Canberra, Tidbinbilla and Honeysuckle Creek

In 1966 Canberra was just a big country town, with sheep grazing on its outskirts. And everyone in the area knew everyone else. My first wife, Anne, and I and our baby daughter, Elizabeth, settled in a new house in the southern suburb of Curtin. Public servants, newly arrived to Canberra, lived in every other house in the street, and all of them had young children, too.

Because the Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station was still being built, all of us early arrivals began work at nearby Tidbinbilla Deep Space Tracking Station just outside Canberra. Our job was to help track the Surveyor spacecraft. For the first time, NASA would use a spacecraft to try to land a package of scientific instruments on the Moon.

Tidbinbilla was a shock adjustment for me after working in industrial Sydney. The tracking station was surrounded by grassed hills and paddocks, with kangaroos resting in the shade of the antenna during the day.

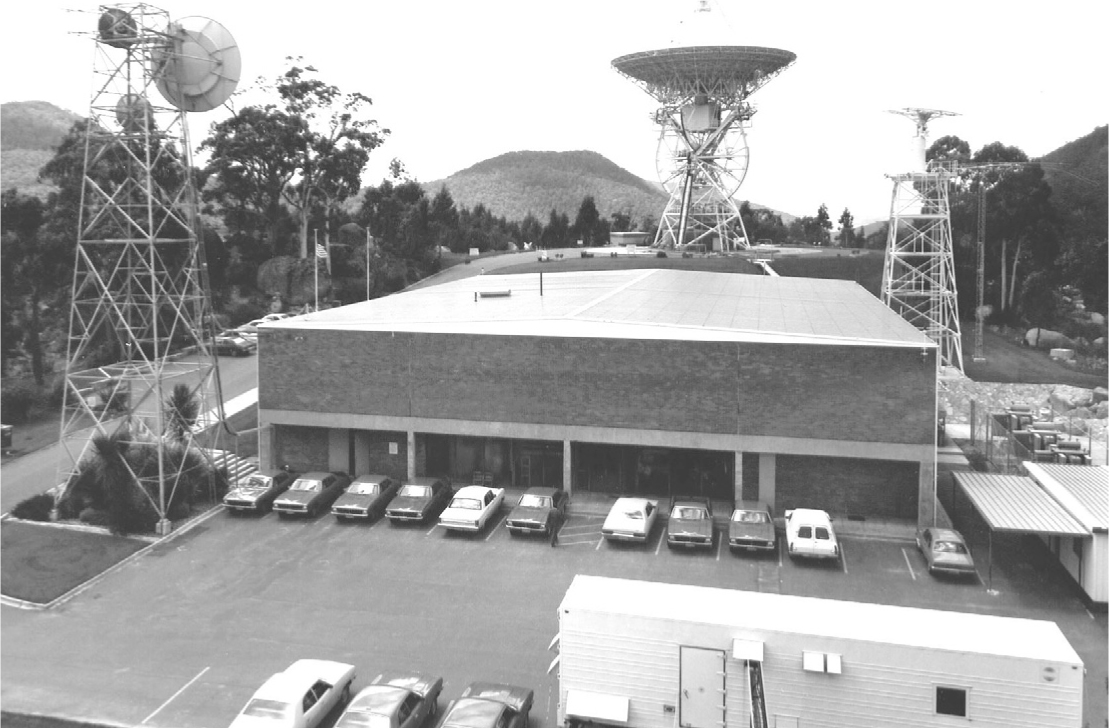

Tidbinbilla station during the Apollo days when it had two antennas.

HAMISH LINDSAY

All NASA space-tracking stations were located in remote areas to reduce electrical interference from traffic, radio and television signals and industrial machinery. Because signals from distant spacecraft were usually weak, the antenna-receiving equipment had to be extremely sensitive — any type of electrical interference would disrupt the signals.

Tidbinbilla was like a dream come true. Dozens of operators sitting in large padded chairs, each wearing a headset and microphone, occupied the thickly carpeted operations room. There was electronic equipment everywhere! Rows of racks ran the length of the vast operations room, each crammed with switches, knobs, dials, meters, coloured lights, displays and oscilloscopes. (An oscilloscope is a measuring device — you plug its leads into the wiring of whatever apparatus you want to test, and its screen shows green wavy lines which tell you what’s happening within the electronic circuitry of the item you are testing.)

The station director sat at an enormous control desk in the centre of the room with a commanding view of the whole operations area. Through plate-glass window I could see the movement of the huge 26-metre dish antenna, as it pointed directly at the distant spacecraft it was tracking.

I was assigned to help out in the computer section. There was an enormous amount of information to absorb and learn — every aspect of aerospace technology from tracking, engineering and operations, even the design specifications of the spacecraft itself.

This was better than anything I had ever dreamt of.

Our computers processed all the data that came from the spacecraft as well as all the commands needed to keep it flying. Once the Surveyor spacecraft was boosted from Earth’s orbit and separated from the final stage of the launch rocket, the flight controllers had to calculate exactly where it was as it sped along its flight path to the Moon.

There are no road maps in space! The spacecraft’s optical sensors worked out where Canopus, a bright star in the southern sky, was in the blackness of space. The onboard spacecraft’s computers, programmed to make the spacecraft move, pointed it in the right direction by firing its tiny thruster rockets. The spacecraft then slowly rolled itself around until the side with the optical sensor detected the brightest object in its field of view, the Sun. It would then stop the roll using its attitude thrusters. This operation was called the ‘attitude manoeuvre’.

All our tracking data was sent to Mission Control at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California via computers at Tidbinbilla at a high-speed data rate of 1.2 kB/sec. Your home computer sends messages about 100,000 times faster, as does your smartphone, but at the time it was an extraordinary speed — the most modern, state-of-the-art, American technology, with apparently no expense spared. For a guy like me it was a magic opportunity.

Meanwhile the Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station building where we were going to work was being finished. The construction was a massive task, not only because of the size of the place but also because of its remote location. The site was chosen for several reasons. Its isolated location — surrounded by granite peaks in the Australian Alps — shielded the station from man-made radio noise. It was also close enough to Canberra for staff to commute.

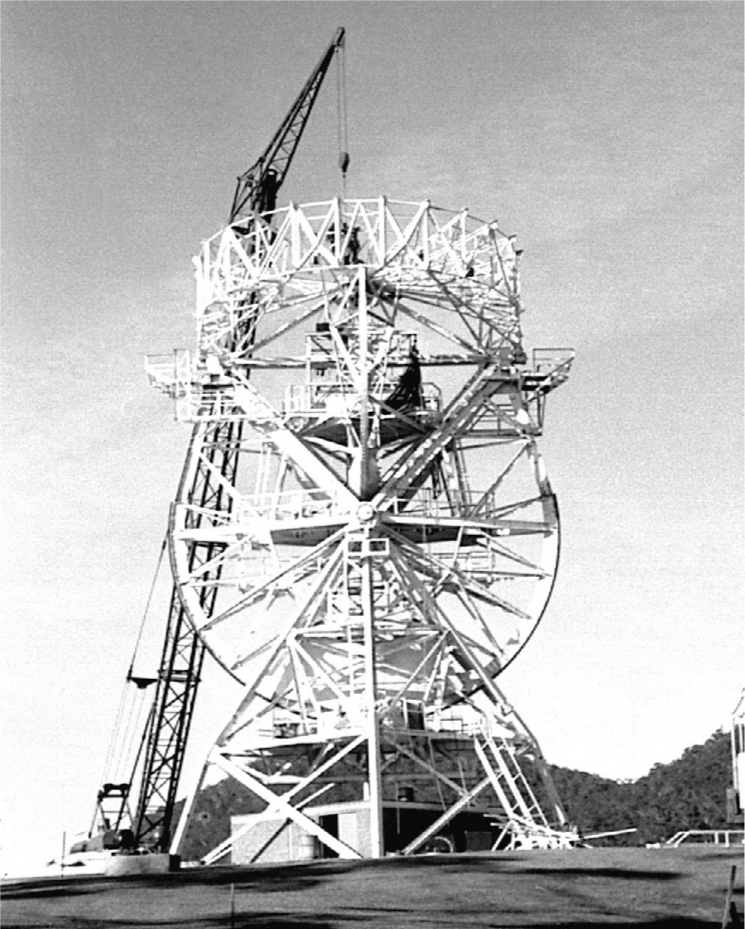

An overall view of Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station from the west.

HAMISH LINDSAY

Honeysuckle Creek was certainly one of the most peaceful settings for any NASA tracking station, but you did take your life in your own hands to travel up there. For the first two years the only track up to the station was a four-wheel-drive bush track through boggy paddocks and along steep hillsides — dangerous after snow or rain, and sometimes impassable.

The workmen arrived in an old battered Bedford bus — until one day its brakes failed and it went over the edge, fortunately without loss of life. (The old bus is still rusting in its hidden grave there today.)

Charging through mud and slush in a four-wheel drive just added to the excitement of those early days. Even the giant antenna was transported to the station in pieces, like an enormous metal Lego set. It took a year to erect and test it.

A temporary telephone and data cable to the Honeysuckle Creek site had been put in by the Postmaster-General’s Department — just a thick, black cable, strung on small, white porcelain insulators attached to the trunks of gum trees beside the mountain track.

After NASA’s Director for Manned Space Flight visited the site, NASA quickly paid for a new, sealed mountain road and proper underground communication cables.

The 26-metre antenna under construction.

HAMISH LINDSAY

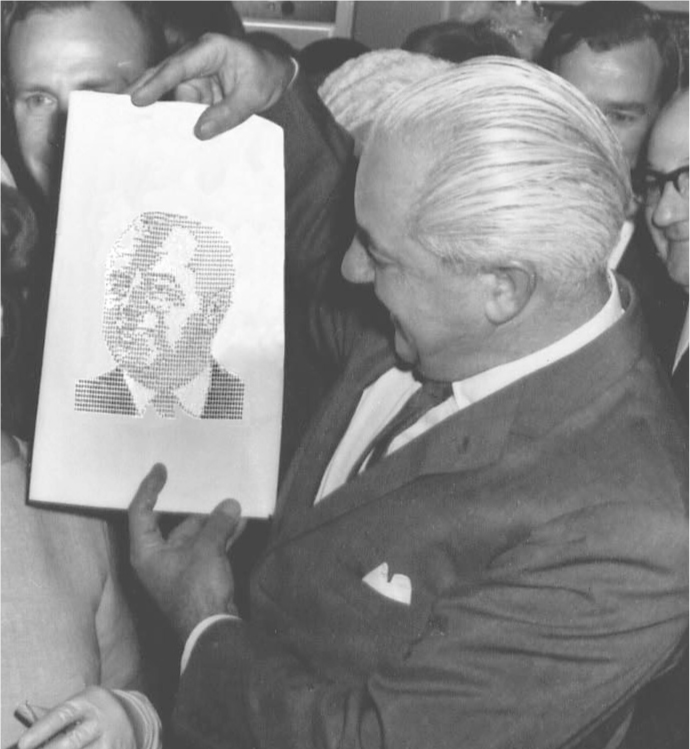

Finally the building that had started to be built in February 1965, was completed in December 1966. The station was opened on 17 March 1967, by Prime Minister Harold Holt. Several hundred people, including all our relatives and friends, attended the official opening ceremony, which was followed by a lunch under a big, striped marquee, and a tour of the station. It was an afternoon of extraordinary pride for us all, showing off our station’s equipment and explaining the role we were going to play in the Apollo missions.

To celebrate the occasion Ron Hicks and I programmed one of the computers to print an image of Harold Holt’s face. We selected combinations of alphabet characters to form light and dark shades of physical features. Nowadays we can print out high-resolution digital photographs, but in those days it was a clever trick. The Prime Minister stared at the computer image in amazement — and the next day the front page of the Canberra Times featured the photo of the delighted Prime Minister with Ron and me.

Prime Minister Harold Holt holding up a portrait of himself produced from the station computer on the official opening day, 17 March 1967.

NEWS LTD

It was fun to show off the high-tech wizardry of the station to visitors. But it was now time to get down to the real work.

The moons of other planets have names, like Callisto or Europa. But our Moon is just the Moon. It’s a bit like calling your dog, ‘Dog’.

Should we give our moon a name?

Our planet has the name Earth.

If the Moon should have a name, what should it be called? ‘Diana’ or ‘Selene’, after the ancient moon goddess? ‘Luna’? ‘Apollo’? ‘McTavish’, because it’s a really cool name? Or ‘Hey, you in the sky?’

P.S. I vote for ‘Selene’ or ‘Luna’.

WHY CAN WE SOMETIMES SEE THE MOON DURING THE DAY?

The sunlight is so bright that we can’t always see the reflected light from the Moon. Occasionally, however, the conditions are right and we can see the Moon faintly in the daytime. In fact the Moon can be seen easily in the daytime provided that it is in more than its thin crescent phase — it’s just that most people never look for it.