The most likely union of the two crosses, though opinions vary as to the intended width of the fimbriation, or white border, to the St George’ cross which some evidence suggests was much wider.

The opening chapters of W G Perrin’s 1922 study of British Flags first trace the origin of the flag as a national device. In the case of England, he goes on to examine the competing attibutions to several saints, among them St Cuthbert, St Edmund and Edward the Confessor, for the provision the central motif of what would much later become the Union flag. He concludes that by the time King Edward I rallied his armies to resist Welsh claims for independence in 1277 it was most likely the cross of St George under which they marched.

When, some seventy years later in 1346, his grandson King Edward III claimed the divine intercession of St George in his victory over the French at the Battle of Crécy, there was no question of ‘…the dethronement of Edward the Confessor from the position of “patron saint” of England and the definitive substitution of St George in his place.’1 The dedication to St George of a new collegiate chapel at Windsor dates from the same moment in our history.

For Scotland, the attribution of a national motif to a particular saint was more straightforward, with St Andrew the only contender. Perrin points out, however, that there is no direct evidence of the cross-saltire being adopted as a national ensign before the 14th century and then with some variety in the colour against which the white cross is displayed with black, red and yellow (the Stuart colours) competing with the more usual blue.2

The accession of King James VI of Scotland to the English throne raised the question of how the two established crosses could be equitably combined to project the authority of the new kingdom, particularly for ships at sea.

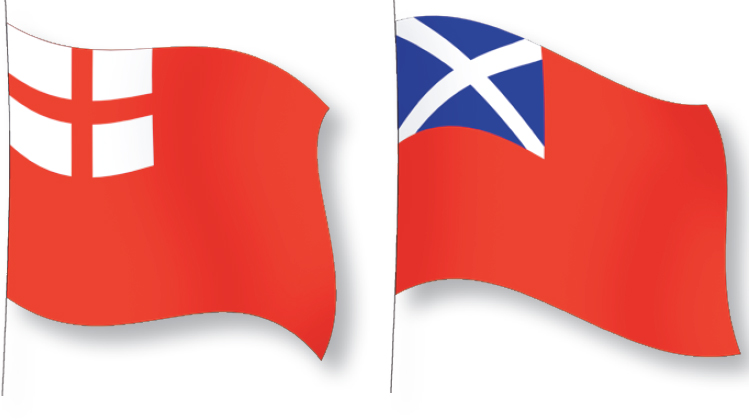

A royal proclamation of April 1606 calls upon ‘… our Subjects of South and North Britain, Travelling by Sea… shall bear in their maintop the Red Cross, commonly called St George’s Cross and the White Cross, commonly called St Andrew’s Cross joined together according to a form made by our heralds…’3 In addition, subjects of South Britain were to wear the Red Cross and those of North Britain the White Cross in their foretop. But whatever exact form the heraldic union took (for evidence of the original design was destroyed by fire in 1618), it did not please the shipmasters of Scotland who objected to the division of the saltire by the cross of St George and resisted its use until the formal Acts of Union between the two countries in 1707.

The most likely union of the two crosses, though opinions vary as to the intended width of the fimbriation, or white border, to the St George’ cross which some evidence suggests was much wider.

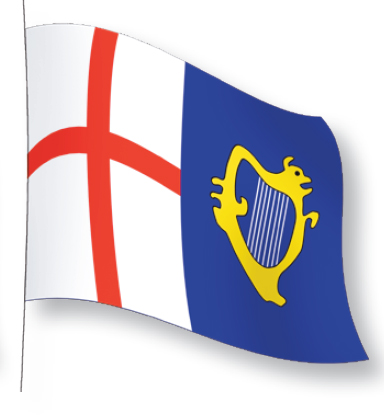

The quartered version of the Union Flag is sometimes referred to as the Commonwealth Flag. It is said to have been used by the fleet sent to return Prince Charles and the Duke of Buckingham from Spain in 1623 but a contemporary painting of the event shows no evidence of it.4

Royal Standard, early 16th century, flown by the Lord High Admiral of England.

Ensigns of the Elizabethan Navy. Both were flown during Lord Howard’s 1596 expedition to Cadiz.

Ensigns of the Jacobean Navy.

Despite Scottish reluctance to fly it, at the death of King James I in 1625, it is found in a list of flags and banners for display at the King’s funeral, referred to for the first time as the Union Flag.

Apart from the different flags flown at the foretop, there was nothing to distiguish merchant ships from those of the new king’s Navy Royal. A further proclamation of 1634 required English and Scotish merchantmen to desist from flying the Union Flag – possibly no hardship for the Scots, but perhaps an indication that the Navy had begun to feel undermined at home while threatened by the combined fleets of France and the Dutch Republic.

The Civil War and the execution of King Charles I in 1649 changed everything; the dynastic link with Scotland was broken and the Navy once again reverted to the flag of St George. When the passing of the Navigation Act of 1651 threatened Dutch hegemony over world trade, war threatened and the Commonwealth’s Generals-at-Sea determined on a new flag for the commander-in-chief to replace the Royal Standard. In place of the Scotish saltire the new standard brought together the cross of St George and the harp of Cromwell’s newly-conquered Ireland. There are variants of this flag but evidence of at least two paintings from the First Dutch War shows it used as both a bowsprit jack (see below left) and as a masthead standard.5

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam [CC0 1.0]

Detail of painting by Jan Beerstraaten showing General-at-Sea George Monck’s Resolution flying the St George cross with the Irish harp from the bowsprit jackstaff at the Battle of Scheveningen on 10th August 1653 during the First Dutch War. A larger section of the painting is shown in the background to the previous page.

With Scotland politically re-united with England in 1654, the Union Flag was reinstated but still denied to merchantmen. Yet another proclamation of 1674 forbade the use of ‘any Jack made in imitation’6 in attempts to gain the same privileges in foreign ports as those enjoyed by ships of the newly named Royal Navy. But by the Acts of Union of 1707 the Red Ensign with the Union Flag in the upper canton was formally adopted by both the Royal Navy and Mercantile Marine.

Union with Ireland came into effect on 1st January 1801, from which date the red saltire of St Patrick was joined with that of St Andrew. Similar debates as in 1606 over the relative widths of the two saltires and their borders were eventually settled, giving us our national flag and, from 1864, the three separate ensigns in use to this day.

17th century mercantile ensigns of England and Scotland.

1653 standard combining the cross of St George with the Irish harp.

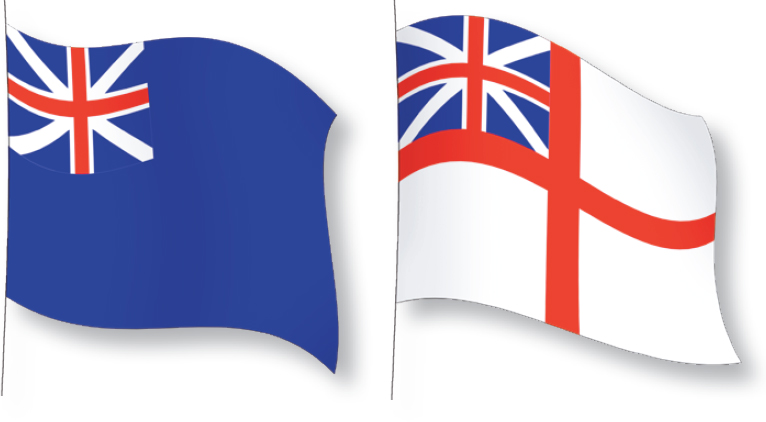

Ensigns of the Blue and White Squadrons. In 1702, the St George’s cross was added to the white ensign to avoid confusion with the plain white French ensign.

Devotees of Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey novels will be familiar with Flag Officers of the Red, the White and the Blue; but which has precedence, from which masts were which flags to be flown and when did the order of the colours change?

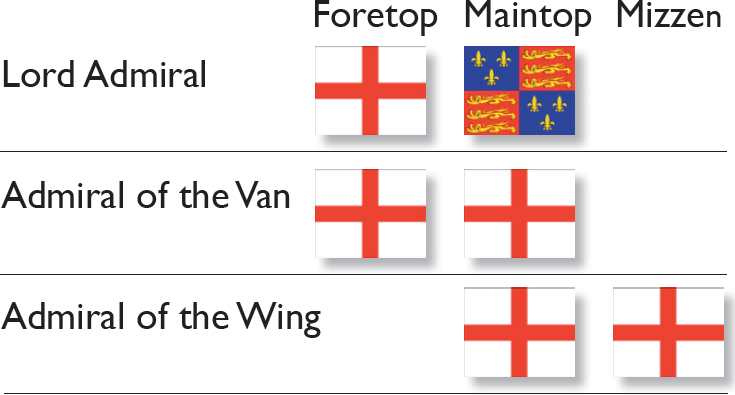

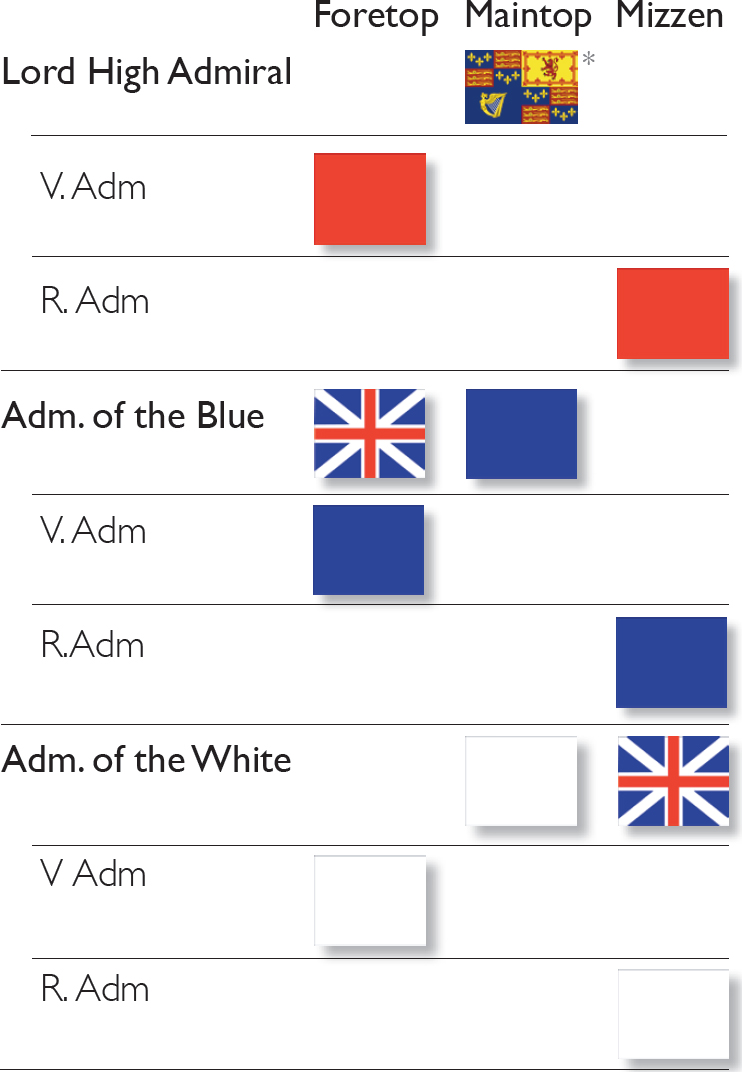

As fleets grew in size and tactics moved from mêlée battles at close quarters to fleet engagements in line-of-battle, new forms of organisation were needed with fleets divided into smaller, more manageable squadrons. One of the earliest records of a squadron formation is that proposed by King Henry VIII’s Lord Admiral John Dudley in 1545, in which he specifies a distinct hierarchy of flags ascribing an order of precedence to the masts from which they were to be flown.7 The distinctions between the squadrons can be tabulated as follows:

The private ships of each squadron flew a single St George’s flag from main, fore and mizzen tops respectively. By the time Sir Edward Cecil gathered his fleet for the disastrous expedition to Cadiz in 1625, there was a clear instruction on the division of the fleet into three squadrons, each under three admirals with, for the first time, the colours red, blue and white assigned to the squadrons in descending order of seniority. Sources differ on the positions of flags but an expedition two years later under the Duke of Buckingham intended to capture the Isle de Ré gives a clearer indication of how the squadrons might have been identified:

* senior Admirals would fly the Union flag

Private ships within the squadrons wore a pennant matching their Flag Officers and at the same masthead, though at this date there is no record of corresponding ensigns being worn. With a change of colour precedence to red, white and blue in March 1653, this squadronal structure remained in place, with the adoption of corresponding ensigns, until colour squadrons were abandoned in 1864.

Promotion path for Flag Officers to 1805.

The ensigns shown above are those in effect from 1702 to 1801. After the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 an additional rank of Admiral of the Red was created, the highest rank attainable until 1862 when more than one Admiral of the Fleet was permitted. Two years later the squadronal system was abandoned as having no further useful tactical purpose.

Ensign of the East India Company, early 19th century.

Red Ensign reserved for British merchant ships from 1864. Note the change to 2:1 ratio.

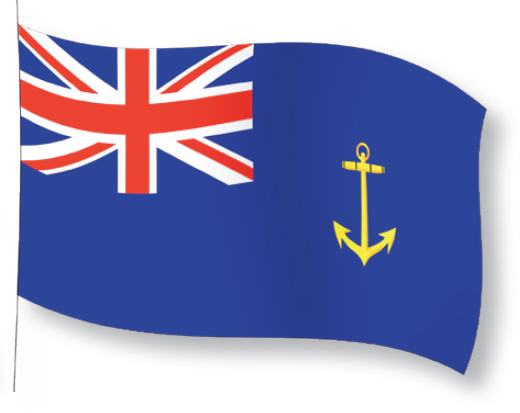

Blue Ensign of the Royal Naval Reserve and Fleet Auxiliaries denoted by the gold anchor.

White Ensign flown only by HM ships and, from 1859, by members of the Royal Yacht Squadron.