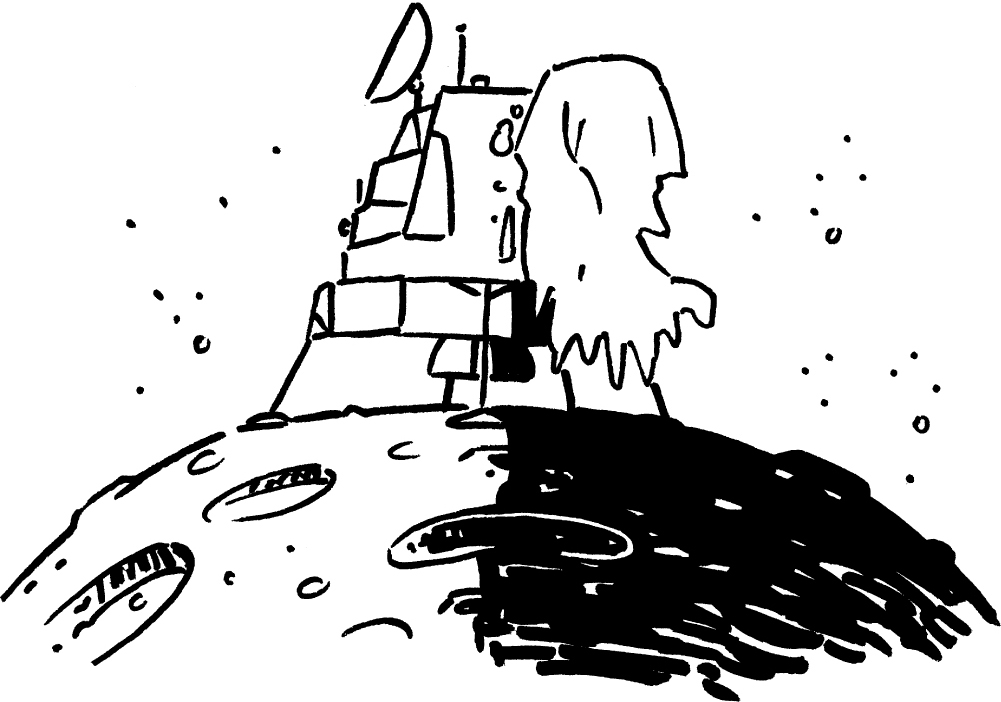

It was a land of rocks and shadows against a black starlit horizon. Close by were boulders and ridges, perhaps ten metres high, surrounded by pockmarked craters and pebbles.

Before Armstrong and Aldrin could venture out they had to check the spacecraft and the navigation computer. They had only 12 minutes to decide whether it was safe to stay — if they waited any longer Michael Collins would be out of range and they’d have to wait for him to orbit the Moon again.

Thankfully all was as it should be. The plan now was for Armstrong and Aldrin to have something to eat and rest for five hours before getting ready to go outside. The Goldstone Tracking Station, with Madrid as backup, would be the ‘prime station’ to cover Man’s first moon walk, not Honeysuckle Creek.

At least, that was how it was supposed to go . . .

THE LONG DAYS AND NIGHTS ON THE MOON

Every ‘Moon day’ lasts for two Earth weeks, and so does every ‘Moon night’. The Eagle had to land during the Moon day of course, so that the astronauts could see around them. Moon nights are incredibly cold, with temperatures dropping to –170°C.

But it’s about 110˚C in the middle of the day on the Moon — hotter than boiling water. The best time for a Moon landing was ‘early morning’ Moon time, before it got too hot. Apollo 11 orbited the Moon in a clockwise direction, so that the Sun was behind them — otherwise the astronauts would be staring towards the Sun and would not be able to see much because of its glare.