THE RENAISSANCE TRIANGLE: BRITONS, MUSLIMS, AND AMERICAN INDIANS

The Renaissance energy for exploration, along with the need for places to market goods propelled Britons to look eastward at the Turks and the Moors. It also directed them westward to America. In the half century between the establishment of the Turkey Company and the beginning of the Great Migration to North America, there were travelers and traders, pirates and adventurers, and migrants and emigrants within the triangle of England, the Muslim Mediterranean, and America.

Actually, during the Age of Discovery there were various triangles in the English experience. From the 1560s on there was the England-Newfoundland-Africa triangle in which Britons fished in Newfoundland, then sailed to the Christian and Muslim Mediterranean to sell their harvest, then returned home.1 There was also the infamous slave triangle between Bristol, sub-Saharan Guinea, and the Caribbean. But in the period under study the most dominant triangle linked England to Moorish North Africa and North America. Surprisingly, this triangle has been ignored by historians. In his magisterial study of the Mediterranean, Fernand Braudel had little to say about England’s North African/North American exposure while David Beers Quinn traced English travel between 1400 and 1600 from Iceland to the Caribbean but made no mention of the Mediterranean. These and other writers focused on the English westward venture.2 By so doing they ignored the evidence demonstrating that in the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods, not only was the eastward venture a great rival to the westward one but it was actually more successful.

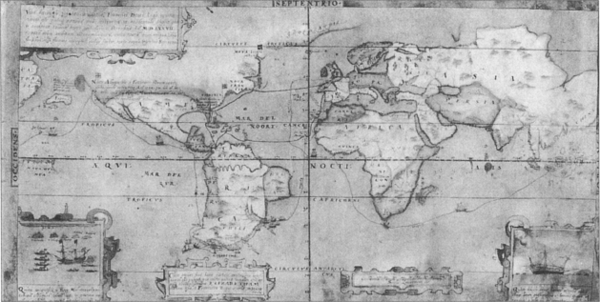

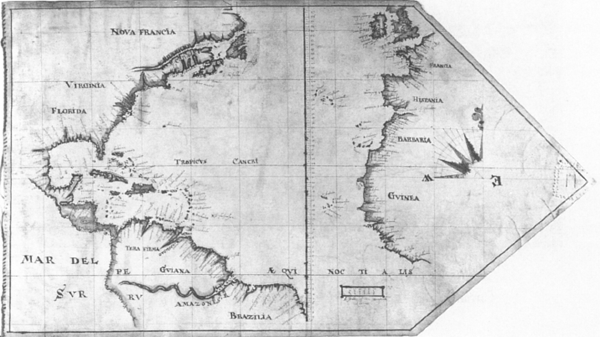

The Drake-Mellon world map, which traces Drake’s itinerary on his “famous” voyage in 1577, shows the England-North Africa-North America triangle. On his way from England to America, Drake and his fleet stopped in Morocco; John White did the same in 1590. 3 The Virginia Company Chart of the early 1600s confirms this triangle: it shows England along with its European rivals “Francia” and “Hispania;” it also shows “Barbaria” and “Gvinea” in Africa; and finally, it shows “Nova Francia,” “Virginia,” “Florida,” and “Gviana” in America. This is a map of England’s “new” commercial horizon in which America is as prominent as Barbary. Such prominence does not reduce the difference between England’s colonial attitude to America and its commercial relations with North Africa. The Virginia charter of 1606 urged the adventurers and colonists to take possesion of the land and its resources; but it was over a decade later that an ideology of settlement was implemented. Indeed, as Mary C. Fuller has shown, the period between 1576 and 1624 witnessed the “failure of voyages” to America, which was “recuperated by rhetoric, a rhetoric which in some ways even predicted failure.”4 Meanwhile, and as the previous chapter has shown, Britons “dwel[led]” among the Muslims as early as the 1580 Ottoman-English treaty. In the period which English history often dedicates to Roanoke, Virginia, the Somer Islands and Plymouth, there were more Britons going to North Africa and the Levant than to North America, and more Britons “dwel[ling]” there than in the coloniess of the New World.5

From the decade of the Roanoke debacle to the beginning of the Great Migration, the same complex impulses that motivated “vexed and troubled Englishmen” to cross the Atlantic motivated them to cross the Mediterranean too. Actually, the English had begun migrating to North Africa before they traveled to America. In 1577, William Harrison observed that “the wise and better-minded” English men and women were forsaking the realm “to live in other countries, as France, Germany, Barbary” and elsewhere.6 Later, an increase in England’s population compelled some Britons to leave for Europe and North Africa. In 1609, Robert Johnson urged his countrymen to seek the riches of the West Indies rather than risk their lives and spill their blood “to reconquer Palestina from the Turkes and Sarazens”7; Britons were being encouraged to move westward rather than eastward. Evidently two years after the establishment of the Virginia colony in 1607, there were still more Britons exploring the Mediterranean than the Atlantic.

3. Manuscript world map on vellum showing Drake’s route of Circumnavigation. Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art.

As has been shown earlier, large numbers of English and Scottish merchants and traders settled on the Muslim North African and Atlantic coasts. Meanwhile, others sailed to America, where in the early years of exploration the chief purpose of establishing outposts was to trade in fur and fish with the Indians—once it was realized that there was no gold—and to attack the Spanish treasure fleet. Many were actually more active in the latter than the former, much to the sorrow of Johnson, who lamented that John White’s Roanoke colonists had turned from planting to “hunt after pillage upon the Spanish coaste.”8 Settlement had not yet attracted the first wayfarers in America. It was not until the 1620s that “English settlement actually took root in New England.”9 Earlier travelers had no plans to make America their home: “Of a merchantlike Trade,” wrote the author of the Discourse of the Old Company in 1625, describing the plans for Virginia, “there was some probbillitie . . . but of a plantation there was none at all, neither in the course nor in the intencons either of the Adventurers here [London] or the Colonie there [Virginia].” 10 Rather, as with the first exclusively male Jamestown settlers, the goal of going to America was to grow rich by trade or pillage, and then return home. In this respect, as Britons went to North America in quest of opportunity and fast wealth, so did they seek North Africa.

4. Virginia Company Chart. Courtesy of I. N. Phelps Stokes Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Arts, Prints and Photographs, the New York Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

In fact, the attraction of North Africa was stronger than that of North America. There was more gold in the coffers of Mulay al-Mansur of Morocco than in all the lands of Powhatan, and while the former had been dubbed “the golden” after his seizure of gold-rich Sudan, the Indians of Virginia, and later of Massachusetts, cherished the trinkets the colonists gave them. In North Africa there was the certainty of gold (thus Morocco’s choice of the gold casket in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice); in America, none had been found. It is no wonder that more Britons crossed the Mediterranean and stayed in North Africa than crossed the Atlantic to America. In 1605, James I issued a royal proclamation in which he called on his subjects who were in “the Service of divers forreine States, under the Title of men of Warre …[to] returne home into their owne Countrey, and leave all such forreine Services, and betake themselves to their Vocation in the lawfull course of Merchandize, and other orderly Navigation . . . [and not] otherwise employ themselves in any warlike Services of any forraine State upon the Sea.”11 Twenty years later, in Februay of 1623, another prolcamation repeated this call, condemning the “great numbers of Mariners and Sea-faring men, [who] contrary to their duety and allegeance, and against the Lawes of this Realme, have presumed without such licence to goe abroad, and serve other Princes and States in forraine parts.”12 If these proclamations are coupled with others denouncing British pirates “within the Mediterranean Seas,” and the “protection which is given them in Tunis, Argiers, and the places adjoyning,” a considerable English/British presence can be confirmed in the North African Mediterranean that was dependent on, and in deep cooperation with, the Muslim rulers: “so great a part of our strength,” declared Robert Johnson, are “arming and serving with Turkes and Infidels.”13

While “great numbers” of Britons served foreign princes in the Mediterranean, royal proclamations about overseas colonization show that James I viewed the American colonies as no better than convenient destinations for vagabonds and undesirables. One of his first proclamations issued just months after acceding to the throne urged that rogues might be banished to “some place beyond the Seas”; by 1617, after the colonization initiative had proved costly in both lives and funding, the place was specifically identified as “Virginia.”14 For King James, the Britons among the Muslims were useful while the men to be sent to Virginia were not. Muslim North Africa was a place from which Britons had to be lured back by pardons; Virginia was a place to which unwanted Britons were to be sent.

By 1617 only a few hundred Britons had survived sickness and famine in Virginia. The situation was so desperate that lotteries were introduced in London to help revive the transatlantic enterprise. In 1618 Wolstenhome Towne was built on the James River, but disappeared within a few years, while half of the 1620 Plymouth “pilgrims” died soon after landing. Meanwhile, there were “great numbers” in the Muslim Mediterranean not only consisting of pirates, but of traders and merchants who, in the first two decades of the seventeenth century increased England’s commercial relations with the Levant and North Africa by one-third.15 Traders, pirates, and even the king viewed North Africa as more promising than North America. And as many men, such as Captain John Smith, conquered, pillaged, burnt, and built in America, and then returned to a quiet retirement in England, so did many others do the same among the Muslims. William Mellon, who was denounced in one of the Jacobean royal proclamations as an Algiers-based pirate, returned to England and found a place for himself on the Admiralty Commission.16 North America was a place, according to propagandists and colonists, in which Britons could work, explore, and then return home; and so was North Africa.

Britons may have had more reasons to seek North Africa than America. First, the journey across the Mediterranean and to the Muslim Levant was navigationally less dangerous than that across the Atlantic. There is a large number of references, especially in New England autobiographies and memoirs, about the terror of crossing the ocean.17 While the Mediterranean was not without its hazards—since Britons had to sail in winter to avoid attacks by Spanish and Maltese (Catholic) pirates—it was not as forbidding as the “Ditch” and the “raginge floods” of the “Perillous Ocean.”18 Second, in America there were swamps and marshlands, mosquitos and typhoid-contaminated water, and, most terrifyingly, hurricanes the like of which do not exist in the Mediterranean. Sir Thomas Gates compared a hurricane in the Caribbean with the storms he had encountered in the Mediterranean: “Windes and Seas were as mad, as fury and rage could make them; for mine owne part, I had bin in some stormes before, as well upon the coast of Barbary and Algeere, in the Levant . . . Yet all that I have ever suffered gathered together, might not hold comparison with this [hurricane].”19 The Mediterranean was safer and more familiar than the Atlantic. Furthermore, the Muslim cities at which traders, captives, and sailors disembarked were clean and not unattractive. Muslim society was metropolitan; Algiers was nearly as big as London, and Sanaa (in Yemen) was “somwhat bigger than Bristol.”20 Meanwhile, the regions of America, as Respire objected in Richard Eburne’s A Plain Pathway to Salvation, “are wilde and rude—no towns, no houses, no buildings there.”21 Until the 1630s there were no colonial towns in America, and colonists relied on London as their market. Although the American Indians had a complex culture, Britons did not bother to familiarize themselves with it and merely saw what they deemed “salvage” and uncivilized.22

Third, in the late sixteenth century and the first decade of the seventeenth century, numerous Britons returned from unsuccessful settlement adventures in America and propagandized against emigration. Many remembered the debacle at Sagadahoc in 1607. George Percy’s account of the “Starving Times” of 1609–1610 in Jamestown drew such a frightful portrait of the plight of the colonists that it became familiar from England to Spain. In 1612, John Chamberlain described how “Sir Thomas Gates and Sir Thomas Dale are quite out of hart,”23 and a decade later, news from Plymouth and Salem told of sickness and despair. Furthermore, the death rate in the colonies was very high: between 1606 and 1624 six colonists died for every one that lived in Jamestown, and of the women who were brought as wives in 1619, it is not clear if any survived; between 1625 and 1640 the death rate was 50 percent.24 That is why from the very beginning of Elizabethan travel to America, men such as John White, John Smith, Christopher Levett, and others, tried to refute the negative propaganda about America and to write glowingly about the fertility and attractiveness of the land; so too did some poets and masque writers who compared America with a terrestrial paradise.25 But the last years of Elizabeth’s reign and the first years of the Jacobean period witnessed so much suffering that “gloom . . . hung over the colonial prospect.”26 . Although the Great Migration in the 1630s made the English presence in America definite, colonists remained doubtful about settlements as thousands returned to England in the 1640s and 1650s.27

In the American colonies investors got good returns at the price of cheap or indentured or enslaved English, Scottish, and Irish labor. Among the Muslims, the “small men” with basic skills or with a willingness to convert to Islam were the ones to benefit. An indentured servant or dissatisfied colonist did not have much to hope for in America; among the Muslims, it was different. When William Okeley was about to escape from his captivity in Algiers in 1644, he paused to reflect on whether it was wise for him to do so since in Algiers he had work and income, while back in England he would find himself without employment and support at a time when civil war was ravaging the country.28 Many of the captives in North Africa were free to roam the cities, start their own businesses, pursue their professions, and make money, part of which they gave to their masters and part of which they saved to buy their freedom. Okeley was hesitant to give up his Algerian captivity because he had seen others buy their freedom, convert to Islam, and settle in their new identities and careers among the Muslims.

Such opportunity was not as plentiful in the plantations. An indentured servant, even after winning his freedom, could not prosper without capital. In 1666, George Alsop wondered in a letter to his brother in England whether it was not better for him to remain indentured in Maryland than to become free. In words that are strikingly similar to Okeley’s “dialogue” with himself before his escape, Alsop complained about his condition in New England: “Liberty without money,” he wrote, “is like a man opprest with the Gout, every step he puts forward puts him to pain . . . What the futurality of my dayes will bring forth, I know not; For while I was linckt with the Chain of a restraining Servitude, I had all things cared for, and now I have all things to care for my self, which makes me almost to wish my self in for the other four years.”29 For Okeley, North Africa was more the land of security than North America was for Alsop.

As has been shown, from the Elizabethan until the Caroline periods thousands of Britons were captured and then made to work—some permanently to remain on Muslim soil. Between 1603 and 1615, 100 English and Scottish ships were taken by North African pirates. Between 1616and 1620, the number is 150 ships; between 1622 and 1642 the number is 300. By the mid-1620s there were between 1200 and 1400 captives in Salee alone; between 1622 and 1642 over 8000 Britons were taken captive; between 1627 and 1640 there were 2828 British captives in Algiers alone.30 Confirmation of such high numbers appears in the eyewitness accounts of captives: in 1640, Francis Knight used the word “innumerable” for the captives in Algiers alone, and in 1642 “An Act for the releife of the Captives taken by Turkish Moorish and other Pirates” mentioned “many thousands.”31 There would have been more references to the high number of captives had records other than those of seamen and traders been kept; the previous “thousands” do not include the British convicts who were captured by Muslims while being hauled to the American penal or slave colonies. Such people did not fall within the ransom budgets or record keeping of the trading companies or the monarchy. Many English youths either ran away to the Turks or were stolen or enticed by them, as a report in 1589 showed.32 Of the thousands of Britons known to have been captured by or “emigrated” to the Muslims, the records that have survived listing their numbers and names show that “only a fraction, probably less than one-third,”33 ever returned to England. And that “fraction” would be of captives only. The emigrants-turned-Muslim, the poor and indigent who were captured by the Barbary Corsairs, and the Britons who were sold to the Moors by their own countrymen remain numberless.

Finding themselves captured or enslaved by the Muslims, many such Britons “emigrated” to the Muslim dominions by conversion and acculturalization. Interestingly, the same “emigration” occurred to America. After all, only a few of the early merchant adventurers who crossed to America had investment capital and were able to acquire land and plantations. The rest, who were the majority, were the poor and destitute. Many of the “emigrants” to Virginia and other American colonies in the Jacobean and Caroline periods—and well into the eighteenth century—were spirited men, women, and children, zealous youths, helpless vagrants, and numberless orphans who were abducted or who, under the influence of drink or fanciful rhetoric, were made to sign agreements for transportation and then locked up to await shipping. From 1607 on, “thousands of poor children were shipped off to Virginia,”34 while so many vagrants and vagabonds were viewed as naturally destined for the plantations. Francis Bacon complained in one of his essays that the plantations were being filled with “the scum of people, and wicked condemned men.”35 Furthermore, it was state policy in England to ship prisoners of war to the West Indian plantations, and after 1662 and the Act of Uniformity, to transport nonconformists and felons too.36 “Scarce any” of those brought from England, complained one, “but are brought in as merchandise to make sale of.”37 Like their counterparts who were captured on the high seas by Muslim pirates, many Britons did not have a choice about their “emigration” to America. Nor did they end up in a better condition; as Muslim captors bought and sold British captives, so did colonial masters buy and sell Britons “at any time for any period of years.”38 It is no wonder that in 1620 “one Spark” reported from Plymouth “that the people are vsed wth more slavery then if they were vnder the Turke.”39 New England conditions were as bad if not worse than conditions in North Africa.

Although the number of British “emigrants” to America remains as imprecise as that of the “emigrants” to Islam, the existing evidence shows that from the first attempt at an English settlement in 1584 and 1585 in Virginia, until the accession of Charles I to the throne and the beginning of the Great Migrationt, the number of surviving colonists was small. It did not exceed five thousand, with “half of them in Virginia and the rest precariously scattered in New England, Bermuda, Barbados, and the Leeward Islands.”40 If this figure is correct, and if the figures about British captives in North Africa are correct, then it is possible to conclude that until the beginning of the Caroline period, the number of Britons in Muslim North Africa was higher than that in North America. Similarly, if the figures of three thousand captives in Algiers and fifteen hundred in Salee in May 1626 are correct, then it is safe to conclude that the number of congregated expatriate Britons in this period was higher than anywhere else in the world—Virginia included.41 Unfortunately, it is not always possible to break down the numbers among the traders, settlers, pillagers, indentured servants, the kidnapped and captives. But it is clear that during the years Jamestown and Plymouth were being built, there were thousands of Britons among the Muslims—many more than in America.

Like their Muslim-bound counterparts, the America-bound emigrants hailed from the same areas in England and Wales, 42 that is, chiefly from the West country, London, and East Anglia. They also hailed from the same social groupings. Contrary to what Richard Slotkin has maintained, the first colonists in America were not “drawn largely from the rising Protestant middle classes.”43 Rather, as John White’s list of names shows in 1587, members of the gentry were by far fewer than the “Households of the Common Folk.” David B. Quinn has shown that the majority on White’s list were actually “servants.”44 As long as America was seen as a place for “front-line operatives,” as Cressy has called them, who worked for their masters in England, and were to return there after finishing their projects, the chief travelers were of the menial class. The list of names prepared by Edward Waterhouse in his account of the victims of the 1622 massacre confirms this view. Although there are some “esquires” and “masters” mentioned, there are many who are simply described as “his man” or “a boy” or whose full names were not known, attesting thereby to a menial status: “Collins his man;” “Robert Tyler a boy;” “–– Atkins. –– Weston;” “The Tinker,” “Master Tho: Boise, & Mistris Boise his wife, & a sucking Childe. 4 of his men. A Maide. 2 Children …. 6 Men and Boyes.”45 That is why English propaganda for colonization repeatedly called for the emigration of men with professions and craft, the implication being that those who had actually been going there were not, but were instead, as the image of the first colonists of Virginia and Barbados remained until the end of the century, “loose vagrant people” intent on “whoreing, thieving or other debauchery.”46 The majority of Britons in America were of a low socio-economic class and/or of questionable moral background. In this respect they were not unlike many of the Britons among the Muslims who were of low moral and social status too—pirates and “renegadoes” and vagrants.

Actually, Britons were caught in the Renaissance triangle, much as they might not have wanted to be. Those who reached the American colonies hoped that the new land would be for them a haven not only from the Spanish Catholics, but from the “Turks” too. America, they hoped, would be safe in a way that Protestant Europe and the seas surrounding it were not. In 1621, Robert Cushman reflected on Europe in the grips of what would become the Thirty Years War: “And if it should please God to punish his people in the Christian countries of Europe, for their coldness, carnality, wanton abuse of the Gospel, contention, &c., either by Turkish slavery, or by popish tyranny, (which God forbid) . . . here is a way opened for such as have wings to fly into this wilderness.”47 As Paul Baepler has noted, “from the beginning of European colonization in America, settlers and North African corsairs clashed.”48 In 1615, John Smith complained that the Turks had seized a ship that had been sailing from Virginia to Spain, and in 1625, William Bradford, the governor of Plymouth, recorded in his diary that Moroccan pirates from Salee had captured ships on their way to England to trade in beaver skins “almost within the sight of Plimoth.”49 There was no safety in the waters of the British Isles; nor was there in the Atlantic. Although the ocean did separate the colonists from Archbishop Laud and his “Popery,” it did not completely protect them against the “piratical Turkes.” As Andrew White crossed to Maryland in 1632, he was deeply afraid of an attack by the Turks; and rightly so since in 1639, William Okeley, along with sixty other Britons, was captured by Algerian pirates as he was crossing to Providence. In 1640, the minutes of a court for Providence Island urged the sending of a ship “with a magazine,” since the Mary had already been captured by the Turks. Again in that year, “several English ships on their way to Virginia” fell into the hands of the “Barbary pirates.”50 Three years later John Winthrop recorded that a ship sailing from New Haven to the Canaries was attacked by Turkish pirates.51 Until the end of the century, Britons on their way to New England were captured by the Barbary Corsairs. Joshua Gee wrote an account of a New Englander captured by the Muslims in the 1680s, and Cotton Mather noted in his diary of May 1698 that “wee had many of our poor Friends, fallen into the Hands of the Turks and Moors, and languishing under an horrible Slavery in Zallea” (Salee).52 In his sermon of 1700, The Goodness of God Celebrated, he mentioned that “between Two and Three Hundred” New Englanders had been imprisoned by the “Emperour of Morocco.”53 Having prepared for a westward movement to New England, these captives found themselves forced into an eastward trajectory toward Islam.

Whether Britons were compelled to go to North Africa or North America, or voluntarily chose to explore, trade with, or settle these lands, they found themselves exposed to a dynamic of relationships that tested the limits of their national identity. Confronted by the Muslim and the Indian Other, many Britons, chiefly the “small men,” chose to superimpose Muslim on English or Indian on English: they converted to Islam and “turned Turk,” or went “native.” The Roanoke survivors, if any, may have gone native, as did Thomas Weston’s band in the early 1620s. Later, Thomas Morton was accused of having transculturated into Indianness. According to historian Edmund S. Morgan, “some” Englishmen deserted Jamestown to join the Indians, while others were forced into transculturation after being captured by the Indians,54 in the same way that many Britons were forced into conversion to Islam—or at least so they claimed.55 During the Age of Discovery many Britons were willing to transform themselves, “fashion themselves,” to use Stephen Greenblatt’s term, into Indians or Muslims.

Voluntary self-fashioning, which was practiced by both Britons and other European Christians, shows that while the European aristocratic identity fashioned itself against the Other, as Greenblatt has argued, the commoner was willing to transform himself into the Other. Members of the lower classes who adopted Islam or Indianness saw no religious or cultural divide between them and the Other that they could not easily and willingly cross. And so many of them fashioned themselves into the Other that they caused deep anxiety in their home communities: for these “renegades” did not seek to destroy the Other, as Greenblatt claims in his analysis of the motivation for the invention of the Other;56 rather they became so committed to their new communities that they gave up their Christian names and adopted Indian or Muslim names. Robert Marcum, who lived among the Indians, came to be known by his Indian name “Moutapass” in the same way that Richard Clarke, for instance, who joined the Muslims, was known as Jafar.57

Such men were very self-conscious about the fashioning of their identity. After all, admission into the Muslim umma (religious community), as into the Indian tribe, entailed rituals and processions that made both the adoptive community and the adoptee deeply aware of the “artful process” (according to Greenblatt) being employed to fashion the inductee into the Other, and to confirm his commitment to the Other. Such commitment proved quite strong since the “renegades” ended up teaching the non-Christian adversary a lot about European technology. For many Britons, the crossing of the boundary between London and Istanbul or Algiers proved tempting—although perhaps less difficult—than leaving Jamestown or Charlestown to the Indian hinterland. Crossing to the American Indians ensured survival at a time of famine in the colonies, and perhaps secured a consort in a community sorely lacking in women; crossing to the Muslims could produce wealth and power.

Britons and other Christians crossed over to Islam and to Indianness so much so that the term renegadoe or runnugate, which in 1599 represented to Hakluyt a convert to Islam, was soon applied to Britons who went native in America.58 But more Britons converted to Islam than to Indianness because after 1622 the Indian was confirmed as a wild and violent creature. From then on, even those who were captured by the Indians, as Vaughan and Clark have shown, “successfully resisted efforts at assimiliation by the French and Indians.” The number of New Englanders who deserted their families and villages from the 1620s on to settle among the Indians was very small.59 Only those who were captured as children or youths between the ages of seven and fifteen completely integrated into Indian life and rarely sought to “return” to their racial community.60 Meanwhile, in every decade of the Elizabethan and Stuart periods there were Britons who embraced Islam.

It is clear that from the Elizabethan until the Caroline period, Britons found themselves in a triangular relationship between their own country, North Africa, and North America. In that age of English discovery, more Britons went to North Africa than to North Amercia, and more Britons crossed over to Islam than to American Indianness. Although America later superceded the Muslim Levant and North Africa in social and economic importance to England, in the age of Hakluyt and Purchas, the Golden Hind and the Mayflower, the Muslim world attracted more travelers, pirates, traders, and settlers than New England, Virginia, or the Caribbean.

For the majority of England’s adventurers and seafarers, the Mediterranean and North America were the only locations where they could explore, fight, pillage, or live. Just as the age was one of discovering new geographical horizons, it was also one of expanding commercial markets, pursuing new careers, or exploring the different territories of the triangle. In the 1560s, Thomas Stukley decided to establish a kingdom in America to be independent of Queen Elizabeth, as he told her to her face. Over a decade later he died fighting with Moroccan forces against a Moroccan-Turkish-Spanish alliance in the battle of Alcazar. From England to the Americas to his final resting place in North Africa, Stukley lived and died in the new geographical triangle. Similarly, men such as the traveler George Sandys, the explorer William Strachey, the diplomat Sir Thomas Roe, the colonist Ralph Lane, the adventurer John Smith, the founder of New Jersey George Carteret, and others were in the Levant before they crossed to the Americas—in the case of Roe it was the other way round—again exploring the Age of Discovery’s triangular options. Richard Hawkins, one of the foremost Elizabethan sea dogs, plundered the coast of South America before returning to England and serving against the Algerian pirates. In 1597, Sir Anthony Shirley came into possession of Jamaica, but left it, sailed home, and from there ventured to the Levant and Persia.61 John Pory translated the work of Leo Africanus, one of the most influential and informative texts about North African Muslims in Renaissance England, and then went to Virginia and wrote about it; Sir Thomas Smythe was a founder of the Levant Company before becoming treasurer of the Virginia Company; four members of the Levant Company were also members of the Massachusetts Bay Company.62 William Davis, a surgeon on the ship London, sailed in the Mediterranean until he was captured and enslaved by the duke of Florence and sent as a galley slave to South America. John Harrison was the English agent in Morocco before becoming governor of the Somer Islands in 1622—and three years later, King Charles’s emissary to Morroco again. Captain John Smith’s coat of arms, which appeared in his books about Virginia, showed the heads of three Turks he had killed, or claimed to have killed, in personal duels during his soldiering days against the Ottoman army in central Europe—much like the coat of arms of John Hawkins had shown “a demi-Moor” too.63 In New England, before Cape Ann was known by that name it had been named by Smith “Cape Tragabigzanda . . . after his imaginary Turkish lady love,” and across from Cape Cod he named three islands “The three Turkes heads.”64 Even the topography of Indian America recalled the Muslim Levant. Sir Thomas Arundel, who financed George Weymouth’s attempt to locate a Northwest passage, had fought the Turks and been named a count of the Holy Roman Empire in 1595; the father of Sir Ferdinando Gorges, Sir William Gorges, had fought the Turks in Hungary in the 1560s.65 Before many of the early “adventurers” went to America, they or their kin had ventured eastward among the Muslims. Before John White drew Indians, he had drawn Turks and Levantines; before the Mayflower carried the so-called “pilgrims” to Plymouth, it had traded in the Muslim Mediterranean. By the 1620s, ships were carrying tobacco from the colonies “at easie rates into Turkie Barbarie,” and in the 1650s, Andrew Marvell’s colonists celebrated Bermuda with images of the Levant: “With cedars, chosen by his hand, / From Lebanon, [God] stores the land.”66 Colonists, trade, and ships linked North America to North Africa.

Finding themselves operating within the Europe-North Africa-North America triangle, the English turned to the example of Spaniards, who had pushed their reconquista of the fifteenth century into a holy war of occupation of North Africa in the sixteenth century, while pursuing the colonization of the Americas. As Britons thus launched their merchant adventurers they encountered the Spaniards as their chief European adversary and model; while Raleigh and Drake fought with them, Hakluyt included the works of some Spanish explorers of America in his Navigations. The Spaniards had partly defined their national identity through their encounter with the Moors and then the American natives. Because they had been well informed about the Muslims and their history, if only because they had been fighting them for centuries, once they began the conquest of America they applied their constructions of Muslim Otherness on the American Indians.67 Although Amerigo Vespucci at the end of the fifteenth century was not inclined to compare the Indians with either the Jews or the Moors—they were far worse than these two groups—subsequent Spanish writers did not hesitate to link the “Moors” and the “Saracens” with the Americans, as can be seen in the writings of Da Verrazano, whose work was available to English readers in Hakluyt. Joseph d’Acosta compared the nomadic life of the Central Plains Indians with the “wilde Moores of Barbarie called Alarbes,” while de Coronado repeatedly allied the Indian with the Turk in his account of his expedition of 1541 and 1542. 68

Seeing that Spaniards superimposed Muslim on Indian, and recognizing in that superimposition a moral and epistemological function, Britons followed the Spaniards in the superimposition as well as in its inversion—Indian on Muslim. Such interchangeablity of models was possible for Britons because they “discovered” the American Indians at the same time they “discovered” the Muslims—real Muslims, that is, as opposed to Muslims in medieval romance and polemic. The encounter with and the “discovery” of the two peoples, whether in geographical books or on the ground, was simultaneous: the first English book on America by Richard Eden, thought to have been published in 1511, included information about “greate Indyen” and “Arabia.” These references to Arabia were not fortuitous, for as Hakluyt reported at the end of the century, it was in that year England had begun sending its ships to trade in “Tripolis and Barrutti in Syria,” thereby showing the “antiquity of the trade with English ships into the Levant.”69 The second English book on America, Eden’s translation of Sebastian Munster, introduced the English audience to the Muslims of the East Indies and, rather interestingly, presented them in a more favorable light than Indians of the West Indies.70 The third English book on America, Eden’s translation of The Decades (1555), included “A breefe Description of Affrike” in which reference was made to “Tunnes, Bugia, Tripoli . . . Marrocko, Fes.”71 In Andrewe Thevet’s The New Found Worlde or Antarctike (translated from French in 1568), allusions to the “Turkes” and “Moores,” and to “Barbaria” and “Mahometists” are interspersed throughout the descriptions of “India America.” In the next half century and beyond, Hakluyt’s and Purchas’s numerous editions of their geographical works brought the dominions of Islam—both in the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean—into the English reading experience at the same time that the Americas were being introduced.

Historians have recognized that Hakluyt and his successor were responsible for creating the momentum for the westward migration, but those writers/compilers were also instrumental in providing information about the Muslim dominions in North Africa, central Asia, and the Far East. The expansion of the unit on the Muslim world between Hakluyt’s first two editions of The Principal Navigations is noteworthy in that the first part of the 1589 Navigations, which covers the Asian and African domains of Islam, falls between pages 1 and 242; the third part, which covers America, falls between 506 and 825. The second volume in the second edition of 1599 and 1600 included two parts about the Muslim world—the first in 312 pages and the second part in 311 pages; the third volume focused on America in 866 pages.72 Similarly, the expansion of the Muslim unit in Purchas’s Pilgrimage (1613 and 1617 editions) and Pilgrimes (1625), the last significantly produced under the patronage of and with a subsidy from the East India Company, attests to an interest in the Levant that was as pervasive among English authors and readers as that in America.73 North Africa and North America became part of English knowledge in the same decades and in the same texts.

Also in the same period, Britons began to meet physically with both the American Indians and the Muslims—not only in North America and North Africa respectively, but in each others’ continents. They met American Indians in North Africa as slaves who had been carried across the Atlantic by the Spaniards and the New Englanders and sold into the Muslim markets; as late as 1691, Indians who had been captured during King Philip’s War were “sent to be sold, in the Coasts lying not very remote from Egypt on the Mediterranean Sea.”74 Britons also met Levantines in the Mediterranean who were on their way to the Americas, as was the case with the first Arabic writer to leave an account of his sojourn in Spain’s American empire in 1668, and who used an English ship to travel from the Levant to Spain in order to make the Atlantic crossing (see appendix B). Britons also met Moorish and Turkish captives of Spain in the Caribbean. In March of 1586 some Moors deserted to join Sir Francis Drake during the English attack on Cartegena, and later during the attack on Santo Domingo. In June of that year Drake captured hundreds of “Turks and Moors, who do menial service” in Havana.75 Although the Moors the English encountered in the Caribbean were slaves who projected weakness and despair, they were subjects of rulers whom England’s queen wanted to befriend, and whose assistance she sought against Spain. There must have been so many of these Moors in the American Spanish dominions that in 1617, Purchas mentioned that Islam had spread as far as America. Purchas was probably thinking of these captives, some of whom had been freed by their Spanish masters and were settled in the colonies.76 (In 1658, William D’Avenant wrote The Play-House to be Let, in which he included a scene about “the Symerons,” a Moorish people brought formerly to Peru by the Spaniards.)77 Purchas could also have been thinking of an ethnological theory that described the American Indians as descendants of the Moors of North Africa.78 Clearly an English writer who was familiar with Muslims remembered and superimposed them on the American Indians while another who was familiar with American Indians remembered and superimposed them on the Muslims. Neither group was perceived autonomously—each was a predicate of the other, although they originated half a world away from each other.

Such superimpositions repeatedly appear in the writings of colonists and travelers. William Strachey recalled the “Turks” when he saw that the Indians drank water instead of beer, as the English did, and spread a mat at the entry of a distinguished guest. The Powhatan, noted Strachey, executed malefactors by having them “beaten with Cudgells as the Turks doe,” and he married many wives he did not keep in the same house “as the Turke in one Saraglia or howse.” The Indians danced in “frantique and disquieted Bacchanalls,” resembling the “Daruises in their holy daunces in the Moschas vpon Wednesdayes and Frydayes in Turkey,” and Indian men did not “haue those sensuall helpes (as the Turkes) to hold vp ymoderate desires.”79 For Strachey, understanding the Indians was partly predicated on his having observed the Turks. Similarly, John Smith compared what he saw among the Americans with the Tartars and the Turks, and linked together for his readers the two geographical and ethnographical directions of English enterprise. In the table of contents of his The True Travels, Adventvres, and Observations (1630), he indicated that he would describe the religion and “Living” of the Turks, and immediately following, he offered “a continuation of his generall History of Virginia.”80 For John Smith the two worlds seemed complementary, and although he advocated the Americas for colonization, he presented the world of Mediterranean Islam as a domain of adventure and exotic allure.

As a result, many of those who praised him or his work in dedicatory poems came to see the two worlds together. “In Climes vnknowne, Mongst Turks and Saluages,” wrote his cousin N. Smith in 1616, Smith had labored “T’inlarge our bounds.”81 In 1624, a “Benefactor to Virginia” praised Smith:

By him the Infidels had due correction,

He blew the bellowes still of peace and plentie:

He made the Indians bow unto subiection,

And Planters ne’re return’d to Albion empty.”82

In the complimentary verses to The True Travels, Adventures, and Observations, Richard Meade, a friend, praised Smith for having combated “with three Turks in single du’le” and then “found a common weale / In faire America.” Another friend, M. Cartner, praised him for having explored the “Westerne world” after having achieved “a Captaines dignity” among the Turks.83 Even his epitaph alluded to his “service” in fighting the Turks and his “adventure” among the “Heathen” in America.84 The two non-Christian angles of the Renaissance triangle were within the covers of the same English book. The vis-à-vis of the English reader was the Turk and the Indian.

Peter Hulme has correctly observed that as England began its imperial thrust into America, it used its repository of “images and analogies” from its classical knowledge of the Mediterranean, and applied them to America. “The discourses of the Mediterranean were . . . adequate for the experience of the Atlantic.”85 Such a statement must be broadened to include the discourse of the Muslim Mediterranean—particularly in the Elizabethan and the Jacobean periods—when Britons were still trying to come to terms with the Indians, and could do so only by comparing them with the other non-Christians close to home. While Herodotus may have informed English readers about the Persians and the Egyptians, and Homer and Virgil about the Graeco-Roman Mediterranean, as Hulme has argued, it was the Turks and Moors who provided the most immediate parallel to the Indians.

Hulme’s statement must also be inverted: in the process of encountering the Muslims, English writers employed their categorization of the Indians to define the Muslims. This two-way superimposition can be seen in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, where the island where the events take place serves, as Hulme has stated, as a “meeting place of the play’s topographical dualism, Mediterranean and Atlantic.”86 But how could the Atlantic be superimposed on the Mediterranean? As Hulme continues, Caliban shows the superimposition of the American Indian imagery of a gullible, ugly, cannibalistic, treacherous man onto a Mediterranean “wild” man. This “wild” man, however, is not of the “pedigree that leads back to [Polyphemous in] the Odyssey,” as Hulme explains. Rather, Caliban’s pedigree is the “wild Arab” or the “wilde Moore” whom travelers and dramatists repeatedly described and denounced.87 The Muslim and the Indian were hybrid products of two different cultural encounters that were forcefully yoked together.

This yoking was steeped in anxiety because English writers and strategists recognized, from the first establishment of the Turkey Company until the Great Migration and well into the rest of the seventeenth century, that their colonial ideology was winning against the Indians but losing against the Muslims; they were enslaving Indians while Muslims were enslaving them. In North America, Britons and other Europeans developed an ideology that placed them at the center of God’s plan for history. They were to replace the old and the wild with the New and the English or British—thus “New England” and “Nova Britannia.” But in the dominions of Islam they had an experience that turned their colonial projects upside down. It was devastating for a Briton, or any other European, on his way to America to find himself, perhaps along with his family, captured by the Muslims and brought to Algiers, Salee, or Tunis as a slave. Instead of fashioning the American “salvages” after his image, the English, Welsh, or Scottish captive found himself being fashioned after the Muslims—eating their food, learning their language, adjusting to their religious customs, and wearing their clothes and turban. In America Britons imposed themselves on the Indians, but among the Muslims they were forced to adjust and recognize the Muslims on their own “infidel” terms.

This adjustment appears in language. In America the colonists did not bother to learn the Indian language(s), unlike the many Britons who mastered, and knew they had better master, the language(s) of the Muslims. In America the colonists held a monologue with the Indians in which they talked to them and at them and recorded what they wanted to hear the Indians saying—or else they listened but did not understand what they believed was meaningless chatter. Initially, individuals were sent to live among the Indians to learn their language, as Edward Waterhouse reported in 1622 about “one Browne,”88 while promoters such as Hakluyt, John Smith, William Strachey, and William Wood wrote lists of words with their English translations for the “delight” of the readers, “if they can get no profit.”89 But after the 1622 Indian attack, colonists gave up on learning Indian languages, which became the exclusive provenance of evangelists such as Roger Williams, or of dramatists who ridiculed the barbarity of the Indians’ speech, as Philip Massinger did in The City Madam. Meanwhile, many Indians learned English in order to serve the colonists, and often so thoroughly adopted the English identity that they willingly fought against their fellow tribesmen; Wequash and Wuttackquiackommin, who led English colonists in their massacre of Pequot Indians, are examples.

In North Africa, however, or in other parts of the Muslim Empire, it was Britons who learned Arabic and Turkish—often, but not always, after converting to Islam. Furthermore, English ambassadors sometimes addressed the Muslim rulers in Arabic (Spanish and Portuguese were also used), while the rulers wrote in Arabic to the monarchs in London. A letter sent by the Moroccan ruler to Queen Elizabeth in 1579 included the following post scriptum: “Here goeth another letre of ours, written in our languish Arabiya the which copie is this; and if ther be any that can rede and entarpret, you may se what it doth declare; yt goeth in still and orderlie, which we usede on kynge to another.”90 Muslim rulers were punctilious about the proper use of language in royal communication. That is why interest in the study of Arabic grew in Stuart England, while the work of continental Arabists generated such enthusiasm that chairs of Arabic were established at Oxford and Cambridge in the 1630s.91 It was not only punctiliousness, though, but accommodation that motivated Britons to learn the language(s) of the Muslims. Even Cromwell, who had the first navy that effectively confronted the Barbary Corsairs, realized that in peace-time he had to treat the Muslims on their own terms; he had to make appropriate concessions to a power he needed economically and did not want to antagonize militarily. Thus, in his correspondence with the North Africans, he used the Muslim calendar: “We received two letters from you,” he wrote to Hamet Basha, “dated both on the third day of the second moon of Rabia, in the year 1066, according to your account.”92When dealing with the Muslims, Britons followed Muslim rules; when dealing with the Indians, they followed and imposed their own. When they did not follow Muslim rules they found that they paid a heavy price: in 1662, the Dutch ambassador reported that the “English have been cheated in Lawson’s treaty with Algiers and Tunis through ignorance of Turkish.”93 Britons knew they had to learn the languages of the Muslim Empire if they were to succeed in their trade and alliances, for there were no Muslim equivalents to Squanto or Samoset.

The English knew that they, along with the Venetians, the French, and the Dutch, were mere salesmen who, for purposes of improving trade and alliances, bribed and connived and endured all forms of humiliation. Although Britons developed extensive commercial dealings with the Levant and North Africa—chiefly but not solely in the form of investments, which by 1656 were reputed to be over four million pounds—these investments were not modes of economic control and leverage. They were not protected by armies and military superiority but were at the mercy of the Turks who, if provoked, could confiscate the money and ruin the traders.94 In The Glory of England (1618), Thomas Gainsford described the humiliation of many English merchants and representatives by the Muslims: “our Consull at Alexandria,” he wrote, was hanged; “diuerse” were imprisoned in the “blacke Tower” and “our slaues” were all committed to the “gallies without respect of persons.”95 In his letters to Sir Thomas Roe, George Lord Carew also described the violence that was committed against the English by the Turks, both by government officials and pirates. He concluded one of his intelligence reports by stating bluntly: “As for the harmes the Turkishe piratts do vnto our nation, no restitution or justice cane be had.”96

No retaliation against the Muslims was possible in the manner it would have been carried out had the perpetrators been Indians. When the Pequot Indians defied the English colonists in 1637 they were massacred and subsequently disappeared from the Indian theater of action. Coincidentally, that same year, the English fleet attacked Salee and reduced the number of Muslim pirates there. A year later, pirates were back with a vengeance. It is no wonder that as soon as the American Indian was brought under control, Britons and other Europeans proceeded to invent him as the Noble Savage and the Edenic Indian; once he was domesticated or annihilated he could safely be imagined in a favorable manner.97 No similar “innocent” invention of the Muslims occurred in Renaissance English writings; the Muslim ability to capture thousands of Britons and create an impact on English national politics in the Elizabethan and Caroline periods could not help but enforce an image of power.98 Nor did English writers attempt to link Muslims, as they did the Indians, with the Lost Tribes of Israel and therefore bring them into the fold of biblical history. The Muslims could not be domesticated because Britons knew them for what they were—descendants of Ishmael, as the Book of Genesis had told them—and where they were. They shared with them the same European continent and the same Mediterranean, Atlantic, and Channel waters, and unlike the American Indians, they had reached the seas surrounding the British Isles.

Muslims were close to the Britons’ home, and they were not “going away,” as were the American Indians—at least those who survived the plagues, famines, and massacres—who surrendered to the English colonies and lived the rest of their lives in despair and starvation. Nor were the Muslims turning English, as the Irish and Welsh were being forced to do. No Turkish prince was like the Indian “Prince of Massaquessts” who “desired to learne and speake our Language, and loved to imitate us in our behaviour and apparell and began to hearken after our God and his wayes.”99 There was no equivalent to the Henrico College proposal in Virginiia, nor to Harvard College’s charter to educate “English and Indian youth of this country in knowledge and godliness,”100 simply because no Muslim youth wanted to become English.

As a result of their inability to bring the Muslims within their parameter of intellectual and colonial control, English writers turned to the discourse of superimposition, whereby they yoked the defeated Indian to the undefeated Muslim. Mitchell Robert Breitwieser has noted that puritan representation of the American Indians “was particularly adept at subduing fact with category.”101 Similarly, English—not just puritan—representation of the Muslims was adept at subduing facts to categories of polarization and antipathy. Only such a juxtaposition of representations can explain why Muslims were transformed into such an Other at a time when they were having extensive diplomatic, commercial, and intellectual engagements with Britons. If “experience did not alter the Puritans’ assessment” of the Indians,102 then neither did it alter the English image of the Muslims. The stereotypes established by writers and tale tellers about both the Indians and the Muslims were not destroyed by the evidence advanced by trade, bilinguality, socialization, cohabitation, and even sexual familiarity. Evidence did not change constructions. Rather Britons classified the American Indians and the Muslims within devised categories—categories that were syncretic and interchangeable, and that totally disregarded geographical, ethnographical, and military differences. “If this be not barbarous,” wrote the anonymous author of Hic Mulier, a 1620 tract protesting the rights of women, “make the rude Scythian, the untamed Moor, the naked Indian, or the wild Irish, Lords and Rulers of well-governed Cities.”103 By lumping the whole “uncivilized” world indiscriminately together, the author failed to understand the Other. But then this writer must have believed that this was the best way to deal with the Other.

With their assured sense of Christian election, English writers imposed a total separation from, and a moral sanction against, the uncivilized Other. The commerce, alliance, and cuisine that frequently marked the interaction between themselves and the Muslims and the Indians could not overcome Otherness—an Otherness that was repeatedly represented by reference to deviant sexuality, “sodomy,” and defeat in a divinely legitimated war, a “Holy War.” These were the two templates the Spaniards had used in their conquest of America. And they were the templates English writers adopted to justify their own conquest of the Indians. As the confrontation with Islam loomed, Britons recognized that there would be no conquest of the Muslims. But as writers between the 1570s and the 1620s “recuperated the [failed] voyages” to the New World in print (to use Mary C. Fuller’s terms), so did they, in the same period, recuperate the confrontation with Islam in writing. With the two templates they had adopted from the Spaniards and with which they had justified their conquest of America, English writers turned to recuperate, in print, the conquest of Islam.