Timeline: Shapes, shutters and semaphore

If the development of flag signalling was carried out at sea, the process was very different for semaphore, which was not adapted for use at sea until the second decade of the nineteenth century and only then experimentally.

Semaphore has its roots in several experiments in ‘distant writing’ – the literal translation of the Greek words tele (distant or far) and grapho (writing) and many of the devices were known as ‘telegraphs’, often misnamed as ‘semaphores’ and vice versa. Both are effectively distance signals animated either by shutters or articulated arms. It is the latter, still in use today with hand flags replacing steel or louvered wooden arms, which is generally termed semaphore – literally translated from Greek as carrier (phero, to bear) of signs (sema). To understand how we got here, the timeline on these pages traces the colourful history of the devices and their various champions among whom were eminent scientists, a French Abbé, an 18th-century rake, two English clergymen, a rear admiral and a lieutenant colonel of the Royal Engineers*.

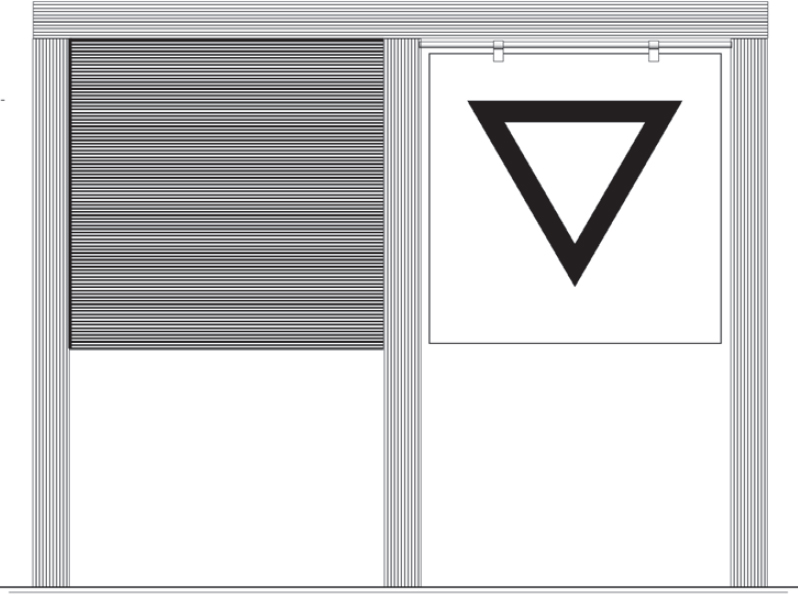

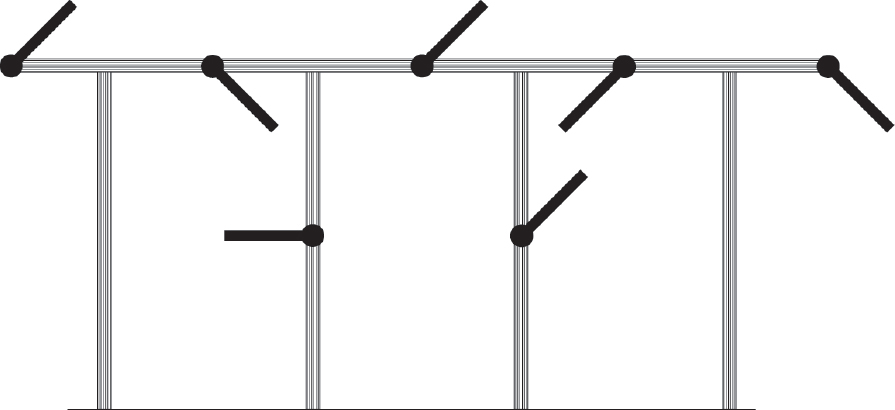

Sir Robert Hooke’s telegraph presented in 1684. Successive shapes were to be pulled out from the housing to spell out words in his own coded alphabet. The example below spells out ‘HOOKE’.

| 1684 |

Notwithstanding the listing of ‘A Mute and Perfect Discourse by Colours’ which describes ‘How, at a window, as far as eye can discover black from white, a man may hold discourse with his correspondent’ in the Marquis of Worcester’s 1673 Century of Inventions,1 it was the eminent scientist and polymath Sir Robert Hooke who can claim to be the first to have proposed an organised means of telegraphing information over long distances. In a paper delivered to the Royal Society in 1684, Hooke describes a system of shapes representing letters of the alphabet hung within a wooden frame that could be repeated from station to station a fixed distance apart, such that ‘none but the two extreme correspondents shall be able to discover the information conveyed’.2 |

| 1690 |

Guillaume Amontons, a French physicist and instrument maker, who had earlier presented a system similar to Hooke’s symbolic telegraph, demonstrates a new telegraphic device to the Dauphin in the Jardin du Luxembourg. A contemporary illustration shows a single moveable arm on a short flagpole but few other details; it pre-dates by just over 100 years the first true semaphore. |

Image: Bonhams

Sir Francis Blake Delaval 1727-1771, after Joshua Reynolds. Edgworth’s telegraph from Newmarket ended on the roof of Delaval’s townhouse, No 11 Downing Street.

| 1767 |

Richard Lovell Edgeworth, an Anglo-Irish inventor, politician and a member of the Birmingham Lunar Society, sets up a relay of signal apparatus with stations 16 miles apart between London and Newmarket. Funded by his eccentric friend Sir Francis Blake Delaval who was anxious for news of the horse racing,3 this private line was probably the first successful telegraph and may have used a forerunner of the device that he would later advocate to the Royal Irish Academy in 1795. |

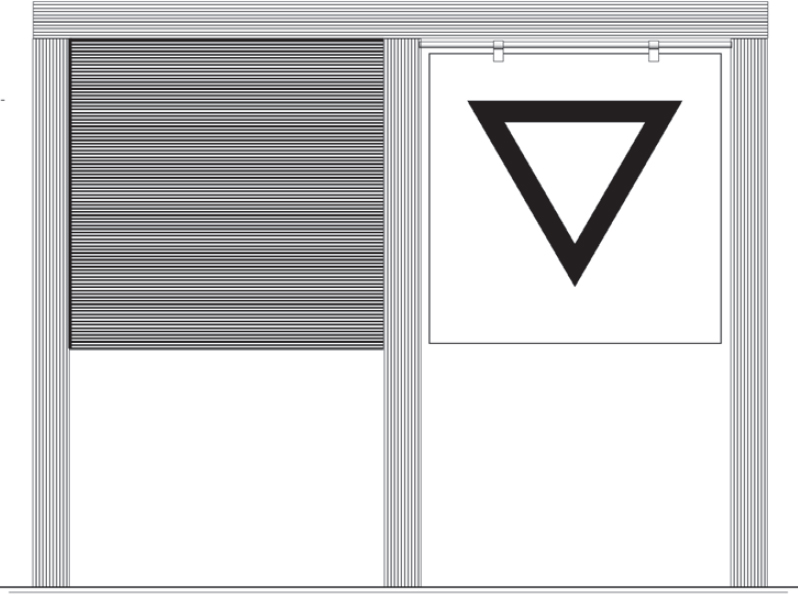

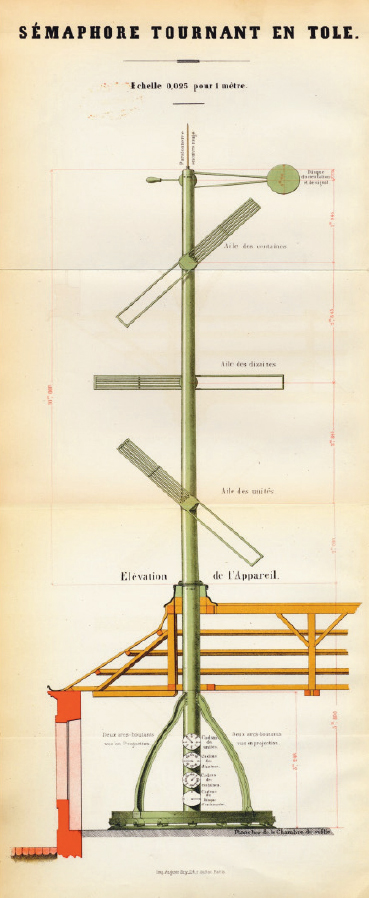

Virtual model of Abbé Chappe’s semaphore of 1794. The column was 33ft (10m) and the central beam, or ‘regulator’, louvered to reduce windage, 15ft (4.62m). At each end were 6ft 6in (2m) counterbalanced ‘indicators’, all connected by pulleys to control handles at the base, often housed within a purpose-built or existing tower. (Source: contemporary engravings and Burns, p.40, see note 3)

| 1792 |

Abbé Claude Chappe, one of whose four brothers, Ignace, was a member of the Legislative Assembly, successfully demonstrates his ‘T’ telegraph in Paris. Its articulated arms are capable of 196 different positions but only 92 most easily distinguished combinations are used. In the previous year, against a background of revolutionary unrest, he had demonstrated a shutter system and a ‘synchronous’ telegraph in which the hands of a dial indicated symbols similar to those used by Hooke, only to have the equipment for both of these systems seized and burnt by the mob fearing they were being used to communicate with the imprisoned King Louis XVI.4 |

| 1793 |

Despite a similar setback with the firing of his first experimental semaphore, Chappe secured the support of the Assembly, now re-named the National Convention, for a full trial. This took place two days before the fifth anniversary of the storming of the Bastille and led Joseph Lakanal, one of the three Convention members appointed to oversee the trials, to wax lyrical in his somewhat chauvinistic praise of Chappe’s invention on 26th July 1793: |

| |

‘What brilliant destiny do science and the arts not reserve for a republic which, by the genius of its inhabitants, is called to become the nation to instruct Europe.’5 |

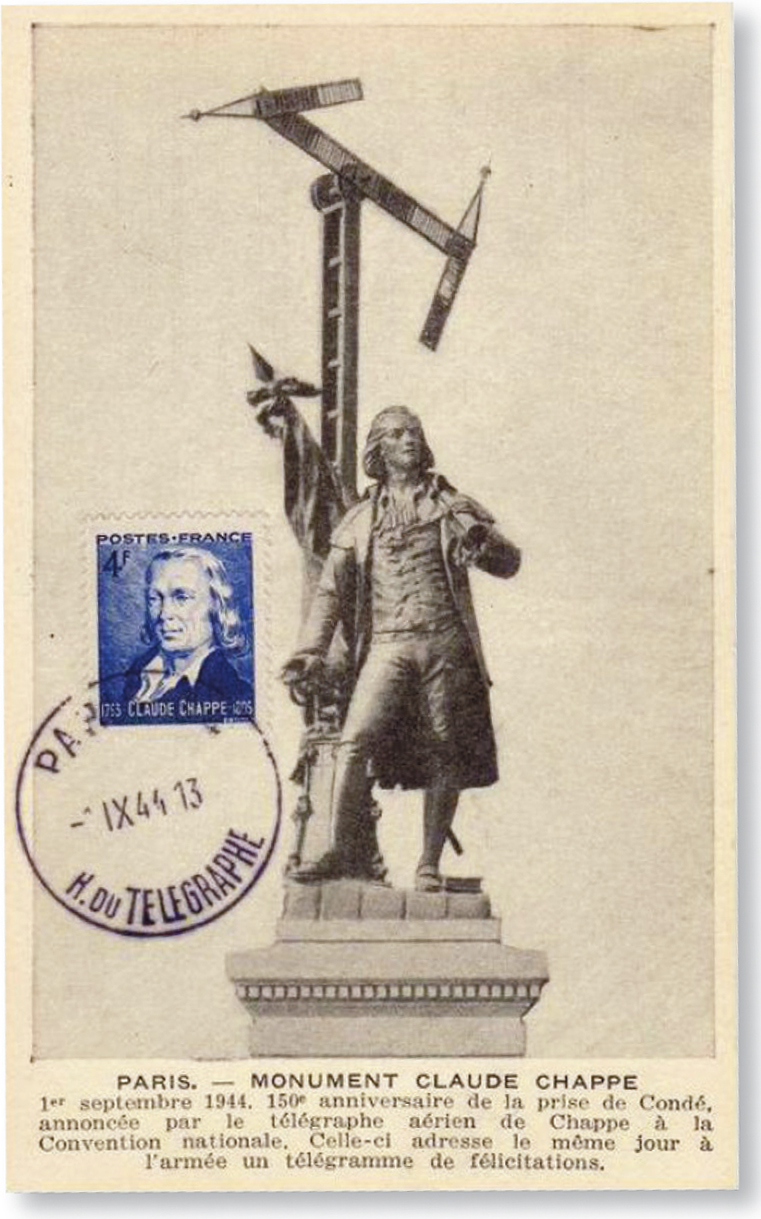

Source: www.wikitimbres.fr

Postcard view of Chappe’s monument in Paris and commemorative stamp issued in September 1944 to mark the 150th anniversary of the first transmission.

| 1794 |

Chappe’s system was approved by the Convention and by August 1794 a line between Montmartre and Lille was established. On 15th August the first transmission brought the news in under two minutes that the border town of Le Quesnoy had been re-taken from the Austrians with whom, and her allies Britain and Holland, France had been at war since April 1793. Driven by the imperative and proven benefit of good communications in wartime, it was the first of a rapidly expanding network of semaphore chains that by 1815 covered 1,780km (1,112 miles) with 224 stations. By the time the electric telegraph arrived in 1844, the semaphore network extended to 534 stations connecting 29 major towns and cities in France, with extensions into Belgium, Holland and Milan. Tragically, Chappe did not live to see the full effect of his invention – dogged by ill health and undermined by rival claims to the design of his system, he took his own life in January 1805. |

| 1795 |

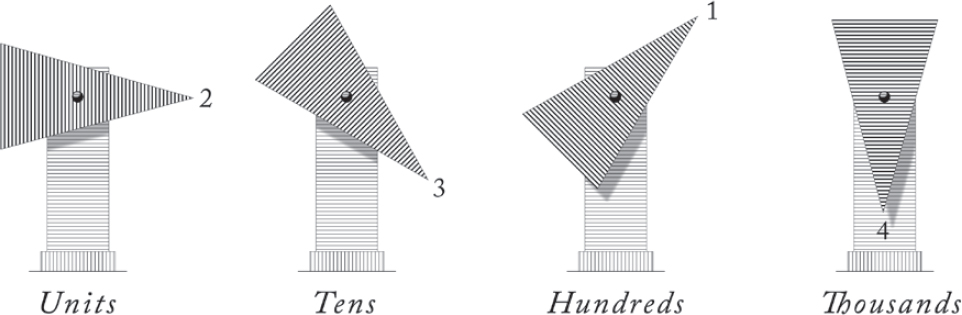

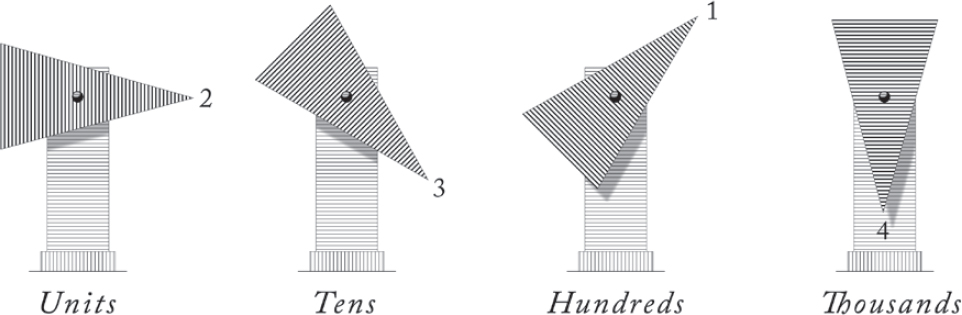

Almost exactly a year after the successful launch of Chappe’s semaphore in Paris and nearly thirty years since his Newmarket experiments, Richard Edgeworth assisted by his son (probably his third son Lovell, the seventh of his twenty-two children by four wives) demonstrated a new version of his telegraph, the first in the British Isles to employ rotating arms. Using an indexed code based on multiples of seven possible positions of the triangular pointers – the eighth, pointing upwards, was the rest position – they successfully transmitted four messages across the North Channel between Donaghadee and Portpatrick, a distance of twenty miles. But, despite early encouragement from the Admiralty, the isosceles triangles were judged to be too indistinct and the decoding process too cumbersome to make it viable and, to Edgeworth’s disgust and deep frustration, his scheme was turned down. A pamphlet of 1797 defending his ‘Tellograph’, aimed at the Earl of Charlemont, President of the Royal Irish Academy, did not exactly help his cause.6 |

Edgeworth’s telegraph re-drawn from engraving in Rees’s Cyclopedia, 1819 (see note 6). Rotating clockwise from viewers position in 45° increments, the arms indicated numbers 0 to 7.

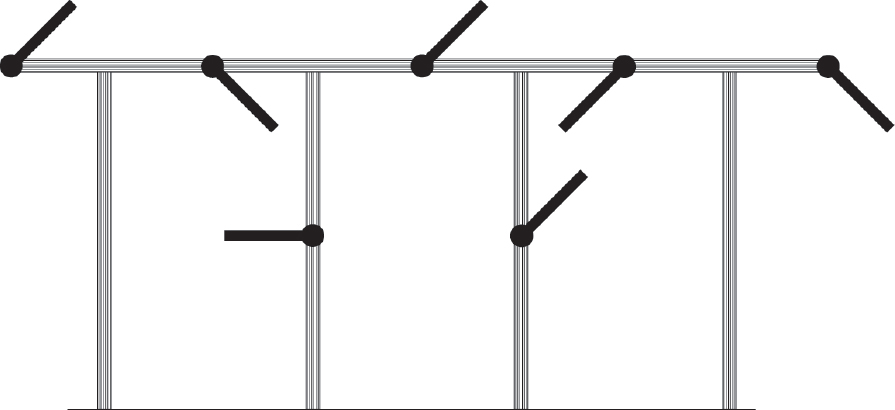

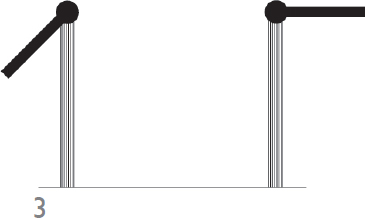

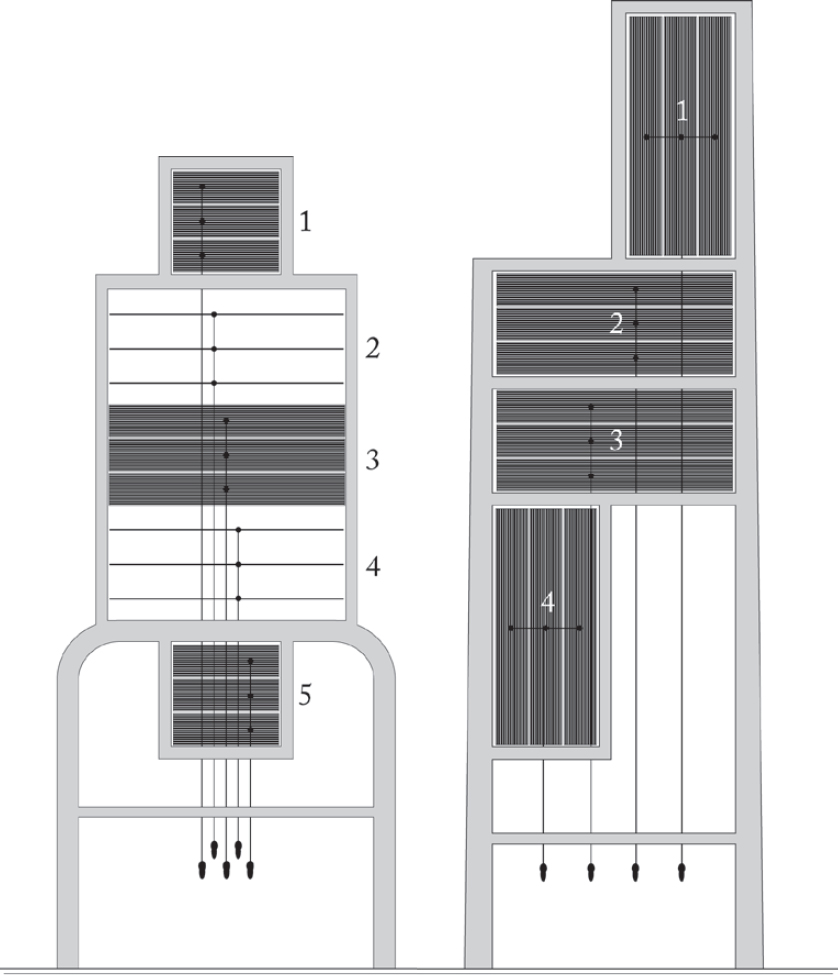

Gamble’s five and four-shutter telegraphs based on engraved plates from his 1797 Essay of Different Modes of Communication by Signals. The horizontal shutters were 7ft x16ft (2.13m x 4.88m); it was the four-shutter system erected between spare topmasts of two 74s that Gamble demonstrated to Admiral Parker.

Virtual model of Murray’s six-shutter telegraph offering 63 different permutations. Each octagonal shutter was 5ft (1.5m) square and the whole structure stood 28ft 6in (8.7m) tall. (Source: Broadsheet published by S.W. Fores of Picadilly, 25th March 1826)

| 1795 |

At the same time that Richard Edgeworth was demonstrating his ‘Tellograph’ to the Irish Academy in August 1795, the first of two new telegraph systems, almost identical in principle, was being demonstrated to Admiral Sir Peter Parker, C-in-C Portsmouth on Portsdown Hill. |

|

News of Chappe’s success had reached England soon after the first successful transmissions, though sources differ on the route by which it came. Probably the most authentic is the account given by the Reverend John Gamble, Chaplain to the Duke of York, commander of the British Army in Flanders. In his Essay on the Different Modes of Communication by Signals published in 1797 and fulsomely dedicated to the Duke, he tells of a French prisoner in whose pocket a drawing and description of Chappe’s semaphore was found and, following a detail description of the apparatus, he relates how he suggested to the Duke that ‘…a machine might be constructed to answer the purpose better.’7 |

|

Gamble was careful to acknowledge the work of both Chappe and Edgeworth, and one or two more eccentric proposals, before outlining how he had brought his own proposals for a shutter based telegraph to the Admiralty from whom he received an order on 19th July for a trial between Portsdown, Spithead and the Isle of Wight, some fourteen miles away. Despite the apparent success of the trial witnessed by Admiral Parker on 6th August, he learned three weeks later ‘in a desultory conversation with one of their Lordships’8 that a rival shutter system proposed by the Reverend Lord George Murray, second son of the 3rd Duke of Athol, was preferred. Was it hubris at French advantage with Chappe’s semaphore that the shutter system was adopted in England? Was Murray, whose system the Admiralty assured Gamble they had seen ‘above a twelvemonth before’, better connected? Or was his six-shutter telegraph, which Gamble likened to ‘.. adding a fifth wheel to a carriage which, on many accounts, would be inconvenient’,9 just that much better than Gamble’s four shutters? |

|

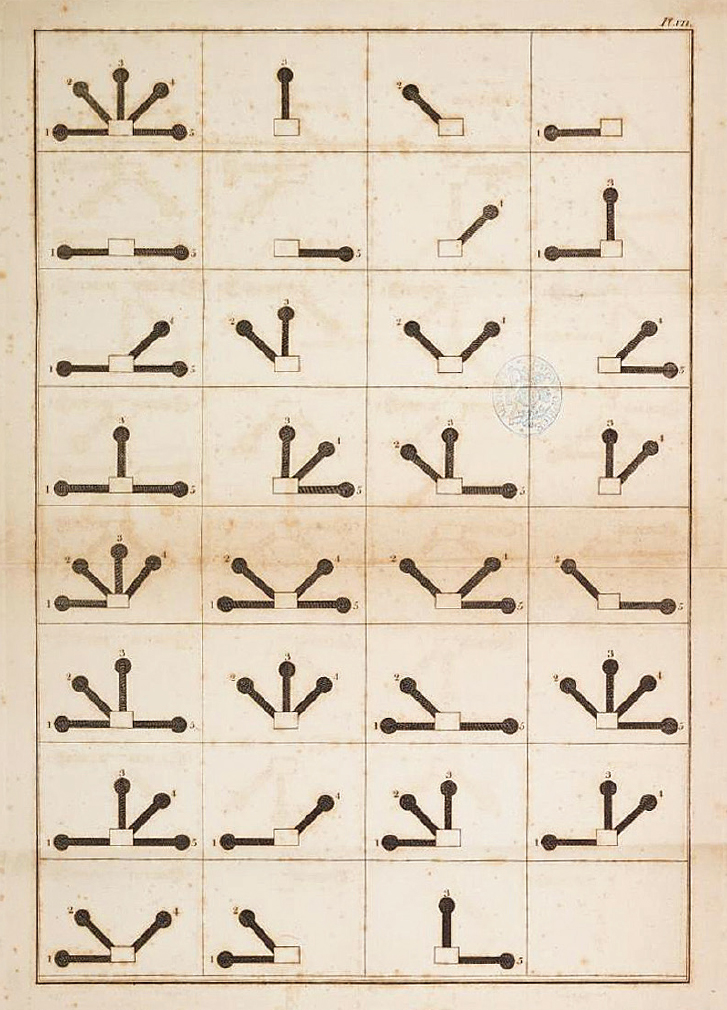

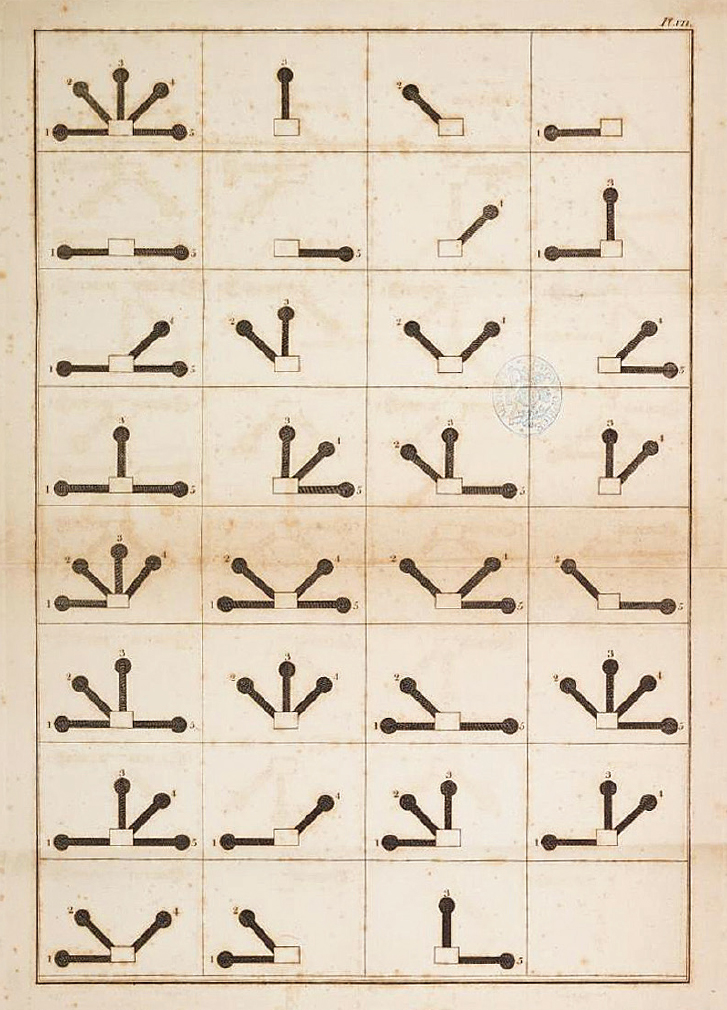

Despite his disappointment at the Admiralty’s preference for the Murray shutter system, the Rev. Gamble soon switched his attention to a new proposal for a five-arm ‘Radiated Telegraph’. It was the first moving-arm telegraph proposed in Britain. |

Google Books

Code sheet for Gamble’s ‘Radiated Telegraph’ from his 1797 essay ‘Different Modes of Communication by Signals’. Each diagram had space for an updated code, allowing an infinite variation, provide everyone had the current version.

| 1796 |

Having made their decision, the Admiralty wasted no time in commissioning Murray, later elevated to a new post created by King George III in March 1796 as Director of Telegraphs to the Admiralty, to build a chain of fifteen telegraphs connecting London and Deal. On 27th January, the first signal was sent and acknowledged in two minutes. By September, twenty-four more stations linked the Admiralty in London with the Dockyard in Portsmouth. Signals to and from the Western Squadron in Plymouth were passed along the chain of coast signal stations (see page 39) to Portsmouth and thence by telegraph to London. |

|

In the same year, Richard Edgeworth came back again with a single-pole telegraph but there is no evidence it was ever used. More spectacular was the seven-arm gantry structure, anticipating by some fifty years the first railway signals. It was demonstrated at the Tuillerie Gardens in Paris but again there is no evidence that its 823,543 possible permutations found favour over Chappe’s system. |

Seven-arm semaphore demonstrated at the Tuillerie Gardens in Paris, 1796. With each arm able to show six positions, or be hidden behind the structure, the number of possible combinations was 77.

Dictionaire Etymologique,1861

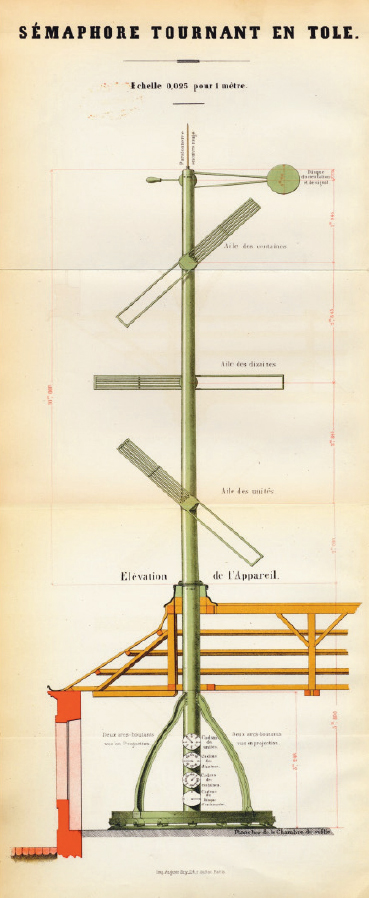

Diagram of Depillon semaphore from the Dictionaire of 1861 shows a 50ft (15.3m) steel column with an additional disque d’orientation that increased the number of signal permutations from 301 to 2,401. The whole structure rotates on roller bearings at the base.

| 1800 |

M. Charles Depillon, a former artillery officer, submits proposal for a three and four-arm coastal telegraph. It is the first device to be described as a sémaphore but the network he envisaged for the French Atlantic coast was not approved until a year after his death in 1805. Nevertheless the ‘Depillon’ semaphore outlasted the Chappe system by nearly a century, the last one closing in 1937.10 |

| 1806 |

The Murray telegraph is extended to Plymouth with the addition of a further twenty-two stations, opening on 4th July and allowing transmission and acknowledgement of a time signal from the Admiralty in three minutes. |

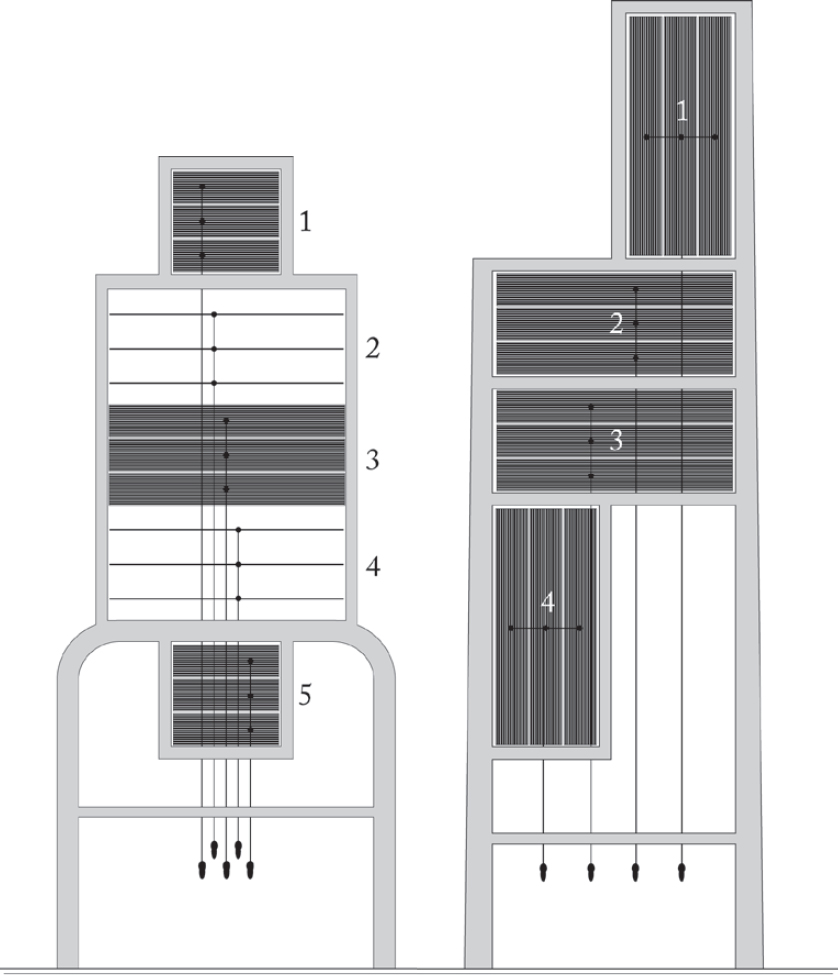

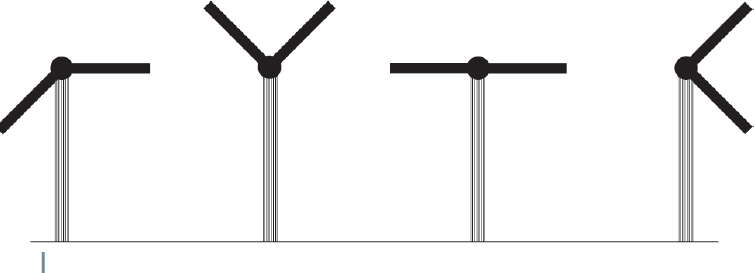

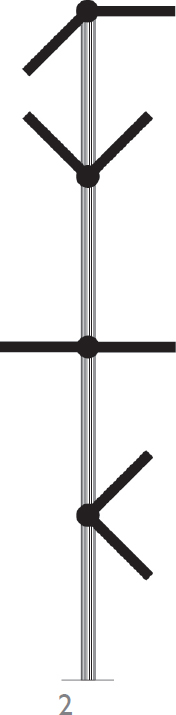

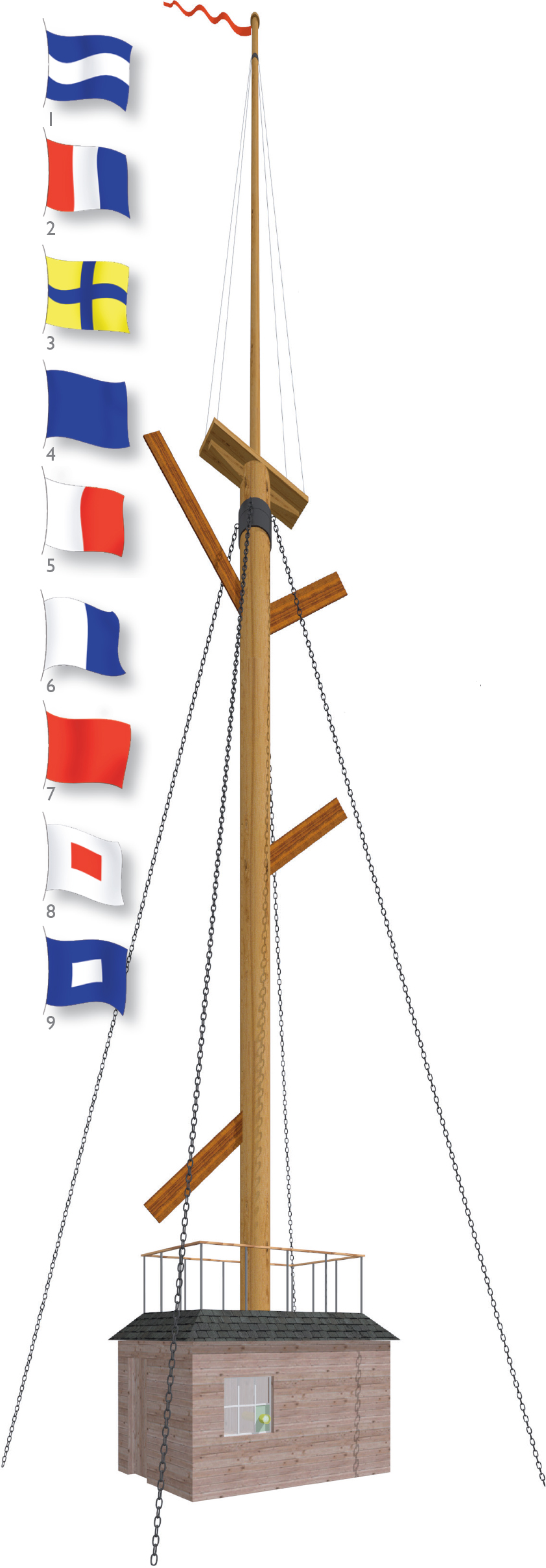

Pasley and Popham semaphores to same scale: (1) Pasley’s 1st Polygrammatic Telegraph, 1807; (2) Pasley’s 2nd Polygrammatic Telegraph, 1810; (3) Popham’s two-post sea-going semaphore, 1816; (4) Pasley’s Universal Telegraph, 1822.

| 1807 |

Sir Charles Pasley, a captain in the Royal Engineers, proposes his first ‘Polygrammatic’ (meaning capable of signalling more than one letter or number at a time) Telegraph. |

| 1808 |

Colonel John McDonald publishes his Treatise on Telegraphic Communication (see page 14), later arguing that any system ‘…that cannot express any three figures from 1 to 999 simultaneously is absurd’.11 Stressing the advantage of a coded system, he advocates a thirteen-shutter telegraph, dismissing Depillon’s French semaphore as ‘a wretched contrivance’. |

| 1810 |

Pasley introduces his 2nd Polygrammatic Telegraph, having had the opportunity of studying the French single-pole system as firsthand during the Walcheren Expedition of the previous year on which he published an account in Tilloch’s Philosophical Magazine. |

Survey of London, LCC, 1935

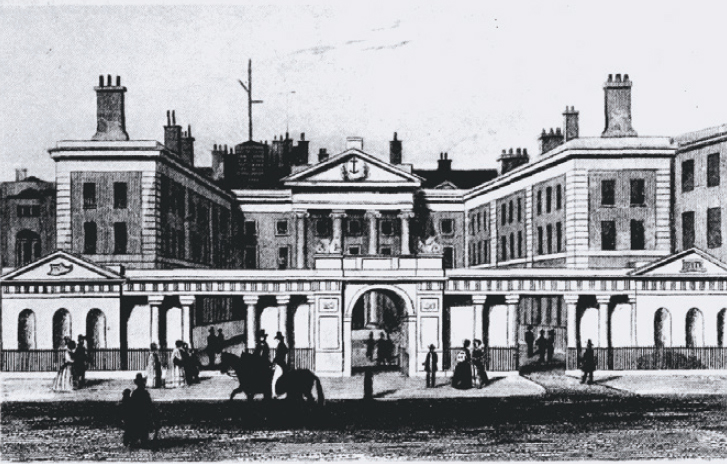

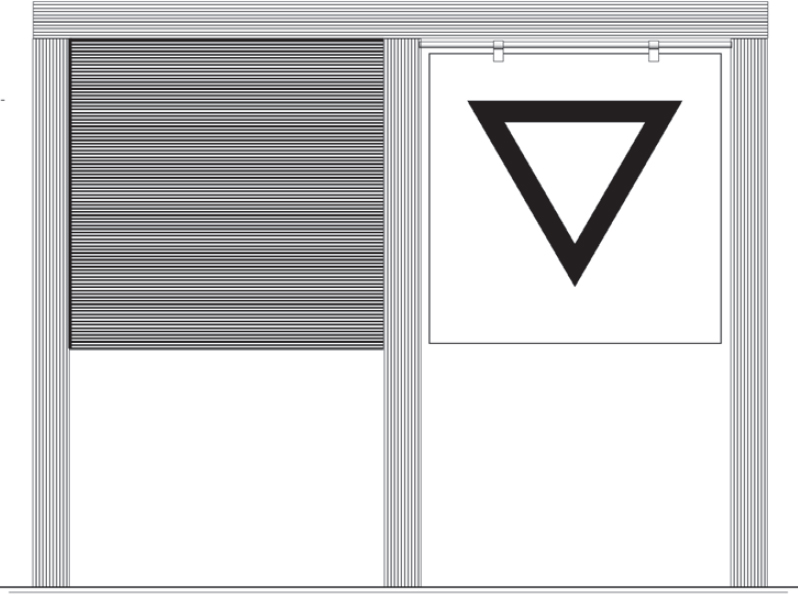

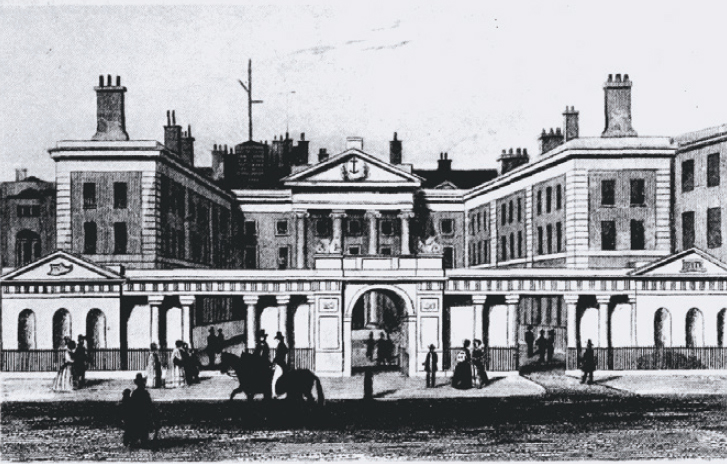

Popham’s single-pole semaphore replaced Murray’s shutters on the roof of the Admiralty in Charing Cross (present-day Whitehall) in 1816.

| 1814 |

With Napoleon held captive on the island of Elba, Murray’s shutter telegraph, always intended as a temporary measure, and the network of coastal stations are closed down, only to be promptly re-instated the following year with the Emperor’s escape from Elba. Within eleven days of the Battle of Waterloo, plans are drawn up for a permanent installation. |

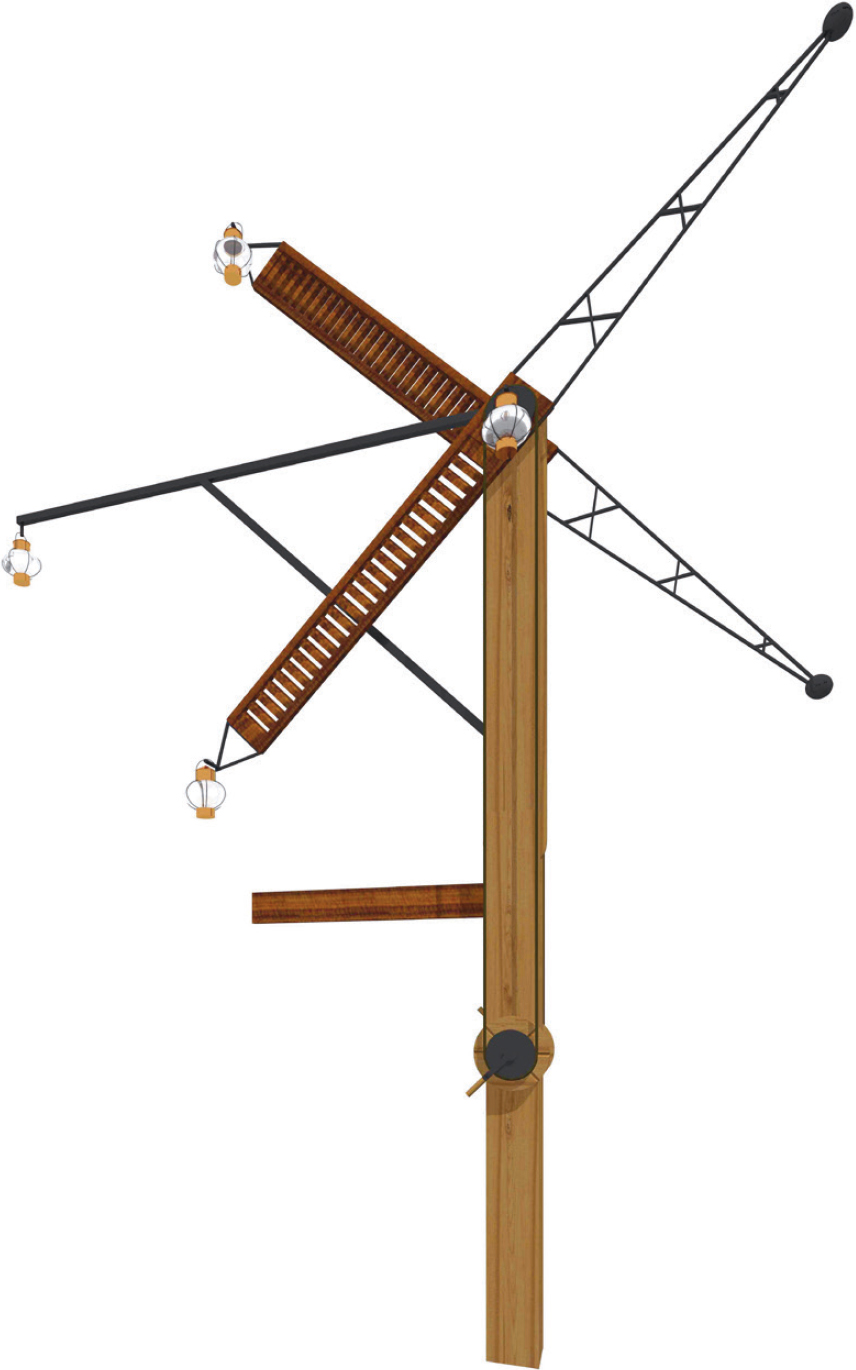

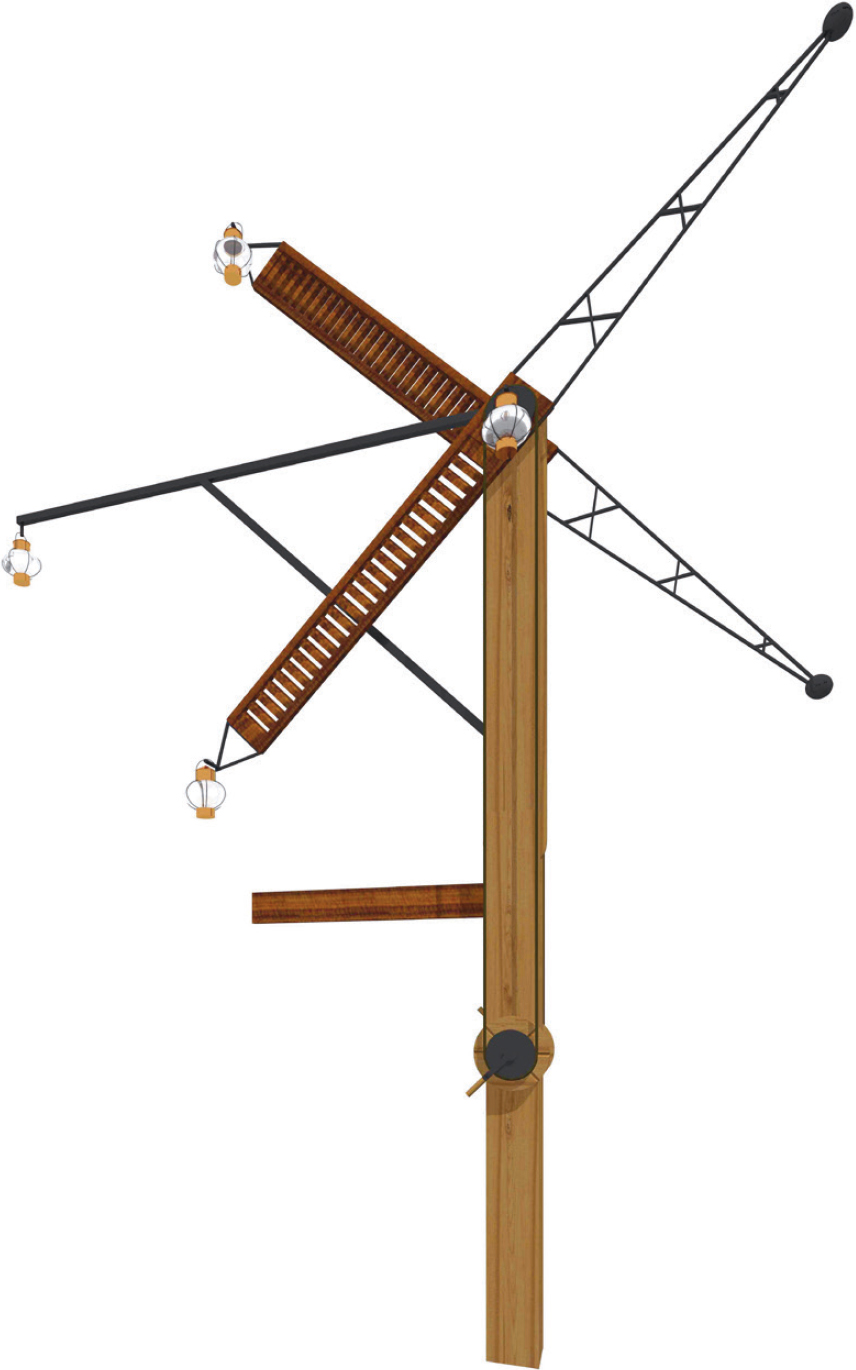

Virtual model of Pasley’s Universal Telegraph showing lights rigged for night signalling. The light cantilevered off to the viewer’s left acts as the night-time directional indicator, shown also in its daytime position. (Source: C Pasley, Description of Universal Telegraph, (London, T. Egerton, 1823)

| 1816 |

Rear Admiral Sir Home Popham’s single-pole, two-arm semaphore, probably based on the Depillon masts, early versions of which had been captured from the French, is adopted by the Admiralty with a reduced-height two-pole version supplied for use at sea. |

| 1817 |

John Macdonald publishes details of what he calls the ‘British Semaphoric Telegraph’ comprising three double arms on a single 60ft (18.3m) mast with the angles controlled by lines to the end of each arm rather than by pulley round a central pivot. In the same year he proposes his ‘Minor Semaphoric Telegraph’ that has no less than six arms on a single pivot capable of 2,592 ‘distinct and simple combinations’. In describing this and |

|

Macdonald’s other inventions, H P Mead could not resist the conclusion that ‘…it was as well for the sanity of all concerned that the scheme never matured’.12 |

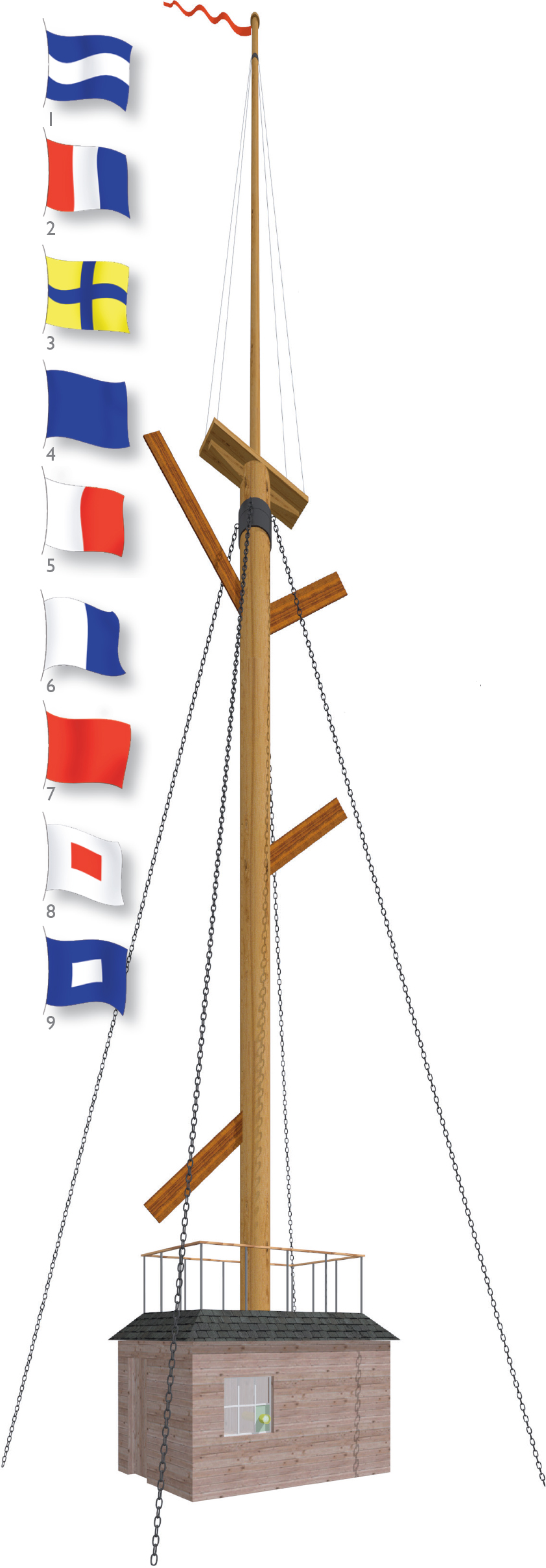

Virtual model of Watson’s 1827 Marine Telegraph displaying numerals 716 which was allocated to the British barque Prince Regent in Watson’s General Telegraphic List of 1840. Note the telescope trained attentively on the next station in the chain. (Source: Mechanics Magazine Vol 8, 1828, p.24)

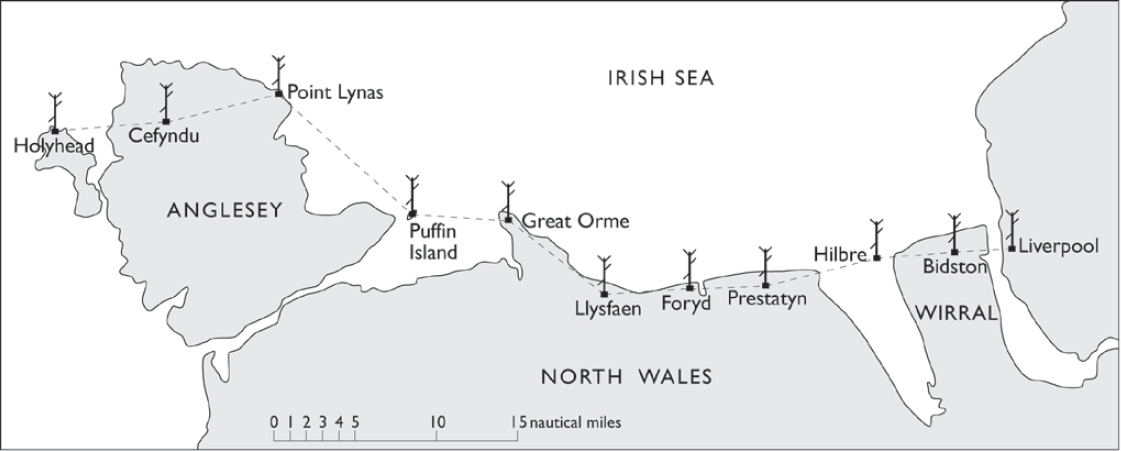

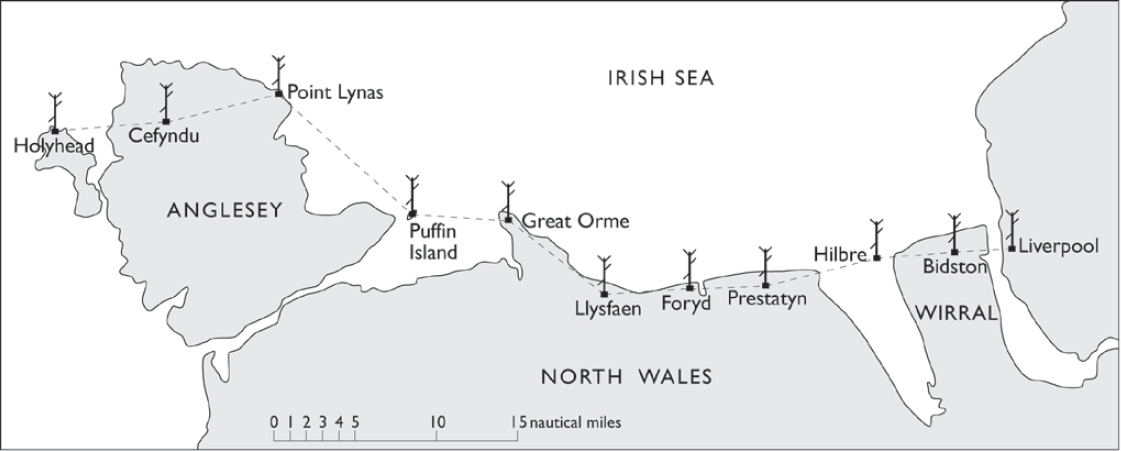

the 11 stations of Watson’s Holyhead to Liverpool Telegraph.

| 1820 |

The semaphore line to Chatham is made permanent using Popham’s semaphore. |

| 1822 |

Semaphore established between London and Portsmouth with new locations and structures replacing the Murray shutter telegraph. |

|

In the same year Charles Pasley, now a lieutenant colonel, publishes details of his ‘Universal Telegraph’. It is the forerunner of the eventual seagoing masthead-mounted semaphores with trials carried out on ships at the Nore and on the mast of an East Indiaman, the Vansittart. |

| 1826 |

Construction begins on the new Admiralty semaphore to Plymouth but is discontinued after five years with news of developments of the electric telegraph. |

| 1827 |

The first commercial telegraph is inaugurated between Holyhead and Liverpool using a three-arm single-pole semaphore and telegraphic code developed by a former lieutenant of the Oxford Militia, Bernard Watson. To allow communication with ships at sea, Watson provided, for a fee, his own set of numerical flags (see right) with which merchant ships could pass information to their owners through any of the semaphore stations. |

|

The Admiralty, possibly as the result of some partisan lobbying, opts for Pasley’s semaphore in place of the Popham system on HM ships. |

| 1842 |

First railway semaphore introduced on the London to Croydon Railway, approved by the new Inspector General of Railways, none other than Major General Sir Charles Pasley. |

* As with the work of W G Perrin on signal flags, any fresh look at the history of semaphore must acknowledge the scholarship in the 1930s of Commander Hilary Mead RN. See endnotes.