1

Get Real Security from Social Security Retirement Benefits

Over the years, you’ve paid taxes—lots of taxes—to fund your retirement. And now it’s finally time to collect! Social Security offers a pot of gold at retirement, there just for the asking. Unfortunately, older Americans miss out on a lot of money that is rightfully theirs, just because they don’t understand their rights. Don’t feel bad—most lawyers, accountants, and other so-called experts don’t have the foggiest idea how Social Security works, either.

In this chapter we explain the secrets of the Social Security retirement program and we’ll give you dozens of “gems” to fill your retirement treasure chest. Get all you’re due—don’t settle for less.

ELIGIBILITY

How do you know whether you qualify for retirement benefits? If your answer is yes to both of these following questions, you are eligible.

• Did you work in jobs that were covered by Social Security?

• Did you work long enough to earn the required number of work credits?

What Jobs Are Covered?

Your job was covered if the employer paid Social Security taxes, or if you were self-employed and you paid Social Security taxes. Most older Americans are covered. But you may not be able to cash in if you worked for:

• The federal government before 1984. (You are probably covered by Civil Service retirement, discussed in Chapter 12.)

• A nonprofit organization before 1984. (You may be covered by a private pension plan instead of Social Security; see Chapter 6.)

• A state or local government agency. Some belong to the Social Security program and some do not. (Check with the agency.)

• Clergy. The clergy generally will be eligible only if they elected to be covered.

• A railroad. (You are probably covered by the Railroad Retirement pension program, discussed in Chapter 13.)

• Yourself. Before 1951, self-employment was not covered by Social Security. (We hope you created your own retirement fund!)

• A household employer. For example, if you cleaned houses or mowed lawns for 20 years, but your employer never paid Social Security taxes, your employment won’t be covered.

How Much Work Time Gets You Qualified?

If you are 63 or younger in 1992, you will need a total of 10 years of work—40 credits—in all jobs that were covered by Social Security. You generally get one credit for each quarter-year (three months) worked—four credits in a year.

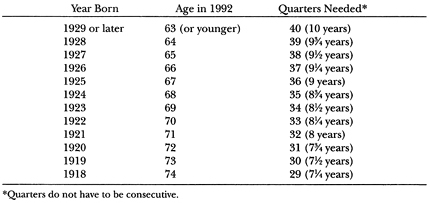

If you are 64 or older in 1992, you can get Social Security with fewer than 10 years of covered work. Table 1.1 shows the number of credits you’ll need.

TABLE 1.1

Number of Credits Required for Retirement

How Do You Earn Credit?

To receive a credit, you must have earned a minimum amount of money on the job. Until 1978, Social Security gave you one credit for each quarter-year (January–March, April–June, July–September, or October–December) that you earned $50 or more. That shouldn’t have been too tough to reach—it’s only about 77 cents per day! Even very low-paying jobs or part-time work probably earned you credits from Social Security.

Since 1978, the rules have made it even simpler to qualify. Instead of looking at your earnings in a quarter-year, Uncle Sam now gives credits based on earnings over the whole year. The amount of earnings needed for each credit is listed in Table 1.2.

TABLE 1.2

Earnings Needed for Each Credit

Year |

|

Amount Needed per Credit* |

|

||

1978 |

|

$250 |

1979 |

|

260 |

1980 |

|

290 |

1981 |

|

310 |

1982 |

|

340 |

1983 |

|

370 |

1984 |

|

390 |

1985 |

|

410 |

1986 |

|

440 |

1987 |

|

460 |

1988 |

|

470 |

1989 |

|

500 |

1990 |

|

520 |

1991 |

|

540 |

1992 |

|

570 |

|

||

* No more than four credits can be earned in a year.

Four credits is still the most you can earn in a year. Example 1 shows how this works.

EXAMPLE 1

In 1978 you earned $1,000 in January and February, and then you stopped working. Your reward: four credits ($1,000 ÷ $250 = four credits). It makes no difference whether you earned the money in 1 month or 12 months. But if you had earned $1,000 in January and February of 1977, you would have received only one credit because all your earnings were in one quarter-year.

GEM: Get “Extra Credits”

Do you have enough credits to qualify for Social Security retirement payments? Most people don’t give any thought to this question until they’re ready to retire—and by then it may be too late. If you check your Social Security credits before retirement is at hand, you may be able to earn enough “extra credits” to cash in.

EXAMPLE 2

You are age 60 and no longer working. You would like to start taking Social Security retirement benefits in two years. You’ve got your Personal Earnings and Benefit Estimate Statement from Social Security, and you have a total of 32 credits. Unfortunately, you need 40 credits, so you don’t have quite enough to get any retirement checks.

Since you checked early, rather than waiting until the last minute, you should be able to earn eight extra credits so that you can start taking retirement checks as planned. It won’t take much to earn the extra credits—a part-time job, working a couple of days per week, should be more than enough.

Checking your earnings record early and, if necessary, getting enough extra credits to qualify for retirement benefits could easily add thousands of dollars to your annual income. The sooner you check your record, the more time you’ll have to fill in any gaps—now is not too soon!

You can check your earnings by sending for your Personal Earnings and Benefit Estimate Statement from Social Security. We will talk more about this statement in the next few pages.

* * *

GET YOUR “CREDIT RATING” FROM UNCLE SAM

Now that you qualify for benefits, the next question is: How much will you receive (either now or in the future)? The Government will tell you an amount, but if there’s a mistake, your failure to catch it now could cost you thousands of dollars every year of your retirement life!

Your monthly Social Security retirement checks will be based on the number of years you worked and on the amounts you earned during those years. The longer you worked and the more you earned, the higher your checks will be. The exact amount is calculated based on a complicated formula—did you expect anything else from the Government?

Most people just take what Social Security gives them—no fuss, no questions asked. If the Government says you’re supposed to get $400 a month, that must be correct, right? If you agree, then we’ve got some swampland in Florida to sell you! Of course Washington makes mistakes.

Couldn’t Social Security’s records reflect the wrong amounts of your earnings? What if the Government’s computer has a glitch and makes an error in computation? The result could be disastrous! By checking your file at Social Security and promptly correcting any errors, you might save yourself a lot of money and heartaches.

Jeepes, Creepes, Get Your “PEBES”

Your first step to verifying your Social Security account is to obtain a Personal Earnings and Benefit Estimate Statement (PEBES) from the Social Security Administration. The PEBES will provide you with important information, including:

1. A year-by-year list of all your earnings covered by Social Security

2. Estimated retirement benefits at age 62, 65, and 70

3. Estimated life insurance and disability benefits

You can get your PEBES by filling out the PEBES request form, available at your local Social Security office or by calling (800) 772-1213. The form is easy to fill out. Make sure you spell your name exactly as it appears on your Social Security card. Return it to the Social Security Administration at the address on the form. Several weeks later, you’ll get your PEBES.

Even if you’re already receiving Social Security retirement checks, get your PEBES. It will show your annual earnings in jobs covered by Social Security, which is crucial information in determining whether you are getting the right amount.

Check Your Earnings Record

You know you worked in 1963 and 1964, but no earnings are shown on your PEBES for that year. And your earnings are listed at $10,000 for 1970, but your total wages were at least three times that amount. Take a close look—do the earnings listed for you on your PEBES match your actual income?

Believe it or not, there really could be a mistake. Since the calculation of your benefits is based on the earnings listed for you in Social Security’s files, mistakes in the listed earnings will mean mistakes in the amount you are paid.

What could go wrong? Check the Social Security number on the PEBES—maybe you were sent the wrong one. Or maybe your employer failed to accurately report your wages. Or maybe you were self-employed and earnings weren’t reported under the right Social Security number. Or maybe one year you changed jobs and something got lost in the shift. Or maybe your employer didn’t take out FICA (Federal Insurance Contributions Act) taxes and you never noticed. Or maybe, just maybe, Social Security screwed up!

Here’s a real-life example of what could happen: For many years, Sally ran her own business, always mindful to pay her Social Security taxes. Her accountant—we’ll call him Jack—sent in tax returns for Sally under the wrong Social Security number, and her earnings were posted to the wrong account. When Sally retired, she received much less than she was entitled to, until the problem was finally caught and straightened out.

Mistakes are often made when an employee works two jobs or makes a job change. Many employers are ignorant of the tax laws. Your employer, knowing that you have a second job, may assume that you will pay the maximum FICA (Social Security) tax on the other job, and decide not to take any FICA tax out of your earnings. Or when you switch jobs, one employer may assume FICA taxes on your earnings were fully paid by the other employer, and so again he’ll decide not to take out FICA. In either case, you may find—much later—that at least some of your earnings for that year weren’t counted by Social Security. Why? Because Uncle Sam only gives you credit for earnings on which FICA was paid.

Correct the Mistakes—Get Credit Where Credit Is Due!

A mistake in your earnings record, no matter the reason, can be very costly! Immediately report it to Social Security. There are three reasons for the urgency.

First: You generally only get 3 years, 3 months, and 15 days from the date of the error to submit a correction. For example, if your earnings for 1989 were reported incorrectly, you have only until April 15, 1993 to notify the Government of the error. The time limit is not iron-clad; there are a number of exceptions. For example, if you can produce a W-2 form to show a mistake was made or that an employer failed to report some or all of your earnings, there is no legal limit on how far back you can go. But you’ll always have a far easier time getting mistakes corrected within the legal time period.

GEM: Report Your Employer If He’s Not Taking Out FICA

If you are still working and your employer isn’t taking out FICA, call the IRS immediately—call anonymously so your employer won’t know who squealed. The IRS will then launch an investigation. If you are right, the IRS will collect the FICA tax from the business, and you’ll get your proper Social Security credits—and you may wind up never actually having to pay the FICA tax yourself!

* * *

Second: The longer you wait, the harder it will be to get proof of your earnings. You have the burden of showing Uncle Sam that a mistake was made on your PEBES and to establish the proper amount of your earnings.

The best evidence of your earnings is your pay stubs or a W-2, which should always be kept. Never throw out W-2s! A W-2 can be used to correct your PEBES, even if the employer is out of business. And there’s no limitation period—a W-2 can be used to prove your correct earnings at any time.

If you don’t have your old W-2 forms from 10 and 20 years ago, good luck in trying to track them down. Employers are required to retain these employee records only for three years. While some larger businesses, like Ford or GM, might keep records for a longer period of time, smaller businesses almost surely will not. Your employer may not even be in business anymore, and then the records of your earnings are probably long gone. After the employer’s records are destroyed and the statute of limitations is up, you’ve usually got big problems.

Your federal income tax returns may help you prove the amount of your earnings—but retrieving the tax forms is no picnic, and sometimes may be impossible. For tax returns filed within the last six years, request Form 4506 from your local IRS office. Older returns themselves are not available, but information from your returns—including earnings—may be available by writing to the IRS.

Third: Social Security may take from six months to as much as a year to correct your records. The sooner you find and take steps to correct a mistake, the sooner you’ll get the added money in your checks.

If you are still working, check your PEBES regularly—every two to three years is wise. As we’ve said, mistakes are harder to correct the longer you wait.

GEM: Get the Tax Man to Pay You!

When you check your PEBES, you may find that too much FICA tax was taken out. In that case, you’re in for an added benefit—Uncle Sam will refund the overpayment.

Here’s what to look for: Your PEBES lists the earnings on which FICA tax was paid. Now turn to Table A in Appendix 1. Compare the amounts you earned to the maximum amounts subject to FICA tax each year, listed in Column B. Earnings over these maximums should not have been subject to Social Security tax.

Your PEBES shows the earnings on which FICA was actually paid. For any year that your PEBES shows earnings higher than the maximum, you’ve overpaid the tax. For example, if you had more than one job in a particular year, you might find that you actually paid FICA tax on more than the maximum earnings.

EXAMPLE 3

In 1990 you worked for one company and earned $30,000 during the first half of the year. Then you switched jobs and earned $30,000 for the second half of the year from another company. Both employers withheld FICA tax on all of your earnings, because one employer didn’t know how much the other withheld. You ended up paying FICA tax on $60,000 of earnings—well over the $53,400 maximum. If you catch this mistake, you can get yourself a refund!

By checking your W-2 forms, you will see exactly how much FICA tax has been withheld. If you see that you paid FICA on too much of your earnings, claim a credit when you file your next federal income tax return. Contact a professional tax preparer for assistance. Don’t miss out—this is money in your pocket!

* * *

Figure Your Benefits

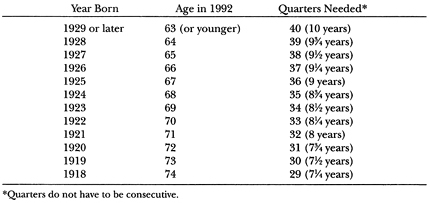

Even if your earnings record on the PEBES is accurate, you’re not clear yet. Again, it’s possible that there’s been some mistake in the Government’s calculation of your benefits. The Social Security Administration does a good job of computing benefits (a lot better than the IRS does in figuring taxes), but mistakes do occur—and you don’t want to be the one who loses out. Do yourself a favor by checking your benefits against Table 1.3.

TABLE 1.3

Monthly Benefits If You Retire at Age 65

Your Earnings in 1991

Table 1.3 gives you an estimate of what your payments should be if you begin taking benefits at age 65. The full age 65 retirement benefit is called the Primary Insurance Amount (PIA).

The figures in Table 1.3 are only estimates. They assume you have worked steadily throughout your career and have received average pay increases. You can get a much more accurate estimate of your benefits by using the tables in Appendix 1.

GEM: Get the Maximum with the Special Minimum

All right. You’ve obtained your PEBES, checked the calculation, and—to your horror—the amount of your benefits is unbearably low.

Social Security retirement benefits are supposed to provide an income safety net for older Americans. But for many people, especially those who worked during the 1950s and earlier and were paid very low amounts by today’s standards, the standard retirement program falls short. Since retirement benefits are based on prior earnings, many senior citizens risk falling through holes in the safety net.

Uncle Sam has taken steps to remedy this serious problem. Extra cash may be available to you under the Special Minimum Benefits Rule! Under this rule, the Government uses a special formula to calculate benefits for people who worked at low-paying jobs (covered by Social Security) for many years. Use Appendix 2 to see whether you are entitled to Special Minimum Benefits. Don’t miss out on this Golden Opportunity.

EXAMPLE 4

You started working as a secretary in 1945 and stayed at lower-paying jobs until 1975. From 1945 through 1950, you earned a total of $4,500. From 1951 through 1975, each year you earned from $900 to about $3,500 (amounts listed in Appendix 2, Table A). After 1975, you stopped working.

Now you’re 65 and looking forward to starting your Social Security retirement benefits. But when you hear from Social Security, you’re horrified to learn the amount comes to only $357/month.

That’s where most people stop. But that’s not where you should stop. Under the Special Minimum Benefits Rule, you should be entitled to $478/month—a full $121/month over your regular benefits!

* * *

GEM: Special Benefits for Our Oldest Elders

Even if you have no Social Security credits, you have one last chance to get a Social Security retirement paycheck. A special benefit generally is available, regardless of need, if you are either:

• A male, age 92 or older in 1992

• A female, age 94 or older in 1992

(Some credits will be necessary if you were born between 1896 and 1900.)

The benefit can come in handy: $173.60/month—$347.20/month if both spouses qualify.

WHAT’S THE BEST TIME TO RETIRE?

The question we hear most often is: “When should I start taking retirement benefits? Am I better off taking lower monthly benefits starting at age 62, or should I wait until I reach age 65, or maybe even age 70?” For most older Americans, early retirement offers a Golden Opportunity—waiting can be a costly mistake. Here’s the Golden Rule: Take the money and run!

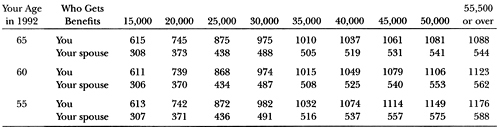

First, let’s give you a little background. At age 65 you can retire with “full” benefits. If you wait past age 65, you get “boosted benefits”—a higher monthly retirement check. You can start taking monthly retirement checks as early as age 62, but the amounts will be permanently reduced—and the reduction can be stiff. Benefits starting at age 62 will amount to only 80 percent of the sums you’d get by waiting until age 65. Table 1.4 shows the reductions for early retirement.

TABLE 1.4

Early Retirement Reductions

You Retire at |

|

You Receive This Percentage of the Full Amount Available at Age 65 |

|

||

62 |

|

80% |

63 |

|

86.67% |

64 |

|

93.33% |

65 |

|

100% |

The closer to age 65 you retire, the more you’ll get from Social Security; the closer to 62, the less you’ll get. Table 1.5 shows how to figure the amount of money you lose when retiring early.

TABLE 1.5

Use this formula to determine how much you’ll lose by retiring early:

1. Count the number of months between the date you intend to start benefits and your 65th birthday. Let’s say you want to begin receiving retirement benefits at age 63; this is 24 months early.

2. Multiply the number of months in number (1) by .5555 percent—that will give you the percentage by which your benefits will be reduced. If you take benefits 24 months early, your benefits will be reduced by 13.33 percent (24 x .5555%).

3. Multiply the percentage in number (2) by your full age 65 retirement benefit—that will give you the amount you will lose by taking early retirement benefits. If your benefits at 65 would be $800 a month, you would lose $107 (13.33% of $800) each month, or $1,284 per year, by choosing early retirement benefits at age 63.

Although early retirement is “punished” now, wait until you see what’s coming. Your friends in Congress have extended the “normal retirement age” for citizens who are now 54 or younger. In the future, retirement at age 62 will cost even more of your full retirement benefit, as shown in Table 1.6.

TABLE 1.6

Penalty for Early Retirement in the Future

You may also delay retirement past age 65, all the way to age 70. Each year you delay boosts your eventual retirement benefits. If you reached age 65 in 1992, your retirement benefits would get a 4.0 percent boost for every year past age 65 that you delay taking benefits. The delayed benefit boost is scheduled to go up, as Table 1.7 shows.

TABLE 1.7

Increases for Delayed Retirement

You Reach Age 65 in |

|

For Every Year Past Age 65 You Delay, Your Retirement Benefit Increases by |

|

||

Years prior to 1982 |

|

1.0% |

1982–1989 |

|

3.0% |

1990–1991 |

|

3.5% |

1992–1993 |

|

4.0% |

1994–1995 |

|

4.5% |

1996–1997 |

|

5.0% |

1998–1999 |

|

5.5% |

2000–2001 |

|

6.0% |

2002–2003 |

|

6.5% |

2004–2005 |

|

7.0% |

2006–2007 |

|

7.5% |

2008 or later |

|

8.0% |

Let’s summarize: your benefits are lowest at age 62 and highest at 70. If you start taking Social Security retirement checks before reaching 65, your payments will be reduced forever—they don’t go up when you reach 65 or 70. Why, then, would we recommend starting your benefits as early as possible? Our recommendation makes perfect “cents”—by putting you dollars ahead.

GEM: Take Early Retirement Money and Run

Let’s say your full retirement paycheck at age 65 would be $800 a month; if you waited until age 70, you’d get $960 a month (20% higher). So why are we telling you to lock in retirement benefits of $640 a month at age 62—33.3 percent less than you’d get at age 70?

Looking at figures like these, it’s not surprising so many older Americans fail to take advantage of the Golden Opportunity to cash in on early retirement. You can almost always do better by taking your money early. Examples 5 and 6 show why.

EXAMPLE 5

You decide to start your monthly $640 benefits at age 62, rather than waiting. Each month, you put the check into a mutual fund earning an average yield of 8 percent. By your 65th birthday, you’ve given yourself quite a present: an account worth $25,000.

At 65 you start pulling out the 8 percent yield—$167 each month. (Interest and dividend income do not reduce Social Security benefits.) Added to your $640 Social Security check, you’re getting $807/ month—$7 more than you’d be getting had you waited until 65 for your full benefits.

And don’t forget, you’ve got $25,000 in cash that you didn’t have before. That’s the Golden Opportunity of taking early retirement; it’s a gem that many older Americans miss.

When you get those ads in the mail telling you that you may have already won cash and prizes worth $25,000, don’t you get excited? Well, get excited by early benefits because Uncle Sam has a valuable prize for you. Even if you invest the money in CDs or some other investment earning 6 percent, you still come out ahead taking the money early. At 65, you’d have a pot of $24,500. Add the $123/month in interest to your $640/month Social Security check and you have a total of $763/ month—just under the $800/month if you had waited.

EXAMPLE 6

Take a look at how early retirement compares to late retirement at age 70.

Let’s take the same facts as in Example 5. You start taking $640 checks at age 62, and deposit them in CDs (at 6%) until you reach age 70. At that time, your account has reached a whopping $76,000. If you withdraw the interest (at 6%), $380 per month, and add that to your $640/ month benefits, your income will total $1,020—compare that to the $960 monthly benefit you would be entitled to receive by waiting to age 70. Early retirement has even more luster when compared to delayed retirement.

If you need (or want) to keep working past age 62, then starting retirement benefits at 62 won’t be an option. (We’ll explain why combining work and retirement doesn’t pay off here.) But many older Americans are not working full time past age 62, yet they’re holding off taking their retirement benefits because they know their benefits will go up over time. That’s usually a bad idea.

Even if you don’t need the money at 62, take it and put it into CDs, stocks, bonds, or some other safe investment. Better yet, use a tax-deferred retirement plan like an IRA (see here). That requires some self-discipline. We suggest setting up an account whereby your retirement checks are deposited directly, so as to reduce any temptation to use the money early.

Taking the money early is important for another reason. Not only will it give you a cash bonus, but you’ll be assured of getting something from all your years of paying Social Security taxes. Too many people, waiting until 65 or 70 to start their benefits, die and get nothing. Let’s look back at Example 5: If you died at age 65, your family would get the $25,000 from your early retirement checks. If you had waited to collect full benefits, your entire Social Security benefits would be lost (though a surviving spouse might get a slightly increased future benefit).

Aren’t we ignoring the impact that added years of earnings will have on your retirement benefits? Don’t higher earnings increase future benefits? The answers are yes and yes. We are ignoring the impact of earnings on future benefits—for a good reason: For people who have worked most of their lives, a few years of added earnings don’t add much to retirement benefits.

EXAMPLE 7

You turned 62 in 1987. You worked throughout your adult life receiving average pay increases and your 1986 pay was $25,000. Your monthly benefit at age 65 would be $879 (including cost-of-living increases). Let’s say you worked another three years, still receiving average pay increases. At age 65, your benefits would have “skyrocketed” to about $892/month—an increase of only $13/month. You can see that a few additional years of toil doesn’t increase benefits much. And over the three years, you will have paid thousands of dollars extra in FICA taxes on your earnings.

Remember hearing your elected officials say that Social Security is like a private pension—the more you put in, the more you will take out? You should know by now that if the news comes from your elected officials, chances are you’re not getting the whole story. As Example 7 demonstrates, your added benefits probably will not be enough to cover the additional taxes you pay into the system.

Now, this is not to say that you shouldn’t work past age 62. If you need the earnings, or if you love your job, by all means continue. But don’t be misled by your public officials: added work will not, in the long run, mean more retirement money in your pocket!

“ALL IN THE FAMILY” RETIREMENT BENEFITS

So far, we’ve been talking only about the worker’s getting retirement benefits. But others may also be eligible, during the worker’s lifetime, based on the worker’s earnings. These lucky people include the worker’s:

• Wife or husband who is 62 or older

• Wife or husband, under 62, if caring for a child under 16 or disabled

• Divorced spouse at least 62

• Unmarried children under 18 (19 if full-time elementary or high school student)

• Unmarried children 18 or over who were severely disabled before 22 and continue to be disabled (only children who have never married are eligible; once a disabled child has married, he or she is never again eligible)

• Stepchildren and grandchildren under certain conditions

Family members’ benefits will be subject to the Maximum Family Benefit, discussed here.

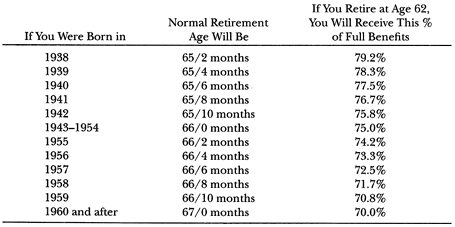

Spouse Retirement Benefits

Not only can you collect Social Security retirement benefits based on your own work record, but you can also cash in on your spouse’s record. Spouse benefits are available if you can answer yes to all three of the following questions:

• Is your spouse collecting Social Security retirement or disability benefits?

• Are you at least 62, or are you caring for a child who is: (1) under 16 or disabled and (2) entitled to benefits on your spouse’s record?

• Have you and your spouse: (1) been married to each other for at least a year, or (2) had a child together?

Spouse retirement benefits can provide a healthy boost for your income. At age 65, you can get half of your spouse’s full age 65 retirement benefit (PIA). If you (the spouse of the worker) retire earlier, your spouse retirement benefits will be reduced. If you qualify because you are caring for a young or disabled child, you will be entitled to 50 percent of your spouse’s PIA, regardless of your age. Spouse retirement benefits are listed in Table 1.8. If you retire early and start getting reduced spouse benefits, they will stay reduced for life—you don’t get a raise when you reach 65.

TABLE 1.8

Spouse Retirement Benefit

If You Retire at Age |

|

Your Benefits Will Be This Percent* of Your Spouse’s Full Age 65 Retirement Benefit |

|

||

62 |

|

37.5 |

63 |

|

41.7 |

64 |

|

45.8 |

65 |

|

50.0 |

Any age, caring for a child who is under 16 or disabled |

|

50.0 |

|

||

*Your spouse retirement benefits are reduced .694 percent for each month before age 65 you retire.

EXAMPLE 8

Your husband just turned 62 and has retired. You are 53 and your daughter, still living with you, is 15.

You, too, are eligible for benefits—not based on your age, but because of your daughter’s age. Since she is only 15, you get 50 percent of your husband’s full age 65 retirement benefit for one year (assuming you and your spouse have been married at least a year, or your spouse is a parent of the child).

Once your daughter reaches 16, your benefits end. But you can pick them up again when you reach 62—without any reduction for the amount you already received. At 62 you’d get 37.5 percent of your husband’s full age 65 retirement benefit.

When Is the Best Time to Retire If Eligible for Spouse Retirement Benefits?

You may have three options for Social Security retirement benefits: They may be based on your spouse’s work record only; your work record only; or both work records. Each option presents different issues. We’ve already talked about the best time to start taking benefits based on your own record alone (see here). Now we’ll take each of the other two situations.

1. You’re eligible for spouse benefits only. Let’s start by looking at a situation in which you don’t qualify for Social Security retirement benefits based on your own work record, but you can get spouse retirement benefits. This is the situation many older women, in particular, find themselves in today. When should you start taking benefits?

GEM: Both Spouses Should Take the Money Early and Run

If you are married, both you and your spouse should take the money and run as soon as possible. Examples 9, 10, and 11 show how you will be better off:

EXAMPLE 9

You and your husband are both 62. Your husband’s full retirement benefit at 65 would be $800/month; you don’t have any retirement benefits based on your own record. If both of you had waited to take your benefits until age 65, your husband would have received $800/month and you would have received $400/month (50% of his benefit), for a total of $1,200/month.

But you both started taking benefits at age 62: your husband receives $640/month (80% of $800) and you get $300/month (37.5% of $800), for a total of $940/month. You put the $940 monthly benefits into an investment paying 6%, and in three years the investment account has grown to more than $36,000. At age 65, you and your spouse begin taking the income (6%), which is $180 each month. Added to your continuing benefits, you’d receive $1,120, just slightly below the $1,200 you would have received if you both had waited to age 65.

But now you’ve got a bank account with more than $36,000! You are way ahead by taking the money early. Plus, if you or your spouse died, you’d have a pot of money that would not be there had you waited to collect full benefits. If you can earn 8 percent in your investment, you’ll be even better off—your total monthly income would increase to $1,180.

EXAMPLE 10

Your husband is 62 and you are 59. Your husband starts taking benefits immediately, so he gets $640/month (80% of $800, which would be his full benefits at age 65). You get nothing because you’re not yet 62. When your husband hits 65, you will have $24,500 extra (assuming 6% interest) sitting in the bank, accumulated from his benefits. The interest, $123 a month, added to his continuing $640 benefit, yields $763/month. You now become eligible for $300/month (37.5% of your husband’s $800 benefit), for a total income of $1,063 month.

Compare that to what your husband would have received if he had delayed taking any of Uncle Sam’s money until he reached 65. At that time, he would get $800 and you would get $300 each month—only $37 more. But without taking your benefits early, there would be $24,500 less sitting in a bank account with your names on it!

EXAMPLE 11

In 1986, your husband was 62 and you were 54. He took early benefits of $640/month at age 62, which he saved; when he reaches age 70 in 1994, he’ll have a whopping $76,000 in the bank (at 6% interest). The monthly interest that will throw off, at 6 percent, is $380. Added to his $640 continuing benefits and your $300 benefits (37.5% of your husband’s $800 age 65 benefit), your total combined income will be $1,320/month.

Now compare that to your income if your husband delays benefits until 70. His monthly benefit will be $920, and your benefit will be $300—total $1,220. That’s $100/month less than you have by starting early, and you won’t have that nice pot of gold worth $76,000 waiting for a rainy day.

2. You’re eligible for both spouse benefits and your own benefits. What happens when you are eligible both for spouse retirement benefits (based on your spouse’s work record) and your own retirement benefits (based on your work record)? Do you:

• Add the benefits together?

• Choose the higher?

• Apply some complicated formula that only public officials could create?

Remember, we’re dealing with the federal government here—the same government that created the Income Tax Code. So, obviously, the answer is 3. Generally you get no choice when you are eligible for both; Social Security applies a complicated formula that takes into account both your spouse and your own retirement benefits. Appendix 3 explains how to calculate your benefit when you’re eligible for both.

But there is a loophole that may open a Golden Opportunity to put added dough in your pocket. If you first become eligible for your own retirement benefits, and only later become eligible for spouse retirement benefits, you may choose either to: (1) start with your own retirement benefits and later switch to spouse benefits; (2) start with your own benefits and stay with them; or (3) forget your own benefits and wait to start spouse benefits. What should you do? The choice is clear-cut.

GEM: Start with Your Own Retirement Benefits, and Then Switch to Spouse Retirement Benefits ASAP!

When you qualify for your own retirement benefits, but you can’t yet get spouse benefits, start taking your own benefits as early as possible. Remember the Golden Rule: When it comes to Social Security, take the money early and run.

Then when you become eligible for spouse benefits, switch ASAP. You can never lose that way. Examples 12, 13, and 14 show how this works.

EXAMPLE 12

You are 62 and your husband is 61; your full age 65 retirement benefit is $200 and his is $800. You are not yet eligible for spouse retirement benefits, since your husband has not retired. Remember, he must actually retire and be 62 or older before you can take spouse benefits. But you can—and should—start taking your own benefits of $160/month (80% of $200).

The following year, your husband retires at 62 and gets $640/month (80% of $800). You may now choose to switch to spouse benefits, which would be $327/month.

Clearly, you’d switch from your own retirement checks of $160/ month to $327/month—that’s easy. But if you had waited to start any benefits until your husband retired, you’d start at age 63 with spouse benefits of $333/month—higher than the $327/month you’ll now get. Should you have waited? NO!

By taking your own retirement benefits at age 62 (which were the only benefits you could get at that time), you got 12 paychecks of $160 each. If you put those aside, you’d have $2000 in the bank in a year. Interest on that account at 6 percent would add another $10 each month to your spouse benefits of $327, for a total of $337. Had you delayed, your spouse benefit would have been almost the same—but you wouldn’t have $2000 sitting in your bank account!

EXAMPLE 13

Let’s say you are older than your husband—you’re 62 and he’s 59. Your full age 65 retirement benefit is $300 and his is $900. But you’re not eligible for a spouse retirement benefit because your husband hasn’t retired. So you take your own retirement benefit, which is $240/ month (80% of $300). For the next three years, that’s what you get. Since you put your checks in the bank, you have $9,200 (assuming 6% interest) by the time your husband hits 62 (and you are 65).

When your husband hits 62, he takes his retirement benefit, $720/ month (80% of $900). And you immediately make the switch to your spouse benefit—$390/month. Add to that $46/month of interest from your $9,200 account, and that brings your total income to $436/month.

If you had waited to take any benefits until your spouse reached 62, you’d start receiving spouse retirement benefits of $450/month (50% of $900—almost the same as you’re receiving anyway—but you’d have $9,200 less in your savings!

EXAMPLE 14

You and your husband are both turning 62 this year. Your full age 65 retirement benefit is $200 and his is $800. You reach that special age first and start taking your retirement benefits, based on your own work record, of $160/month; you can’t start taking spouse retirement benefits yet because your husband hasn’t retired. The next month, your spouse retires. You could—and should—immediately switch to spouse benefits, which would be $310/month (your husband’s full retirement benefit is $800/month).

What if you wait to switch to spouse retirement benefits to when you reach age 65? Until then, you would continue to receive your own $160/month retirement benefits. At 65, your spouse retirement benefits would be $360/month—$50/month higher than the $310/month you are receiving. Wouldn’t you have been better off taking your own lower retirement amount and waiting to switch until 65? NO!

Don’t forget—for the three years, from age 62 to 65, you will be getting $310/month, which is $150/month more than the $160/month benefits you otherwise would receive on your own. If you save those added funds until age 65, your bank account will be $5,700 fatter. That $5,700 would provide $29/month interest (at 6%) which, added to your continuing $310 spouse benefit, gives you total income of $339/ month—and your bank account is $5,700 richer!

If you qualify for your own retirement benefits before you can get spouse benefits, start with your own. But then switch to your spouse retirement benefit as early as possible. Don’t forget to reapply for spouse retirement benefits as soon as your spouse becomes eligible—Uncle Sam won’t start them for you automatically, and waiting may prove very costly!

The only time switching from your own retirement benefits to spouse retirement benefits doesn’t add cash to your pocketbook is when your own full age 65 retirement benefit is at least half of your spouse’s full age 65 benefit. In that case, switching to spouse benefits won’t increase your benefits. But because of the way benefits are calculated, you never lose by switching. See Example 15.

EXAMPLE 15

You are 62 and your wife is 59. Your full retirement benefit at 65 would be $400/month; hers would be $800/month. At age 62 you start taking your own checks of $320/month. You can’t take spouse retirement benefits because your wife isn’t yet eligible.

Three years later, your wife retires. Does switching to spouse retirement benefits add to your checks? The answer is no. But it doesn’t hurt, either. Your spouse retirement benefit would be the same $320/month under the Government’s formula.

You don’t have to be a mathematician to figure out how to take Social Security retirement benefits. Here’s the Golden Rule: If you first become eligible for your own retirement benefits, take them as soon as possible; then if you become eligible for spouse retirement benefits, switch at the first chance. You’ll come out dollars ahead!

When Spouse Benefits End

Your spouse retirement benefits end when:

• Your spouse dies. (You may then qualify for survivor benefits—see here.)

• You are divorced.

• Your child reaches 16 (if benefits were based on the child’s age).

• You die.

While you can’t do much about timing death or a child’s growth, you might schedule your divorce to maximize benefits.

GEM: “Split Decisions”—Time Divorce to Maximize Benefits

You don’t get spouse retirement benefits for the entire month in which the divorce occurs. So if you are divorced on April 30, you lose spouse retirement benefits for the entire month of April (unless you qualify for divorced spouse benefits—see below). A one-day delay, to May 1, could save you several hundred dollars (probably enough to pay for about ten minutes of the divorce lawyer’s time).

* * *

Divorced Spouse Retirement Benefits

When you get divorced, your relationship with your ex-spouse is ended for almost all purposes. Thank heaven for that, right? But a divorce does not end your right to cash in on your ex-spouse’s work record when you’re ready to retire. Thank Uncle Sam for that! You can qualify for spouse retirement benefits based on your ex-spouse’s work record if you can say yes to these four questions:

• Are you at least 62?

• Is your ex-spouse entitled to benefits (he’s reached age 62 or is disabled)?

• Are you unmarried at the time you apply?

• Were you and your ex-spouse married for at least 10 years?

In fact, you may be much better off divorced than married when it comes to Social Security. If you were married, you could only get spouse retirement benefits if your spouse had retired and started taking his own benefits. But you can collect on your ex-spouse’s record, even if he has not actually retired, as long as you meet the requirements listed above and the two of you have been divorced for at least two years.

If you qualify, you receive the same retirement benefits as you would if you had remained married (see here). And here’s more good news: you don’t reduce your benefits by deducting your former spouse’s current earnings (see here for the impact of a spouse’s earnings on benefits). Although his benefits may be reduced by his earnings until he’s 70, your ex-spouse retirement benefits will be figured as if he were not working.

Note: If you are remarried at the time you apply, you will not qualify for divorced spouse retirement benefits. But your ex-spouse’s remarriage will have no effect on your right to collect.

GEM: Getting a Divorce May Put Money in Your Pocket

While divorce is not something most people look forward to, it can sometimes provide a means of maximizing Social Security retirement benefits. If you are having trouble making ends meet, consider Examples 16 and 17:

EXAMPLE 16

You have remarried, and your new spouse, George, is working and earning a regular paycheck. You have no Social Security work record of your own, so even though you’re 62, you get no benefits. And you can’t qualify for divorced spouse benefits based on your first husband’s (Harry’s) work record since you’ve remarried. How about divorcing George? You might continue to live together and share your lives together. But by getting a divorce, you could fatten your pocketbook.

Let’s say Harry’s full age 65 retirement benefit is $1,000. By divorcing George, you would make yourself eligible for monthly divorced spouse retirement payments of $375 (37.5% of Harry’s full benefits) based on Harry’s work record. (You don’t even have to wait two years before starting to collect ex-spouse benefits if Harry is retired and not working.)

You don’t have to stay divorced long! As soon as you qualify for divorced spouse benefits, you can remarry George and keep your ex-spouse retirement benefits based on Harry’s work record. You only have to be unmarried at the time you apply for ex-spouse retirement benefits—there’s no rule against remarrying after you qualify for those benefits.

EXAMPLE 17

You and your husband are both 60, and he plans to work until he’s at least 65. You never worked, so you will get no Social Security retirement on your own. And since your husband will continue working until he reaches age 65, you won’t be able to get any spouse retirement benefits on his record until then. Divorcing him might be financially beneficial.

Two years after you divorce, you are both 62 and eligible for Social Security retirement benefits. You can now qualify for divorced spouse retirement benefits. Since your ex-husband’s full age 65 retirement benefit is $1,100/month, your monthly ex-spouse benefit becomes $412.50—that’s $412.50 more than you would receive without the divorce! Because you are divorced, your ex-husband’s continued earnings don’t reduce your benefits. Had you stayed married, you would have received flowers on your anniversary but nothing from Uncle Sam.

Don’t get so excited by the idea of cashing in on your ex-spouse’s record that you forget your own earnings record, however. If your own full retirement benefit is half (or more than half) of your ex-spouse’s full retirement benefit, then you will be better off on your own record. (See here.)

GEM: Delaying a Divorce May Also Add to Income

As we’ve explained, getting a divorce can add glitter to your golden years. But in some cases, delaying a divorce is wise. See Example 18.

EXAMPLE 18

You were remarried at age 50, after your first husband died. Almost 10 years later, things just weren’t working and so you got divorced. Now you are 65 and looking to Social Security for benefits. Your ex-husband worked all his life and has a nice full age 65 retirement benefit of $1,000/month. Can you cash in and collect monthly divorced spouse retirement payments of $500?

The answer is no! You were only married a little over nine years to him, so you don’t qualify. Instead, you’re stuck with a much lower amount based on your own or your late husband’s work record.

If you had delayed the divorce just a few more months, you could have qualified for divorced spouse retirement benefits. Because you didn’t know the Social Security retirement rules, you lost out on thousands of dollars that could have been yours for the rest of your life. So, if you’ve made it through almost 10 years of marriage, try to stick it out just a little longer. Uncle Sam will reward your tenacity.

* * *

Children’s and Grandchildren’s Benefits

Children of older Americans are rarely eligible for retirement benefits on a parent’s work record, since eligibility requires a child (including an adopted child or stepchild) to be unmarried and either:

• Under age 18 (19 if still in high school)

• Any age if disabled before age 22 (and still disabled)

The same requirements apply to grandchildren, but they must also be dependent on the grandparents, and their parents must be deceased or disabled.

Each eligible child or grandchild is entitled to 50% of the parent’s or grandparent’s full retirement benefit while alive (75% after he/she dies).

Maximum Family Benefits (MFB)

Assorted family members may collect Social Security retirement benefits based on one worker’s earnings record. These lucky folks are listed here. The total amount of all retirement benefits can go beyond the worker’s full age 65 retirement benefits, but there are limits. Family members collecting benefits based on a worker’s benefits cannot exceed limits by the MFB. The only exception is a divorced spouse: his or her benefits are completely independent of the MFB, whether the worker is alive or dead. Table 1.9 shows the MFB limits, and Appendix 4 explains how the MFB is calculated.

TABLE 1.9

Limits on Family Benefits

Worker’s Full Age 65 Retirement Benefit |

|

MFB |

|

||

$ 300 |

|

$ 450 |

400 |

|

600 |

500 |

|

756 |

600 |

|

1,028 |

700 |

|

1,300 |

800 |

|

1,453 |

900 |

|

1,587 |

1,000 |

|

1,750 |

The MFB is the most the family can receive based on the worker’s earnings. The worker’s retirement benefit is first subtracted from the MFB; it is not reduced. Then the remaining family members’ benefits are reduced proportionately to bring total benefits down to the MFB limit.

GEM: A Divorce May Be Good for the Family

We’ve already explained how the Government encourages divorces. Well, here we go again: MFB = Means Family Break-ups. Compare Examples 19 and 20.

EXAMPLE 19

Your full age 65 retirement benefit is $900/month. At 62, you start receiving checks of $720/month. Other members of your family can also cash in. Your wife is 52 and is caring for your disabled child, so they each are entitled to $450/month (50% of your full benefit). Total family benefits are $1,620/month ($720 + $450 + $450).

But your family can’t collect $1,620/month. The Maximum Family Benefit is $1,587/month—see Table 1.9. Your wife and child together lose $33/month ($1,620 – $1,587).

EXAMPLE 20

Take the same facts as in Example 19, except you and your wife get divorced. You remain entitled to $720/month, and your ex-wife and child each remain entitled to $450/month. But now your ex-spouse’s benefits don’t count in the Maximum Family Benefit. The three of you can collect the full $1,620/month—a raise of $396 each and every year!

The politicians who write the Social Security laws are saying that, if you’re smart, you’ll divorce and live together. Staying married becomes a liability. Isn’t that sad?

* * *

THE GOVERNMENT’S SECRET TAX ON SOCIAL SECURITY BENEFITS

What Uncle Sam giveth, he can taketh away. Since 1984, the Government has been taxing the Social Security retirement benefits of many older Americans. Why would the same Government that provides these benefits with one hand take them back with the other? Only your congressman knows for sure!

Benefits are taxed as income, supposedly at the standard income tax rates of 15 and 28 percent. But in fact, the tax on retirement benefits can secretly push your income tax rate well above the published brackets. Even though you may think you’re in the 15 percent tax bracket, the hidden tax on Social Security benefits can push your actual tax rate much higher.

Let us tell you how the Secret Social Security tax trap works and, more important, how you can avoid a secret tax trap that unfairly burdens older Americans. The first step is to figure what portion of your Social Security retirement benefits will be taxed. Uncle Sam has decided that you have to pay tax on as much as half of your Social Security retirement benefits if your income exceeds the limits in Table 1.10.

TABLE 1.10

You Must Pay Tax on Social Security Benefits If Your Income* Goes Above:

• $25,000 if you are single

• $25,000 if you are married filing separate returns, and you did not live with your spouse at any time during the year

• $32,000 if you are married and file a joint return (you and your spouse must combine your incomes, even if your spouse didn’t receive any benefits)

• $0 if you are married filing separate returns, and you lived with your spouse at any time during the year

* Income includes (1) half your annual Social Security benefits (before any deductions for Medicare Part B premiums), and (2) all your other income (including your pension, wages, dividends, interest—even tax-exempt interest, such as from mutual funds or bonds). From this, you can subtract the amount of any IRA deduction you are entitled to take and alimony you paid.

If your income is above the Social Security limits in Table 1.10, you can expect to pay tax on whichever is less:

• Half your Social Security retirement benefits (subtracting any repayment of overpaid benefits, but adding any workers’ compensation benefits)

• Half the amount by which your income exceeds the applicable limit

Table 1.11 demonstrates how to calculate the taxable portion of your benefits.

TABLE 1.11

1. Your (and your spouse’s, if applicable) annual Social Security benefits are $_________.

2. Half of line 1 is $________.

3. Your (and your spouse’s) additional income for the year, taxable and nontaxable, is $_________.

4. Adding lines 2 and 3 equals $_______.

5. The applicable limit from Table 1.10 is $_________.

6. Subtracting line 5 from line 4 equals $___________. (Do not enter less than $0.)

7. Half of line 6 equals $_________.

8. The lesser of lines 2 and 7 is $__________, your taxable benefits.

Example 21 shows how you use Table 1.11 to calculate the amount of benefits that are taxable.

EXAMPLE 21

You are widowed, and your Social Security benefits are $600/month ($7,200/year). You also receive a private pension of $400/month ($4,800/year). Your interest and dividends total $24,000/year.

1. Social Security benefits are $7,200.

2. Half of your benefits is $3,600.

3. Your additional income is $28,800.

4. Adding $3,600 and $28,800 equals $32,400.

5. The applicable limit from Table 1.10 is $25,000.

6. Subtracting $25,000 from $32,400 equals $7,400.

7. Half of $7,400 is $3,700.

8. The lesser of line 2 and 7 is $3,600, your taxable benefits.

Therefore, fully half of your Social Security retirement benefits are taxable.

How much does the taxation of benefits really cost you? Much too much! See the sinister effect of the secret tax trap by comparing Examples 22 and 23.

EXAMPLE 22

You are married (filing a joint return), and you and your spouse annually receive Social Security benefits of $10,000, pensions of $15,000, and interest and dividends of $16,000. First, figure how much of your Social Security benefits are taxable, using Table 1.11.

1. Social Security benefits are $10,000.

2. Half the benefits is $5,000.

3. Your and your spouse’s additional income (pension, interest and dividends) is $31,000.

4. Adding lines 2 and 3 equals $36,000.

5. The applicable limit from Table 1.10 is $32,000.

6. Subtracting lines 5 from 4 equals $4,000.

7. Half of line 6 is $2,000.

8. The lesser of lines 2 and 7 is $2,000.

The taxable portion of your and your spouse’s Social Security benefits is $2,000.

Now, let’s calculate your income tax. First, take all taxable income together: $15,000 (pension), $16,000 (interest and dividends), and $2,000 (Social Security)—that equals $33,000. Then subtract the standard deduction, which we’ll say is $7,400 ($6,000 basic deduction plus $700 for each of you since you’re both 65 or older) and personal exemptions of $4,600 ($2,300 for each of you), which leaves you with net taxable income of $21,000 ($33,000 – $7,400 – $4,600). The tax you pay on $21,000 is $3,150.

EXAMPLE 23

Now we’ll change Example 22 just slightly, adding $5,000 more in interest income. In the 15 percent bracket, you should expect to pay $750 in taxes on the added income. But because of the Government’s secret tax trap, you’ll pay a lot more.

Let’s first calculate taxable benefits:

1. Social Security benefits are $10,000.

2. Half the benefits is $5,000.

3. Additional income is $36,000.

4. Adding lines 2 and 3 equals $41,000.

5. The applicable limit from Table 1.10 is $32,000.

6. Subtracting line 5 from line 4 equals $9,000.

7. Half of line 6 is $4,500.

8. The lesser of lines 2 and 7 is $4,500.

By adding $5,000 of interest, your Social Security taxable benefits increase by $2,500. Now let’s recalculate the tax. Adding all your taxable income gives you $40,500 ($15,000 pension, $21,000 interest and dividends, and $4,500 Social Security). Subtracting the same deductions and exemptions leaves you net a total taxable income of $28,500 ($40,500 – $7,400 – $4,600). In other words, by increasing interest and income by $5,000, you add $7,500 of taxable income. The tax you pay is $4,275, an increase of $1,125.

Okay, what’s all this mean? It means you’re paying a lot of tax on your income—more than the Government is telling you. Although at your income level you are supposedly in the 15 percent bracket, you actually pay 22½ percent on the additional $5,000 of income—7½% more than the highest published rate. The Government says you’re paying 15 percent tax, when the real tax is 50 percent higher! Talk about taxation without truthful representation! That’s the Secret Social Security tax trap that’s hurting older Americans.

GEM: Sidestep the Secret Tax Trap with Tax-free Investments

If you can avoid the hidden tax trap, you will save yourself money that can surely be put to better use than paying off the federal deficit. Tax-free investments such as municipal bonds may do the trick. See Example 24.

EXAMPLE 24

Let’s change Example 23 a little. Instead of putting all your funds into taxable investments, suppose you put a portion into tax-free instruments. The $5,000 of added income that we included in Example 23 is now tax-free rather than taxable. Watch what happens:

Your taxable Social Security benefits remain exactly the same—$4,500. But your net total taxable income is reduced by the $5,000 of tax-free income. The tax you pay is $3,525—$750 less than the tax you paid in Example 23, when the $5,000 income was taxable.

Even tax-free investments don’t completely avoid the Government’s secret tax trap. In this example you still wind up paying about 7½ percent on the $5,000 investment income which is supposedly “tax free.” But that’s a lot better than paying 22½ percent on the same taxable income, right?

Tax-free investments often don’t pay as much interest as do taxable investments, and you must examine the actual impact different investments will have on your bottom line. But tax-free investments, even with lower returns, may put more money in your pocket because you’re avoiding the Government’s secret tax trap, as Example 25 shows.

EXAMPLE 25

Let’s go back to Example 23 once more. Remember, that’s the situation where you made investments yielding $5,000 of taxable income. If the principal invested was $55,500, and the rate of return was 9 percent, that would yield $5,000 taxable income. In Example 23, your net after-tax income was $41,725 ($46,000 – $4,275 tax). Now take the same $55,000 and invest it in tax-free bonds, which yield $4,400—$560 less than the $5,000 from taxable investments. How can you be better off? Take a look:

First, figure your taxable Social Security benefits:

1. Social Security benefits are $10,000.

2. Half of line 1 is $5,000.

3. Additional income is $35,440.

4. Adding lines 2 and 3 equals $40,440.

5. The limit from Table 1.10 is $32,000.

6. Subtracting line 5 from line 4 equals $8,440.

7. Half of line 6 is $4,220.

8. The lesser of line 2 and 7 is $4,220.

Adding all your taxable income gives you $35,220 ($15,000 pension, $16,000 interest and dividends, and $4,220 Social Security); subtracting the same deductions and exemptions as in Example 23 gives you a net taxable income of $23,220. The tax on that amount is $3,483.

Your net after-tax income is $41,957 ($45,440 – $3,483). Although the tax-free investments earned you $560 less, you wind up with $232 more in your pocket ($41,957 – $41,725, which was your net after-tax income in Example 23). The extra benefit comes from beating the secret Social Security tax trap.

GEM: Stagger or Defer Income to Avoid the Secret Social Security Tax Trap

Deferring or staggering your income is another way to cut the hidden tax on your Social Security retirement benefits. Compare Examples 26 and 27 to see how this can have a staggering effect on your income:

EXAMPLE 26

You are a widow, your annual Social Security retirement benefits are $8,500, and your pension pays $25,000 per year. In addition, you have 12-month Treasury Bills (or CDs or other investments) yielding $5,000 income per year.

Your taxable Social Security benefits, using Table 1.10, are $4,250:

1. Social Security is $8,500.

2. Half of line 1 is $4,250.

3. Additional income is $30,000.

4. Adding lines 2 and 3 equals $34,250.

5. The applicable limit is $25,000.

6. Subtracting line 5 from line 4 equals $9,250.

7. Half of line 6 equals $4,625.

8. The lesser of lines 2 and 7 is $4,250.

All taxable income is $34,250 ($25,000 pension, $5,000 interest, plus $4,250 taxable Social Security). Now subtract the standard deduction ($4,300) and the personal exemption ($2,300); this gives you a net taxable income of $27,650. The income tax to be paid on that amount is $4,954 (using the IRS tax tables).

EXAMPLE 27

Let’s change Example 26 just a little. Instead of collecting $5,000 interest each year, suppose you collect $10,000 every other year. One way this can be done is by purchasing two-year Treasury Notes (instead of one-year Treasury Bills).

In the year the Treasury Notes come due, your taxable benefits remain at $4,250:

1. Social Security is $8,500.

2. Half of line 1 is $4,250.

3. Additional income is $35,000.

4. Adding lines 2 and 3 equals $39,250.

5. The applicable limit is $25,000.

6. Subtracting line 5 from line 4 equals $14,250.

7. Half of line 6 equals $7,125.

8. The lesser of lines 2 and 7 is $4,250.

Taxable income goes up to $39,250, less the same standard deduction and exemption. You end up with a net taxable income of $32,650. The income tax you pay on that amount is $6,354 (using IRS tax tables).

In the off-year, when the notes don’t come due, your taxable benefits drop to $2,125:

1. Social Security is $8,500.

2. Half of line 1 is $4,250.

3. Additional income is $25,000.

4. Adding lines 2 and 3 equals $29,250.

5. The applicable limit is $25,000.

6. Subtracting line 5 from line 4 equals $4,250.

7. Half of line 6 equals $2,125.

8. The lesser of lines 2 and 7 is $2,125.

Taxable income drops to $27,125, less the same deduction and exemption, for a net taxable income of $20,525. The tax on that amount is $3,079.

So what have you accomplished? Had you gone along as you were in Example 26, the tax you would have paid over two years would have been $9,908 ($4,954 each year). But by deferring income as in Example 27, you pay tax of only $9,433 over the two years ($6,354 and $3,079). That’s a tax savings of $475! And it cost you nothing (except the cost of this book). You receive the same total income (maybe even a little more by purchasing longer-term notes instead of one-year instruments), and you pay much less tax.

As you can see, staggering or deferring income can reduce the secret Social Security tax bite. Example 27 showed one way to stagger or defer income, but there are many other ways to accomplish the same thing. Investing in EE bonds or single premium deferred annuities and stretching out withdrawals from IRAs are three other methods. Talk to your financial advisor about how to avoid the secret Social Security tax trap—you’ll be putting more dollars into your own pocket!

WORKING TO SUPPLEMENT BENEFITS

You’re 65 and you’d like to supplement your income from your Social Security, pension, and investments. Does it pay to work? For Uncle Sam, the answer is clearly yes. Uncle Sam may easily get more from your efforts than you do!

Triple Working Whammy

Our elected officials have put a triple whammy on working to supplement Social Security retirement: (1) they reduce your benefits; (2) they tax your benefits; and, to make sure they’ve gotten you, (3) they tax (twice) your supplemental income. This triple whammy, described in Table 1.12, can cost you 50 cents of every dollar you earn!

TABLE 1.12

Triple Working Whammy

Whammy One: Reduction in Benefits

You may earn up to $10,200 (in 1992) if you are between 65 and 69 years old, and still receive all your Social Security benefits; if you are 62 to 65, you may earn $7,440 without losing any benefits. But if you earn more than the allowed amounts, your Social Security benefits (your own retirement, spouse retirement or survivor benefits) will be reduced: $1 for every $3 over the limits, for workers 65–69; $1 for every $2 over the limits for workers under 65. For example, if you are 63 and earn $9,440, you’ll lose $1,000 in benefits (because you earned $2,000 over the $7,440 limit). Once you reach age 70, you can earn any amount without losing benefits.

Whammy Two: Taxation of Benefits

Your added income may make your Social Security benefits taxable by boosting your income over the limits in Table 1.10. This penalty applies at any age—even after you reach age 70.

Whammy Three: Taxation of Income

You pay both income tax and Social Security (FICA) tax on your added income, as is true at any age.

GEM: Watch Out for the Triple Working Whammy!

A job that pays $10 an hour may sound pretty good, but would you still be interested if you actually take home less than $5 an hour? Well, that’s exactly the potential impact of the Triple Working Whammy. Before interrupting the serenity of retirement by getting a job, make sure you understand how much you’ll actually be increasing your spending power. You may change your mind. Consider Example 28.

EXAMPLE 28

You and your spouse are 65. Together you receive $13,000 in Social Security benefits, $10,000 in pension benefits, and $15,000 in interest and dividends. Plugging into Table 1.11, you find that none of your Social Security benefits are taxable:

1. Social Security benefits are $13,000.

2. Half of line 1 is $6,500.

3. Your combined additional income is $25,000.

4. Adding lines 2 and 3 equals $31,500.

5. The applicable limit from Table 1.10 is $32,000.

6. Since total income in line 4 is less than the limit in line 5, no benefits are taxable.

Since no Social Security benefits are taxable, your taxable income is $25,000 (pension, interest, and dividends). Subtracting your deductions and exemptions of $12,000 gives you a net taxable income of $13,000. The income tax is $1,950, which is less than 8 percent of your taxable income and only 5 percent of your total income. Your real, spendable, after-tax income is $36,050.

Now $36,050 isn’t bad, but you’d like to supplement that amount by working. You take a job paying about $2,000/month—not a fortune, but enough to make a difference. How much of that added money do you think you’ll get to keep? Since the top tax bracket is 31 percent, you surely will get to keep at least 69 percent of your added income, right? Wrong!

First, let’s figure the amount of your Social Security benefits that you get to keep. Say your job earnings are $25,200. That’s $15,000 over the limit of $10,200 which you may earn and retain all your benefits. You lose $1 for every $3 earned over the limit, so $15,000 “excess” earnings will cost you $5,000 in benefits. That’s Working Whammy No. 1.

Second, your taxable Social Security benefits are now $4,000:

1. Social Security benefits are $8,000 (remember, your benefits are reduced owing to earnings).

2. Half of line 1 is $4,000.

3. Your combined additional income is $50,200 (pension, interest, dividends, and wages).

4. Adding lines 2 and 3 equals $54,200.

5. The applicable limit from Table 1.10 is $32,000.

6. Subtracting line 5 from line 4 equals $22,200.

7. Half of line 6 equals $11,100.

8. The lesser of lines 2 and 7 is $4,000.

Your taxable Social Security benefits went from $0 to $4,000—that’s Working Whammy No. 2.

Working Whammy No. 3 is the added income tax and Social Security tax on the earnings. First let’s figure the income tax. Taxable income is $54,200 (including $4,000 of benefits). Assuming the same deductions and exemptions, net taxable income is $41,720. The income tax on that amount is $7,028. Social Security (FICA) tax is paid only on the earnings. The tax is 7.65 percent of $25,200, or $1,928. So total tax (income and Social Security) is $8,956.

Ready to see the combined effect of the Triple Working Whammy? Although you earned an additional $25,200, you paid an additional $7,006 in taxes, plus you lost $5,000 in Social Security benefits, leaving you with a gain of just $13,194. In other words, the effective “tax” on the added income was not 15 percent, or even 28 percent—the tax was 48 percent! Uncle Sam received almost as much of your additional earnings as you did (and we haven’t even figured in state and local income taxes on the earnings yet). Not exactly what we call a work incentive!

Retirement-Year Loopholes to Minimize the Triple Working Whammy

We have already explained that, after you retire, annual earnings over the limits ($10,200 if 65–69; $7,440 if 62–65) will reduce your benefits. But two special rules apply for the year in which you retire:

• Retirement year loophole 1: Earnings during the part of the year before retirement do not count against you.

• Retirement year loophole 2: For each month after retirement that you do not earn 1⁄12 of the applicable limit ($850 a month if 65–69; $620 a month if 62–65), you will not lose any benefits.

The following examples show how these retirement year loopholes work.

EXAMPLE 29

Suppose during the first three months of 1992 you were still working. Your earnings were $6,400/month, for a total of $19,200. Starting in April, you retired (at 65) and started taking Social Security benefits of $700/month. For the year of 1992, you had earnings of $19,200 and Social Security benefits of $6,300.

Your $19,200 of earnings exceeded the $10,200 limit by $9,000. Under the normal retirement rules, you’d lose $3,000 of benefits ($1 for every $3 over the limit). But the retirement-year loophole—for your retirement year only—allows you to keep all your Social Security benefits, without any reduction. Earnings during the part of the year before you retired don’t count against you.

EXAMPLE 30

Let’s take the same facts as in Example 29, except that you continued working part time after you retired. For each month, April through December, you earned $700/month to supplement your benefits.

You still don’t lose a penny of your retirement checks. For each month that you earned less than $850 (if 65–69), you receive all your Social Security retirement benefits too.

GEM: Don’t Lose Benefits Because of Income Earned Before Retirement but Received After

Earnings before retirement don’t count against you in your retirement year, even if you don’t receive the income until later.

EXAMPLE 31

Let’s go back to Example 29. You are a gardener-landscaper, and you earned $19,200 during the first three months of 1992. Starting on April 1, you retired. As we all know, people don’t pay their bills the moment they get them. So let’s say $12,000 of the $19,200 didn’t come in until the months after you retired. Does that money reduce your Social Security retirement benefits?

No! Not if you make sure the Government understands that the money was earned before you retired. That way, you get to keep all of your benefits.

GEM: Shift Income to Take Advantage of the Retirement Year Loophole

In some jobs, particularly if you are self-employed, you may have the ability to control the timing of income. By moving income into the months before retirement, and by carefully shifting around income during the months after retirement, you can save yourself hundreds—maybe thousands—of dollars during your first retirement year. See Examples 32 and 33.

EXAMPLE 32

You have operated your own gardening business for many years. On March 31, when you turn 65, you plan to retire and start taking Social Security retirement benefits. You’ll still continue to take some gardening jobs, but you’ll be cutting way back.

Get as much of the income as you can before you officially retire. For example, if you’ve already got some jobs under way in March, bill in March; don’t wait to bill until the job is done in May or June. Why?

The Government usually counts income as earnings in the month you receive it. Now, we did say that money earned before you retired, but received after, shouldn’t reduce your retirement benefits. But if you’re still working after retirement, it may be hard to prove how much of your income was actually earned before retirement. Reduce your headaches by shifting as much income into preretirement months as possible.

EXAMPLE 33

Let’s continue with the facts of Example 32. After you retire on March 31, you are due to receive monthly Social Security retirement payments of $600. To supplement your income, and to keep busy, you continue to work your gardening business part time. Your income comes in at $900/ month. Unfortunately, since that’s over the earnings limit, your income each month will reduce your benefits. Depending on how much you earned from January through March before retirement, you might lose all $5,400 of your benefits ($600/month for nine months).

But let’s say you can slide income around a little. Instead of getting $900 income every month, you take in $1,800 every other month. During the four or five months in which you received no income, your benefits are protected. In other words, by carefully shifting income during your retirement year, you are able to save $2,000 to $3,000 in benefits (four or five months at $600 a month)!

* * *

70th Year Loophole to Minimize the Triple Working Whammy

Earnings after you reach age 70 will not reduce your Social Security retirement benefits. That opens up another Golden Opportunity to increase income.

GEM: During Your 70th Year, Postpone Income

Example 32 shows how you can benefit by moving income up into the months before you retire. During the year you reach age 70, do the reverse—postpone income until after your birth date. That should allow you to avoid a reduction of benefits for the portion of the year before you reach 70. Have a happy 70th birthday—thanks to Uncle Sam!

* * *

INVESTMENTS TO SUPPLEMENT BENEFITS

Uncle Sam must work part time on Wall Street because, while he discourages work after retirement by penalizing earnings with a triple whammy, he encourages investments by treating them more favorably. Investment returns, no matter how large, will not trigger Whammy No. 1, a reduction in Social Security benefits. Table 1.13 lists the do’s and don’ts of income calculations. When you calculate your income to see if any of your Social Security retirement benefits must be reduced, make sure you include only income that counts.

GEM: Change Salary into Dividends

Investment income avoids the reduction in Social Security benefits based on earnings from work. For older Americans who are self-employed, changing salary into dividends can be an “interesting” way to save money. Examples 34 and 35 show how.

TABLE 1.13

Income That Reduces Social Security Benefits

When calculating your income to decide whether any of your Social Security benefits will be reduced:

Do Count

• Salary and wages

• Earnings from self-employment (net of business costs)

• Bonuses and commissions

Do Not Count

• Interest from CDs, bank accounts, etc.

• Dividends

• Pensions

• Income from IRAs and other retirement funds

• Inheritance

• Payments from certain trust funds or annuities that are exempt from income tax, such as profit-sharing

• Capital gains

• Rental income

• Damages (other than back wages) awarded in a court judgment

• Contest winnings

• Tips under $20 a month or not paid in cash

• Sick pay, if received more than six months after you last worked

• Worker’s and Unemployment Compensation benefits

• Reimbursements or allowances for travel or money expenses to the extent not counted as wages by the IRS

• Self-employment earnings from work performed before you retired

EXAMPLE 34

You own your own small business, which you have been running for a number of years. You’ve been drawing a decent salary for your efforts and pouring the rest of the profits back into the business. Now that you and your spouse have reached 65, you are ready to retire. Your daughter will continue to run the business, and she’ll continue to pay you a $24,000-a-year salary. How do you come out?

Not very well! Assuming the same facts as in Example 28 (Social Security benefits of $13,000, and $50,200 in other income, including the $25,200 of income from the business), you are left with approximately half of the $25,200 salary thanks to the Triple Working Whammy. Uncle Sam gets the rest. But if you take the $25,200 as dividends on your ownership of the company, rather than as salary, you are far better off, as Example 35 shows.