Mankind’s journey to the Moon started with disaster.

The first manned mission (later called Apollo 1) was supposed to test the spacecraft that would ultimately take men to the Moon. The command module would carry three astronauts and the service module would supply the crew with oxygen and manoeuvre the craft in and out of lunar orbit.

In January 1967, during a trial countdown on the launch pad at Cape Kennedy, the spacecraft exploded in a burst of white fire that stunned everyone who saw it.

The three astronauts — Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee — died inside their spacecraft.

What had happened? Something horrifyingly simple — an electrical short circuit had produced a spark which ignited in an atmosphere of pure oxygen.

Honeysuckle Creek was not scheduled to track Apollo 1 — we were still checking our new equipment. But the tragedy brought home the risks and dangers associated with space flight. Even the tiniest error might mean death. I think that each one of us worried that we might be the person to make a crucial and potentially fatal mistake. It was frightening.

Although the spacecraft was redesigned, Apollo 2 and Apollo 3 were never launched. It was now mid-1967 — and President Kennedy had promised the world that the United States would have a man on the Moon by the end of the decade. Time was running out. NASA decided to test the whole gigantic three- stage Saturn V rocket instead of testing each section separately. It was an incredible risk — so many prototypes had already exploded on the launch pad, although no-one else had been killed. But the test worked. The unmanned Apollo 4 spacecraft orbited Earth in November 1967.

Apollo 5 didn’t carry astronauts, but it orbited Earth successfully. At Honeysuckle Creek we were preparing to track the spacecraft when it ventured out beyond Earth’s orbit — testing and retesting equipment, as well as the flow of information between the whole network of tracking stations around the world.

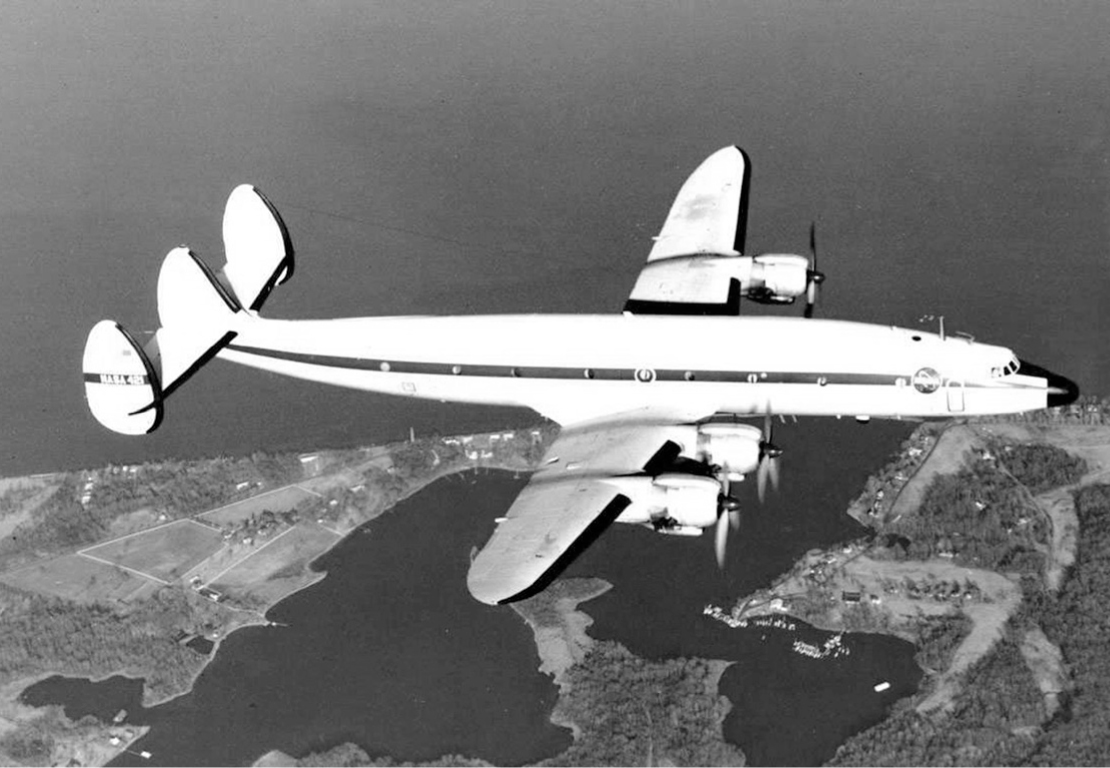

Finally NASA sent out a specially equipped simulation aircraft, the Super Constellation, that could ‘pretend’ to be an Apollo spacecraft while the Honeysuckle Creek station tracked it. The aircraft carried a powerful beacon light. Local radio stations got used to receiving calls about strange ‘flying saucers’ above Canberra every time it was used!

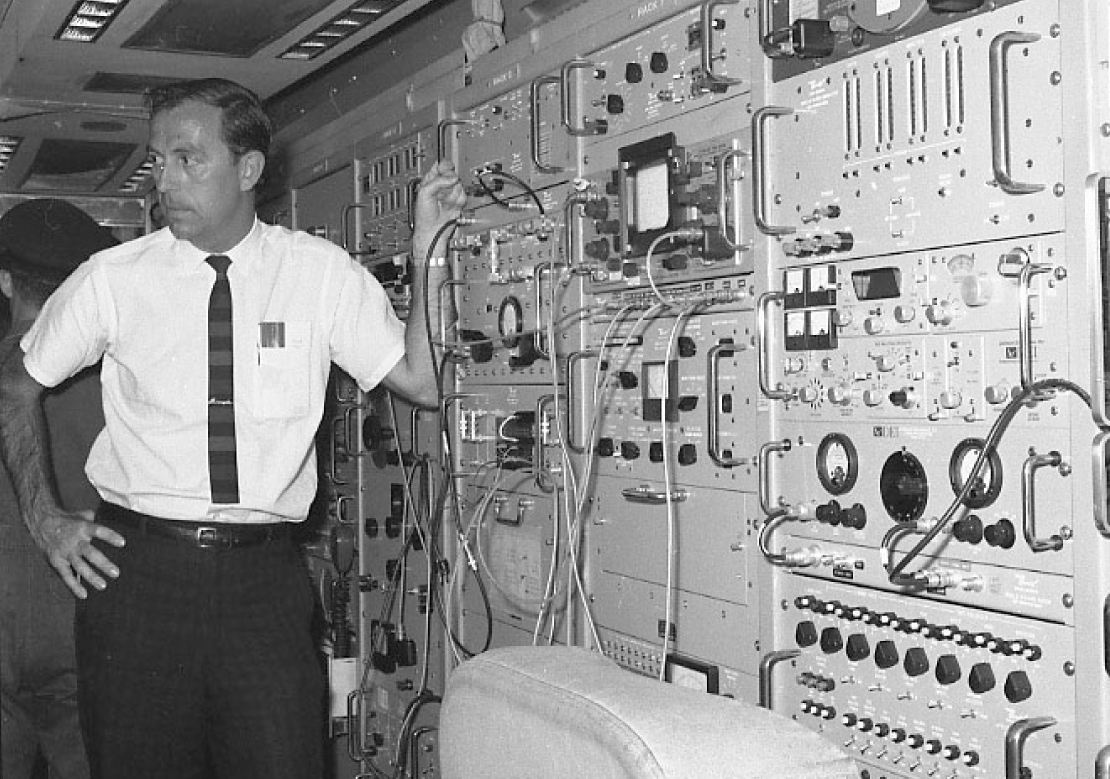

Simulations in the air. The interior of the Super Constellation showing the telemetry console and equipment.

HAMISH LINDSAY

NASA 421, one of three Lockheed Super Constellation aircraft that were used to test tracking stations around the world before each Apollo mission.

GODDARD SPACE FLIGHT CENTER

(The most regular NASA Apollo simulation aircraft to visit Australia was the old Lockheed Constellation Bataan that had been used by General Macarthur from 1948 to 1953. Its ‘Apollo’ crew had genuine American accents — our Aussie ‘astronaut’ accents were just no substitute for real American voices.)

There were also regular tests for any possible emergency. One of the best was when Laurie Turner, a supervising technician, pretended to have a heart attack in the middle of a simulation and training exercise. He was carried out on a stretcher, limp and lifeless — and it was so realistic that digital technician Eric Stallard was quite upset — and then furious when he realised it was just a practice ‘emergency incident’ to see if the rest of us could cope if one of them dropped dead in the middle of a mission!

The Fickle Finger of Fate was dreaded by everyone! It was made from a large piece of corrugated cardboard in the shape of a huge clenched hand with an extended index finger. It was double-sided and attached to a tall adjustable microphone stand on wheels. Whenever one of us ‘stuffed-up’ during a training exercise this huge finger would be wheeled up and pointed at the offender, accompanied by much ceremony, hilarity and embarrassment.

It was a lot of fun, but it was also deadly serious. Every member of the operational staff always wondered: what if it’s ‘my’ particular piece of equipment that fails? What if I were to cause the mission to be aborted, or worse, the loss of the astronauts?

Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station was fully operational by the time Apollo 6 was ready for launch. It was an unmanned spacecraft designed to test the giant Saturn V rocket that was supposed to take man to the Moon. But Apollo 6 had problems. When it was launched in April 1968, the spacecraft shook so violently it would have crushed any astronauts inside! Two of the five engines also mysteriously cut out.

Apollo 6 did reach orbit around Earth — and NASA announced that it had been successful. But we all knew that it had failed — and privately everyone was concerned.

Would Apollo 7 succeed? It would have astronauts on board. Would they be crushed — or worse, burnt? Would their engine fail? Would they drift in space long after their air and water had run out?

To our relief the redesigned command module operated perfectly — and this new design would be used for the next five years. The new TV cameras worked — and for the first time the team at Honeysuckle Creek was able to check out the TV circuits and voice channels with live astronauts talking with Mission Control.

Another novelty was getting live biomedical data — the astronauts’ heartbeats and respiration rates. This was really exciting. As the astronauts manoeuvred the spacecraft, practised their navigation skills with star sightings, or fired the main propulsion rocket motor, the telemetry data streamed through the Honeysuckle Creek computers at 100 samples per second — and we could see the excitement of the astronauts in the data we monitored.

Apollo 8 would also be manned. It would test the spider-like lunar module that would actually land on the Moon. By the spring of 1968, the building of the lunar module was running late, and the enormous new Saturn V rocket that was going to launch it had worked in only one out of two test launches.

The Americans were growing anxious that the Soviets were going to be first to have astronauts orbit the Moon. The Soviet Union had already taken terrible risks to secure a series of space records — the first man in space, the first two-man mission, the first woman in space and the first spacewalk. Then, in September 1968, the Soviets sent an unmanned spacecraft, Zond 5, around the Moon and back to Earth.

The Americans decided to change their plans — instead of just testing the lunar module, Apollo 8 would take three men around the Moon! And we would be part of the team who tracked them.

WHAT WOULD HAPPEN IF YOU WERE THROWN OUT OF A SPACECRAFT INTO SPACE?

Your brain would be immediately starved of oxygen and you would lose consciousness. Your lungs would then collapse, the air in your heart would bubble, and your blood vessels would rupture. You would die within a minute or so.