Nowadays we constantly hear or read about space shuttle flights, new satellites being launched, and spacecraft travelling to distant planets, like Mars. We probably think how easy it must have been to travel to the Moon. We know that the astronauts landed on the Moon safely and returned to Earth.

It wasn’t like that at all.

The Apollo 8 mission had shown that man could get to the Moon. But could a spacecraft land there? Would it sink in the dust, or crash on the rocks? Even if it landed safely, could the astronauts take off again? It takes enormous power to lift a spacecraft into space — so many craft had blown up when taking off from Earth.

Each astronaut knew that they might die in space, or be marooned on the Moon, unable to return. Speeches had been prepared for President Richard Nixon and other public figures in the Apollo program, to read to the world if this happened. Also procedures had been organised to cut off television links in case of disaster, so that the world would not watch the death throes of gallant men.

The astronauts knew they might die out there. Their craft might explode before they even left Earth’s gravity, as had others before theirs. A fire in space might kill them before they even reached the Moon. They knew that only the tiniest parts of the Moon had been surveyed and never in detail. They might reach their destination, but could they even return?

Yes, the Apollo 11 crew returned home safely. But throughout the mission we knew that astronauts were going where no human being had been before and that if one person, or one single piece of equipment failed, the whole operation would as well.

I was in the centre of the excitement when it was announced that Apollo 11 would attempt a lunar landing. We worked overtime for weeks installing and testing new equipment. Newspapers, and television and radio stations bombarded us with questions as the days counted down.

Honeysuckle Creek wasn’t going to coordinate the moon landing — that would be done from Mission Control in Houston. We weren’t going to be the ones to relay the first pictures of an astronaut walking on the Moon — that would be Goldstone’s job in California. The moon walk was scheduled for a time when Goldstone, not Australia, would have a clear line of sight to the Moon.

Every one of us would have loved to be in ‘real time’ communication with the astronauts as the first human foot stood on soil that was not Earth’s. But we accepted that this was not to be our role. The timetable had been carefully arranged so that the United States, who had funded and organised this leap beyond all that humanity had known, would see it first.

But the giant antennas of both Honeysuckle Creek and Tidbinbilla would each track one of the spacecraft — the command module and lunar module. We would listen to the astronauts, monitor where the spacecraft was and what it was doing, establish video links and process medical information, and then transmit all this information to Mission Control.

Every tracking station across the world had a vital role to play, and each one of us working at Honeysuckle Creek was thinking: what if my piece of equipment fails and causes this, of all missions, to be aborted or worse, the loss of the astronauts?

We worked 16 days straight, in 12-hour shifts — exhausting, but incredibly exciting. Public visits to the tracking station were restricted. No-one talked of failure, but we were all aware that the technology was still fragile and that mistakes were possible, despite careful planning and endless practice runs or ‘simulations’.

Apollo 11 astronauts leave the Kennedy Space Center’s Manned Spacecraft Operations Building during the pre-launch countdown.

NASA

The teletype machines chattered away continuously with administration messages, station status reports, operational instructions and documentation updates, last-minute engineering changes, mission countdown status reports and oodles of official NASA press briefings.

The teletype operators delivered endless wads of paper to every section of the station. Documentation clerks cut and pasted the latest updates into the many copies of an extraordinary number of operational documents, from the mission flight plan down to the local equipment operating procedures.

All through early July we checked — and rechecked — and checked everything again.

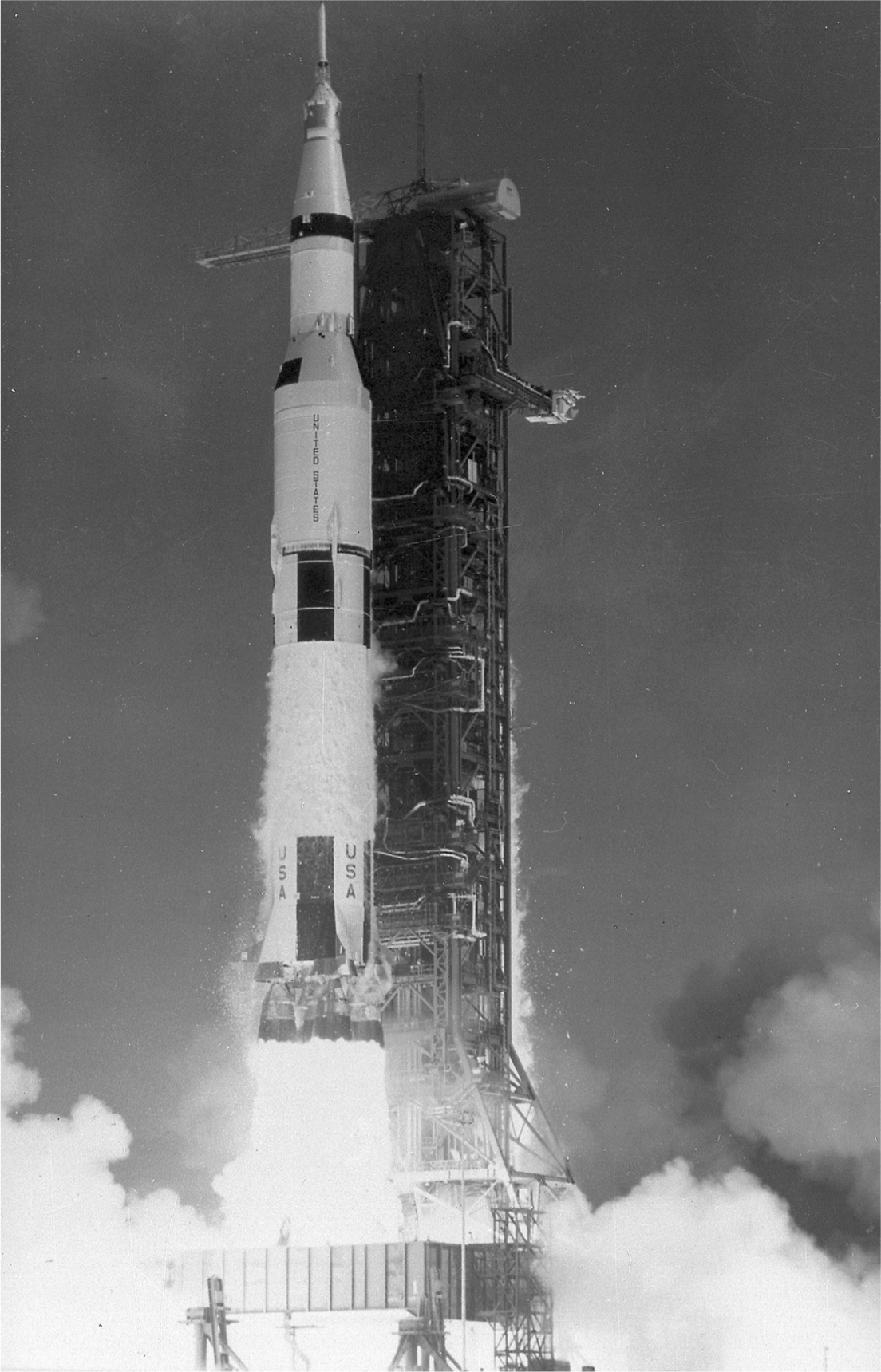

On 14 July 1969 — two days before lift-off — countdown activities intensified. Early on 16 July the giant Saturn V rocket was filled with fuel and technicians in the United States began the final check of all equipment on the spacecraft. The three astronauts — Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins — had a pre-dawn breakfast (orange juice, scrambled eggs, coffee, toast and steak — having a steak breakfast was an astronaut tradition).

After they were wired with medical sensors and communication equipment, they pulled on their long underwear, stepped into their spacesuits, put on their helmets and checked for leaks. (With their helmets on, the astronauts could not hear anything around them.) The transfer van drove them to the launch site where they rode the lift up to the hatch of the Apollo 11 command module atop the giant Saturn V rocket.

Once inside, the astronauts lay on their couches. They were strapped in and then connected to the spacecraft’s life-support and communication systems by the waiting technicians.

There, they waited for an hour and a half until lift-off. The world waited with them.

WHAT TIME DID THE ASTRONAUTS USE?

The astronauts used Houston Daylight Saving Time, as Houston in the United States was the centre of operations. But ‘mission time’ — Ground Elapsed Time, or GET — was measured from the moment of lift-off. For example, when Apollo 11 had been launched for 12 hours, 37 minutes and 15 seconds, the GET was 012:37:15.

In 1999 an asteroid-hunting telescope found a 50-metre chunk of rock circling the Sun in an orbit close to Earth’s. Scientists concluded that it was probably a chip off the Moon.

When meteors collide with the surface of any planet, or moon, the impact breaks pieces off the surface — anything from large chunks to fine dust. The Moon’s low gravity makes it easy for the impact of a meteor to blast debris into orbit — about a dozen small meteorites from the Moon have already been found on Earth.

The Saturn V launch vehicle for the Apollo 11 mission lift-off at the Kennedy Space Center.

NASA