They had one chance, and one chance only. If Eagle’s first attempt at landing on the Moon didn’t work they would have to return to the command module. There wasn’t enough fuel for a second attempt. If anything failed, the astronauts had only the Moon below them — cold or blindingly hot, waterless and airless, with human help months or even years away.

And something did fail — five minutes after the Eagle left Columbia a warning light flashed on the spacecraft’s console. The computer was overloaded — simply too much data was coming in for it to process! Another warning light flashed, this time threatening to end the descent and return the crew to the orbiting command module. Could they continue?

At Honeysuckle Creek we were all listening intently on our headsets to NET 1.

Finally Houston answered: yes, they could continue. Mission Control could process all the information needed. The lunar module Eagle sped on towards the Moon.

There were no seats in the lunar module. Armstrong and Aldrin stood — or floated — held in place by elastic cords attached to the floor. For 16 minutes they looked through the windows and timed the passage of landmarks below them across a scale marked on Armstrong’s window to confirm the tracking data that Houston was receiving.

Neil Armstrong was the pilot, but the onboard computer, with Earth backup, did most of the work. Once the lunar module swung into an upright position and prepared to land, Armstrong would take over.

Several times the computer flashed its ‘overload’ message again — it was still receiving more radar data than it could cope with — and there were also short losses of communication with Earth.

Then, just three minutes before the Eagle was going to land, Buzz Aldrin turned on the rendezvous radar as his checklist required. The computer, its capacity tiny compared even to laptops today, overloaded. The alarm sounded.

Should the entire mission be cancelled?

Only one young computer programmer, an MIT graduate, truly understood the software, because he had worked on it with Margaret Hamilton, the director of software engineering for Apollo. She was Director of the Software Engineering Division at MIT, and would become the founder and CEO of Hamilton Technologies, Inc., developed around the Universal Systems Language based on her research. On 22 November 2016, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her work leading to the development of onboard flight software for NASA’s Apollo Moon missions.

But it took a long time for her to get that recognition. (See the book Hidden Figures for more of the astounding women of the space program, especially the African-Americans who were not even allowed to use the ‘white’ toilets in the main building — until they became too indispensable to ignore.)

Back then, however, the women who contributed to the Apollo program were not given direct credit. So every eye turned to him.

He turned around, his thumbs up. GO!

With only seconds remaining, Mission Control trusted that he was right. The Eagle should continue.

And then Neil Armstrong looked out the window. They were supposed to be heading to a safe, smooth landing site. Instead, the computer was taking them to a stretch of giant boulders on the edge of a crater the size of a football field. There was no way they could land there safely! They’d break the engine casing or one of the struts and never be able to lift off from the Moon.

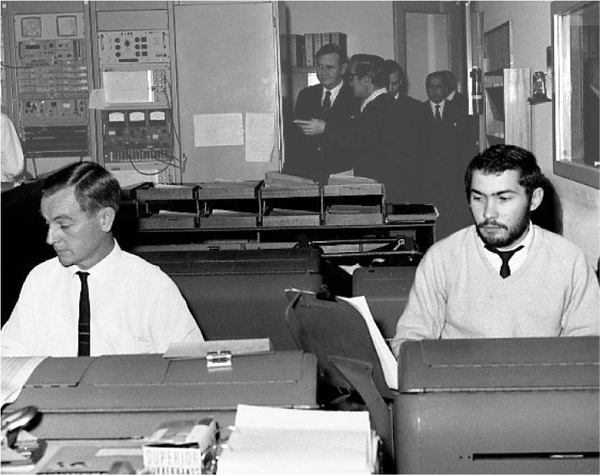

The Communications Room on the morning of Neil Armstrong’s moon walk. Prime Minister Gorton is at the back looking at the teletype operators. Vic Burman (left) and Fred Hill sending messages to the USA.

HAMISH LINDSAY

Neil Armstrong switched from computer to manual control. He began to fly the landing craft like a helicopter, past the craters and the boulders. Buzz Aldrin read the computer output aloud, giving Armstrong their altitude, their rate of descent and their forward speed.

At Honeysuckle Creek no-one knew what was happening, neither did anyone at Mission Control. Why hadn’t the astronauts landed? Armstrong and Aldrin did not have time to explain on NET 1 about the crater and the boulders.

The Eagle was consuming more fuel with every extra second! If they didn’t land in a few minutes Mission Control would have to give the order to abort, to return to the safety of the command module.

Humankind had come so far! Would the astronauts need to abort when they were only metres above the lunar surface?

Seconds dragged by. We waited to hear the order to abort. The Eagle had just 60 seconds of fuel left! The warning from Mission Control to the astronauts crackled through our headsets, while the warning light flashed on the spacecraft’s console.

But the Eagle was almost down! The blast from the engine thrust sent dust billowing over small rocks and craters.

The Eagle hovered, trying to find the smoothest place to land. I heard Mission Control calling out the time remaining before the landing craft would crash to the surface: ‘60 seconds . . . 50 seconds . . .’

Forty seconds . . . but they were down! Neil Armstrong shut off the engine. After all the worry of the previous few minutes the landing had been so smooth that Armstrong and Aldrin had to check the sensors to make sure that they really had landed.

(They later discovered that they’d had about 45 seconds of fuel left, rather than 40 — the fuel gauge wasn’t quite accurate. It was a very, very close call.)

Slowly the dust settled around them.

‘We copy you down, Eagle,’ said Houston.

Neil Armstrong replied, ‘Engine arm is off. Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.’

Houston called back to him, ‘Roger, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot . . . Be advised there’s lots of smiling faces in this room and all over the world. Over.’

Armstrong said, ‘Well, there are two of them up here.’

And at Honeysuckle Creek we were grinning too.

The crew of Apollo 11 thought they had brought ‘moon soil’ back to Earth, so scientists could study what the moon was made of, and possibly work out how the moon and Earth formed. But what did they really bring back?

Most meteorites that fall towards Earth burn up in our atmosphere. But because the Moon has no atmosphere to protect it, the surface is continually bombarded by tiny meteorites.

Every time a meteorite hits the Moon it blasts out a small crater and sprays out soft dust. This dust is packed down until it gets denser and denser — imagine very, very fine sand on a beach that has been flattened by wave after wave. This fine, densely packed dust blew up when the Eagle landed; it also made shoving the flag into the Moon’s surface very difficult. The dust was so tightly compacted that when Buzz Aldrin tried to take a sample of moon ‘soil’ he could only hammer the hollow tubes in a few centimetres.

Buzz Aldrin did bring back ‘moon soil’, but it is probably very different from the soil, rock and minerals deeper down.

WOULD APOLLO 11 SINK IN MOON DUST?

Early astronomers thought that the ‘seas’ on the Moon might be made of layers of dust from the eroded hills. These ‘seas’ could be three kilometres deep — any spacecraft landing there might sink and disappear forever.

Then the unmanned Surveyor missions actually landed on the Moon and tested the surface. The places tested only had a shallow layer of dust. It appeared to be safe for human beings to land on the Moon. But no-one could be sure, and the exact spot where Apollo 11 would land had not been tested.

Apollo 11 was truly a voyage to the unknown. Even if they could land safely, deep dust or an uneven surface might mean they could never return, stranded in that barren landscape till they died from lack of oxygen.

THE LONE WOMAN IN THE CONTROL ROOM

Among all the almost 500 male faces in the Kennedy Space Center during the Apollo 11 mission there was a single woman. We now know — finally — how many women worked behind the scenes (the credit for their work often given to men), and how, without their genius and dedication, the Apollo Program would never have been successful.

But who was this one woman the media were allowed to see that day?

Her name was JoAnn Morgan, a 28-year-old instrumentation controller. She had begun working for NASA as an engineer’s aide during her summer holidays from the University of Florida. There were few female engineers in the 1960s — in much of the USA and Australia it was still extraordinarily difficult for a woman who wanted to be an engineer to be admitted to many engineering courses, to overcome the prejudice of male students and teachers, and then get a job once she had graduated. The women who succeeded had to be determined. But by Apollo 11, JoAnn Morgan was working as a senior mission controller.

But despite that, she still sometimes received obscene phone calls at the telephone at her console, from men who felt a woman should not have such a senior position, and she had to run to another building if she needed the bathroom — there was no ladies’ toilet where she worked.

Many in NASA felt that a woman should not be seen during the media focus on Apollo 11, the culmination of so many years of dedication, inspiration and tragedy. The debate was finally settled by the Kennedy Space Center’s director, Kurt Debus. Luckily, JoAnn Morgan only found out that others were resentful of the place she had earned in the media spotlight after the mission was over.

But when you watch the footage of that day, look out for her: one woman among nearly 500 men. A single woman who represents the contributions of so many.