process, I organized this chapter into three parts. The first describes factors that are involved in indecision. The second is about ending decision-making procrastination. The third discusses how to make and carry out productive decisions.

The Latin word decido is the root of decision. It has two meanings: to decide, and also to fall off. To avoid a fall, you may decide not to decide. However, if you’ve adopted the no-failure plan from earlier in this book, and you emphasize discovery over blame avoidance, “falling” like an autumn leave is not an option.

In this section, let’s look at uncertainty as a condition for indecisiveness. It discusses four ways to overcome decision-making procrastination, avoid needless pain from sitting on a spiked fence, and act to secure useful gains.

In ambiguous situations you don’t see the full picture. You are aware that you face unknowns. You have no guarantee of success regardless of what you do. When you feel unsure and doubtful, you may avoid making a decision even when managing the uncertainty is a pressing priority.

Uncertainty may stimulate doubts, challenge, or something in between. However, is a high-priority situation with unknowns automatically a cause for stress and procrastination? It depends on how you define the situation and your tolerance for uncertainty.

If you are among the millions who are intolerant of uncertainty, you may find this intolerance rooted in a highly evaluative process. For example, oversensitivity to discomfort plus either exaggerating and dramatizing the dreadfulness of the situation or seeing it as being as bad as, if not worse than, it can possibly be amplifies the tension. Under these amplified stress conditions, it is understandable that a procrastination path of least resistance can seem appealing.

Let’s look at four conditions associated with intolerance for uncertainty and procrastination: illusions, heuristics, worry, and equivocation.

Your intuition, insightfulness, and emotional sensitivity were present before your reason developed. The evolution of reason and foresight opened opportunities to go beyond survival to higher-level choices and decisions. However, a tool that is an asset can also be a liability.

A psychological illusion is a blend of intuition and false thinking. It is something that you believe is real and true, but that in fact isn’t the way you perceive or read it. Psychological illusions can and do arise as answers for reducing uncertainty.

Do you believe that you make illusion-based decisions that can give you a false sense of clarity, but also a high decision error rate? Few people believe that illusions have a controlling influence over their lives. But illusions often interfere with identifying rational choices and deciding on what to do to best meet the challenge.

You probably have illusion hot spots that coexist with procrastination. Indeed, procrastination sometimes reflects the mind-fogging power of illusion. The tomorrow or mañana belief is an illusion of false hope. Believing that you can’t manage uncertainty can map into an illusion of inferiority. If you do not see your harmful psychological illusions, you are likely to repeat self-defeating patterns without knowing why.

If you act as though you think your assumptions are the same as facts, you may operate with an illusion of understanding. You can misread situations with confidence and make decisions based on this misreading. Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith noted that when people are the least sure, they tend to be the most dogmatic.

Here is a sample of illusions that taint decision making:

• Illusion of judgment. You believe that your judgments are invariably accurate. However, for this to be true, you would have to have the best of all authoritative information and be entirely objective and free from bias.

• Illusion of emotional insight. You assume that if you feel strongly about something, you must be right. Based on this supposed emotional insight, you are likely to judge on the basis of your first emotional impressions with very little else to go on.

• Illusion of superiority. You assume that you are smarter and more capable than anyone else. Thus, you automatically reject suggestions or alternative courses of action that are inconsistent with your own views.

• Illusion of inferiority. You underestimate your capabilities even when your actions show greater capabilities. When you limit yourself in order to maintain consistency with this view of yourself, you risk making it a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Here is a brief proactive coping exercise for addressing psychological illusions, making realistic decisions, and avoiding procrastinating on decision making.

In an unfamiliar situation, you may rely on heuristics, or examples, to guide your decisions. These rules of thumb, common sense, or selected tidbits or examples from experience take many forms. “When in doubt, flip a coin” is a heuristic.

Heuristics can map a path to better planning and decision making. You may profitably use a heuristic of mentally working back from a future time when you’ve achieved a goal. By reflecting on the steps you took, you may help yourself get past a planning bottleneck.

When there are gaps in your knowledge and you have virtually no time to study an issue, trusting your feelings may be the best thing to do. If something doesn’t feel right, it may not be right. You’re offered a deal that you have to decide on right away. It sounds too good to be true. You rely on emotional cues and past experience to assess the offer. You pass on the deal. However, some heuristics have a downside in that they lead to poor decisions, and some hide procrastination.

• Heuristics sometimes work well enough. However, rules of thumb can lead to distortions and bad decisions. You believe that someone who looks you straight in the eye is honest, but here is a paradox: pathological liars will normally look straight at you, whereas a shy but unusually honest person may avoid eye contact.

• The fundamental attribution error is among the best-validated heuristics. This is the tendency to see your own errors as situational and explainable. When observing the errors of others, however, you do the opposite: you downplay situational factors and attribute poor results to character flaws, such as “laziness.” This is part of a tendency to understand your own situation and exonerate yourself from blame, and then blame the other guy for actions that you wouldn’t blame yourself for if you were the actor. If you rely heavily on “gut” impressions, your decisions are likely to be arbitrary and biased. Saying that you rely on gut impressions is often a cover for expediency procrastination. When you rely on gut impressions, you don’t have to prepare and make a studied decision. Thus, relying on gut feelings can be unwise.

Heuristics are normally more efficient than the automatic reactions of perception, where a whisper of negative emotion is sufficient to trigger a procrastination sequence. However, because heuristics are blanket rules, they are normally inferior to a reasoned-out assessment. Here is a brief proactive coping approach for improving heuristic-biased decision making by adding some reflective components.

Awareness: Separate perceptual reactions from heuristics from reflective preparation. By doing so, you’ll know where you stand in decision-making situations. |

Action: Decide which of the different decision-making responses is appropriate for the situation. Does the urge to diverge fit with your longer-term objectives? Are the heuristics in this case free from realty-distorting bias? What does taking a studied approach offer? |

When you worry, you show intolerance for uncertainty. You fill in the gaps with assumptions about harmful possibilities. You tense yourself over threatening and catastrophic possibilities that you have no knowledge of actually happening.

This cognitive and emotional distraction may prompt procrastination.

Worry and procrastination share certain features. Both have a specious reward. When the catastrophic possibility doesn’t happen, you feel relieved. Relief is a reward for a worry where the dreaded results don’t happen. A decision to act later can feel relieving and rewarding. Relief is a reward when it increases the frequency of the act that it follows, making worry or procrastination, for instance, more likely to recur in similar circumstances.

Here is a brief proactive coping exercise for defusing worry-stimulated procrastination.

Awareness: If you worry too much about making wrong choices, you have a false belief(s) that underpin(s) worry. You may believe that you need certainty under uncertain conditions. |

Action: Beliefs are convictions, but conviction doesn’t make a belief true. To put matters into perspective, think about the best and worst things that can happen and many in-between results. Think about what you’d have to do to achieve each. What is the most probable outcome that you can control? |

If mulling over pros and cons puts you in a procrastination holding pattern, this equivocation can set the stage for a perfect cognitive, emotive, and behavioral storm for making an impulsive decision. For 15 years, Willow looked for her perfect soul mate. Equivocating over one potential mate after another, she couldn’t decide. As a skilled defect detector, she found flaws in everyone, angered herself over their imperfections, and eventually unceremoniously rejected all of them.

Then the time came when Willow’s biological clock was winding down. She singled out the issue of having babies, and that became her priority. Finding the perfect soul mate was no longer a priority. Marriage became the means to the end of having children. Tony, who had a serious alcohol addiction, was available. She impulsively married him. Two years and two kids later, an unemployed Tony has refused to stop drinking. Willow has another major decision to make, and she is uncertain what to do.

Here is a brief proactive coping exercise for addressing decision-making equivocation.

Awareness: It can seem as if you are going through an endless loop if you keep going over the same ground and adding conditions and qualifications. Equivocation, then, reflects a need for certainty. However, only the most relevant conditions need to be met. |

Action: Most decisions that include uncertainties carry a real possibility that the decision will be adequate but imperfect. Occam’s razor refers to the idea that conditions should not be needlessly made more complicated than they actually are, and that the simplest explanation is normally the best. Simplify. |

An automatic procrastination decision (APD) starts with a primitive perceptional whisper of emotion and an urge to diverge. APDs may come from subconscious causes, such as perceiving something in the situation as complex and unsettling.

A higher-order APD occurs when you make a promissory note to yourself to do later something that you can start now. This can trigger a chain of procrastination thoughts:

“I don’t know which action is the most important or where to begin. I’ll rest on it.”

“I need more references.”

“I need to read more before I can start.”

“I won’t be able to start today because there isn’t enough time.”

“I’ll get to it later.”

A false later is better decision can glide under the radar of reason. When that happens, more procrastination decisions may follow. You decide to coddle yourself by telling yourself, “I’m too tired to think.” If your performance is later diminished, you can excuse yourself because you were once fatigued. And when the time comes to decide again, you self-handicap yourself again to sanitize a delay.

Thinking about your thinking and connecting the dots between procrastination thinking and its consequences puts you in a better position to decide on a productive course or action, and this is often a first step in asserting control over the procrastination process.

APDs are a predictable part of lateness procrastination and other procrastination styles. Lateness procrastination is when you dabble with nonessential activities and keep dabbling past the time when you should get going to arrive at a destination. Dabbling, or doing such things as dusting, showering, or making phone calls, is your APD. In drifting procrastination, you routinely put off creating life objectives and bind yourself to a sense of purposelessness and APDs such as TV watching. Decision-making procrastination, like lateness and drifting procrastination, is a distinctive procrastination style. It also has APDs, but they occur in the context of avoiding decisions.

Decision-making procrastination is a process of needlessly postponing timely and important decisions until another day and time. You have a choice of relocating to Boston or Miami for your job. Both have roughly equivalent advantages and disadvantages. If you put off the decision until you come up with the perfect answer, you’ve entered the decision-making procrastination trap.

Let’s look at techniques and strategies for ending decision-making procrastination and building decision-making skills. These joint methods include singling out what is important, exercising a do-it-now alternative, following through with a rational decision process, strategic planning, and problem solving.

Making a decision based on two or three of the most important factors in a situation is rarely a waste of time. Then when you single out one choice from among others, you’ve made it the most important. Deciding can be as direct as that.

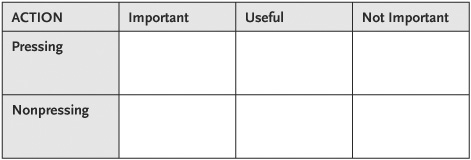

In a work world with multiple responsibilities and conflicting priorities, how do you know if you are on track with your main priority? You can use the following priority matrix to rank information from what is most pressing and important to your “not important” and “nonpressing” activities. This priority defining matrix approach is a classic type of time management technique that can aid in making decisions about what to emphasize; the most important and pressing activity obviously takes center stage.

If an activity is important but not pressing, and nothing else is higher on your list, this is an activity that you can start without feeling rushed. For example, you know that you have a distant deadline for consolidating and simplifying 12 different but related production forms into one page of information. Rather than straightening out your files (not important and nonpressing), you attack the consolidation project. You’ve created an opportunity to get this activity done before it rises to a pressing status. The matrix also helps you distinguish between a priority and a diversion. If you do nonpressing and nonimportant activities over the important and pressing ones, then you can assume that you are procrastinating on the priority.

Is it the situation or what you make of it that stirs anxiety over uncertainty that can lead to decision-making procrastination? The situation is the stimulus. It is not the cause. Rather, it’s both the situation and how you view it that influence what you decide. Your decision may also be affected by what you think about the process of executing the decision and the results you anticipate. These considerations can lead to dancing around a decision or moving directly toward making a choice and following through with action.

Although hesitation in uncertain situations is normal, hesitation plus procrastination suggests a complex form of procrastination. For example, feeling frozen by indecision is a probable symptom of anxiety over uncertainty.

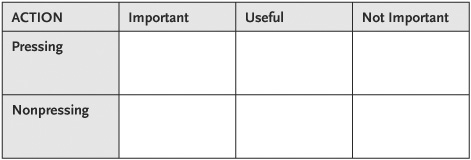

Table 5.1 gives sample decision-making procrastination distractions and sample do-it-now choices.

Although there is no sure formula that can guarantee the correctness of a decision before the results are in, inaction caused by indecisiveness is the wrong decision in the vast majority of situations. Act on the 49/51 principle: if you have a slight leaning in one direction, take that direction until the results suggest following a different path. How do you decide the percentages? There is no perfect solution, especially when a decision could go either way. Figure out the pros and cons of each direction, and the picture may begin to clear and give you weight to one direction over another.

What if you don’t recognize a decision-making procrastination problem, yet you suffer from the results of indecision? There is not much you can do. A big part of solving a decision-making procrastination problem is to recognize the problem. This can be tricky when different styles of procrastination coexist.

Decision-making procrastination can be cinched by other procrastination styles, such as blame avoidance procrastination, in which you defer a decision to avoid risking criticism. If you tend to follow a behavioral procrastination path, you decide on a direction, establish goals, and generate a strategic plan to meet your objective. Then it comes time for you to execute your plan. You are uncertain what to do when you meet your first barrier. In good behavioral procrastination fashion, you put off following through. When styles interconnect because of, say, uncertainty anxieties, you have the usual two problems to resolve: following through on the counter-procrastination action while addressing the co-occurring condition.

Information from this book can help clarify conditions in which procrastination is a problem condition, and the following problem-solving list covers how to meet this form of challenge:

1. A problem exists when you have a gap between where you are and where you’d like to be. The gap contains unknowns, and solving the problem is ordinarily going to require an evaluation, generating solutions, testing the solutions, and overpowering coexisting procrastination processes when they interfere with preparation for and execution of the solutions.

2. A lot depends on how you define a problem situation. A well-articulated question can help point you in a direction where you can find answers. Directions for solutions are often built into such questions. For example, what steps are involved in ending decision-making procrastination that applies to your situation? This question focuses on the problem and the importance of identifying steps for a solution.

3. Next, define the problem conditions. New questions can stimulate answers that expand and clarify problem-related issues. What, where, when, how, and why questions help to flesh out problem identification issues. What pressing decisions are you likely to duck? Where is this likely to occur? At what point (when) are you most likely to delay? What do you tell yourself when you hesitate? Why do you think you find it so troublesome to decide this issue? Play with different scenarios in which you reverse the questions to give direction to acting efficiently and effectively.

4. Reframing problems can lead to different options and conclusions. The idea is to reframe the situation so that you move from a procrastination to a do-it-now track. Use questions to reframe the process. What if my assumptions are inaccurate? What assumptions are likely to be accurate? What other assumptions can I consider? Imagine that your decision leads to unexpected consequences (which can be positive, negative, or both) without putting down or praising yourself. Obtain three alternative views from three people who ordinarily have different perspectives.

In solving a well-articulated problem, you may have many false runs in which you test solutions that don’t solve the problem. You may find solutions that are good enough but not perfect. However, once you engage the decision-making process, you are likely to find ways to actualize your capabilities by stretching them.

American diplomat and scientist Ben Franklin stated in his autobiography that by setting goals and striving to reach them, he found that he was not perfect, but he was still far better off than he would have been if he had not undertaken the challenges he set for himself.

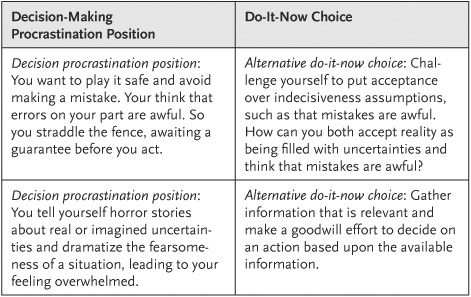

Problem solving may go into a holding pattern when decision-making procrastination gets in the way. Table 5.2 compares a decision breakdown process to a rational decision-making process.

The comparison in the table provides another way to view a Y decision: as a shift from a decision breakdown process to a rational process of making decisions based on concrete realities, where you weigh and balance choices, then act on the best option available at the time. When you face a Y decision between retreating and advancing, use this breakdown-rational contrast. It may be useful to ask who is calling the shots, the horse or the rider?

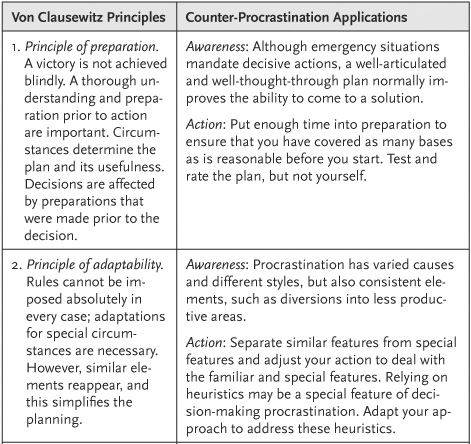

The nineteenth-century Prussian military strategist Carl von Clausewitz’s book On War has attracted interest from people in the business world who are interested in strategic planning. Its strategic planning content is of value to organizations that want to establish momentum, moving forward in changing circumstances where adaptation is critical. You can apply this same approach to improving the quality of your decisions, getting out of an indecision holding pattern, and enjoying the fruits of your productive labors.

Von Clausewitz’s approach centers on strategic planning and execution. He starts by defining strategy as the planning of a campaign that includes the coordination of tactics to achieve the main objective. These tactics are smaller-scale plans to manage each individual encounter. You can apply both strategy and tactics to go against procrastination and to end procrastination.

END PROCRASTINATION NOW! TIP:

DECIDE

Decisions are inescapable, so you might as well decide to decide.

Enter areas of uncertainty to gain clarity and direction.

Consider alternatives and consequences. Include the consequences of inaction.

Implement problem-solving actions.

Determine what works and what doesn’t and what could be useful with modifications.

Engage the next challenge and persist in actualizing your positive capabilities.

Table 5.3 describes seven principles that I abstracted from von Clausewitz’s book. His main message is to keep focused on what is important and to time and pace your actions efficiently. The principles and an application example are given in the table.

Here is a general principle for your battle to contest decision-making procrastination. You enter areas of uncertainty with a plan. Through executing your plan, you gain clarity and direction. You can apply this general principle (strategy) as you address both decision making and the other procrastination styles.

Forming the habit of acting decisively is rarely an overnight undertaking. It ordinarily takes a deliberate effort to familiarize yourself with a direct route to reasonable goals and action to get yourself out of a holding pattern. This familiarizing decision can get you out of an indecisiveness holding pattern.

When you are choosing between positive alternatives of roughly equal value, the experiences that follow are likely to be different. All things being equal, no one can tell if the way that was not chosen would have been better or worse or about the same.

What three ideas have you had for dealing with procrastination effectively? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.

What three top actions can you take to shift from procrastination toward productive actions? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.

What things did you do to execute your action plan? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.

What things did you learn from applying the ideas and action plan that you can use in other areas? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.