CHAPTER SIX

THE MYTHOLOGY OF ISOLATION

WHAT ABOUT TASMANIA? What about Easter Island and Australia? What about the indigenous populations that have been genetically isolated for tens of thousands of years? This is a legitimate set of objections, already noted in the commentary on the 2004 Nature paper by another scientist.1 All these objections are concerned with the isolation of populations for thousands of years. If any population of humans was isolated for several thousand years, they might not descend from Adam.

In scientific modeling, it is common to make an initial prediction with a simplified system. We then progressively add complexity to refine our estimates with increasingly realistic models. This progression from simplified to complex modeling is our approach in this analysis. First, Chang’s 1999 paper used a very simplified model, with no barriers to interbreeding across a single intermixing population. In this model, universal ancestry arises in just seven hundred years. Next, the 2004 Nature study modeled universal ancestry across the globe, with several barriers to intermixing. This model shows universal ancestry arises in just a couple thousand years. Finally, my study in 2018 extended these results to apply to everyone alive at AD 1. We estimate that, most likely, a couple in the Middle East six thousand years ago would likely be ancestors of everyone by AD 1. There, however, was a single important assumption in this model that we will examine here.

These final estimates rely on the same assumptions as the 2004 Nature study: no populations were unable to mix with others. Now, we want to consider the validity of this assumption. First, I want to clarify how this assumption figures in the simulation. Mixing between populations everywhere across the globe was possible, at least in principle. No populations were prohibited from intermixing with neighboring populations. No populations were forced to be totally isolated. The simulations, however, did not force intermixing between different populations, used a very low rate of migration, and did not include modern transportation to boost migration. There is important subtlety here. The simulation did not assume that all populations mixed. Instead, the simulation merely assumed it was possible for all populations to mix. Still, we need to assess whether or not it is possible that all populations in the world could mix with one another.

WHAT IF THE ASSUMPTION IS WRONG?

What if this assumption is incorrect? What if one or more populations were isolated for thousands of years in our past? No universal ancestors could arise except before or after that time of isolation. If the isolation was for a very long period of time, this could substantially push back when universal ancestors would arise. What would it mean if a specific human population was, in fact, isolated? The most likely candidates might be the indigenous populations of Tasmania. If this population were isolated from six thousand years ago till AD 1, would this be a problem?

First, if Adam and Eve lived before the population was isolated, it will not matter. For example, if Tasmania were totally isolated from nine thousand years ago onward, this would rule out a universal ancestor at six thousand years ago, but not one more ancient than this. If Adam lived ten or twelve thousand years ago, there would no reason to doubt that Tasmanians all descended from him by AD 1. We have not insisted on placing Adam and Eve at a specific time. Our precise estimate would change, but a recent Adam and Eve would still be likely.

Second, a small number of people that are, in fact, isolated may not be a problem, because theology does not speak with scientific precision. If a few isolated populations do not descend from Adam at AD 1, they would be rare and undetectable exceptions to the rule. As we will see, the doctrine of monogenesis teaches we all descend from Adam and Eve to the “ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8). It is possible for the doctrine of monogenesis to be valid from a theological point of view, even if there are very rare and undetectable exceptions.

Third, our specific understanding of people outside the garden could head off any theological problems that arise from exceptions to the rule of monogenesis. Take the indigenous Tasmanians as an example. For argument’s sake, just for a moment, let us presume they did not descend from Adam. As we will see, we would not be able to determine this for sure from any scientific evidence. We would not be able to pronounce them as outside Adam and Eve’s lineage, even if they did not, in fact, descend from them. Even if we could make this determination, this would not necessarily legitimize the abuses that Tasmanians suffered when they were colonized and exterminated. As long as we have a coherent way of acknowledging their human worth and dignity, it may not be a problem that they are outside Adam and Eve’s lineage. In the final part of this book, I work out just such an understanding to the people outside the Garden, affirming their worth and dignity.

Therefore, even if a rare population is genealogically isolated, we do not face an ultimate problem. At stake here is merely the difference between total universal ancestry and nearly universal ancestry, with a few rare populations undetectably left outside Adam and Eve’s lineage. We should be open to see what the evidence tells us about rare, isolated populations. Ultimately, the genealogical hypothesis does not depend tightly on what we find. As we will see, moreover, the evidence cannot tell us definitively anyway.

The goal of this chapter is to review the evidence for and against the genealogical isolation of individual populations. I want to determine the strongest evidence against total universal ancestors in the recent past. The goal here is to test the assumption of the simulation with evidence. We will find there is no definitive evidence of genealogical isolation, but we cannot be sure. The strongest case comes, perhaps, for the isolation of Tasmania, but even the evidence here is not definitive. Definitive evidence might be outside our view. We may not ever have the evidence to tell us for sure.

THREE TYPES OF ISOLATION

Three types of isolation are important here: genetic, geographic, and genealogical isolation.

Genetic isolation is observable in genetic data. Studying the information in genomes from present-day and ancient individuals, we can determine when segments of DNA are shared between different populations. We can estimate the extent to which populations mixed, and when this mixing took place. As some of the examples will demonstrate, the details are complex, and mixing events can easily be missed.

Geographical isolation is determined using several lines of evidence. Of course, the presence of barriers to migration are important, such as large bodies of water. Across a divide, such as between Tasmania and Australia, we can also study whether animal populations are different, and whether cultural developments are shared or developing in different ways. Together, these lines of evidence can demonstrate geographical isolation.

The critical question is whether or not genealogical isolation persisted for several thousand years. This question is only answerable if genetic or geographic isolation can reliably identify genealogical isolation. As we will see, genealogical isolation does not correspond with either genetic or geographic isolation. Instead, the question of genealogical isolation poses a dilemma of complementary universal negatives. A single genealogically isolated population will prevent a universal ancestor from arising. However, a single migrant or mixing event will break genealogical isolation. On one hand, it is nearly impossible to rule out the isolation of every population. On the other hand, however, it seems impossible rule out low levels of migration in order to demonstrate a population was genealogically isolated for long periods of time. Science, therefore, cannot definitively determine whether genealogically isolated populations have existed in our past or not. Genealogical isolation is not directly observable. We can rule it out with evidence, but we cannot definitively demonstrate it with evidence.

In some important senses, therefore, it is not possible to demonstrate with evidence whether or not genealogical isolation prevented universal genealogical ancestry. Remember, undetectably low levels of migration are all that is required for universal genealogical ancestors to reliably arise in the recent past. I expect, for this reason, for there to be some unresolvable disagreement between scientists. The key questions here cannot be fully adjudicated by evidence.

GENETIC MIXING EVERYWHERE

Genetic evidence can falsify the hypothesis of genetic isolation, and usually does.2 In this way, genetics is producing an increasingly strong case against genealogical isolation. This supports the hypothesis of recent universal ancestors. As data increases, more evidence of mixing is expected. Most genetics studies only consider small portions of the genome.3 Whole genome sequencing usually reveals mixing in the past, even in populations once thought to be genetically isolated. Similarly, ancient genomes provide additional evidence for ancient migrations.4 Even though human populations are fragmented and might be genetically isolated at times, the data demonstrates a pattern of pervasive intermixing everywhere.

In 2013, a study was published by Peter Ralph and Graham Coop.5 Using genetic data from over one thousand Europeans, they found genetic evidence that all Europeans share about two to twelve genetic common ancestors one thousand years ago. This is consistent with millions of shared genealogical ancestors that all Europeans share, just one thousand years back in history. They write, “Individuals from opposite ends of Europe are still expected to share millions of common genealogical ancestors over the last 1,000 years.” They find millions of universal genealogical ancestors, on the one hand, with just a handful of universal genetic ancestors, on the other hand. The vast majority of the universal genealogical ancestors did not leave DNA to everyone.

In 2014, another study used genetic data to infer populations mixing events across the globe, “revealing admixture to be an almost universal force shaping human populations.”6 It was able to detect over one hundred events in the last four thousand years. Many of these mixing events correspond to known historical events, like the Arab slave trade and the Mongol empire. Other mixing uncovered events before history was recorded. The study revealed a churn of mixing between nearly all populations all across the globe, but a few populations did not show evidence of genetic mixing. Does genetic isolation of a few rare populations demonstrate these populations were genealogically isolated? No.

GENETIC ISOLATION IS NOT GENEALOGICAL

Genetic isolation does not demonstrate genealogical isolation. There are several reasons mixing events would be missed, and Coop’s 2014 study details several of them.7 Populations can be genealogically linked even if genetic analysis cannot demonstrate intermixing in the past. Of particular importance, moreover, is that statements of genetic isolation are often made in reference to portions of the genome. One part of the genome might show genetic isolation, while another might demonstrate genetic mixing. In these cases, this conflicting result demonstrates that the population is genealogically linked to others, and not isolated.

It is sometimes claimed, nonetheless, that certain populations have been genetically isolated for long periods of time. Most precisely, these claims should be understood as genetic isolation of specific portions of genome, but not necessarily of a population’s whole genome. For example, portions of DNA from the Khoisan people of southern Africa8 and the Aborigines of Australia9 appear to be genetically isolated for tens of thousands of years. This evidence is consistent with substantial cultural and geographic barriers that made mixing and migration less common. This evidence, however, is often based on only portions of the genome, and only demonstrates genetic isolation of these portions. Looking at whole genomes, taking into account all the genetic information, there is usually genetic evidence of mixing.10 This means that the Khoisan people, we know from evidence, were not genealogically isolated, even though parts of their genome have been genetically isolated for a large period of time.

The Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean are an important case study of the pattern of progress in our knowledge. They entered the news when John Allen Chau, a twenty-six-year-old man from the United States, was killed. He attempted to contact these isolated islanders in order to tell them about Jesus. News stories often repeated the claim that the islanders had been isolated for over fifty thousand years. The islanders were famously hostile to outsiders, it seems. Some of this hostility is likely caused by the very recent history of British colonization of the islands. Did this hostility, however, stretch back for thousands of years? Could they really have been totally isolated for fifty thousand years?

The Andaman islanders are among the most isolated populations on earth. Their isolation, however, has not been total. For a long time, anthropologists wondered about the origins of the islanders. They share external characteristics like skin color and hair type with Africans, even though they are in Asia. This, in addition to the geographic isolation of the islands, suggested an interesting hypothesis. Perhaps they arose from the initial expansions of African Homo sapiens over fifty thousand years ago, and then they remained isolated on the island. Two genetic studies, from 2005 and 2006, supported this hypothesis, showing divergence and isolation for tens of thousands of years.11 These two studies, however, only looked at small portions of the genome. Subsequent studies in 2013 used more genetic data from their neighbors, and variation across the whole genome. These analyses showed intermixing between the islanders and their neighbors, and a much more recent settlement of the island.12 The perception of the ancient and total isolation of the Andaman Islands was an artifact of incomplete genetic and historical data.

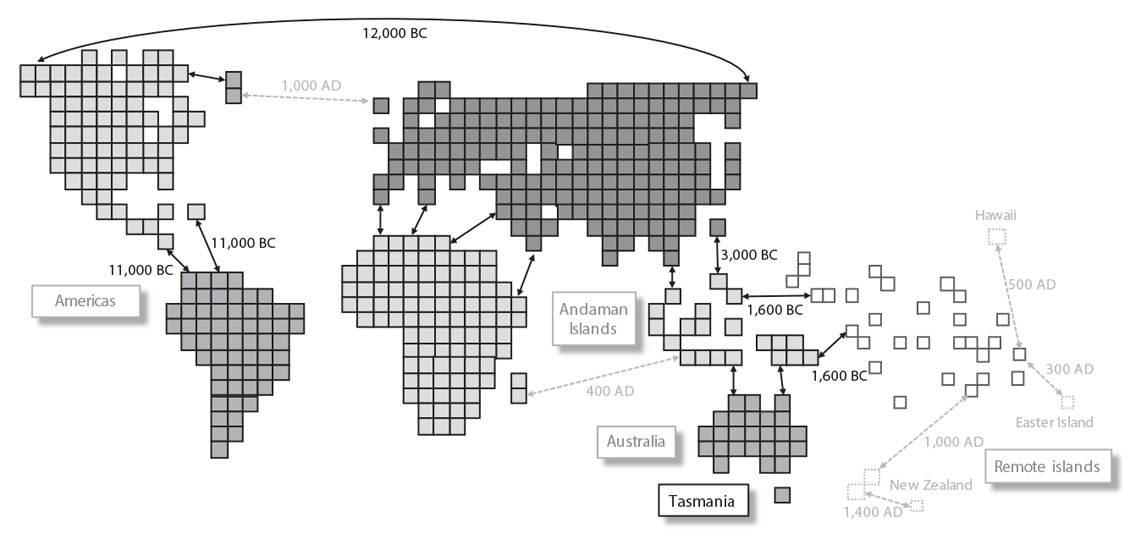

Figure 6.1. Several examples of isolation are considered. The strongest case is for the isolation of Tasmania, but even this is not definitive.

Looking at any small portion of the genome, populations can seem isolated. Looking at whole genomes, however, we usually see intermixing with other populations. Likewise, more genetic information from neighboring populations often reveals evidence of mixing. The more we look, the more evidence of mixing we find.

GEOGRAPHIC ISOLATION IS NOT GENEALOGICAL

The geographic isolation of some populations merit special discussion (fig. 6.1). For example, the Americas, Australia, Tasmania, Hawaii, and Easter Island seem to be, at first glance, isolated for very long periods of time in the past.

At first, the geographic isolation of the Americas seems insurmountable. It was thought that migration to the Americas was contingent on an intermittently open land bridge in Beringia or seafaring technology to cross the Pacific Ocean. Evidence, however, suggests continuous immigration in boats along a costal route and another route through the Aleutian Islands.13 Even if immigration ebbed at times, genealogical isolation would require zero successful migrants to the Americas for centuries and millennia. Even if we find genetically isolated populations in the Americas, it does not follow that the Americas were genealogically isolated too.

Likewise, Australia is often offered as definitive evidence against recent common ancestors. Rising seas submerged land bridges across the world, making it more difficult to cross from Southeast Asia to Australia and separating Tasmania from Australia. For this reason, we might expect Australia to be genealogically isolated.14

The initial colonization of Australia adds important information. Land bridges never extended all the way to Australia. The last stretch required crossing a fifty- to one-hundred-kilometer-wide body of water. Until the arrival of Homo sapiens about forty to sixty thousand years ago, this final gap was not crossed. It is thought that boats or rafts might have been a unique capability of Homo sapiens, at least in this region, and were used to cross the strait in order to colonize Australia.15 Similar seafaring feats enabled Homo sapiens to migrate to unexpected places for at least one hundred thousand years.16 This is evidence that ancient Homo sapiens were capable of crossing large bodies of water. In this case, the genetic data settles the debate. A 2013 genetic study uncovered evidence that about four thousand years ago there was “substantial gene flow between the Indian populations and Australia, well before European contact, contrary to the prevailing view that there was no contact between Australia and the rest of the world.”17 The authors note, “This is also approximately when changes in tool technology, food processing, and the dingo appear in the Australian archaeological record, suggesting that these may be related to the migration from India.”

It is possible that the iconic dingoes of Australia arrived on Indian ships, just thousands of years ago. With evidence of large-scale mixing, we expect there were numerous migrations too small to detect both before and after this major event four thousand years ago.18 The geographic isolation of Australia, therefore, is not evidence of genealogical isolation.

Tasmania is a large island in the present day, and it presents the strongest case for genealogical isolation. It was settled tens of thousands of years ago, while it was connected to Australia by a large land bridge that was submerged by rising seas by about fourteen thousand years ago, and difficult to cross by about ten thousand.19 As evidence of this difficulty, dingoes came to Australia four thousand years ago, but to Tasmania much later. There, nonetheless, remain several habitable islands between Tasmania and Australia. Using these islands as a broken bridge, the crossing might still be possible, though difficult, perhaps with the same sort of boats that enabled colonization of Australia in the first place. The real question is if the barriers prevented all mixing. Even if mixing was limited to rare events, universal ancestors arise. For this reason, we cannot know for sure if and when small amounts of migration took place to Tasmania. The oral tradition of Aborigines, to this day, retains ten-millennia-old memories of when the seas rose.20 They would have known that Tasmania existed across the strait, for example, four thousand years ago. It seems reasonable to wonder if at least one boat managed the crossing every century or so. In this case, I grant that skepticism is reasonable, and informed scientists might disagree. We cannot say for sure, nonetheless, one way or another. Future work, however, could settle the question. The remains of dingoes in Tasmania, if dated to 3,000 years ago, for example, would demonstrate there was exchange across the strait. Whole-genome studies of ancient DNA from Tasmanians, also, could demonstrate migration from Australia, perhaps against expectation. Right now, however, evidence does not tell us for sure.

The most remote islands—like Hawaii, Easter Island, and the most eastern end of Polynesia—are very difficult and dangerous to find without modern technology. For this reason, these islands are key bottlenecks that push back estimates of the most recent ancestor of all present-day humans.21 However, these islands were colonized within the last couple thousand years or so.22 They are not, therefore, relevant to universal ancestors more ancient than about six thousand years ago.

In any case, absence of positive evidence for migration does not demonstrate isolation. Alongside the limitations of genetic studies, rising seas limit the archaeological evidence of migration in the distant past. From about sixteen to seven thousand years ago, seas rose about 120 meters, submerging very large coastal areas across the globe.23 As the seas rose, they erased much of the archaeological evidence for migration and early settlements.24 Colonization in paleo-historic times might have been in boats, along coasts and rivers, enabling rapid dispersal over long distances.25 This dual problem of costal dispersion and submerged evidence limits our understanding of the most geographically isolated areas. Moreover, for universal ancestors ten thousand years or more ancient, most of the land bridges would be still passable for thousands of years. During this time, Australia, Tasmania, and the Americas would all be easier to access. If ancestry of nearly everyone is sufficient, a far more recent date is plausible.

THE ANCIENT DNA REVOLUTION

The study of ancient DNA promises to revolutionize our knowledge of human history. In 2018, the book Who We Are and How We Got Here was authored by David Reich, one of the leading scientists in this area.26 The review of his book in Nature puts it well:

What his and other labs are uncovering is the tremendous degree to which populations globally are blended, repeatedly, over generations. Gone is the family tree spreading from Africa over the world, with each branch and twig representing a new population that never touches others. What has been revealed is something much more complex and exciting: populations that split and re-form, change under selective pressures, move, exchange ideas, overthrow one another.27

We sit at the beginning of this revolution. Thousands of ancient genomes have been sequenced already, but not yet analyzed or published. In another decade, we will know far more about who we are and where we came from. We will see in increasing detail how we are connected to one another. If the pattern continues, the evidence for populations and mixing in the past will grow.

Ancient DNA is presenting us with mysteries and puzzles, even as it shows we are more connected than we imagined. In 2018, several ancient genomes from across America were analyzed and published. In this study, one individual from about ten thousand years ago in South America showed evidence of mixing with populations in Australia.28 None of the genomes to the north showed any evidence of this mixing event, and scientists are not sure how this happened. This presents a puzzle to solve in the coming years. We are just beginning to understand the complexity of human history.

Were any populations totally genealogically isolated for thousands of years? These are honest questions and objections, but our understanding of the past is being reworked. A major realignment in our understanding of human history is being guided by a tidal wave of genetic data. What seemed like reasonable conclusions of isolation in prior decades are much less plausible now. As we learn more about the past, long-term isolation seems less and less likely. Were there any human populations isolated for tens of thousands of years? Perhaps with the exception of Tasmania, certain conclusions of long-term and total isolation increasingly seem like mythology. Even in the case of Tasmania we do not know for sure one way or another.

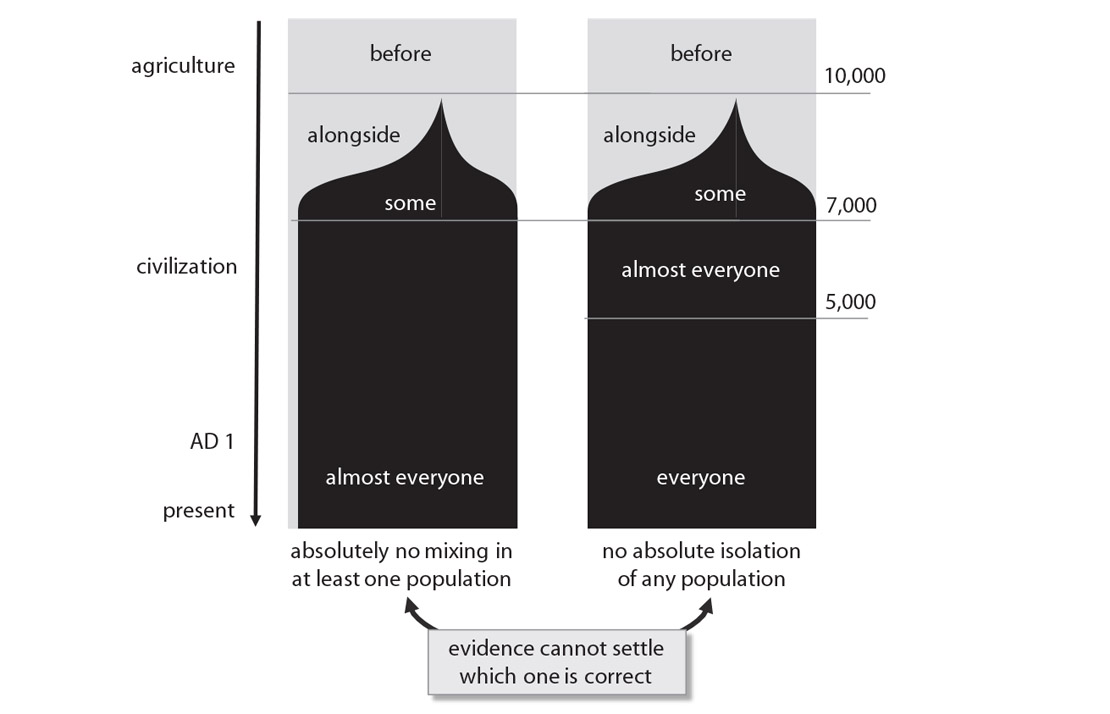

Figure 6.2. Digging into the details, universal ancestry poses a dilemma of two universal absolutes. Either (left) there were populations with absolutely no mixing for thousands of years, or (right) there were absolutely no populations that were totally genealogically isolated. Genealogy is outside the genetic streetlight, so we may never know definitively from evidence alone. Depending on the theology adopted, this may not matter.

CAUGHT BETWEEN TWO NEGATIVES

We do not have a way of definitively demonstrating genealogical isolation. Looking across all the genetic data, what if we found a population that really was genetically isolated for tens of thousands of years? Even this would not be evidence that they were genealogically isolated. Initially, there was hope that genetics might determine if and when populations were genealogically isolated.29 However, genetic data cannot detect low levels of migration in the distant past.30 Genetic isolation, therefore, does not demonstrate genealogic isolation.

The most likely consequence of rare interbreeding is genetically isolated populations that are not genealogically isolated. Remember, genealogic isolation is broken with a single successful dispersal event. Consequently, to demonstrate genealogical isolation, one has to prove that absolutely zero successful immigration has taken place over thousands of years. Most genealogical ancestors, however, do not leave any genetic evidence in their descendants.31 Most of the DNA that is passed on is not identifiable DNA, and is, therefore, unobservable in genetic data. This is not a low-probability loophole. Genetic information is unable to rule out genealogical relationships in the distant past. It is, therefore, not able to demonstrate genealogical isolation.

For any multimillennium period in our distant past, were any populations genealogically isolated? Evidence is mounting for interbreeding everywhere. Will we ever know for sure that there were never genealogically isolated populations? Answering either yes or no requires making one of two absolute negative claims, each of which is difficult to substantiate. We just do not have the evidence required to definitively determine which answer is correct.

On one hand, answering, “Yes, there were genealogically isolated populations” requires asserting there was zero successful migration or intermixing for thousands of years. This negative is not possible to demonstrate with evidence from either genetic or archaeological data. Those skeptical of the yes answer can posit at least a tiny amount of migration and intermixing, which would undetectably break genealogical isolation.

On the other hand, answering, “No, there were no genealogically isolated populations” requires asserting that there were zero populations that were isolated for thousands of years. This negative requires comprehensive knowledge of all populations in our distant past. Those skeptical of the no can posit that somewhere, somehow an isolated population existed.

We are faced, therefore, with a dilemma between two claims that are difficult, if not impossible, to substantiate. Absolute negatives, of either sort, are nearly impossible to demonstrate with evidence. What are we to do in situations like this? At the very least, reaching the limits of the evidence, there is flexibility in the scientific account.

It is possible that we all descend from Adam and Eve. What then is the likelihood that Adam and Eve, six thousand years ago, in the Middle East, would become ancestors of everyone by AD 1? What about at ten thousand years ago? Or twelve thousand years ago? We do not have the evidence to know for sure. Without definitive evidence, some scientists might conclude that, for example, it is most likely that Tasmania was totally isolated between six and two thousand years ago. Even then, evidence does not demonstrate this definitively. It remains possible that a single boat each generation could have crossed the strait to break genealogical isolation. It is possible that further research, especially into ancient DNA, might falsify the hypothesis of isolation. At this time, however, we cannot evidentially demonstrate genealogical isolation with high certainty, nor can we demonstrate it false.

THE GENEALOGICAL HYPOTHESIS

What should we conclude at this impasse? There is a puzzle here, without definitive evidence to settle our questions. Making an “inference to the best explanation,”32 perhaps invoking Occam’s razor, we might conclude that mixing does not exist where there is no evidence of mixing. This seems reasonable, but ancient DNA is sparing with Occam’s razor.33 Over and over again, we are finding out that ancient history is more complex than the simplest explanations of limited data.

Where evidence is sparse, as it is here, a better mode of reasoning might be hypothesis testing. Under this mode of reasoning, we can be sure that no evidence has definitively demonstrated genealogical isolation. Perhaps some populations are geographically and genetically isolated, according to current knowledge. This, however, is not strong evidence against a rare interbreeding event.

More careful modeling or additional evidence might resolve some questions, at least in part. It might take a philosopher to untangle the epistemological knot. In the meantime, perhaps we describe universal ancestry of everyone at AD 1 as “likely under a disputed assumption,” if Adam and Eve lived six thousand years ago. The more ancient we move Adam and Eve back in history, the more certain we become they are universal ancestors. For example, if Adam and Eve lived ten thousand years ago, we might describe universal ancestry as “likely under a plausible assumption.” If they lived fifteen thousand years ago, perhaps it is just “very likely.”

Either way, this scientific debate may be entirely ancillary to the theological questions at hand. Moving Adam and Eve slightly back in time overcomes most scientific objections. Theology does not make claims with scientific precision anyway, so nearly universal ancestry by AD 1 may be sufficient for the doctrine of monogenesis. Looming objections about human dignity and worth can be addressed in our theology of those outside the Garden. Whatever the outcome of remaining scientific debate, we can be certain that if Adam and Eve existed, then the vast majority of the earth’s population were their descendants long before AD 1. The scientific debate might continue on about a few exceptions to this rule, but this debate may be unresolvable with evidence. This technical debate, moreover, should not concern us as we move forward into theological reflection.