I saw my first computer — or ‘electronic brain’ as they were called then — in 1958 at the head office of the IBM Corporation in William Street, Sydney. It was one of the first computers in Australia, and nothing like the computers we know today — it occupied an entire room. The rows of electronic racks and magnetic-tape machines were fragile, and very sensitive to dirt and dust — these early computers had to live in a special room with filtered air and controlled temperature and humidity.

I was fascinated. Space was beginning to fascinate me too.

In 1962 John Glenn became the first American astronaut to orbit Earth for Project Mercury. Afterwards, Glenn’s fragile-looking little spacecraft, Friendship 7, was brought out to Australia.

I stood in the long queue in Sydney’s Hyde Park one summer evening, and marvelled at the tiny little red vinyl-covered seat in front of the control panel, which was a bit like the dashboard of a very small car. The simple clocks, dials, gauges and shiny toggle switches looked like they’d been made in a backyard shed.

Many people had come to marvel at what had been done by one brave man in this tiny tin can of a vehicle. But I wanted to know what was behind that little control panel — the state-of-the-art navigation, flight control and communication systems!

What powered the engine? What guided it in space? What sort of radio gear did it have? How was the flow of the oxygen controlled? Did it have any batteries?

If only there was a workshop or owner’s manual to study. I knew then that somehow, some day, I would have to find a way to work with spacecraft and guided missiles.

The first step was to learn about computers. It would be years before the first computer courses were offered at university or technical college — and even longer before computers would be introduced into schools! The only way to learn about computers in the early 1960s was to join a computer company.

The world’s first business computer was the LEO (Lyons Electronic Office). The original British LEO 1 computer was made as an accounting machine for the Lyons Tea Shops in London. I joined LEO Computer Ltd (Aust) and worked with the LEO 3 model. Anyone who knew anything about computers in those days was called a ‘boffin’. I had at last become one of them, with my thick black-rimmed glasses and white dust coat. But by the public at large I was called a ‘computer scientist’. From there I went to work on the guidance systems for the Ikara anti-submarine missile and the Jindivik pilotless jet aircraft projects. In 1966 I saw an advertisement for staff for a NASA project at the new Honeysuckle Creek Space Tracking Station in Canberra, to help track spacecraft that would take men to the Moon.

This was it!

HOW THE JOURNEYS TO THE MOON CREATED THE INTERNET

Today we take it for granted that our computers can talk to each other — you can email a friend in China or the United States and they will receive your message in an instant.

Before the space programs began each computer was an entity of its own — they were room-sized monsters that needed their own air-conditioning systems, even their own special power supply, and they were tended by lots of people in white dust coats.

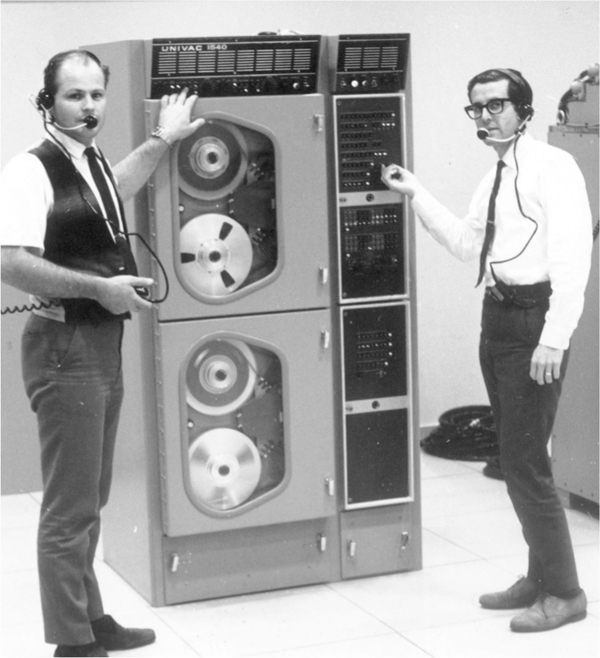

The tiny computers carried on the Apollo spacecraft were several thousand times less powerful than one of today’s home PCs. Even the large cumbersome computers at Honeysuckle Creek — each as big as two refrigerators — were several hundred times less powerful than any of the ones at your school.

The computer in each Apollo spacecraft ‘talked’ with the worldwide ground-tracking network computers. Each NASA tracking station had three or four computer systems, which fed spacecraft engineering information into a giant IBM computer hub at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland in the United States. These IBM computers in turn communicated with the ‘real-time’ computer complex at Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas.

By the early 1970s many tracking-station technicians were making experimental ‘home computers’ — miniature versions of the bulky ones at the tracking stations. One evening I went to my mate Don Loughhead’s garage to see his experimental mini computer.

Ron Hicks (left) and Bryan Sullivan (right) beside one of the large tape machines at Honeysuckle Creek.

RON HICKS

It took up most of a long bench along the wall. I watched as Don typed characters on an old teletype keyboard. The characters passed through heaps of small home-made electronic bits and pieces, separated by jumbles of wires, like untidy coloured spaghetti, and miraculously appeared on the old mechanical printer at the other end of the bench. (In 1986 I showed my wife Jackie how to use a computer connected to a ‘ham’ radio transceiver to send keyboard text messages from my computer to my mate Dik Elliot’s computer on the other side of town. There was no such thing as email in those days and no-one had heard of the internet — but this was part of its beginning. Jackie had great fun playing with it!)

At the same time Dik and I had astonished the Wireless Institute members in Canberra by sending keyboard text from my Apple Mac computer in the meeting room to another PC in the opposite corner and then out to Dik’s computer in his locked car in the carpark. The text was then retransmitted to a fourth computer back in the meeting room — all via radio links, without wires — true ‘wire-less’ communication! Apples and IBMs could talk to each other even in those early days.

Nowadays it all sounds so ho-hum, but back then it knocked the socks off all who saw it — the real leading edge of technology!

During the 1970s NASA established a worldwide network of computer communications. In the 1980s academics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) further developed these systems to enable university people to communicate rapidly with each other via their new desktop personal computers. This formed the basis for the development of email, online banking, rapid airline bookings, interactive games, as well as instant information on millions of topics. The internet was born.