seven the first

energy technology

Doom Avoided

“The battle to feed humanity is over. In the 1970s the world will undergo famines—hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date, nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.”1

With those words, biologist Paul Ehrlich opened his 1968 best seller The Population Bomb. Alarmed by the incredible growth of human population in the twentieth century, Ehrlich predicted that food supplies could not keep up.

Others did as well. A month before The Population Bomb came out, the even more alarming Famine—1975! by agronomist William Paddock and diplomat Paul Paddock hit the shelves. Like The Population Bomb, the Paddocks’ Famine—1975! forecast widespread starvation and mass death as humanity found itself unable to grow enough food to keep up with a surging population. And like The Population Bomb, Famine—1975! became a best seller.

Four years later, the Club of Rome published The Limits to Growth which even more broadly forecast that a massively expanding population was on the brink of exceeding the amount of food that could be grown, the amount of oil that could be extracted, the amount of metals that could be mined, the amount of wood that could be harvested from forests, and the amount of pollution that the environment could absorb. The computer models the book was based on forecast widespread collapse—fueled by surging population, overconsumption, and over-pollution—early in the twenty first century.

The authors of these books had reasons to be concerned. In 1800 there were 1 billion people on Earth. In 1900, that number had expanded to 1.6 billion. By 1965, there were 3.3 billion people on the planet. Population was rising, and the rise was accelerating.2

In 1965, agriculture already covered one-third of the Earth’s land surface. Much of the rest was covered with cities or precious and vital forests, or it was desert, mountain, marsh, or otherwise not useful for agriculture. There was very little land left to expand into. In comparison, population was set to soar over the century by 300 percent. In the absence of rapid and strict population control, humanity was poised to far outstrip its ability to generate its most essential resource, food. The logic was difficult to argue with.

It was also wrong. The famines that Ehrlich and the Paddocks projected didn’t occur. The massive collapse of the ecology and human industrial civilization that The Limits to Growth predicted isn’t on schedule. In the 1970s, the fraction of the world suffering malnutrition and starvation dropped.3 The number of calories in the world food supply rose faster than the population did. The world didn’t run out of oil, or steel, or other essential resources. Industrial society didn’t collapse.

Perhaps the best known of all “limits to growth” predictions are those of Thomas Malthus. In his 1798 book, An Essay on the Principles of Population, he reasoned that populations grow exponentially, increasing by a certain percentage each year, while food production grows only arithmetically, growing by a fixed amount. Each year, the population would grow by a larger absolute number than the year before, while the food supply would increase by a fixed and ever-more-insufficient amount. Thus, he reasoned, population growth would outstrip our ability to grow food. Massive famines and death would result in the early 1800s.

Malthus proved to be wrong. Quite wrong, in fact. Since the publication of his book, worldwide life expectancy has gone from just over thirty years to today’s sixty-nine years. Life expectancy in England, where he wrote, is approaching eighty years. Food production hasn’t grown arithmetically after all—it’s grown exponentially, staying consistently ahead of population growth, which has in turn slowed down.

I highlight these past incorrect predictions of doom not because I want to instill any complacency in you. Just because we’ve heard false cries of “wolf!” in the past doesn’t assure us that there aren’t wolves at the door today. The threats to our civilization and our planet are real. We have to address them. We need not fall into despair at their size, but we can’t afford to ignore them, either.

I highlight these past incorrect predictions for a slightly different reason. It’s not that they were all wrong. It’s that they were all wrong in the same way, and for the same reason. They all ignored or underestimated the most critical human faculty that exists, and the most important source of our prosperity.

Malthus, Ehrlich, and the Club of Rome all dramatically underestimated the extent to which human ingenuity could lift the production of food. They made the mistake of looking at the physical resource—land—as the most important determiner of future output. They assumed that the invisible resource—our knowledge of how to maximize yields from that land—would have only a small effect on overall productivity. The Club of Rome’s predictions about energy and natural resources in The Limits to Growth made a similar mistake.

What we’ve seen is that the opposite is true. The physical resources matter. But the change in our knowledge resources—our science, our technology, our continual generation of new useful ideas—has made far more impact over the course of history. Knowledge acts as a multiplier of physical resources, allowing us to extract more value (whether it be food, steel, living space, health, longevity, or something else) from the same physical resource (land, energy, materials, etc.).

That’s what has driven human history. And the continuation, willful direction, and acceleration of global innovation is our best hope of overcoming peak oil, climate change, and the whole panoply of resource limitations and environmental risks that we face.

Sibudu Cave

On the eastern coast of South Africa, in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, home of the Zulu Kingdom, twenty-five miles north of Durban and nine miles in from the coast, lies Sibudu Cave, one of the richest archeological sites in the world for early human tools. Sibudu is nearly 200 feet long and 60 feet wide, a natural cavity set in one of the steep limestone cliffs that dot the area. Today from the cliff face you can look west and south over the vast sugarcane plantation that stretches around it. Tens of thousands of years ago, the area was likely jungle. At least six times over the past 70,000 years, bands of humans made this cave their home, sometimes passing it on from generation to generation for hundreds of years at a time. In doing so, they left us ample evidence as to who they were and the lives they lived.4

Although Sibudu was first discovered in 1929, archeologists didn’t explore it until 1983. The cave was then virtually ignored until 1998, when researchers from the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg returned and began regular excavations. In 2010 a team from the university found stone points dating back to 64,000 years ago. The points are smaller than spearheads, small enough and light enough to have been propelled long distances at lethal velocities. Their forward edges have microscopic deposits of bone and blood. Their sides and back edges bear deposits of a crude glue made by combining plant gum and red ochre. These stone points are arrowheads, the oldest ever found.

We are the invention species. Our ancient ancestors learned to use and create fire. They learned to create choppers and axes. They learned to fashion spears and bows. And in all of those ways, they increased the value of inert matter by infusing it with their ideas.

The bow and arrow, for example, allowed humans to do more with less. By killing from a distance, hunters could kill game that might otherwise be beyond their abilities to bring down safely. The speed of an arrow allowed hunters to kill from a stationary position rather than chasing or charging animals with spears. The bow brought in more meat with less risk, more calories with fewer expended. It increased the efficiency with which humans could gather the energy most vital to their survival.

A bow and arrow is a powerful tool made from crude, abundant, mundane materials. The parts are small rocks, red ochre, plant gum, green wood (for the bow staff and the arrow shafts), and rawhide or sinew (for the bowstring). All of those were plentiful for our Stone Age ancestors. In economic terms the individual pieces were cheap. Even the labor to make the bow and arrows was relatively short, comprising perhaps several hours of work over the course of a few days.

The real value in the bow and arrow is in its design. Its utility comes not primarily from its parts (which are abundant), not primarily from the labor to construct it (which is minor compared to a bow’s benefits), but from the precise way in which those pieces fit together and work together to create something greater than the sum of their parts. The key ingredient that adds the value to the pieces and the labor is the human knowledge. That knowledge transforms the inert matter into a powerful tool.

And that knowledge spreads. The first bow was copied millions of times, and improved upon along the way. The value of a single bow is significant. The value of the idea of the bow is tremendously greater.

Knowledge, in the language of economists, is non-rival. Rival goods can only be used by one person, or a set number of people, at a given time. A non-rival good is something of value that any number of people can enjoy the benefits of. It is, in another way of thinking, non-zero-sum. In a zero-sum system, one person’s gain is another’s loss. In a non-zero-sum system, both parties can benefit. The possibility of sharing ideas makes human interactions non-zero. It allows the total size of the pie to grow.

Only information works this way. Everything else in nature is diluted or depleted by increased use. A piece of food does not become more valuable if shared by a hundred people—it just gets divided among them. A bow itself can only be used by one hunter at a time, and eventually it will break. But the design for a bow can be used again and again. It’s software, not hardware.

Knowledge, information, is fundamentally different from physical resources. The more people who make use of a piece of knowledge, the more total impact it has on the world. It not only adds more value to everything it touches, it does so a potentially infinite number of times.

The key turning point in human evolution was our ability to tap into this non-rival, non-zero-sum resource. The day we achieved the ability to create sophisticated ideas, and to communicate them clearly to one another, our universe changed. We were no longer bound by the same constraints of population, food, and scarce resources that we and all other creatures on Earth always had been. We had tapped into a new and potentially infinite resource. Nothing has been the same since. Nothing ever will be again.

The First Energy Technology: Agriculture

The innovations of early humans centered on the acquisition of the energy source that all human life depends on: food. Without adequate food, human civilizations can’t survive. They can’t maintain their populations. Hunger and then starvation set in. Famine kills off surplus population. Warfare may arise as people turn violent to fight over the last scraps. Order and structure in society break down.

Over the last 12,000 years, human population has increased from roughly five million men and women to seven billion, a factor of more than 1,000. At every step of the way, that’s only been possible because we’ve found ways to acquire more food.

Most of that gain has had little to do with increasing the amount of land we acquire the food from. By 10,000 BC, humans had already spread to most of the habitable corners of the planet and were ranging over most of that territory hunting, fishing, and foraging. The more than 1,000-fold increase in human population and human food supply hasn’t come from more land. It’s come from increasing the efficiency with which we acquire food from the land.

Food, in essence, is concentrated solar energy. Plants turn the energy of the sun, plus generally abundant water, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen, into carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. Animals consume that energy, and use some of it to build muscle and fat. When you bite into an apple, a piece of bread, or a steak, what you’re consuming is stored-up solar energy.

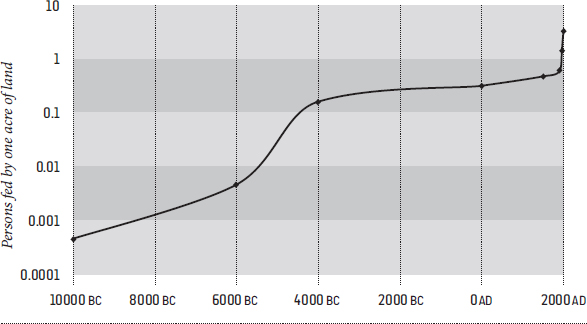

The story of humanity is one of becoming more and more adept at harvesting that solar energy—turning more of the energy that hits the ground into food. As hunter gatherers, it took an average of almost three thousand acres to feed one person. Today it takes around a third of an acre.5

That roughly 10,000-fold increase in the amount of solar energy we capture per acre has come from a steady stream of innovations. First, agriculture itself—the idea that we could intentionally plant seeds of plants that were good to eat, and harvest them later. Almost overnight, that increased the amount of food our ancestors could grow by at least a factor of 10, and in some cases a factor of 100. Following the basic idea of agriculture came a host of improvements. Irrigation, hoes and digging sticks, harnessing oxen to pull plows.

Even in the periods of history we consider the darkest and most devoid of progress, agricultural innovation continued. The Western Roman Empire fell apart in the fifth century AD. Yet in the sixth century agricultural productivity in Europe improved as farmers learned to use the breast strap to harness horses, which can plow more land per day than oxen. The ninth century saw more improvements as the horse collar was introduced, letting horses put their full strength into plowing. The tenth century, still firmly in the so called “Dark Ages,” saw the introduction of the medieval moldboard plow, which turned over the earth to aerate it, creating furrows alternated with rows of tall soil, leaving natural channels for water to flow through, and further boosting yields.

The eleventh and twelfth centuries saw the advent of three-field crop rotation, where farmers learned to plant legumes such as peas and beans to simultaneously grow food and inject much-needed nitrogen (which legumes can absorb from the air, but grains cannot) back into the soil.

Other agricultural innovations followed—the seed drill, four-field crop rotation, horse shoes, improvements to plows and scythes, and more. In parallel, farmers continued to pick seeds from the best crops to plant for the next year, and to domesticate more plants and animals for human use. In all, those agricultural innovations boosted yield by a factor of 10 between the first generation of farming and the dawn of the Renaissance. At the end of the so-called dark ages, farms produced twice as much food per acre as they had at the height of the Roman Empire.

There’s a saying that “you can’t eat information.” That may be so, but the food we eat today is the fruit of thousands of years of increasingly high-quality information—the knowledge of how to farm—what seeds, what tools and how to use them, what times of year, what irrigation, what sequence of one crop after another on the same land. What we eat is solar energy, filtered, concentrated, and distilled through the lens of human knowledge. The energy the Earth receives from the sun each year has remained more or less constant through all of human civilization. What’s allowed us to flourish is our increasingly sophisticated knowledge of how to capture an ever-growing but still tiny fraction of that energy in a form that can fuel our bodies. Every step in the advancement of our knowledge has brought with it an increase in the amount of energy we can tap into.

The Population Bomb and the Green Revolution

Greater food production allowed larger populations with higher population densities. Greater productivity of fields meant that not every person needed to be a farmer, freeing up some of the population to specialize in other tasks. Larger populations, packed more densely, with more minds freed from the burden of growing food led to faster rates of innovation. Among those innovations were sanitation, vaccination, and penicillin. Those in turn dramatically reduced the impact of disease that had kept populations down. And so, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the world’s population boomed. And in 1968 Paul Ehrlich wrote The Population Bomb, arguing that the explosion of mouths to feed would imminently surpass the ability of mankind to grow more food.

While Ehrlich was writing that the battle to feed humanity had already been lost, it was in fact being vigorously fought. In Mexico, a young plant scientist named Norman Borlaug led an effort, funded by the Mexican government and the Rockefeller Foundation, to develop new strains of wheat that could be planted more often, that would produce more and bigger seeds, and that could resist common wheat diseases.

The results in Mexico were astounding. On similar-sized plots of land, Borlaug’s wheat varieties produced three times as much grain as conventional breeds, and they could be planted twice a year. By 1963, more than 90 percent of Mexico’s wheat crop was planted using Borlaug’s seeds. The total wheat harvest that year was an astounding six times what it had been in 1944, the year Borlaug started his work. Mexico was more than self-sufficient in wheat. It had become a wheat exporter. By 1967, Borlaug’s new wheat varieties were being planted around the world and had helped stave off forecasted famines in India, Pakistan, and Turkey.6 Three years later, the Nobel Committee awarded the unassuming, pickup-driving, one-room-schooled Borlaug the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts, which had saved the lives of billions.

Borlaug wasn’t the only one working on higher-yield crops in the 1960s. Inspired in part by his success and his methods, researchers in other parts of the world created disease-resistant, high-yield varieties of rice, corn, and other crops. Crop yields in the developing world more than tripled overall.

Of this remarkable progress William Gaud, director of USAID, noted, “These and other developments in the field of agriculture contain the makings of a new revolution. It is not a violent Red Revolution like that of the Soviets, nor is it a White Revolution like that of the Shah of Iran. I call it the Green Revolution.”7

Largely because of the Green Revolution, the massive famines predicted in the late 1960s never happened. Decade over decade, the fraction of humanity that is hungry has dropped since Ehrlich wrote The Population Bomb. In late 2011, world population crossed the seven billion mark, twice the number of people who were alive when The Population Bomb was written. Population has indeed exploded. And yet, around the world the amount of food available, per person, is at an all-time high. Population has increased by a factor of 2. Food supplies have increased faster, by a factor of almost 2.5.

Farming the Seas

The next frontier for farming is the world’s oceans. Today the majority of the fish humanity consumes isn’t farmed. It’s caught. That is to say, it’s hunted.

Hunting and farming have crucial differences. Where farmers focus on raising animals, ensuring their health, and the health of their herds, hunters focus on finding, catching, and bringing in animals. Both hunters and farmers care about how much food they can produce, of course, but how they go about it is different. A farmer who wants to produce more food works to grow his herd, increasing the population of the animals most consumed for food. A hunter who wants to produce more food works to increase the speed and efficiency with which he can take animals out of the world’s population.

Today, the species we hunt most aren’t deer or bears or wolves—they’re the fish in our oceans, rivers, and lakes. Tuna, snapper, cod, sole, bass, halibut, orange roughy, perch, and so many more. And it’s no coincidence that those species are all under pressure, with most of them at all-time low populations, and that yearly fishing catches have stalled even as an ever-larger fleet of ever-larger fishing boats make ever-longer trips to try to haul them in.

By comparison, the world’s population of cows, sheep, pigs, and chickens has never been higher.

The key to saving the fish in our oceans will be to transition from a culture of hunting fish to one of farming fish. That transition is underway now. Since 1990, the worldwide wild fish catch has been more or less flat at around ninety million tons of seafood per year. In that time, fish farms have grown from providing just over ten million tons per year to providing more than sixty million tons per year. For some species, like sea bass and salmon, fish farms now provide more food each year than wild-caught fish.8

Fish farms have come under attack for being environmentally unfriendly in other ways. In traditional open-cage fish farms, fish kept in high densities produce waste that washes out into the water and can potentially become a breeding ground for diseases and parasites that can spread to wild populations. In addition, farmed fish still need to eat, and much of what they consume is in the form of other, smaller fish. Fish farms consume those in vast quantities. Those are all legitimate criticisms.

Those problems are surmountable, though. New fish farming techniques use separated pools, where fish can be grown away from wild populations. The water in these pools is gradually recycled, allowing waste products and parasites to be caught and filtered out. And fish farms around the world are now experimenting with soy-based fish feeds and other types of feeds that reduce the need to consume large amounts of smaller fish. New ideas are addressing the environmental problems that fish farms create, while leaving in place their main advantage: a potential conservation of wild fish populations.

New ideas and new technologies are employed in wild fish hunting as well, of course. Bigger boats, larger nets, new ways of locating fish. But the main effect of these is opposite to the effect of new technology in fish farms. New developments in ocean fishing accelerate the rate at which fisheries harm the environment. New developments in fish farming reduce the harms.

Fish farms could be good for more than the health of our oceans. They’re also a more efficient way to turn vegetables into meat. It takes ten to twenty pounds of feed to create a pound of beef. By contrast, it takes just around two pounds of feed to create a pound of salmon. As we bring the agricultural revolution to fishing, we have the potential to both shrink our impact on wild fish and increase the efficiency with which we turn land into protein.

The Ever-Shrinking Footprint

Before agriculture, a square mile (2.6 square kilometers) could feed roughly a quarter of a person. Today a square mile of cropland producing average yields feeds almost 1,300 people. The productivity of farms in the developed world is roughly twice that of the world average, feeding a stunning 2,600 people. Our innovation in farming technology has multiplied the value of a plot of land by nearly 10,000.9

The converse of this is that by increasing the amount of food that a plot of land produces, we’ve reduced the amount of agricultural land needed. We’ve shrunk the “land for food” footprint of a single person by a factor of nearly 10,000 over the course of human history.

And here we diverge from the expectations of the IPAT equation. Because if Impact (the amount of land we use, for instance) = Population × Affluence × Technology, then we should expect to see far more land used for agriculture now, given that our population, affluence, and technology are all at all-time highs. Yet, on a global basis, the amount of land we use to grow food is only slightly higher than it was a thousand years ago. And on a per person basis, it’s dramatically less.

Our population is higher. Our affluence is higher. Our technology is higher. And that is the key. The “technology” term in the IPAT equation is working in a direction opposite the one expected by Ehrlich and others. Better agricultural technology is working to reduce the land-use impact of each person. Innovation and the accumulation of knowledge are substituting for land, a physical resource.

Figure 7.1. Persons fed by one acre of land. Agricultural innovations have increased the number of people fed by the same amount of land drastically and continually through human history. Data compiled from Marcus J. Hamilton, Bruce T. Milne, Robert S. Walker, and James H. Brown; B. H. Slicher Van Bath; and Food and Agriculture Organization.

Our Planet’s Rising Carrying Capacity

That also means that the carrying capacity of the planet has been increased. The carrying capacity of the planet using the farming techniques of 1900 was perhaps two billion people: five billion people fewer than it is today. The carrying capacity of the planet when we were hunter gatherers was around a thousand times less than it is today—in single-digit millions. There was simply no way, in those times, to produce enough food to feed the number of people who are alive today. Yet now there is. Carrying capacity isn’t fixed, it seems. The answer to the question “How many people can the planet support?” isn’t a constant. It depends on both their behavior (how much those people consume) and on the effectiveness and efficiency of the technology they use to tap into the resources they need—an effectiveness and efficiency that’s risen continually with time and innovation. Our technology is a physical manifestation of our knowledge base. As we’ve innovated and improved on that knowledge base, our technology has reduced the amount of land we need to feed a person, and thus increased the carrying capacity of the planet.

Reducing the land needed to grow food has other positive impacts. Agriculture is the number one cause of deforestation, accounting for about half of all tropical forest acreage cut down.10 To feed the number of mouths on the planet today at the yields we knew in the 1960s, we would have had to cut down roughly half the remaining forests of the world, with disastrous impacts for climate, the water cycle, and biodiversity. The green revolution, with its pesticides, its chemical fertilizer, its massive irrigation, and its mechanization has been the greatest savior of the world’s forests. Growing more food per acre leaves more land for nature.

The trend, then, is toward increasing the amount of food we can grow per acre, increasing the amount of food we can grow per gallon of water, increasing the amount of food we can grow per watt of power. We’re far from done with the Green Revolution. Even now, innovations in labs point the way to potential grain yields that are double today’s yields, to crops that can survive droughts or floods, to crops that are more efficient in their use of fertilizer and water, and more. Ten thousand years of innovating in agriculture suggest that at least some of these new ideas will bear proverbial—and actual—fruit, boosting the amount of food we can grow further.

How far could these trends go? There’s no practical limit in sight. Today the average yields in rich countries like the United States, Canada, Europe, Japan, and Australia are around twice the overall average of the world. Lifting yields in the rest of the world to developed-world levels would, by itself, double the amount of food production, meeting or exceeding the demand expected in 2050. The additional energy required to do so, in fertilizer, fuel, equipment, and so on, would be around 3 percent of the world’s total. If we can address energy concerns, we can lift yields.

Even that is far short of what’s allowed by the laws of physics, chemistry, and biology. The majority of the energy in food, even in the heavily mechanized agriculture of developed nations, is that provided by the sun. Yet an acre of corn or wheat in the United States, where yields are high, captures only around a tenth of a percent of the solar energy that strikes it. Photosynthesis, in principle, can capture as much as 13 percent of the energy that strikes a plant. That means that, in theory, on the same land we could be growing a hundred times as much food as we are today.

We already know how to achieve some of that gain. For example, plant scientists at the University of Florida’s Protected Agriculture Project have already shown that they can boost crop yields of many vegetables by a factor of 10 by growing them in low-cost plastic greenhouses.11 Purdue University scientists have shown that they can double the yield of corn by growing it in passive greenhouses, and nearly triple yields by growing corn underground with artificial lights. Even in traditional open fields above ground, the farmers who win the Iowa Master Farming contest each year typically get twice the average yields of the United States as a whole.12 There’s plenty of headroom to boost food production further.

Solutions, Problems, Solutions

This is not to say that modern agriculture has no negative impacts. Cows excrete methane that warms the planet. The energy used to run farm equipment and to manufacture fertilizer produces carbon dioxide that further warms the planet. Together the two produce around 18 percent of the warming effect created by humans. Nitrogen fertilizer runs off of soil and creates ocean dead zones where fish don’t live. Modern farming uses water drawn from aquifers and rivers. Pesticides used to protect crops from disease, weeds, and insects kill other plants and animals and spread into water supplies.

As is often the case, the solutions to one problem have created new problems of their own. To be sure, the new problems are smaller than the old. Had we not boosted yields through the Green Revolution, we would either have had billions starving or would have been forced to chop down the world’s remaining forests to feed the world. Either of those would be a worse result than the side effects we face now. That doesn’t mean that the problems of agriculture aren’t real, though. All things being equal, we’d like to feed the world and eliminate the problems of ocean dead zones, freshwater depletion, and CO2 emissions from the energy that agriculture uses.

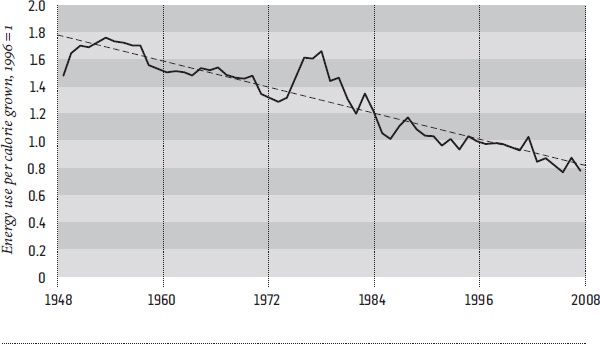

There are certainly signs that this is possible. While the total input of water and of energy into agriculture have increased, they’ve increased less than the amount of food we’ve produced has. According to the USDA, over the last several decades, advances in farming technology have cut the amount of energy used per calorie of farm output in the United Sates roughly in half.13 A bushel of wheat or corn or tomatoes grown today takes half the energy of a bushel grown in the 1950s. That energy figure includes the energy used to create nitrogen fertilizer, to create pesticides, to pump water for irrigation, and to operate mechanical farm equipment.

The Green Revolution didn’t result in the use of more energy for farming. The sharp rise in population increased the amount of energy needed (by increasing the amount of food needed). The Green Revolution advances in crop breeds, pesticides, fertilizer, irrigation, and farming techniques reduced the amount of water, energy, and land needed for every calorie of food we grow.

Figure 7.2. Energy use per unit of farm output. Farms in the United States use half the energy (in fertilizer, pesticides, farm equipment, and other inputs) as they did in 1948, per unit of food produced. Data from United States Department of Agriculture.

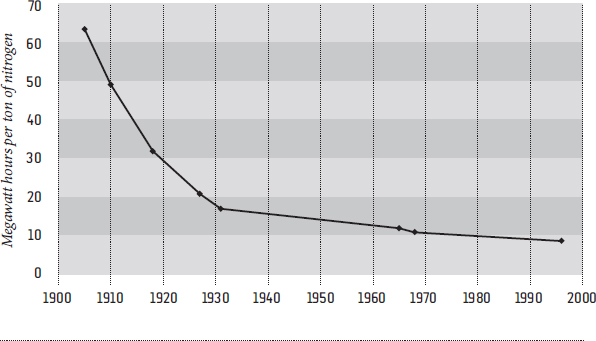

Most of this is a result of better crop yields from more advanced strains. Part of this, though, is the result of more efficient ways of creating nitrogen fertilizer. Creating fertilizer today takes roughly an eighth of the energy required when the first chemical fertilizer process was created in the early 1900s, and roughly a third less energy than the processes used in the 1960s.14

We’ve also become more efficient in our use of water to grow food. While the amount of water we use in farming has risen over the course of the last half-century, it’s risen slower than population and slower than farm output. In 2003, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN estimated that agricultural water use per capita shrank by roughly half in the forty years between 1961 and 2001.15 Water productivity, as it’s called, has continued to rise since then. In the twenty years between 1988 and 2008, for example, average irrigation per acre of U.S. cornfields dropped by 23 percent, while the amount of corn raised per acre increased by around 50 percent. The amount of corn raised in the United States per unit of water used nearly doubled in those twenty years alone.16 In the sixteen years between 1985 and 2001, the water efficiency of growing rice in Australia improved just as much. Australian farmers in the Murrumbidgee Valley used just over 2 million liters (around 530,000 gallons) to grow a ton of rice in 1985. By 2001, rising rice yields and more efficient irrigation had reduced that to just over 1 million liters (around 265,000 gallons) per ton of rice.17

Figure 7.3. Energy needed to produce nitrogen fertilizer. Synthesizing nitrogen fertilizer takes one-eighth the energy it did in 1900.

Data from Jeremy Woods et al.

Similarly, the total amount of insecticide used in the United States has dropped by a factor of 3 over the past few decades. And while herbicide use has remained roughly flat, use of the herbicides the EPA classifies as most toxic has dropped by a factor of 10, and concentrations of those herbicides in rivers in the U.S. Midwest have dropped by a factor of 30.18

None of this is to say that agriculture’s problems have been completely solved. They haven’t. But over the last few decades, innovation has reduced the amount of energy, water, insecticide, and most dangerous herbicides necessary to feed one person. With the right incentives, right rules, and right innovation in new technologies, there’s no reason to believe that we can’t fix those problems. They won’t fix themselves. They’ll require, at minimum, that we give farmers a reason to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and runoffs of pesticides and nitrogen. But if we decide, collectively, to do that, then the technology can be developed to make it happen.

More than 10,000 years ago, we started the transition from hunting wild animals and foraging for wild vegetables to intentionally growing and raising the food we want. Now we’re on the verge of transforming seafood to that model. And at the same time, further innovation in farming on land can increase food yields further, while reducing the environmental damage of farms.

Agriculture is an amazing example of the power of ideas to multiply our resources. In the span of 10,000 years we’ve multiplied the amount of food energy we can extract from an acre of land by a factor of 10,000. Our continual process of innovation, of devising new ways to put matter and energy together—has multiplied the value of the finite amount of land we have again and again and again. It continues to today. And, as we’re about to see, the right knowledge has multiplied the value of nearly every other resource we’ve ever encountered. The most valuable resource we have isn’t energy or minerals or land. It’s our ever-increasing store of ways to put those physical things together in new and more inventive forms that give us greater and greater value.