Now we watched the man on the Moon. Neil Armstrong bounced up and down a little, and then released his hold on the strut of the landing craft. Around him the Moon shone black and silver-grey, lit by the low-hanging Sun.

Armstrong spoke again: ‘Yes, the surface is fine and powdery. I can kick it up loosely with my toe. It does adhere in fine layers, like powdered charcoal, to the soles and sides of my boots. I only go in a small fraction of an inch, maybe an eighth of an inch, but I can see the footprints of my boots and the treads in the fine, sandy particles.’

He began to walk, leaning forward to keep his balance.

(The Moon’s gravity is one-sixth as strong as Earth’s, so Armstrong only weighed a sixth of what he did on Earth. His backpack weighed as much as he did and, in the strange new gravity — despite all his training in low G on Earth — it took a few minutes to work out how to walk comfortably.)

It was a shock to walk beyond the shadow of the landing craft — it had been easy to see while he was in the shade, but the glare of full, unfiltered sunlight on the Moon took Armstrong by surprise.

He scooped up the first heap of moon rock and soil and placed it in a Teflon bag — he wanted to do this as soon as possible so that he would have a sample if the moon walk had to end suddenly. Down on Earth the TV signal from the antenna on the Parkes dish eventually came on line, with a slightly better picture than the one at Honeysuckle Creek. (The Parkes antenna was more than three times as big as ours and more sensitive.)

Buzz Aldrin left the Eagle about 15 minutes later. We listened to him joke that he was making very sure not to lock themselves out of the landing craft.

‘Beautiful view!’ he said, his voice crackling through our headsets.

‘Isn’t that something?’ agreed Armstrong. ‘Magnificent sight out here.’

‘Magnificent desolation,’ said Aldrin.

Aldrin was also shocked when he moved out beyond the shadow of the landing craft, not just by the sudden harsh glare but also by the heat. Everything looked subtly wrong to him. He then realised what it was — on Earth the horizon appears flat, but because flat, but because the Moon is so much smaller than Earth the Moon’s horizon was curved, sloping down away from him. And everything was so clear and bright without the filtering of Earth’s atmosphere.

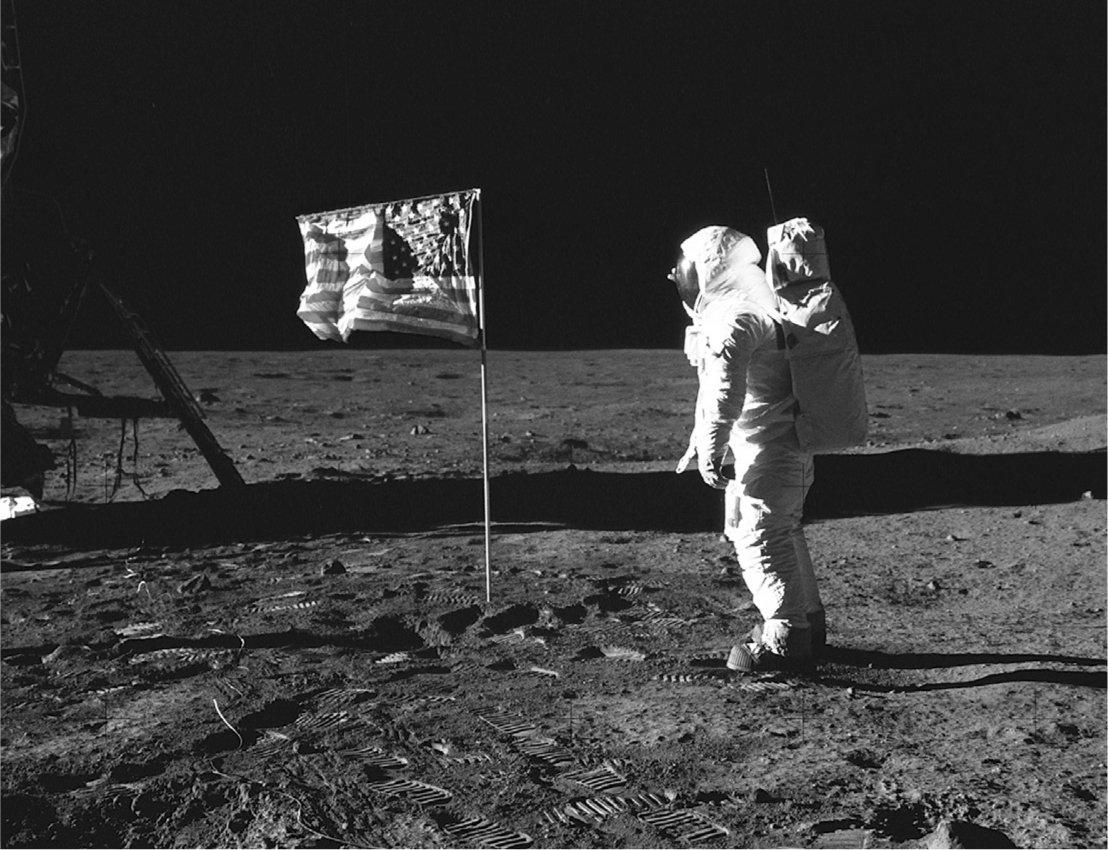

Neil Armstrong took this photo of Buzz Aldrin beside the deployed United States flag. The Eagle is on the left, and the footprints of the astronauts are clearly visible in the soil of the Moon.

NASA

The two astronauts set up the TV camera on a tripod about 50 metres away so that the world could have a better view of the landing craft and the astronauts; they collected more samples and checked the outside of the craft. Later, Armstrong would say it felt as though they were in a land beyond time. On Earth the world around you changes day by day. But on the Moon nothing changes at all, unless it is hit by a meteorite.

The giant ball of Earth hung in the sky above them, all blue and swirling white, half in darkness and half in light. It shocked Buzz Aldrin when he realised that the soil he was standing on was older than any from Earth — where the soil was continuously lost to wind and rain, formed by volcanoes, rising or sinking as continents grind together or shift apart. Here nothing moved at all.

They placed the United States flag in the Moon’s soil. President Nixon was watching the moon walk from the Oval Office in the White House. (And in the graveyard at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia someone placed a bunch of flowers on President Kennedy’s grave with a note that said: Mr President, the Eagle has landed. President Kennedy had been assassinated before he could see a man on the Moon — but his promise to the world had been kept.)

A special phone had been connected in the Oval Office for President Nixon to speak to the astronauts on the Moon. The world watched as President Nixon spoke:

‘Because of what you have done the heavens have become part of man’s world. And as you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility, it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to Earth. For one priceless moment, in the whole history of man, all the people on this Earth are truly one. One in their pride in what you have done. One in our prayers that you will return safely to Earth.’

Did President Nixon mean what he said? Or was it just a speechwriter’s fancy? The United States was still in the middle of the Cold War, and becoming more deeply embroiled in the Vietnam War. But even if they were just words meant to sound good, others who heard them gave them substance.

WHAT ARE THE STRANGE LIGHTS ON THE MOON?

For the past few centuries, observers squinting through telescopes at the Moon’s surface have seen dancing lights, coloured glows and mists that last anything from a few seconds to an hour or two. Even the Apollo astronauts saw the Moon’s surface shining with an eerie light.

What are these lights? Perhaps they don’t come from the Moon at all. Here are some thoughts of what they might be:

• Light shining on dust in Earth’s atmosphere or reflected earthlight shimmering through our atmosphere.

• Flashes caused by pockets of gas or vapour trapped just below the lunar surface, which are released by a meteorite strike or a moonquake. Apollo 15, flying low over the crater Aristarchus, found evidence of a faint vapour from the crater.

• Although the dust Neil Armstrong kicked up looked like it had been undisturbed for millions of years, and there has never been any sign of lava flows or volcanoes (the last volcanic activity on the Moon seems to have occurred two to three billion years ago), it could be that the core of the Moon is still partially molten — as Earth’s is. Gas escapes through weaknesses in the Moon’s crust.

• When the walls of craters crumble they release trapped gas.

• The sunlight causes short-range electrical fields by ionising atoms on the surface of sunlit rocks, and these electrical fields raise dust grains a few metres off the surface of the Moon.

P.S. There are no giant volcanoes on the Moon. However there do seem to be vast underground tunnels, possibly formed either by long-ago volcanic action or meteor strikes. The craters themselves were all formed by meteor strikes.