At Honeysuckle Creek we felt as if a jolt of electricity had flashed through the entire station — but with the station readiness test still to be completed we had no time to talk about it, or to ring our families and friends.

The canteen was alerted to cater for one very early and one very late lunch sitting, and the powerhouse was requested to ensure that all diesel generators were ‘on line’.

Voice traffic with Mission Control intensified through our headsets, teleprinters chattered away nonstop, the station’s TV monitors were connected to the Apollo video-processing equipment, and the public relations officer alerted the VIPs to get up to Honeysuckle Creek fast, so that they wouldn’t miss anything. (The VIPs would not be in the operations areas — only the technicians and some other staff were allowed in there.)

At last we heard the calm voice from Goddard Operations on NET 2 say: ‘Honeysuckle, NETWORK, that completes interface testing, your site is GO! Standby for Houston.’

Houston NETWORK was also calling us, as Mike Dinn announced over the station paging: ‘All positions, Honeysuckle is at H–30 minutes.’ (The H stands for ‘horizon’.)

The Houston flight controllers wanted ‘confidence checks’ — Houston COMMTECH verified the voice circuits all the way to the Honeysuckle Creek transmitters, then TIC (Telemetry Instrumentation Coordinator) verified the formats from Honeysuckle Creek’s telemetry computer, and RTC (Real Time Command) sent bursts of digital commands through Honeysuckle Creek’s command computer.

It was now 20 minutes before moon rise at Honeysuckle Creek — at which time our antenna would receive the Eagle’s signals.

Vic Burman received the latest antenna-pointing data tape which was rushed to Paul Mullen at the antenna control console. It was now H–10 minutes as the antenna rolled across the sky and pointed down to focus on the exact spot on the eastern horizon where the Moon would rise.

Cars were not allowed to approach the tracking station — they had to stop at the main gate, about a kilometre down the road, and turn off their engines in case their electrical ignitions interfered with the highly sensitive receiving equipment.

In the control room Mike Dinn was ready with the final station status report as Houston called on NET 2: ‘Honeysuckle, NETWORK, station status?’

‘NETWORK, Honeysuckle, our status is GREEN!’ We were ready.

The minutes ticked down . . . 3 minutes . . . 2 minutes . . . 1 minute . . .

Then at 11:15 am the Moon rose behind the gum trees.

Zero!

Immediately Honeysuckle Creek’s receivers locked onto the Eagle’s signals. Alan Foster on Receiver 1 announced ‘AOS LM, two-way lock’, as the Moon crept upwards.

It was the moment we had worked towards for three years — and suddenly we had little to do. Everything happened automatically now, as Honeysuckle Creek’s data rippled through the complexity of electronic systems and all the way across the world to the console screens at Mission Control.

Up on the hill our antenna pointed straight at the rising Moon, the red lights flashing around the perimeter of the dish to tell anyone passing that the antenna was transmitting to a spacecraft. The claxon horn boomed across the bushland, warning of the high electromagnetic radiation hazard.

Inside the tracking station all was calm, as we listened to the astronauts chatting away on NET 1.

Now most of us needed to do no more than watch and listen, all except for the periodic mode switch, magnetic tape change, or a patching reconfiguration request — unless something went wrong.

Everything was functioning perfectly.

Far above us, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin started to check their life-support equipment — and our smug calmness quickly changed to confusion!

Those blasted astronauts were not doing things according to the order on the flight plan! Each life-support check needed a special configuration down on Earth. What was happening up there?

Astronaut Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin takes his first step onto the surface of the Moon.

NASA

John Saxon now says: ‘Never rely on an astronaut to follow a script! They certainly didn’t, getting ready for their first walk on the Moon. Perhaps they were as excited as we were!’

The team at Honeysuckle Creek frantically tried to keep up with what the astronauts were doing as the minutes dragged by. The life-support checks that the astronauts had to do before going out should have taken two hours. Today they were taking three and a half hours! But with every second that passed our excitement grew. Until they had completed their checks and got into their spacesuits we didn’t know how to configure our station equipment to follow their signals. And we couldn’t interrupt them to ask what they were doing or it could have slowed them down.

Finally the checks were completed. We listened as the astronauts began to struggle into their spacesuits and life-support backpacks. The TV screens were still blank — there could be no visual picture until Neil Armstrong switched on the camera mounted outside the landing craft when he came out of the hatch.

It was now 12:30 pm.You could feel the excitement in the air. People began to file into the operations area — administration managers, secretaries, storemen, clerks and maintenance men. When I looked around they were all standing silently behind me. Even the station’s gardener had abandoned his ride-on mower!

However everyone stood well back, as we scanned our rows and rows of blinking lights, dials, green oscilloscopes and chart recorders, while keeping a watchful eye on the flickering TV monitors, waiting for the first sign of a picture from the Moon. Meanwhile, far away in Parkes, the big 64-metre dish of the Parkes radio telescope was heeled hard over on its edge pointing at the eastern sky — but the Moon had not risen high enough and was still just outside their dish’s field of view.

Honeysuckle Creek transmitted the final essential information to Mission Control — biomedical data, to check that the astronauts were still strong and healthy, and to check the suit pressure, carbon dioxide pressure, battery voltage and current, oxygen tank pressure, and water-cooling temperatures of their spacesuits.

At mission time 109:15:45 GET, we heard Buzz Aldrin say to Neil Armstrong, ‘Okay. About ready to go down and get some moon rock?’ He handed Neil Armstrong a bag of rubbish to leave on the Moon — this would lighten the load, saving on fuel for the return journey to the command module.

The hatch opened, and Neil Armstrong crawled out on his hands and knees, feet first, onto the platform. It was 109:24:19 GET. As Mike Linney in our telemetry area watched the biomedical data coming in, he could see Armstrong’s heart rate racing at 112 beats per minute (it was normally in the 60s).

Neil Armstrong climbed down onto the top rung of the ladder and released the black-and-white TV camera shutter.

Suddenly the flickering greyness on the TV monitors at Honeysuckle Creek gave way to a fuzzy black-and-white scene of a ladder and handrail — upside down! A few seconds later ‘Video Von’ (Ed von Renouard), the technician who operated the Honeysuckle Creek video-scan converter, realised what had happened and flicked the switch to put the picture right-way up.

Ed remembers: ‘I was 37 years old when Neil Armstrong walked on the Moon. The memory that remains with me above all others will always be that moment when the image of that glistening man-made ladder on Earth’s Moon against the black sky of the universe flicked into being on the monitor of my television processor.

‘From here this picture (as I thought of it as “my picture”) was radioed to Sydney, and from there via satellite to America and then on to the rest of the world, watching at home or on giant screens in New York, London or Moscow, a human being’s first steps onto the Moon. And I was part of that enormous undertaking involving tens of thousands of people working in America and here in Australia to make it come true. And then Neil Armstrong’s shadowy leg came down the ladder on the monitor and it was true!’

Goldstone Tracking Station in California was also receiving the TV signal, but their picture was too fuzzy to make out. Houston immediately switched over to Honeysuckle Creek’s picture.

Neil Armstrong climbed slowly down the ladder and said: ‘I’m at the foot of the ladder. The lunar lander’s footpads are only depressed in the surface about one or two inches, although the surface appears to be very, very fine grained, as you get close to it. It’s almost like a powder.’

Then he stopped at the last rung of the ladder, stretched and placed his feet onto the top of the footpad, and finally stepped off the ladder into the dust.

He stood there for a moment, testing the soil with the tip of his boot.

He said: ‘That’s one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind.’

Yes, the world watched that day. But at the tracking stations, we saw more than this historic step onto the lunar surface. We also saw Neil Armstrong’s biometrics. We watched his heart rate race as he began to open the door. We saw him deliberately calm himself as he stepped down, down, down onto the Moon. Then he realised he had got there safely — and his heart rate went wild!

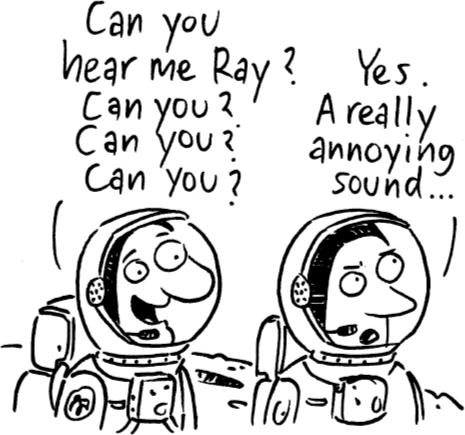

Sound is transmitted through a medium, like air or water. It can’t travel through a vacuum. There is not enough atmosphere on the Moon, so even if you yell no-one can hear you — unless you have a device like a two-way radio.

Each astronaut had a microphone inside his helmet and a two-way radio in his life-support backpack. When one of them spoke it was transmitted back to the lunar lander which retransmitted it to the other astronaut as well as to Mission Control through the tracking stations. Everybody could hear what the astronauts were saying to each other and Houston could talk to them as well.