The Apollo missions continued, each becoming more challenging and more technically complex for the tracking stations. Greater amounts of information were crammed into the downlink signals; the tracking ability had to be increased. Computers were upgraded, video processing went to full colour and the number of individual downlink signals increased.

Neil Sandford at Honeysuckle Creek also designed and supervised the building of a large simulation console — a giant desk able to generate signals as though they were coming from a spacecraft — for us to practise on. NASA was incredibly impressed with this, and if the Apollo programs had continued a simulation console would have probably been installed at every tracking station.

More and more science experiments were conducted on the Moon — the Apollo 14 (January 1971) astronauts used a small-wheeled trolley to carry their tools and cameras which enabled them to explore and collect rock samples several kilometres from the lunar landing craft.

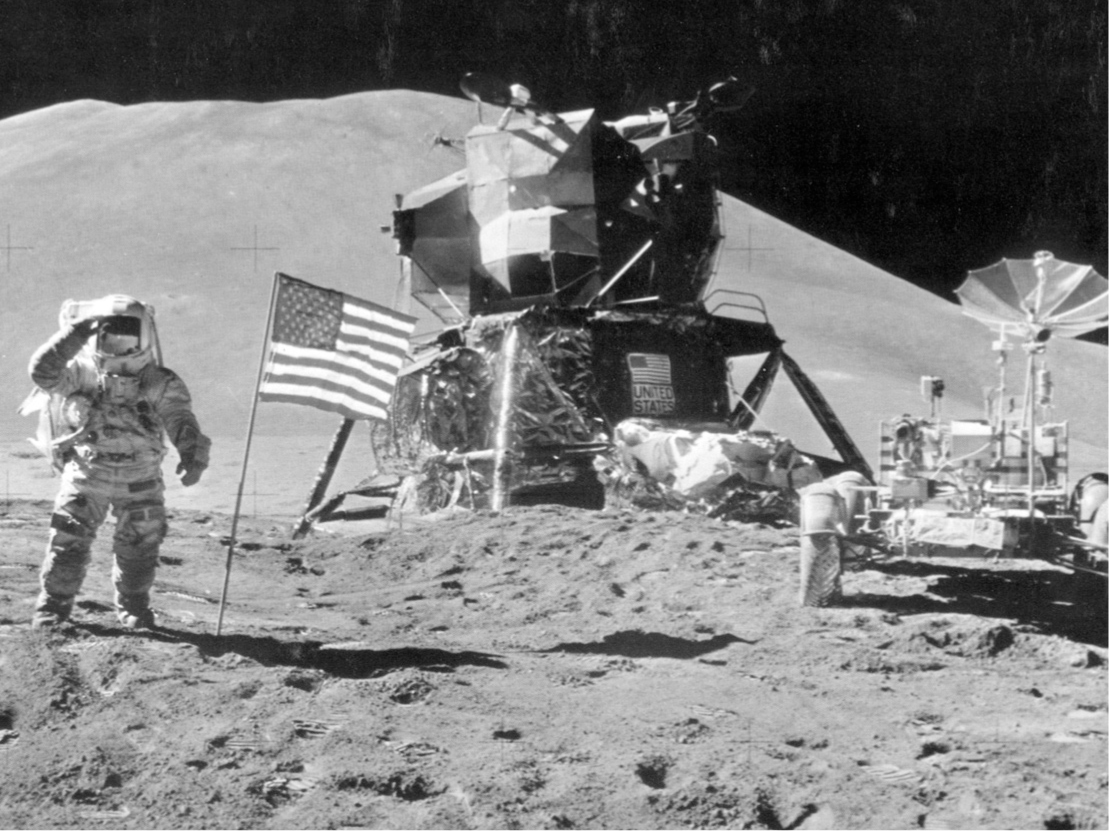

Apollo 15 astronaut Irwin salutes flag. Lunar rover vehicle accompanied this mission.

NASA

The Apollo 15 (July/August 1971) astronauts launched a small satellite into lunar orbit to measure charged electric particles. This needed separate tracking, as did each new ALSEP scientific experiment package.

Apollo 15, and later Apollo 16 (April 1972) and Apollo 17 (December 1972), also carried a lunar rover vehicle so that they could explore more areas of the Moon. These moon buggies needed precise tracking as they moved a long way from the lunar landing craft. The Honeysuckle Creek antenna had a tracking accuracy of one-thousandth of a degree, a beam width of half a degree and could measure range at lunar distance to an accuracy of 15 metres.

And finally Apollo 17 took the first astronaut scientist, Harrison Schmitt, a geologist, to the Moon.

But by now, space budgets were being slashed in Washington DC. The public, divided over the Vietnam War, had turned its attention to more earthly concerns — the war, poverty, racial inequality and the threatened environment. How could anyone talk of sending human beings to Mars, asked politicians, when there were people starving on Earth?

By the time Apollo 15 was launched, NASA had already cancelled the last three Apollo missions (Apollo 18, 19 and 20) to save funds.

Despite these events Honeysuckle Creek was still an exciting place to work. Hamish Lindsay remembers one of the best moments of Apollo 15: ‘During the Apollo 15 mission I went out to get some fresh air after dinner. I walked outside to the grassy slope beside the antenna and joined a group of kangaroos feeding on the lush green grass. They took no notice of me, just kept on chewing at the grass. Apart from the whine of the servos driving the antenna it was the quiet of evening.

‘I looked up at the Moon, shining brightly in the dark blue sky behind the antenna. The sun had set, but its afterglow was still brightening the western horizon. Then I looked through the window at the television monitor and could see the astronauts Scott and Irwin walking around the Moon’s surface and I thought how lucky I was. Here I was in the Australian bush with kangaroos cropping the grass beside me, up there I could see the Moon, and turning a bit to my right could see the astronauts bouncing around the lunar surface.’

Brian Hale remembers: ‘I went to work at Honeysuckle Creek in 1972. Within four weeks I was dumbfounded watching astronauts driving around the Moon in the lunar rover vehicle. This was great, and they were paying me to do this! About $90 a week I think.’ (However as Martin Geasley says: ‘We had such great pride in what we did — I guess most of us would have worked for nothing more than the privilege of being one of the team.’)

By the time of the Apollo 16 mission John Saxon and I were joint operations controllers, working opposite 12-hour shifts. We coordinated all the data flowing through the station from the two giant antennas through to the computer systems and out of the station via the communication lines ‘patched’ direct to Mission Control.

John and I had to maintain relentless concentration, monitoring many voice conversations all happening at once in our headsets, while keeping our eyes on multicoloured status lights and reading high-speed printouts.

Keeping track of the mission flight plan, anticipating events, being aware of the station’s configuration and status at all times and being ready to execute any contingency procedure, was exactly what John and I had trained for.

During the Apollo 16 mission we lost communication with Houston. John Saxon had seconds to decide what to do. Suddenly an Aussie voice crackled up to the spacecraft:

‘Orion, this is Honeysuckle. We have a COMM- OUT with Houston at this time. Standby one please.’

There was no need to say any more, but the astronauts enjoyed the novelty and kept on chatting. It was the first time they had talked to anyone except the CAPCOM at Houston!

‘Okay Honeysuckle. Nice to talk to you. How’re you all doin’ down there?’ asked Charlie Duke.

‘We’re doing great. Nice to talk to you,’ replied John. Astronaut John Young mentioned later how much they’d all like to ‘come down there and see you folks!’. ‘You’ve got a permanent invite!’ said John Saxon. ‘We’ll keep the beer cool for you!’

‘Honeysuckle,’ drawled John Young in his American accent, ‘you’ve got a couple of fellows just going to show up on your lawn.’

It took 23 years for John Young to show up. He came out to Australia for our Apollo 11 reunion in Canberra in 1994. It was an emotional reunion for us all.

As John Saxon said later, that 12-year-old kid building a radio in his bedroom had never dreamt that one day he would talk with astronauts in space. Actually John would rather have been up in space himself — but as John says, being there in your imagination is almost as good.

For me, Apollo 16 is unforgettable — the excitement, the camaraderie, but most of all the extraordinary energy of being part of the team, all proud of their role and completely focused on their own contribution to the performance of the station and the success of the mission.

Sometimes in the afternoons here in our valley I relax with a glass of milk and a chocolate while I look back through my entries in the station operations console log book. These days I have to struggle to remember what all the long-ago abbreviations and space jargon meant.

Apollo 17 was the final manned mission to the Moon. As each significant event in the flight plan was ticked off everyone at Honeysuckle Creek knew that this was the last time we would perform these operations. But we had no time for sadness — there was still too much to do.

When the lunar module blasted off from the Moon’s surface and left the descent stage of the lunar module standing on its legs in the loneliness of the Taurus-Littrow Valley, we knew that we would receive no more data from those discarded life-support backpacks or from the lunar rover vehicle, abandoned nearby.

And, finally, when the astronauts were all together in the orbiting command module and the lunar module ascent vehicle was jettisoned away to crash on the Moon, the lunar module team of flight controllers in Houston packed up their briefcases, collected their belongings and filed out of the Mission Control room for the very last time, marking December 1972, as the end of manned exploration of the Moon.

As our adrenalin wound down, we had time to realise that an era had come to an end.

NASA would now focus on a new mission, to reduce the cost of access to space with the reusable space shuttle.

CAN THE MOON TELL US HOW EARTH AND OTHER PLANETS BEGAN?

Perhaps. Asteroids and meteors that fall to Earth are quickly destroyed by Earth’s weather — not to mention by grass, bacteria, the odd earthquake or volcano etc.

However rock from meteor impacts from the ancient giant meteor clouds of Mars, Venus and ancient Earth might have landed on the Moon. (We know that rock blasted from Mars by meteors has landed on Earth. The 15-centimetre long Martian meteorite ALH 84001 was found in Antarctica in 1984 and some scientists believe that it shows evidence of ancient Martian microbes.) On the Moon the ancient meteors would still be intact.

The early history of the solar system could be preserved on the Moon — and nowhere else. Up to 20 tonnes of Earth rock may be scattered across every 100 square kilometres of the Moon’s surface, along with about 180 kilograms of rock from Mars, and between one and 30 kilograms of rock from Venus.

Not much rock would have come from Venus because it is so close to the Sun that the Sun’s gravity would pull most of the debris towards it. However an asteroid 10 to 200 kilometres wide hitting the planet would punch a hole in the atmosphere through which up to 10 per cent of the asteroid’s mass could escape as outbound meteors.

No-one has found a meteorite from Venus yet. It would be easy to spot as it would have much lower levels of argon. Moon rocks and Earth rocks are much more alike, but rocks from Earth contain tiny traces of water that can be found with infrared scanners.