We were working in a high-tech world among gum trees and kangaroos, high in the hills an hour’s drive outside Canberra. Snow drifted onto our antenna dish in winter and made the roads black with icy sludge. In summer the air shimmered with eucalyptus oil, and at night the Moon rose behind the nearby mountains.

We travelled to and from the station in staff cars, usually in a convoy of six or seven cars, with four people to each car. The cars travelled along the lonely country roads — often at very high speeds. There were lots of minor accidents (including the time we hit a cow). Local farmers soon got to know our shift changeover times and made sure that they (and their cows) stayed off the roads!

On one particularly cold and frosty morning, our car approached the small single-lane wooden bridge across the Murrumbidgee river. Slowing down rapidly to avoid skidding on the ice-covered timbers, we were confronted by a large brown cow standing on the bridge facing us. The immediate problem was how to encourage this sizeable animal to move back and let us through. It soon became obvious that this was not going to happen. Our driver, Laurie Turner, thought that if we proceeded very slowly towards it, the noise of the engine would make it turn around and wander off the bridge. This strategy failed. Laurie inched closer and closer until we had a stand-off, bonnet to big nose, but still no movement. Laurie gently tooted the car horn. Instantly, this big cow flicked its head sideways and put one of its short horns straight through the driver’s side mudguard, leaving a neat one-inch hole through the metal body. All the passengers assured the Admin Manager that they were asleep or dozing, and hadn’t noticed anything. Laurie was ‘punished’ by having to fill out the insurance paperwork.

Often, the cars got bogged or slid off the steep mountain tracks into a ditch in the snow and slush, and once a large section of the mountain road collapsed in a slide of mud and rubble. Many times I’d return home with snow still on the bonnet of the car.

Our first few months working at the station were spent unpacking and assembling the technical equipment as it arrived on site. Every week a truckload of boxes and racks of equipment arrived from the United States via the Australian Department of Supply. It was a bit like having Christmas every week — each piece of equipment was eagerly unpacked. The rest of the week was spent assembling the parts. Hundreds of cables also had to be labelled and laid out under the false floor of the operations room.

Nearly all of us at Honeysuckle Creek were young. Some came from other NASA tracking stations at Carnarvon in Western Australia, Woomera in South Australia, and Cooby Creek in Queensland. Those who worked at Honeysuckle Creek were from a variety of professional backgrounds: the army, air force and navy, civil aviation, television, computing and local electronics industries.

There was one guy, Martin Geasley, who had been Senior Technical Officer Team Leader at Shannon Airport in Ireland. He jumped at the chance to be involved in space tracking when NASA advertised in the British press for personnel to go to Australia for the Apollo program.

Some new staff were assigned to the station immediately, while others were sent straight to the United States for specialised training. Throughout 1967 new staff appeared each week and those returning from training had to give the rest of the crew courses in what they had learnt.

As technical staff, each of us had to know as much as possible about every aspect of space-tracking operations. In the United States’ tracking stations there were enough staff for every member to be able to specialise. But in Australia we all had to be familiar with as much equipment as possible and to be able to do other jobs in an emergency — our roles were much more multi-skilled.

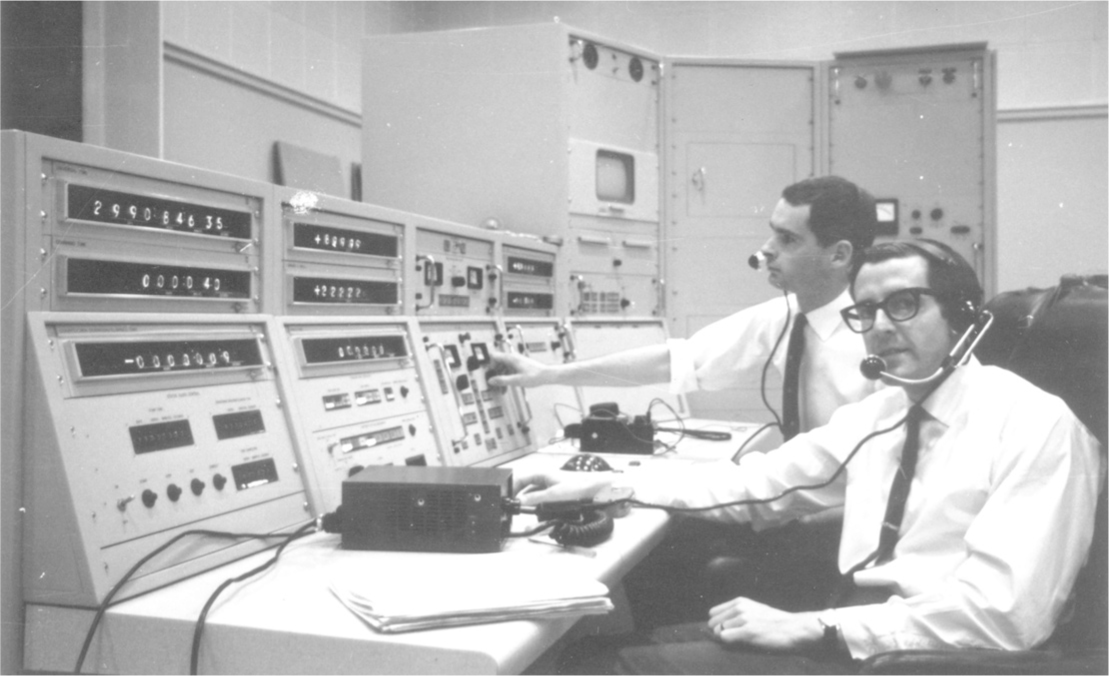

Bryan Sullivan (front) and Gordon Bendall sitting at the antenna control console. The digital displays show the exact angles between the antenna and the distant spacecraft.

RON HICKS

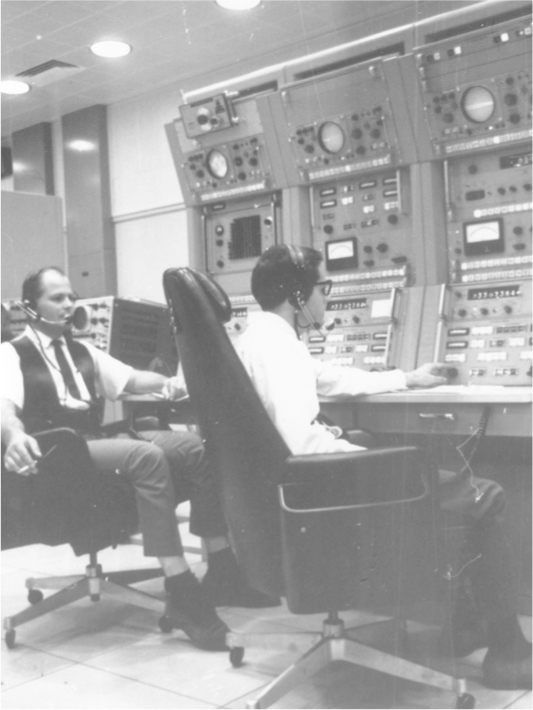

Bryan and Ron Hicks checking spacecraft commands transmitted to Honeysuckle Creek via teletype-punched paper tape.

THE CANBERRA TIMES

Bryan and Ron at the receiver control panels, where the signals from the spacecraft are tuned and locked so that the antenna can track them automatically.

HAMISH LINDSAY

NASA regularly sent ‘mission specialists’ to oversee certain operations at each of their tracking stations. Generally, the knowledge of each specialist was limited to one specific area or piece of equipment.

It soon became obvious to us Aussie technicians that knowledge equals power — in the American system, very few people had a wide view of everything. The Americans were paid well to work intensively on a very small task. We were expected to understand the broader picture — and most of us were either electronic enthusiasts or amateur astronomers.

Honeysuckle Creek was a demanding, yet fascinating, place to work. It was literally the centre of our lives. Normal working hours were between 8:00 am and 4:30 pm. However during Apollo missions everyone had to work 12-hour shifts, plus a half-hour hand-over period when the crew going off duty briefed the incoming crew on what had happened during the previous shift. Along with at least an-hour-and-a-half travelling time to and from the tracking station, that three-hour commute and our work left very little time to be with family — or even to sleep.

Eventually our new office furniture arrived to replace the makeshift chairs and the packing-crate desks. Our working area now had a more professional look as well as some home comforts. Just about every bit of space behind the racks of technical equipment was filled with filing cabinets and bookshelves for the many technical manuals.

The most impressive pieces of furniture were our operators’ chairs. They swivelled and tilted, had wheels and comfortable armrests and, best of all, high backs, all in a durable heavy black vinyl finish — just the thing for the upcoming long periods of tracking operations.

My work centred on the computer area. Our big UNIVAC military computer systems were at the heart of the tracking station. Each huge computer was housed in a giant wardrobe-sized cabinet. The information was stored on magnetic tapes which came on large dinner plate–sized spools.

The NASA computers processed everything — tracking the spacecraft, talking to other computers at tracking stations and Mission Control, and monitoring everything from the performance of the spacecraft to the astronauts’ heartbeats.

Our team soon mastered the art of programming these new computers — Ron Hicks programmed one computer to play the card game ‘Blackjack’ and Gordon Bendall created a music program. (How dull, you’re saying — everyone has computer games. But in those days few people were able to coax a computer to play games!)

The games were great fun and an excellent way to impress visitors. They also helped us get to know the hardware and software very well. If there was a computer failure, we would be able to create new testing software to solve the problem.

There was also a serious side to programming — Bill Waugh, Ron Hicks and I designed software which enabled us to read the engineering measurements from the second Surveyor spacecraft — this provided valuable training for the upcoming first Apollo mission.

As technicians we became so fond of our computers that we’d talk about them as though they were human, using statements like, ‘It thinks that . . .’ or ‘Oh, it’s confused by . . .’. In those early days of computer technology many people listening to us actually wondered if these strange new powerful machines had feelings as well as ‘intelligence’.

Our computers would seem strange to you. It wasn’t just their massive size that made them different from today’s computers. Our computers were controlled through commands, mostly in coded letters and numbers, typed in by an operator at the console. Each of us had to remember keyboard commands of vast combinations of numbers and letters as well as know exactly how a computer worked. We had to know binary and octal arithmetic notation and understand weird things like hexadecimal and baudot code systems.

I don’t think any of us would have ever believed that one day every school and most homes would have their own computers — or that my grandson could use one when he was four years old!

Throughout the operations area all the technicians and operators wore headsets with microphones attached to their consoles by long, spiral black cords. This allowed us to move about among the equipment racks while maintaining voice contact — sometimes having several conversations at once — with supervisors, flight controllers at Mission Control in the United States and other operators at the station.

It required incredible concentration. Each conversation could be vital — we also had to monitor everyone else’s conversations in case any information was missed. The long nights were the worst. This was daytime in the United States when most of the critical mission operations were carried out. Most of us relied on regular cups of strong coffee to maintain our concentration span through the night.

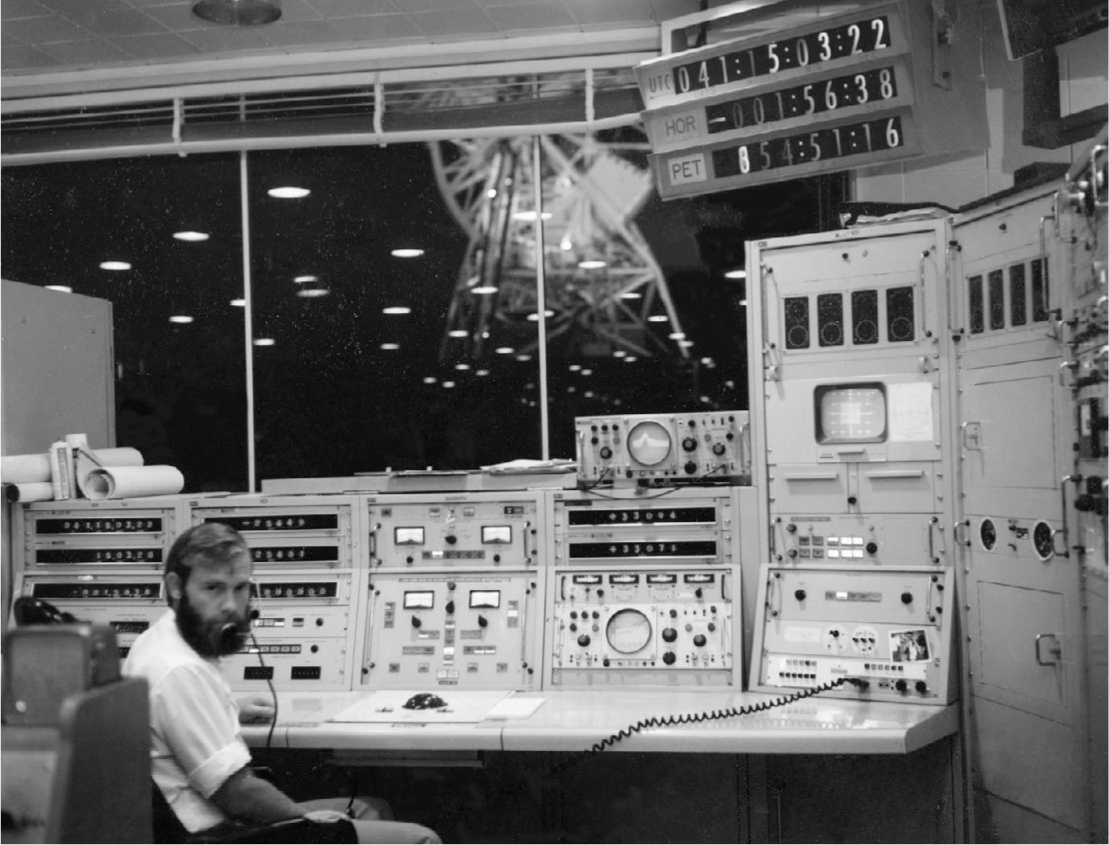

One of the weirdest sights for visitors was the giant box of digital clocks suspended from the operations room ceiling. One showed the Julian day — the ‘sequential day number’ (from 1 to 365) of the year — as well as Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) in hours, minutes and seconds. Two more rows of digits indicated the ‘elapsed time’ in hours, minutes and seconds since lift-off. Also displayed was the ‘horizon time’ which showed when the spacecraft would appear on our local horizon.

On the wall there were also a number of round clocks that appeared ordinary-looking at first glance. But they had four hands with the number ‘twelve’ where the ‘six’ should be, and a double zero at the top. They were 24-hour clocks with an extra hour hand to indicate the GMT hour.

We always found our range of clocks perfectly straightforward but most visitors were confused by them and kept looking at their own watches for reassurance.

Hamish Lindsay at the Unified S-band area that controlled the 26-metre antenna. Notice the digital clocks at top right.

HAMISH LINDSAY

I’ll never forget what it was like to come to work at night. The station had to be manned around the clock. I usually dozed as the car carried me through the tiny village of Tharwa and up the narrow mountain roads, and then woke up as the car paused at the security gate. Beyond the darkness you could see the brilliant white dish, with the roos grazing under the floodlights. Every time I walked across the carpark in the cold night air I wondered what had happened since my last shift, anxious to talk with my now weary colleagues about the current mission’s progress.

Inside the tracking station the lights were dazzling after the quiet darkness, and although there was always an incredible amount of activity, there was total concentration on the tasks at hand, with everyone high on caffeine.

First came a change-of-shift briefing in the conference room, followed by a quick read of the teletype briefing messages. Then I’d plug in my headset, full cup of coffee in hand, and listen to the half a dozen conversations through my headset, while being briefed by the technician I was replacing. All this activity took just half an hour!

At times it seemed as though the only peace was up in the spacecraft we were tracking.

It was always a shock to drive along the narrow winding road through the rocks and the bush, and suddenly come upon the lighted buildings, with the gigantic floodlit antenna perched on the hill. The dazzling white structure looked like something from a sci-fi movie.

The dish antenna was the ‘ear’ for the sophisticated electronic signal-processing equipment that packed the many rows of cabinets inside the operations building. In winter the dish would fill up with snow. Sometimes during tracking operations the station, with the authorisation of Mission Control, had to ‘break track’ and tilt the huge dish right over to empty out the snow.

In 2000 the Australian movie The Dish, showed technicians playing cricket inside the Parkes dish — the ball would always return to the centre from anywhere in the ‘outfield’. Mike Linney, who operated the telemetry recorders, used to tell visitors, tongue in cheek, that our station staff used to skate around the Honeysuckle Creek dish in winter.

He says that most people believed him!

Because of this fictional movie (The Dish), many people think Parkes had a major role to play, and even downloaded the first images of Armstrong on the Moon. Parkes couldn’t even see the Moon when the astronauts emerged, but their TV picture was stronger and so was therefore substituted for Honeysuckle Creek’s picture after about ten minutes when they finally were in line of sight of the Moon.