Around 1525, France began to view the world from a global perspective as it had never before or would ever after. The unique moment was marked less by the impact of the Columbian discoveries or the circulation of Amerigo Vespucci’s letters describing the nature of the New World than by the publication of Antonio Pigafetta’s account of Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe in 1521—and by the return of Giovanni da Verrazano, the Tuscan sailor whom Francis I commissioned to find a northwest maritime passage to the Orient, from his first oceanic voyage. Having just discovered lands on the eastern seaboard of North America extending from Cape Fear to Newfoundland, he staked French claim to places of which the world had been unaware. Before 1525, French vessels had sailed north and west from Dieppe, Honfleur, and Harfleur (and soon after, Le Havre, a city the same king founded for the sake of oceanic trade and maritime defense) to the Grand Banks in search of codfish. They had gone—and would continue to go—west and south as well, to La France antarctique, mooring along the eastern coast of South America to be freighted with brazilwood, the base of a bright red dye vital to the textile industry, obtained at less cost and risk than by way of travel to the Orient.

Historians of everyday life in early modern France have countered that the discovery of the New World meant little to many people of the time. It was an abstraction or even a figment of the imagination in view of the immediate and difficult task of living; gossip about newly found lands and an expanded planet was felt to be of little interest. Or was that really so? The ferment of humanism in Paris and other centers inspired greater reflection about the nature of belief and a fresh and renewed appreciation of geography. In centers of learning, manuscript and printed editions of Ptolemy’s Geographia were circulated and revised in accord with information and commodities coming, as it were, in bags and bushel baskets, en pleines bougettes, from lands east and west. The Alexandrian geographer’s projections of the world, although found wanting in view of mapping based on maritime experience, nonetheless carried authority in the universities.1 And thus, it is said, the sense of the globe obtained from a reader gazing upon a folio volume propped on a bookstand was far from what the observers of coasts and shores or of winds and stars had known or shown on their marine and portolan charts. Yet in the decade from the middle years of the 1520s to 1535, a uniquely “French global” sensibility emerged from humanists learning of the oceanic voyages. Theirs was what might be called an anthropological moment in which mathematical abstraction and a will to encounter the world coincided. As a result, the new “global” spaces appeared less to be the object of colonial design, as in Iberian policies and practice, than one for which alterity and unknown peoples and spaces were appreciated with inquisitive delight. At stake in what follows is not the idealization of the moment, but a treatment of its articulation in a body of graphic and textual matter comprising much of its difficult and conflicted legacy.

In the 1520s, writers witnessed a new and changing aspect of the globe and its representations. The medium of the printed book cast doubt about the nature of the world in which it was delivered. Unlike a manuscript, it could go anywhere and meet readers of unforeseen disposition in any variety of places. With the new mobility of type and woodcut images, the book often strove to become an imago mundi. Writers, well aware of the virtues of the medium, quickly called attention to maps, sometimes referring to them and at other times describing or even tipping them into their works. Among others, Geofroy Tory included a world map by Pomponius Mela in an itinerarium he issued in Paris in 1512. Two years later, in Venice, Alessandro Vellutello set into the prefatory matter of his edition of Petrarch’s Rime sparse a striking map of the area of Provence that the poet and his beloved Laura had known. Antonio Pigafetta’s Relation of 1525 incorporated images of the places Magellan and his crew had encountered. In the 1530s, touristic guidebooks of cities were designed to accompany city views and thus anticipated Michelin and Fodor four centuries before their fact. Thanks to Benedetto Bordone, the new and flourishing isolario or book of islands set maps of portolan inspiration into the prose of cultural geography. Writers and cartographers found themselves in active exchange.

In this context, two interrelated and complementary but very different works comprise what Monique Pelletier has recently called “cartographic culture,” in which mapmakers, though they may or may not have been directly associated with poets and writers, bore sustained impact upon them.2 Belonging to the codes, idiolects or even the sensoria of learned and popular strata of French society, cartographic forms infused materials belonging to different traditions. It is more than a coincidence that the writing of Rabelais (1492?–1551), an author exploiting the graphic and spatial dimensions of printed language, would find ways of touching and tasting the world at large—indeed of grasping its global proportion—through the works of the preeminent cosmographer, mathematician, and polymath Oronce Finé (1494–1555). At stake is a lecture de regard, a reading of the humanistic writer with and through the mathematician and cartographer in ways that help us to gather a sense of the nature of the ambient, indeed “global” world as it became known in France after 1525.

Le sphere du monde and the Cordiform Maps

A view of France seeking to reach outward to the world at large is magnificently manifest on Oronce Finé’s great single cordiform map of 1534. Designed to offer to the spectator a view of the world as it could be seen in a single glance, the heart-shaped map is made from a circular image of the globe. Between the north and south poles the cartographer drew a meridian close to the Canary Islands, the site to the east of which is found the old world and its continents and to the west some newly discovered and many still unknown lands. He pushed the poles southward so as to yield two great arcs that move up from the apex at the north, outward and then down to the austral point at the bottom of the globe.3 Within their perimeters are drawn, in the eastern sphere, the continents of Europe, Africa, and Asia; the extended shape of the Mediterranean as Ptolemy had described it; the western and middle reaches of Asia. To the west are found, first, the islands and coastline of North America that Columbus, Vespucci, and Verrazzano had discovered; then, the coastline of South America and, beyond its western littoral, the expanse of the eastern Pacific suggested to join its western component that reaches to the Indian Ocean and to form a sluice between the southeastern coast of Africa, the island of Madagascar and the northern shores of the immense—but still undiscovered—continent of Antarctica. It flows into the south Atlantic and reaches the narrows of Magellan that Antonio Pigafetta, who had sailed with the Portuguese circumnavigator, described in his account of 1525, recently published in Paris.

By following the boats, the viewer gains a sense of the voyage as Antonio Pigafetta had narrated it in the French edition of his account.4 A first ship is placed west of Portugal and north of the Canary Islands. Another, directly below, to the east of the Falklands, seems headed either to the coast or to the Straits of Magellan as they are named on the map. A third boat is located to the west of the Isthmus of Panama and the Pancras Islands, while a fourth, to its west, sails toward the Spice Islands along the same latitude. On the other sphere of the map a fifth vessel, situated on exactly the same latitude, points toward Madagascar. A ship fitted with oars floats to the west of the Cape of Good Hope while, to its west and north, a seventh vessel in the series is almost equidistant between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Equator.5

By simple and ingenious means the projection offers little distortion of the rotundity of the globe. It minimizes what, in his terse treaty of cosmography, Le sphere du monde (1551), Oronce notes about the art of describing the world, “lequel ne peut estre comprins en une seule figure, sans notable difformité [which cannot be projected as a single figure without significant deformation]” (56v). Yet une seule figure it is, with minimal distortion, that happens to bring France remarkably close to the new World that Verrazano had claimed in the name of Francis I. Here Oronce’s map tells much about the tricky relation of cosmography to geography. What is “global” may—or may not—be tied to what properly belongs to “French” geography. In the inaugural chapter of Le sphere, drawing on Ptolemy and his recent commentators, Oronce offers a pellucid definition of the world. Under the title “Quele chose est le monde: & des deux principales parties d’icelui en general [What thing the world is, and of its two principal parts in general],” he writes:

Le Monde est la perfaitte & entiere composition de toutes choses, & le vray image [sic] & admirable artifice de la divinité, de grandeur incomprehensible, & neantmoins limitee, & orné de tous les corps & especes de creatures qui peuvent en nature. La description duquel, est proprement appellee Cosmographie: comprenant souz soy la premiere partie d’astronomie, & la geographie, c’est à dire la fabrique, & rationcination tant du ciel que de la terre. Le monde doncques a deux principalles parties: comme il appert tant par la continuelle experience, que par raison naturelle. (f. Ar, stress added)

[The World is the perfect and entire composition of all things, and the true image and admirable work of divine art, of incomprehensible size, yet nonetheless limited and decorated with all the bodies and species of creatures that can be found in nature. The description of which is properly called Cosmography: including in its purview the first part of astronomy, and geography, in other words, the construction and ratiocination at once of the heavens and of the earth. The world thus has two principal parts: as it appears as much by continual experience as by natural reason.]

Cosmographers are those who countenance the world in view of the heavens in which it is situated. Geographers count among those who study what appears (appert) before them through experiment and experience. Oronce futher underlines the distinction: “Cest à sçavoir, la region elementaire [est] tousiours occupee à la generation & corruption de toutes choses, tant vivantes que non vivantes [In other words, the elementary region is always taken up in the generation and corruption of all things, both organic and inorganic]” (f. Ar). In this context the terrestrial sphere resembles what Montaigne later calls une branloire perenne, a mass in which things at once grow and decay and whose living and inorganic elements are in continual toss and stir. Its dynamic force is shown in a series of three images, the first that isolates the “elementary region” of the planet at the center of the circle enclosing the “celestial part of the world,” the second the world as seen in a diagram of its four elements and equal number of forces (aridity, heat, humidity, and cold) in their various degrees of attraction and repulsion. The final image in the montage given in the early pages of Le sphere portrays the earth surrounded by its flux of forces. A world map, drawn to illustrate the cohering presence of land and water, displays the three known continents (the Holy Land at the axis of the circle) and much of Antarctica within a scalloped rendering of the atmosphere, itself set within a great concentric circle of fire. The minuscule diagram displays a stable world in the midst of ambient and radiant and even mystical force.

In Le sphere, the map of the known world is given less to identify its regions than to establish its stable character in an expanding frame of transformation and discovery. The European, African, Asian, and Antarctic continents are shown responding to the observation concerning hydrography, that

l’eau n’environne point rondement & entierement toute la terre: ains est respandue par divers bras, traits, & conduits (que nous appellons mers) tant au dedens, que au tour d’icelle [:] car il estoit necessaire, que aucunes parties de laditte terre fussent descouuertes pour le salut & habitation des vivans: ainsi q’uil [sic] a pleu au createur, prevoyant la commodité de toutes choses. (f. 2v; emphasis added)

[Water does not at all surround the earth roundly and entirely: rather, it is spread about through diverse arms, lines and conduits (which we call seas) as much within as around it: for it had been necessary for some parts of the said earth to be discovered for the salvation and inhabitation of living beings: thus was the creator’s pleasure in foreseeing the commodity of all things.]

God, who foresees the “commodity” of all things, is pleased to see that lands have been discovered for the salvation and habitation of living beings. Celestial cosmography, a discipline built upon mathematics and astronomy, but also given to contemplation, can be implied as leaning toward colonial ideology. The shoreline of the North American continent on the single cordiform map can be read from such a perspective. The Fiftieth Parallel north is drawn cutting across the Armorican Peninsula of France and extending over the Atlantic Ocean before meeting the eastern seaboard of North America, where it cuts through the middle of the first word of the formula Terra Francesca nup[er] lustrata that extends laterally—in order to be discerned without difficulty—along the shores that Verrazzano had discovered and named from Virginia up to Newfoundland.

French claims are implicitly laid upon a continent from which extends an immense peninsula at a right angle to the Terra Francesca. Titled Baccalear, the mass reaches to a point below and near the southern tip of the narrow island of Greenland. A dorsal column of taupinières, or mountains depicted as molehills, follows the arc of the Arctic Circle to a plain to the west of the Hudson. If the western edge of the new world mixes information gathered prior to Cartier’s voyages with the cartographer’s fantasy, the peninsulas of Canada and the Terra florida at a right angle seem to be extensions of an imaginary divider whose hinge would be close to the mouth of the Hudson. By its very shape Canada beckons France and vice versa, its great mass having as its counterpart the Armorican Peninsula that points toward it. The history of French fishing fleets that sailed to the Great Banks is implicitly marked. Long before documented evidence of 1504, French fishing vessels, in quest of cod, ventured as far as the Canadian shores. The claim they had made to the region was less for land than fish in the waters to the west of Baccalear.6 Oronce’s map, it can be inferred, translates into topographical terms a project that refers to maritime commerce (and, indirectly, fishing) as a means to configure a westward movement. Beyond and below, from the areas under the banner of France, a viewer of then and now can countenance the crossing of the American continent across the “River of the Sacred Spirit” (the Mississippi) and inland to “Catay” and beyond.

The form and design of Le sphere du monde and its Latin original, De mundi sphaera, sive Cosmographia, tend to confirm this. The fifth book takes up wind and hydrography “selon l’art & usage des hydrographes & mariniers, tant pour l’usage de naviger, que pour la composition des cartes marines, qui contiennent seulement les ports, limites, & lieux maritimes de la terre avec les isles qui sont en la mer [according to hydrographers’ and mariners’ art and use, both for the use of navigation and for the making of marine charts that contain only the earth’s ports, limits and maritime sites with the islands that are in the sea].”7 When correlated with perspective, geography veers toward a practical usage by which the world becomes measured and its surface navigated.8 In this way, the depiction of the earthly sphere carries a connotation of hope, just as the heart-shaped map, drawn in the context of Pauline ideology of “faith, hope and charity,” central to the Gallican theological and political agenda under Francis I, remains both a depiction of the known world at the time of its issue, a complete geographical register of names and places, and also as a prayer, a project and a wish to see and sense the world in all of its immediate and wondrous entirety.

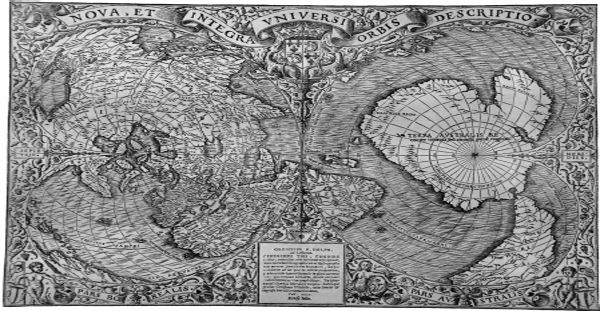

Surely the single cordiform map that Oronce noted (on the map of 1534) he had drawn in 1519 before completing its revised version in 1534 is crafted for the purpose of contemplation, too, of the relation of its spectators with the lesser and greater worlds in which they are found. Between its conception—no doubt in dialogue with Peter Apian’s 1530 map of the same form—and its final execution, the cartographer drew and printed a bicordiform map of even greater consequence (see fig. 2.1, p. 41).9 Accompanying the Parisian edition of Johann Huttich and Simon Grynaeus’s Novus orbis regionum ac insularum veteribus incognitarum (1532), the map was designed to fold into the pages of the book recounting voyages, among others, of Columbus and Vespucci to the New World. The innovation of this map is shown first, in the fold pleated to fit the confines of the book in which it is placed. The crease runs along the middle or slightly to the right of the axis (running vertically at the tangent of the two spheres) to emphasize a balance obtained from the distribution of masses of land and water. At the poles a strong contrast is made of an arctic archipelago, where waters sprinkled with islands are surrounded by land, with its counterpart, an austral continent bordered by ocean. A map executed according to the geometer’s vision, it offers the most accurate—and seemingly empirical—rendering of Antarctica prior to its discovery two centuries later. As on the single cordiform map, Baccalar might possibly be Labrador.10 It also extends toward Europe, emphasizing once again a prototypical tectonic theory by which the tip of the Canadian peninsula seems to have drifted away from it origin in the Bay of Biscay (a movement today visible in the affinity of the shoreline of Newfoundland with the western coast of France).

Oronce noted that his bicordiform map was drawn according to coordinates obtained from a méthéroscope géographique, an astrolabe equipped with a magnetic compass.11 Like the shape of its counterpart, the presence of the Molucca Islands (to the right of the center) and the narrows between Antarctica and the southern tip of South America show that the projection is also inspired by Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe and, given the place names and of the Antilles through which the Tropic of Cancer is drawn, Hernán Cortez’s conquest of Mexico.12 Yet one of the most striking aspects is the bipolar and even binocular aspect of the whole, stressed in the effects of light and shadow from the concentration, dispersion or absence of toponyms and relief all over and about the masses of land and water. Place names are concentrated in Europe and the Mediterranean and along the coastline of Africa. They scatter into extensive ridges of mountains in Asia and North America, an intermediate area between the dark and densely marked regions of western civilization and the white space of the unknown that is appropriately titled, in consonance with the observations made in Lesphere and other texts: “Terra Australis Recenter inventa sed nondum plenè cognita.” All over the map, the names and lines depicting the orography and rivers of the world translate less a will to reify or possess the globe than to establish a positive geographical relation with what is unknown about it.

Although the world is shown as a whole in a single glance and gaze in the single cordiform map, the Nova, et integra universi orbis descriptio splits the earth down the middle, leaving the old world and the recent discoveries to the left and the southern hemisphere (and what little is known of it by way of Magellan) to the right. The great banderole bearing the title at the top of the map pulls the two sides together where integra unfolds on one side of universi and orbis on the other. The waft of the banderole brings out of the background a diadem and an escutcheon counterpoising the dolphin of the Dauphiné (Oronce’s birthplace) and the fleur-de-lis of France. Surrounded and supported by two royal salamanders (the totem of Francis I), they set the nation and the world in a frame of creative form. The double perspective marked by the two poles from which the lines of each heart are sprung (to the left and right) causes the map to be read with emphasis on its depth of field. By virtue of convexity implied by the meridians thrusting from the axes, each heart seems to push its central area into space. The viewer, whom Oronce addresses as the reader, can fancy that when the map is folded backward it would approximate a terrestrial globe.

The “mathematician-geographer’s keen appreciation of the beauty of form”13 owes to a sense of discovery and of the unknown that goes hand-in-hand with the emphasis that the craft of the map brings to hydrography and, thus, to oceanic travel in the wake of Magellan. The limits of the world begin to be drawn, and so too are the itineraries that would be frayed and followed to develop global exploration and commerce. The maps show that the unknown is recognized as such and that by being discerned and located it becomes an object of contemplation. Especially pertinent is that the two heart-shaped creations are intimately tied to the circumnavigation of the globe and that paradoxically, as if their fortune belonged to poetic irony, the cordiform contour melds documentary evidence and a world-vision with the craft of allegory.14 Like the substantive and rebus, lesphere, with which Oronce titles his vernacular edition of De mundi sphaera, the two maps betray a sense of metaphysical and geographical hope as it was understood in the Pauline ideology that drove the Gallican cause from the beginning of the reign of Francis I.15

Pantagruel

On these grounds, the maps and the cosmography stand as complement and counterpart to Rabelais’s Pantagruel of roughly the same moment. A work that mobilizes Pauline sentiment through appeal to popular literature treating of giants of times past, Pantagruel draws on the anonymously authored Cronicqs du roy Gargantua, whose copies sold “like hotcakes” (or fouaces, as they are called in Rabelais’s sequel, Gargantua). The young doctor of medicine had been in contact with Erasmus and with Evangelical prelates at the time he had the idea of using the mold of a mock-epic to contain and to disseminate material of greater grist—haulte graisse—bearing on belief, on the writing of history and, foremost, on France in the global sphere. For the ends of Pantagruel, Rabelais at once drew on the cartographic register of Thomas More’s Utopia and on Lucian’s riotous dialogues and reflections on the art of chronicle. Late in the comic novel the narrator-scribe ventures into the mouth of his eponymous master. The bicordiform world map (1531), completed and published a year before Pantagruel (ca. 1532–33), leaves a discernible trace upon the episode in which Alcofrybas Nasier (anagram of François Rabelais), the erstwhile chronicler of Pantagruel’s formation and good deeds, avoids getting drenched by rain when his giant master and his army are bivouacked during a campaign against the Almyrodes. Pantagruel extends his tongue to shelter his men; Alcofrybas ascends to get his bearings and soon treks into his mouth before encountering “de grandz prez, de grandes forestz, de fortes et grosses villes non moins grandes que Lyon ou Poictiers [great fields, large forests, strong and stout cities no smaller than Lyons or Poitiers].”16 He walks alone, exploring strangely familiar places that have—by virtue of the narrator’s penchant to compare places of the world he has just departed with those of this new and unknown territory—a familiar air. In what would be a primal scene of anthropology or cultural geography,17 Alcofrybas meets his “first” man, a native, who happens to be a cabbage planter.

Et le premier que y trouvay, ce fut un bon homme qui plantoit des choulx. Dont tout esbahy luy demanday. Mon amy que fais tu icy? Je plante (dist il) des choulx. Et a quoy ny comment? Dis je. Ha monsieur (dist il) chascun ne peut avoir les couillons aussi pesentz qu’un mortier, & ne pouvons estre tous riches. Je gaigne ainsi ma vie: & les porte vendre au marché en la cité qui est icy derriere. Jesus (dis je) il y ha icy un nouveau monde. Certes (dist il) il n’est mie nouveau mais lon dit bien que hors d’icy ha une terre neufve ou ilz ont & Soleil, & Lune: & tout plein de belles besoignes: mais cestui ci est plus ancien.18

[The first whom I met there was a guy who was planting cabbages. And totally astonished I asked him: my friend, what are you doing here? I plant (he says) cabbages. And for what and how? I say. O yeah, Monsieur (he says) not everyone can have balls heavy as a mortar, and we can’t all be rich. Thus I make my living: and I bring them to be sold at the market in the city just behind over here. Jesus (I say) there’s a new world here. Surely (he says) it’s not new at all, but rumor has it that outside of here there’s a new land [terre neufve] where they have Sun and Moon: and it’s chock full of all kinds of things: but this one here is older.]

Here and elsewhere in the comic novel, Alcobrybas, constantly on the road, meets one character after another. Contrary to those who travel by constructing itineraries from toponyms on contemporary maps, he encounters not a cannibal—with which northern Brazil is identified on Oronce’s and Holbein’s maps in Grynaeus—but a local who could be from the author’s own Chinonais in the Touraine.19

Alterity transmutes into a happier familiarity, and so too does a locale into a world of cosmographic proportion. When the narrator meets the stranger—“le premier que y trouvay”—he is totally—tout—astonished. The typography indicates that where the narrator “finds” indigenous people in this other world, he implicitly (according to the etymology of trouver, to “turn about”) goes around a man and a place of an unknown but familiar (hence, in the best Freudian sense, uncanny) character. In the context of war and wandering the coincidence of tout and trouver yields a visible echo of où: where, in a context determined by the story of Jonah or by a comic reminiscence of an intestinal episode in Teofilo Folengo (in the Merlini Cocai) in the sum of things are the narrator and the planteur de choulx?

The question, posed in the gap between a locale and a whole prompts the extraordinary exclamation, “Jesus [I say/said].” Reference to Creation comes with the name of the Son of God adjacent to the deictic marker locating the site whence the speaker speaks (between parentheses) that could be both present and preterit: I knew [Je sus], Jesus I say, here there is a new world. . . . When studied as a speech-act the sentence underscores an inhering parataxis. To be sure, it concatenates with others in the discourse, but it also becomes also an invention of its own character. The voice astonished by the presence of a new world can be directed toward the cabbage planter but also to the speaker himself as a form of inner dialogue or meditation. It can also, when scanned in reverse, be addressed to Christ (such that the je may be the rival or the gladly profane counterpart to the sacred figure): “Jesus, I tell you, here there is a new world,” in other words, a world of which “you” (Christ) have been unaware.

In this moment in which the world is turned topsy-turvy, the nouveau monde can refer both to the Columbian discoveries and, given the topography of the text, to the author’s own Touraine. It can also echo a sense of anxiety of “whereness” in a visual rhyme, within the printed characters of ou and on by which mirroring and inversion are visible: where is this new world, and how can it be found or turned about? The narrative that follows begs the question. Taking note of his informant’s words, Alcofrybas decides to follow the planter’s path to the city of Aspharage, where he sells his cabbage. Along his way he encounters a fowler (whom he calls a companion before he ever meets him) who casts a net to catch errant pigeons.

Or en mon chemin [j]e trouvay un compaignon: qui tendoit aux pigeons. Auquel [j]e demanday: Mon amy d’ond vous viennent ces pigeons icy? Cyre (dist il) ilz viennent de l’autre monde. Lors [j]e pensay que quand Pantagruel baisloit, les pigeons à pleines volées entroient dedans sa gorge, pensans que fust un colombier. Puy entray en la ville, laquelle je trouvay belle, bien forte, & en bel air.20

[Now on my road I met a companion: who cast his net for pigeons. To whom I asked: My friend where do these pigeons here come from? Sire (he said) they come form the other world. Then I thought that when Pantagruel yawned, thinking that it was a dovecote, great flocks pigeons flew into his mouth. Then I entered the city, which I found to be quite beautiful, very strong and attractive too.]

In a world where originary encounters of needs take place over and again, the pigeon-catcher would be an “other,” an avatar of the cabbage-planter, inserted to confirm that the first meeting truly took place. The encounter with the latter confirms the amiable nature of the farmer in the former. In Rabelais, as in a great body of anthropological literature, the staging of a scene of encounter asks both its players and the spectators or readers who witness the event to reckon with its alterity. They are to be sought or found both in the gist of the account and in the printed medium that conveys it. Correlated here, the two registers of the scene—the narrative and the printed form—qualify the presence of a new world. The pigeons are ensigns coming from places afar and without, but at the same time they are also evidence of things and places from the New World, notably because colombe and colombier cannot fail to connote Colomb, both pigeons that carry messages and the areas of the Columbian discoveries.

Up to this moment in the chapter the narrator’s itinerary bears some resemblance to that of his master. Passage and entry, either granted or thwarted, have been keynote. Except for the Almyrotes, the inhabitants of all the cities of Dipsody have joyously given to Pantagruel the keys to all of the cities he has encountered. Now Alcofrybas is granted passage into the city of Aspharage despite the threat of garlic-ridden plague in Laryngues and Pharingues, which are compared to two maritime cities, Rouen and Nantes, from which ocean travel is begun. He then inches his way through mountain passes where he finds a graciously Italianate landscape. He soon descends, no doubt between the molar and bicuspid teeth, to get lost in a forest in which a group of brigands mug and rob him. After arriving in a land of Cockaigne, he soon finds employment by sleeping and snoring. Reporting to the senators and magistrates of the country he learns that from their standpoint the (transalpine) people from “over there, beyond the teeth” (les gens de delà les dents) are by their very nature unmitigated thugs. In these words Alcofrybas infers that his hosts share an ethnocentric bias on the world at large. All of a sudden a tension of cosmography and topography inspires speculation about geography and diplomacy:

From which I recognized that just as we have countries on this side and on that side of the mountains, they too have them on this side and on that side of the teeth. But on this side the land and air are much better. There I began to think that what they say is really true, that one half of the world doesn’t know how the other half lives. Seeing that no one had yet written of this country counting more than twenty-five inhabited kingdoms, not counting deserts and a great lagoon: but I’ve compiled a large book titled the Story of the Gorgias: for I’ve named them thus because they live in the gorges of my master Pantagruel’s throat.21

The mountainous landscape that separates one world from another, as might the Alps the French from the Italians, recalls impressions that soldiers and travelers feel in passage from one world to the other. The description mirrors many of early printed accounts and maps affiliated with commerce and pilgrimage, whether itineraria listing place names to suggest routes to follow, or documents in the order of Jacques Signot’s Totale et vraie description de tous les passaiges, lieux et destroictz par lesquelz on peut passer et entrer des Gaules of 1515.22 In fact, the same surveyor’s topographic map includes seven alpine passes on the borders of France and Italy.23 Because the imaginary “world” of the chapter includes a gaping mouth opened upon a horizon seen from what could be an eastern clime—Jerusalem and the Holy Land remaining an ideal point whence to gaze westward—the remark to the effect that one half of the world has no inkling about how the other half lives includes in its scope, like a cordiform map, an “old” and a “new” world.

The cosmographical perspective reveals that Oronce’s maps are a paradigm for the narrator’s reflection on the condition of knowledge about the globe. The map and text imply that the new dimensions of the world, paradoxically liberating and confining, require contemplation about how to contend with alterity. Like the revised versions of Ptolemy’s mappae mundi, Oronce’s double sphere indicates that the physical world has its limits, but that what is found within them, much as the innards of a human body under the gaze of a student of medicine, remains unknown and needs to be both qualified and appreciated as such. The sphere on one side, whose circular surround is the equator, that bends inward (or outward) to (or from) either of the poles, is separated from the other. Except for Scythia, northern Asia, and the polar mass, the lands in the sphere to the left are generally known. On the sphere to the right the southern peninsula of Africa displays the source of the Nile and the lands of the fabled Prester John; the middle and lower portions of South America, labeled (according to Vespucci) America, include a land named “Canieales” (that on the single cordiform map is spelled “Canibales”); and Antarctica, “recenter invienta,” claimed not to be fully known, is a dominant blank mass.

The map and the text grant privilege to or even welcome the unknown where they also seek to set a measure to it. In a psychoanalytical idiolect of our time, it can be said that they contend with the unknown through two types of introjection. Developed by Nicolas Abraham (1987), the concept signifies a spatio-verbal process by which a person copes with anxiety. He or she uses intermediate forms of language, including inner or outer speech, to mediate the threat of alterity. The force of speech that cannot name or control what is felt as a menace, whether from within or without the body, circulates in areas are felt to be behind the lips and in or around the throat. In doing so, the person manages fear by suspending the menace of what is other in the palatal and buccal regions. Energies that contend with alterity are set afloat in the mouth so as to be felt and tasted, and to a degree assimilated in bodily rhythms. They are not, in Abraham’s words, incorporated—that is, encrypted, repressed, or confined—in its foreign and strange within the body itself.

The chapter of Pantagruel that Erich Auerbach studied in the name of “the world in Pantagruel’s mouth” can now be understood as a genial introjection of the doubts and fears that would come with the idea of a world whose orders are not what they have been thought or previously schematized. It holds or lets float the fantasy of un nouveau monde in its own buccal fantasy, and it reflects on the way that a local or even national vision of the ambient world does not have perspective enough to entertain—that is, to introject—what is other when a new sense of the limits of the globe and the commerce of “globalization” are at stake.

If, as the founder of psychoanalysis once proposed, a “flight of imagination”24 allows the viewer of Rome to see the various strata of the city in a single image, what Oronce Finé offers in his binocular fancy can be construed as a form of visual introjection. The cosmographer draws a map replete with information past and present, drawn from Ptolemy’s conceptual geography and the accounts of recent oceanic travel. From its double axis (and an implied ellipsis that could result from further coordination of the points) are generated thirty-six meridians in an almost apical fashion: the world grows embryonically from these points and, as the eye seeks to discern the composition of land and water on one side, the other stands in view. The Nova, et integra universi orbis descriptio accounts for how an otherwise invisible or unknown half of the world can be seen from both in and outside of that in which the viewer would be placed. Its own ocular shape makes it appear to stare back upon its viewers and to beg the question about whence they are gazing upon the globe.

It is well known that Oronce was, like Rabelais, a polymath. Mathematician, surveyor, geographer, astronomer, poet, translator, and cosmographer, he was also an astrologer who employed the art of divination to establish a sense of the world and its movement in the heavens.25 The soothsayer’s art is tied to an uncanny sense of the presence of occult and diurnal forces, of things familiar and other, both in the terrestrial world and its heavens. Lesphere du monde makes connections between cosmography and astrology through the attention it brings to the force of the stations of the zodiac on the ecliptic band that surrounds the terrestrial sphere. The spirit of Pauline “hope” (with faith and charity) invested in the title is evinced the composition and execution of the maps. In a marked fashion, they are cartographic representations of the world as it is imagined expanding and growing from shapes as Aristotle and Ptolemy had conceived them. They are also components of a prayer made for order and a balanced, indeed enduring rapport with things known and unknown, especially in the context of shards of information being gathered from other regions of the globe.

A global relation with Rabelais can be further projected. No matter if, when writing the thirtieth chapter of Pantagruel, the author may have really gazed upon Oronce’s bicordiform map in Grynaeus: rather, in cartographic culture in general, the moment of tumult in matters of belief and geography from the 1520s and early 1530s signals mystical anticipation of the French nation in a world whose edges and borders are drawn with lines of creative doubt. Rabelais ends Pantagruel on a note in which pleasure and ambivalence are mixed. Alcofrybas is tired of writing. The “registers” of his head are clouded under the influence of “this septembral purée” he has imbibed along the way. Ending his Lucianesque chronicle, he promises much more. At the forthcoming fair of Frankfurt,

[V]ous verrez comment Panurge fut marié, et cocqu des le premier moys de ses nopces, et comment Pantraguel trouva la Pierre philsophale, et la maniere de la trouver et n’en user. Ct comment il passa les mons Caspies, comment il naviga par la mer Athlantique et deffit les Caniballes, et conquesta les isles de Perlas. Comment il espousa la fille du roy de Inde nommé Presthan. . . . Et mille aultres petites joyeusetez toutes veritables. Ce sont belles besoignes.26

[You’ll see how Panurge was married and cuckolded in the first month of his nuptials, and how Pantagruel discovered the Philosopher’s stone, and how to recover it and to use it. And how he went over the Caspian Mountains, how he sailed over the Atlantic and defeated the Cannibals and conquered the Perlas Islands [on the south side of the isthmus of Panama]. How he married the daughter of the king of India named Prester John. . . . And a thousand other veritable bits of joy. These are wondrous labors.]

The task of the comic narrator is to tender promises, all fanciful or fraught with delusion, meshed with the art of prediction. Panurge, the trickster and companion who enters the world from limits of Christendom, will be consumed with anxiety. Pantagruel will become a real philosopher and a traveler who reaches the New World and wins over the regions Oronce had named on his maps of the same moment. While the predictions are paraphs, they are also signposts, projective maps as it were, of an open-ended composition. Points of narrative return and departure, they comprise fantasies of itineraries that the very French and very Christian subjects of the novel will make in the world at large. They are also elements of satirical divination vital to what some readers see as the design of a greater project.27 Pantagruel will discover the world over and again, as has Alcofrybas, while Panurge, it is implied, will stew in his own juices.

The end of Pantagruel takes pains to aim the reader west and into regions on either side of the South American continent. Set in the mode of divination, the passage is close in tone and tenor to his Pantagrueline prognostication, a work first published in Lyon in 1532 or 1533, and then redone for the years 1535, 1537, and 1538 prior to affording significant inclusion in the Oeuvres complètes of 1553. In its first edition, in lettre bâtarde, under the title, Pantagrueline prognostication certaine, veritable, et infallible. Pour l’an mil. D.xxxiii, nouvellement composee au prouffit et advisement de gens estourdis et musars de nature, par maistre Alcofribas, architriclin dudict Pantagruel (Lyons, ca. 1532), a woodcut image portrays a man of knowledge embraced by a fool. The latter casts a malicious gaze upon his somewhat diminutive companion while he points skyward with his right arm. A personified sun (who seems to look earthward with suspicion) occupies the upper left corner of the frame, while a sliver of the moon (its face, staring at the sun, seen in profile on its inner arc, is found in the upper left corner). Three birds fly in the atmosphere, one resembling a stork and the others possibly a magpie and kingfisher. Three six-sided stars are adjacent to the spokes of black rays cast from the circle of the sun. Dense parallel and herringbone hatching providing shade and depth to the two men’s robes is elegantly matched by the lines defining the rolling contour of the landscape in the background. An enigmatic sphere rests on a piece of ground (marked by five parallel hatches), in the lower left corner, in front of the two men. The arc of another ball is shown at the lower edge, suggesting (just as the learned man’s feet are out of frame) that the world extends well beyond the window of the woodcut.

Alcofrybas, designated by way of a word found in both François Villon (as architriclin) and the Gospel according to Saint Jean (architriclinus), is his master’s maître d’hôtel.28 In view of the woodcut, the chronicler or comic impresario of Pantagruel is now an astrologer-fool whose wit and wisdom owe—the text will soon make clear—to the paradox of inebriate clarity,29 a condition that in the prologue to Gargantua (1534–35) Socrates will soon personify. A founding irony of the woodcut is that as the astrologer is said to decipher the obscure signs of the heavens, track the movements of the planets, and taste the character of the atmosphere he nonetheless looks away from the sky and directly toward the man on whose eyes the world might be reflected. His portrayal bears special meaning in respect to the context of frontispieces of contemporary manuals of cosmography. In the latter Ptolemy—soon mentioned as an authority in the Almanach pour l’an 1533—is usually shown looking skyward in earnest contemplation of the heavens. Here the fool-as-astrologer occupies the place otherwise dedicated to the Alexandrian cosmographer. His costume anticipates a theme of geographical satire, later made famous in Jean de Gourmont’s satirical view of the face of the fool as a world map staring at the viewer, while the bells at the tips of the rabbit ears of the headpiece are figured as little “globes” or worlds dangling in front of the firmament.30

Shown in the text to be a devout believer, the fool brings benediction to the reader under the sign of Christ. The composition of the text and image underscores the contradiction. The legend to the woodcut serves as a transition and even a clever shift from one register to another: “De nombre dor non dicitur, je nen trouve point ceste annee quelque calculation que jen aye faict, passons oultre, qui en a si sen defface en moy, qui nen a sy en cherché. Verte folium [Of the golden number it is not said, I cannot find any this year, whatever calculation I’ve made, let’s move on, may whoever is thus be effaced from me, who here has not here sought anything within. Turn the page].”31 Meticulous placement of the imperative in Latin in the lower corner of the title page (recto) begs the reader to go to the other side, where, immediately visible and legible, verso, is Christ’s name: “Au liseur benevole Salut et paix en Jesuchrist” (1v). The comic figure gives way literally to his sacred other on the other side of the page. Thus: Verte folium. The act of turning the page, whether backward or forward, reveals a true piece of folly and, concomitantly, a foolish piece of truth. He or she who sees the scene of madness in the woodcut and textual composition recto turns into the person who reads the mad words of truth sanctioned verso in the name of Christ. The movement from one folio to the next, the process of reading and seeing the prognostication is part and parcel of the enigma and its truth. The two players in the dialogue are two sides of a figure who might be called, in homage to the macaronic and rebus-like registers of the language of the text, a “green fool” and a devout “a folly to be seen.”

The framing of the satire as it goes from one side of the folio to the other sets the work in the toss of religious turmoil. The comic almanac proposes to correct abuse brought to the art of observation and unfortunate falsification of true knowledge. The first words of the textual component stage a dialogue that can be invested into the image of the two interlocutors seen in the title. Not unlike the meeting with the cabbage planter in Pantagruel’s mouth, a scene of encounter or of apprehension of things unknown, marked as they are with the presence of Christ—“Jesus (dis-je) ily a ic y un nouveau monde”—inaugurates the reflections to follow.

The incipit is rife with the issue of the differences felt between humanistic knowledge said to be known and that which, like the topographer’s, is gained by aural and ocular experience. Its poetic echoes require ample quotation:

Considering infinite abuses being perpetrated because of a pile of Prognostications from Louvain made in the shadow of a glass of wine, I have presently calculated one, the surest and most reliable ever seen, as experience will demonstrate to you. For surely, seeing that the Royal prophet says psalm 5 to God. You will destroy all those who utter lies, it is not a slight sin thus to lie in good faith, and together to abuse the poor world eager and curious to learn of new things. So forever have been the French, as Caesar has written in his Commentaries and Jean de Gravot in his Gallic Mythologies of what we continue to see in France, day in and day out, where the first words directed to people newly arrived from foreign lands are: what’s new? Do you know anything that’s new? What’s astir in the world? And so many who are attentive that often get angry at those who come from far without bringing little bags of news, calling them oafs and idiots. If then, as they are prompt in asking for information, so also are then ready to believe whatever they are told. Ought not trustworthy people be paid to stand at the gates of the Kingdom to serve no end other than to examine the information brought forward, to know if it’s really true? Yes, surely. And thus did my good master Pantagruel throughout the whole country of Utopia and Dipsodia.32

In the incipit the consideration of the first word (signaled by a historiated letter C) pertains to the coincidence (con-sidereal movement) of stars and planets in the heavens from the standpoint of a given place—Lo(uv)ain—whence false prognostications are issued. The narrator, referring to the chapters of Pantagruel noted in the paragraphs above, who takes pride in prevarication warns of its sin. He restages the type of scene that marked the encounters both in Pantagruel’s mouth in chapter 32 and far earlier on in the comic fiction, as in the paired encounters with the Limousin student (chapter 6) and Panurge (chapter 9).33 A native meets a stranger in an originary and forcibly reiterated encounter with things or persons unknown. It is almost axiomatic to say that those shown asking questions are avatars or doubles of Alcofrybas asking of news from the cabbage planter and the fowler. The true/false quality of the scene bears on geography insofar as the fabled inhabitants of Gallia are evoked by way of Caesar and the imaginary author of a name close to Rabelais’s Chinonais. A scene of France and of Frenchman contemplating the nature of an expanding world is staged through a parodic rewriting of the popular almanac that from its beginning bears cosmographic trappings.

The end of the chapter and the matter of those that follow insist on how a sense of distance or binocularity must be brought to the text in the same way that the experience of encounter, as shown above, merits consideration when information is obtained from foreign lands:

Ce que sera dit au par sus, sera passé au gros tamys a tors et à travers, et par adventure adviendra ou par adventure n’adviendra pas. Dung cas vous advertis. [Q]ue si ne croyez le tout vous me faictez ung maulvais tour dont seres puniz icy ou ailleurs. Or mouschez vos nez petiz enfans et vous aultres vieux resveurs affustez vos bezicles et pesez bien ces mots.

[What will be said, further, from above will be sifted through a big screen, one way and the other, and will happen or perhaps will not happen. In every case you’re warned. If you don’t believe it all you’re playing a dirty trick on me, for which you’ll be punished here or elsewhere. So, kids, wipe your noses and you, you old dreamers, adjust your spectacles and weigh well these words].34

In the presence of the globe and heavens seen in the image the screen or sifter is implied to be an armillary sphere, the embodiment of hope of the mechanism of the world, lesphere du monde, in all of its veracity. And the attribute of the dreamy old man, the pair of bifocals, belongs to the woodcutter, the tailleur d’histoires or “tailor of stories” who wears magnifying glasses to draw images of the world. That he dreams implies that he figures in a rebus in which unconscious meanings float about or, better, are introjected both in his character and in the printed text. The implied relation with the cosmographer, now with the added virtue of binocularity, could not be clearer.

Conclusion

The world that Oronce portrays is that which Rabelais inverts. Mathematical irony confirms the point when Rabelais composes his Almanachs of Lyons on the heels of the Prognostication. He locates the city of their origin at the intersection of the coordinates of latitude and longitude that Oronce, correcting and refining Ptolemy, employed to situate the city on his great map of France of 1535. From this evidence a literary historian would comfortably imagine that Rabelais had pored over Oronce’s maps while composing his Pantagruel and related material. Where the one, the serious humanist who produces knowledge of the limits of the world as it has never before been shown, is the earnest and truthful cosmographer, the other, on the verso side, would be the satirical writer making madness and mayhem of the same material. Oronce would be a learned cabbage-planter and Alcofrybas the inquisitive traveler who meets him while treading on the map of his tongue. Or else Oronce would be an astrologer from whom Alcofrybas would learn the art of prognostication vital to a many-faceted vision of the world. In the matrix of cartographic culture, however, they are of a similar conscience: both bear a keen sense of a world that is “globalizing” as it never had before, and both welcome the strange and new forms that accompany its expansion.

Notes

1. Père François de Dainville, S.J., La géographie des humanistes.

2. Monique Pelletier, “National and Regional Mapping in France to About 1650,” 1500.

3. The map makes use of the spherical triangle and the spherical projection described in “Comment la huitieme, & quarte partie, & la moitie du globe terrestre, peuvent estre commodement reduittes en plate forme [How the eighth, and fourth part, and the half of the terrestrial globe can be easily reduced a flat form],” chapter 7 of book 5 of Le sphere du monde, proprement ditte cosmographie, composee nouvellement en françois . . . par Oronce Fine, natif du Daulphiné, lecteur mathematicien du treschrestien Roy de France en l’université de Paris (Paris: Michel Vascosan, 1551; Harvard Houghton Library *FC.5.F494.Eh551s). This work is a translation of De Mundi Sphaera, which witnessed editions in 1533, 1541, 1542, 1551 (reviewed and emended), 1552, and 1555. It is also a printed variant of the manuscript L’esphere du monde: Proprement dicte cosmographie (Paris, 1549; Harvard Houghton Library MS Typ. 57).

4. Simon de Colines, an editor with whom Finé was affiliated throughout much of his career, published Pigafetta’s relation. J. Theodore Cachey Jr., ed., Antonio Pigafetta: The First Voyage Around the World, 1519–1522, xlvii.

5. Noteworthy is that in Giovanni Cimerlino’s 1565 copperplate copy of the same map, all but the seventh boat in the implied scheme are absent. Having become a fact of history forty years after the event, the sign of Magellan’s voyage disappears. A draft of Cimerlino’s map can be found and navigated in the digital resources of the Harvard Houghton Library.

6. Samuel Eliot Morison, The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages, 254. The quest for fish is noted on Jehan Rotz’s map of the area in his great Boke of Hydrography of 1542 (Helen Wallis, ed., The Maps and Texts of the “Boke of Idrography” Presented by Jean Rotz to Henry VIII).

7. F. 56v. By slight contrast De Mundi Sphaera (Paris: Simon de Colines, 1542) develops the material with different illustrations (ff. 81v–84v), without the rubricated wind map printed and drawn in the French translation. The Latin edition exhibits a compass rose and the lines of the marteloio system, essential to navigation, at the end of the sixth chapter (f. 85v). Reference is made to the Harvard Houghton copy (Typ. 515. 42. 393f).

8. At the same time (1542) Oronce writes and illustrates De Mundi Sphaera he also edits and illustrates—also at Simon de Colines—Charles de Bovelles’s Livre singulier & utile, touchant l’art et pratique de geometrie. The work brings mathematics into the realm of everyday life. Furthermore, the manuscript copy of L’esphere (dated 1549; Harvard Houghton Library Ms. Typ. 57) underscores the point in its dedication to Henry II.

9. See Apian’s map in Rodney Shirley, The Mapping of the World: Early Printed World Maps, 1472–1700, 68–69.

11. Frank Lestringant and Monique Pelletier, “Maps and Descriptions of the World in Sixteenth-Century France,” 1465.

12. See Roger Hervé, “Essai de classement d’enssemble, par type géographique, des cartes générales du monde.”

13. Lestringant and Pelletier, “Maps and Descriptions of the World,” 1467.

14. The cordiform map disappears before the end of the sixteenth century and is revived four centuries later (George Kish, “The Cosmographic Heart: Cordiform Maps of the 16th Century”; Tom Conley, The Self-made Map: Cartographic Writing in Early Modern France, 134; Giorgio Mangani, “Abraham Ortelius and the Hermetic Meaning of the Cordiform Projection”; Giorgio Mangani, Cartografia morale: Geographia, persuasione, identità, 127).

15. See Anne-Marie Lecoq, François premier imaginaire, for the development of relation of the Gallican ideology to Pauline scripture in the early years of the reign of Francis I.

16. See Rabelais, Oeuvres complètes, 331. With the exception of the first edition of the Pantagruéline prognostication, reference to Rabelais will be made to this edition.

17. Tom Conley, “Rébus de Rabelais,” 678.

18. Rabelais, Oeuvres complètes, 331.

19. In Mimesis, Erich Auerbach underscores the familiarity of the stranger whom Alcofribas encounters.

20. Rabelais, Oeuvres complètes, 331.

22. John Hale, “Warfare and Cartography, ca. 1450 to ca. 1640,” 725.

23. Pelletier, “National and Regional Mapping,” 1500 and fig. 48.14.

24. Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, 70.

25. Bernd Renner, Difficile est saturam non scribere: L’herméneutique de la satire rabelaisienne, 229.

26. Rabelais, Oeuvres complètes, 336.

27. Robert Karrow, Sixteenth Century Mapmakers and Their Maps, 174–75; Isabel Pantin, “Altior incubuit animae sub imagine mundi.”

28. Rabelais, Oeuvres complètes, 1704.

29. Roger Dadoun, “Il n’y a d’ivresse que sexuelle,” 12–13; Marie-Madeleine Davy, “La ‘sobria ebrietas,’” 114–15.

30. Monique Pelletier, Cartographie de la France et du monde de la Renaissance au siècle des lumières, 14.

31. Rabelais, Pantagrueline prognostican, f. 1r.

32. Rabelais, Pantagrueline prognostican, f. 1r.

33. Conley, The Self-made Map, 153.

34. Rabelais, Pantagrueline prognostican, f. 1r; Oeuvres complètes, 924.

FIGURE 2.1 Oronce Finé, bi-cordiform world map (1531), Nova et integra universi orbis descriptio.